The Drowned and the Saved

War & Peace | Week 45 | Contains spoilers up to Volume 4 Book 3 Chapter 18

Listen to this section:

1. First thoughts

This week, Tolstoy reminds us again that characters do not exist to please us, or entertain. We are not their judge but an imperfect friend, struggling to understand.

Because: how hard it is to imagine Pierre’s suffering. I’d put myself in his shoes, but those happy feet are bare and bleeding now. As the transport moves west, two-thirds of his fellow prisoners melt like snow or are shot on the roadside. Lice cover his body, horseflesh on his tongue, seasoned with gunpowder.

But here on this road of misery, he thinks, “there is nothing in the world that is terrible.”

He is stoical: with the right state of mind, one can endure the pains of this world, and even find comfort and beauty in them.

Meanwhile, his friend and mentor is falling. He has given up. He puts his fate in God and, without grumbling, hopes for death.

Pierre hardly notices. Worse, “his feeling of pity for this man frightened him,” and he does not look back when the bullet comes.

If this seems callous or self-absorbed, perhaps it is. But Pierre is in survival mode, and Platon’s despair and fatalism are infectious. And his story of a merchant’s exile is his way of saying goodbye.

But Pierre loves life. So he buries himself deep in memories and hardens himself to the pain all around.

As with Andrei and his father, the story helps us understand the good place from where stems indifference and even cruelty. How the world’s worries and a Russian winter may make our heads and hearts go numb.

Poor Platon of the magic potatoes. His death and Pierre’s survival remind me of the words of Primo Levi in the last book he wrote: The Drowned and the Saved.

He survived Auschwitz but could not survive the guilt:

“The prisoners who saved themselves were not the best.” They were “the selfish, the violent, the insensitive.”

Pierre and Primo are not “bearers of a message” from the abyss. They are poor witnesses, averting their gaze. It is Platon’s story that tells us what it is like to reach the end of the road, not Pierre’s.

Pierre survived the worst. But, as Primo Levi wrote, “the best are all dead.”

2. Character cheat sheet

There are a few French marshals of the empire mentioned this week. So let’s put some faces to names…

Jean-Andoche Junot

Pierre is no longer with the cavalrymen who escorted the prisoners out of Moscow. His column includes the “Marshal Junot’s enormous baggage-train.” Curiously, it looks like Tolstoy has made a mistake here: Jean-Andoche Junot was not actually a marshal. The Burgundian revolutionary was nicknamed “the tempest” and commanded the 8th Corps at the battles of Smolensk and Borodino.

But Napoleon wasn’t pleased with his performance, complaining, "Junot has let the Russians escape. He is losing the campaign for me.” Probably for this reason, he was never given the prestigious baton of Marshal of the Empire.

Marshal Berthier

In chapter 16, Louis-Alexandre Berthier sends a letter to the emperor informing him of the desperate state of the army. Historians remember him as an efficient administrator who opposed the rapid advance towards Moscow. When Napoleon ignored his prescient warnings, he reportedly burst into tears. He retired shortly after the campaign and, in 1815, fell from a window to his death in unexplained circumstances.

Marshal Ney

Michel Ney had the unenviable command of the rearguard as the Grande Armée retreated through Russia. He was known as "the last Frenchman on Russian soil" for leading the rearguard across the Niemen on 14 December. Napoleon called him “the bravest of the brave”, and here he is, patriotically presented by the French painter Adolphe Yvon:

3. Discussion Questions

What is the significance of Platon’s story of the merchant wrongly accused of murder?

Do you agree with Pierre’s conclusion that “there is nothing in the world that is terrible”? What does he mean?

Is Pierre relatable in these chapters? Is he sympathetic?

4. Join the discussion

Let me know your thoughts in the comments. You can also connect with other readers in the group chat on Instagram and the Discord server. Let me know if you want to be added to either of these.

5. Choose your own adventure

Thank you for reading this War and Peace update. Below, there is bonus content for paid subscribers. These readers keep this show on the road, and I couldn’t do this without them.

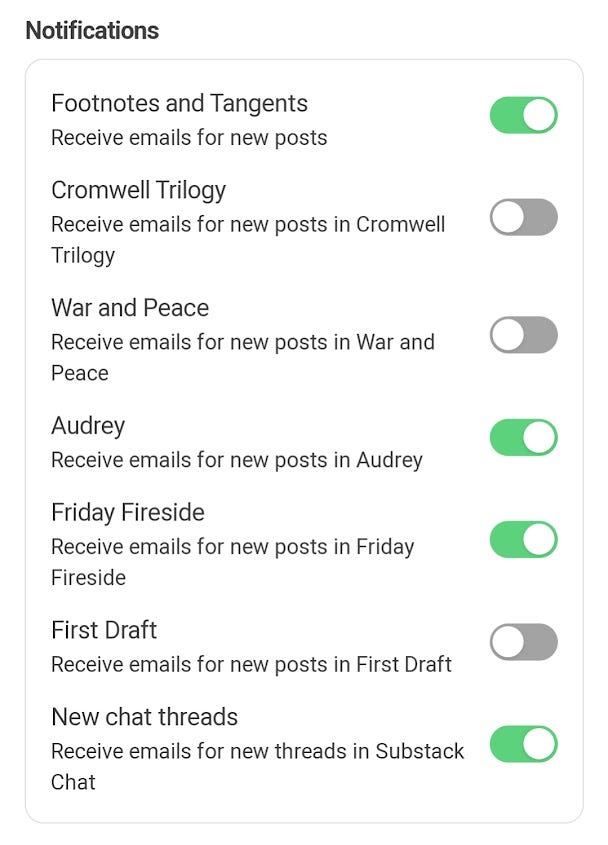

Remember, you can pick and mix which of my letters you want to receive by turning on and off notifications on your manage subscription page. The default settings look like this:

6. Bonus notes and discussion

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.