Hi, Simon here. If you’ve recently signed up to read War and Peace in 2024, read no further! This is the tail end of the 2023 reading and is wall-to-wall spoilers!

Welcome to week 47 of the War and Peace read along, a chapter a day. This is a Footnotes and Tangents newsletter for our community of slow readers. It is free for all, with bonus material for paying subscribers. Enjoy!

Listen to this section:

1. First thoughts, a tangent

The stars, as if knowing that no one was looking at them, began to disport themselves in the dark sky: now flaring up, now vanishing, now trembling, they were busy whispering something gladsome and mysterious to one another.

What fools we have been. We who call ourselves human.

We wonder why we're born. Why we suffer so and make others suffer more. Why we struggle and we fight. Why we're always wanting more. Why we wonder, always wondering: What for? What for?

What fools we have been, wanting more.

We readers need heroes, and villains to despise. Judgement and redemption. A story that arcs to justice. A tale with a beginning and an end.

This is not that kind of story.

In 1812 and 2023, men will go to war. Forgetting who and what they are, they'll make up names for countries. And ideas that smell like gunpowder. They'll make monsters of their neighbours and fight devils in their sleep.

And nobody dare whisper: What for? What for?

Every night, the same stars shine. That trembled over Moses and Mohammad, and that whispered to the first men, and women walking upright, hands holding tools, and heads tilted to the sky.

The lofty sky. An infinite abyss, cradling us in our troubles as we wander down below.

Each of us, so different. So legitimately peculiar. Messed up and all so broken, in our own very special way.

I am you and not you. 13.7 billion years. Of stardust and starlight colliding to make children of the dust. Dust that dared to think. And ask the silly question: What for?

Pierre Bezukhov, you holy fool. You seeker. Short-sighted in your spectacles, scrutinising sacred texts for meaning that isn't there. You fool, Pierre. The answers were always straight in front of you. They were always at your feet.

We are stardust, we are human. We are wonderfully complete. The stage-coach driver, the post-house overseer, the peasants on the road. Everyone you meet. In this book and in life.

Be still and listen gently now. To each and every one. There is an answer to the question. What for? What for?

2. The People of War and Peace

Matvei Platov

They say Platov took ‘Poleon himself twice. But he didn’t know the right charm. He catches him and he catches him again—no good! In his hands there’s nothing but a bird who spreads his wings and flies away.

Oh, I love this little anecdote about Napoleon turning into a bird. Platov commanded the Don Cossacks as they chased the remnants of the Grande Armée out of Russia. He later visited London, where he was awarded a golden sword and an honorary degree from the University of Oxford.

Captain Ramballe

13th Light Regiment, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor:

Oh, you fine fellows, my kind, kind freinds! These are men!

We last saw Ramballe in Moscow, on a night of friendship and dissipation with one Pierre Bezukhov. The night, the city began to burn. A romantic who is quick to love and forgive, he is one of the 26,500 French prisoners taken at the Battle of Krasnoi.

Morel

It’s good to see Ramballe again, even if he is so much worse for wear. And the clemency and comradeship between the Russians and French contrast with the horrors we have witnessed up until now. But the social divisions remain rigid: the French officer has the comfort of the hut. His drunk orderly joins the soldiers in the cold night.

The Russians cannot understand Morel, but they get him nevertheless. They are all just men together under the same stars. He sings, Vive Henri Quartre:

Mikhail Kutuzov

This week, the French crossed the Berezina River and finally left Russian territory. As far as Field Marshall Kutuvoz was concerned, this was mission accomplished. His emperor had other ideas. Viewing himself as the saviour of Europe from the anti-Christ Napoleon, he intends to continue the war beyond Russia. The old general is given a new title and a medal, and then he is quietly retired. Tolstoy concludes:

Kutuzov did not understand what Europe, the balance of power, or Napoleon, meant. He could not understand it. For the representative of the Russian people, after the enemy had been destroyed and Russia had been liberated and raised to the summit of her glory, there was nothing left to do as a Russian. Nothing remained for the representative of the national war but death. And so he died.

In the Soviet era, Kutuzov was venerated as a national hero. There are at least ten towns named Kutuzovo. In 1943, the Red Army launched Operation Kutuzov, a counteroffensive against Nazi Germany. The Order of Kutuzov remains the second-highest military award of the Russian army.

At least 24 ships around the world have been named after him, and at least one plane, owned by Aeroflot. In Ukraine, a monument to Kutuzov was demolished in 2014, and streets in Kyiv bearing his name have been renamed.

Pavel Chichagov

One of the most zealous ‘cutters-off’ and ‘breakers-up’.

The Russian general meets Kutuzov as Vilna and hands him the keys to the town. He is “contemptuously respectful” of the old field marshall, knowing that Kutuzov’s day is done. But the emperor isn’t pleased with Chichagov either. Pavel Chichagov has been trying to do what Kutuzov and – with hindsight – Tolstoy believe is impossible: to capture Napoleon. Alexander blamed him for Napoleon’s escape at Berezina and dismissed him the next year.

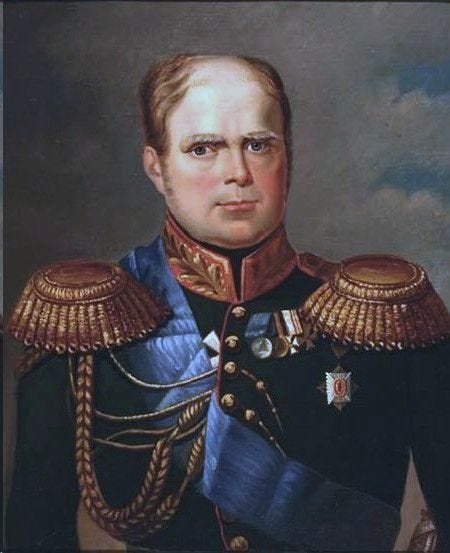

Grand Duke Tsarevich Constantine

Constantine is Alexander’s younger brother and heir-apparent. We haven’t seen much of him since the disastrous Austrian campaign at the beginning of the novel. Well, here he is, arriving at the end of our story to tell Kutuzov of “the emperor’s displeasure”.

After the war, Constantine became Governor of Poland and settled there, secretly renouncing his claim to the Imperial throne. In 1825, his refusal to succeed his brother as Tsar led to the Decembrist revolt.

Tolstoy’s original intention was to tell the story of a participant in this uprising, who is exiled to Siberia and later returns. All that remains of that character is his name: Pyotr. Pierre.

Pierre Bezukhov

A joyous feeling of freedom—that complete inalienable freedom natural to man which he had first experienced at the first halt outside Moscow—filled Pierre’s soul during his convalescence.

It may seem strange that Pierre is happy. He has learned of the deaths of his wife, his friend and his namesake, Petya. We, poor readers, have endured each of these deaths and are feeling fairly miserable about all of it. So it is easy to reproach Pierre here and feel upset, as though he won’t partake in our grief.

But Pierre has been on this long journey of fire and ice, the firing squad and the Smolensk road. On that journey, he lost everything but the one thing that could not be taken away from him. Remember that night outside Moscow:

Pierre glanced up at the sky and the twinkling stars in its far-away depths. ‘And all that is me, all that is within me, and it is all I!’ thought Pierre. ‘And they caught all that and put it into a shed boarded up with planks!"‘

They couldn’t capture his “immortal soul” or, as he later reasons, the source of our “full strength of life”:

the saving power he has of transferring his attention from one thing to another, which is like the safety value of a boiler that allows superfluous steam to blow off when the pressure exceeds a certain limit.

It is this strength of controlling his attention that allows him to survive his ordeals since the burning of Moscow. This makes him seem detached and distant, and as foolish as before. But it also frees him to focus on others. And he now becomes wonderfully curious about those around him. And maybe, for the first time in the novel, he truly listens to others.

Count Willarski

A Polish count who sponsored Pierre’s admission to the Brotherhood of Freemasons in 1807. Willarski is what Pierre might have become: a bored official who regards his family life as a hindrance to his masonic interests. Pierre has since abandoned Freemasonry, and they really have very little in common.

But despite himself, Willarski finds he quite enjoys Pierre’s company. Why? Because Pierre is a good listener, good company and full of nonjudgmental curiosity of others:

This legitimate pecularity of each individual, which used to excite and irritate Pierre, now became a basis of the sympathy he felt for, and the interest he took in, other people.

Willarski is still looking past and through people in search of mysterious truths. Pierre has found those truths in people. In Willarski, in the princess, the doctor, the stage-coach driver, the post-house overseers, and the peasants on the roads and in the villages.

3. Questions to think about

Is Kutuzov the hero of War and Peace? If not, why not?

Pierre believes it is impossible to change a man’s convictions by words. Do you agree? Do you think Tolstoy agrees with Pierre?

How are Marya, Natasha and Pierre’s experiences of grief different and similar?

4. Join the discussion

Let me know your thoughts in the comments. You can also connect with other readers in the group chat on Instagram and the Discord server. Let me know if you want to be added to either of these.

5. Choose your own adventure

Remember, you can pick and mix which of my letters you want to receive by turning on and off notifications on your manage subscription page. The default settings look like this:

6. Bonus notes and discussion

You are reading a War and Peace update. Below, there is bonus content for paying subscribers. These readers keep this show on the road and allow me to keep most of this read-along free for all.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.