Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 10, 12, 12 & 13

The first sepoy assault on the Residency finds the Collector asleep and the Padre in an evangelical mood. He tours the defences, handing out devotional tracts. At the banqueting hall battery, Fleury and Harry decide whether it is sporting to shoot at any native they can see.

The attack comes before they have a chance to fire. Most of their men are killed, and they send a message to the Collector for reinforcements. Fleury gathers wool, and Major Hogan gets shot. The Collector sends his manservant, Vokins.

Meanwhile, the Collector conducts his own tour of the Residency, his cheerful pink rose whithering in his buttonhole. Harry prepares the men and the cannon, and the Padre gets to work on Fleury’s damned soul. Against the odds, they survive an infantry charge.

Time passes. The Collector goes about his duties, visiting the women in the billiard room and discussing the mutiny and civilisation with the Magistrate in the record room. Fleury tries to get a word in, but they both agree he is talking ‘gibberish.’ The Collector and Fleury visit the hospital, where Doctors Dunstaple and McNab are engaged in a battle of treatments as an English private sings about Crimea.

Footnotes

1. The cities of the plain

If they now found themselves in mortal danger it could only be that God was displeased with them and was preparing to punish them as he had punished the Cities of the Plain!

These are five cities mentioned in Genesis: Sodom, Gomorrah, Zoara, Admah and Zeboim. God destroys four of these cities, saving Zoara for Lot and his daughters. Sodom and Gomorrah became a byword for destruction, explained as God’s vengeance for moral wickedness.

2. Sin is hydra-headed

But Sin is hydra-headed; chop a sin off here and a dozen more are bristling in its place.

The Hydra of Lerna was the many-headed monster of the lake of Lerna, guarding an entrance to the Underworld. For every head chopped off, two would grow in its place. It was killed by Hercules. The Padre has taken on the Herculean task of ridding his Krishnapur flock of their sins. It is an impossible task. If God is punishing the British, it may well be for other sins than the ones Padre sees.

3. Kabul grapes

Barlow, the taciturn man from the Salt Agency, who had spent the early hours eating Kabul grapes and dismally spitting the pips into a handkerchief which he afterwards replaced in his pocket, sat in a chair with his hands in his pockets breathing asthmatically.

These are probably preserved grapes from Afghanistan prepared in a kangina (an Eastern Persian word meaning ‘treasure’). The fruit is sealed into a mud disc that absorbs moisture and allows air to keep the grapes fresh for up to six months.

Later in the chapter, Fleury steps on one of these grapes and recoils, thinking he’s stepped on an eyeball. A wonderful use of the imagination to distil horror on the page. Tangentially, in Pat Barker’s Regeneration Trilogy, Billy Prior is traumatised by memories of holding a comrade’s detached eyeball in the trenches of the First World War.

Footnote: The ancient method that keeps Afghanistan’s grapes fresh all winter. (Atlas Obscura)

4. Protection of the philosophers

But now the giant heads of Plato and Socrates, each with an expression of penetrating wisdom carved on his white features, surveyed the river and the melon beds beyond.

Stones are on the move. The Padre bemoans the ‘sinful’ stone jars that have taken the place of the congregation in his church. At the Banqueting Hall, the marble busts of Plato and Socrates are ‘a concrete symbol’ of European civilisation. They now act as sentinels, guarding Harry and Fleury’s fetishised six-pounder.

Our besieged characters consider their situation philosophically with recourse to the reassuring alchemy of mathematics. Sins increase ‘daily as by a system of compound interest.’ And the dilemma of which sepoys one can kill is resolved according to the angle of their ‘mischievous’ intentions.

5. The Redan at Sebastopol

Without their British officers, of course, the sepoys were likely to commit the most extraordinary follies, such as attacking impregnable positions (never mind for the moment the Redan at Sebastopol.)

It was true that the sepoys lacked leaders with professional experience in strategy and tactics – Indians were precluded from promotion to higher ranks. However, Farrell points out that the British were perfectly capable of their own strategic blunders.

The Great Redan was a fortification defending the city of Sebastopol during the Crimean War. Thousands were killed or wounded in the British piecemeal assault on the Redan; casualties that could have been avoided had the city been taken decisively from the south much earlier.

The British press and government blamed the disaster on Field Marshal Reglan, who died a few months later from dysentery. The British and French lost over 100,000 lives in the siege, mostly to disease.

6. Fleury in the line of fire

Had not Lamartine been a military man? With French poets you could never tell. He stepped back, his ears ringing as the cannon crashed again. He could not remember.

‘Almost everybody appears to be dead,’ is Fleury's dismal summary of the first unexpected assault on the banqueting hall. You’d think it would make him sit up and pay attention. But while they load the cannon, he has begun to compose ‘an epic poem’, while considering human nature and the military experience of his favourite poets.

Alphonse de Lamartine had indeed been a military man. He avoided recruitment into Napoleon’s Grande Armée and the disastrous Russian campaign, taking an administrative position in the army. He fled to Switzerland during Napeolon’s Hundred Days in 1815.

Lamartine was a prominent figure in French Romanticism. As well as his poetry, he wrote Voyage en Orient, a travel journal of the Middle East and South East Europe.

In 1848, he stood for election in the first French presidential elections, losing to Napoleon’s nephew, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte – later Napoleon III, the last French monarch.

'Fleury, for God's sake!'

Our protagonist has been distracted by the footnotes and tangents, too busy penning captions for the Illustrated London News to save his own skin.

7. Pariah dogs

The humans he had got used to, in time … the dogs never.

Chapter 11 is a brilliant sketch of the Collector’s little walk around the besieged compound. He attempts to put on a calm and confident demeanour to boost morale, but the cheerful pink rose in his buttonhole withers within minutes of exposure to the hot wind and sun.

Like the British and Indians, the burdensome pets are separated from the ‘uncivilised’ pariah dogs, which the Collector compares to the ‘human beggars’ beyond redemption at Garden Reach in Calcutta.

Garden Reach is a neighbourhood in Kolkata on the banks of the Hooghly River. Tangentially, it was the refuge of the last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, until he was imprisoned with his Prime Minister (like Hari) to prevent him from joining the Indian Rebellion.

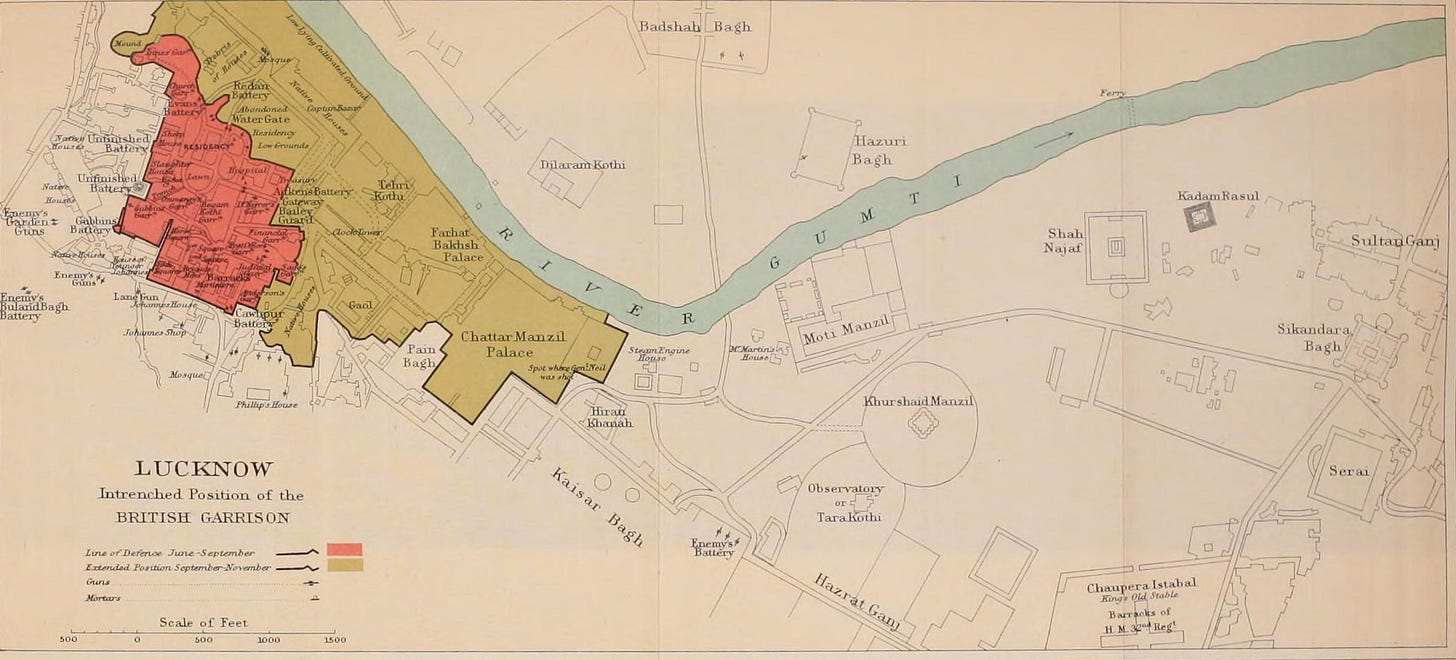

Prior to being deposed by the East India Company, Wajid Ali Shah built the magnificent Qaisar Bagh palace at Lucknow, which became a stronghold for rebels during the uprising and was later looted by drunken British soldiers.

The last Nawab of Awadh was a major patron of the arts and an enthusiast for Hindu culture. He modelled himself on Lord Krishna.

Krishnapur! Even the name of their community was that of a heathen deity.

8. The Watchmaker

'If you believe, as you must, that God designed the world and everything in it, then why should you not proclaim it? Why should you not praise Him for these wonders He has created? I'm sure you read Paley at school.'

The Padre is talking about William Paley, the Christian philosopher and author of Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity (1802). Paley introduced the watchmaker analogy, an argument for the intelligent design of the Universe.

The Padre uses ‘eel’s eyes’ to bolster his point. This makes me think of the Kabul grape that Fleury mistakes for an eye, and Harry squinting at sepoys trying to judge distance. Padre and Paley’s theories are based on a misapprehension of evolutionary forces, another example of the failure to see things for what they are.

‘God has nothing to do with that sort of thing,’ Fleury objects. But the two men have one thing in common: the existential threat posed by the sepoys provokes in them impractical trains of thought. It is the dim and dull Harry who seems best prepared to survive the sepoy assault.

Fleury stared at the Padre, too harrowed and exhausted to speak. Could it not be, he wondered vaguely, trembling on the brink of an idea that would have made him famous, that somehow or other fish designed their own eyes?

9. Perfect strangers

It has never occured to him that either of the girls had a will which might in any circumstances wishh to oppose itself to his own.

The Collector considers his ‘real self’ as hidden from his daughters. But they, like Indians and Vokins (the British working class), are beyond his understanding. Class, gender, and empire – the Collector sees all and understands nothing. And to his irritation, it is his daughters who have the telescope.

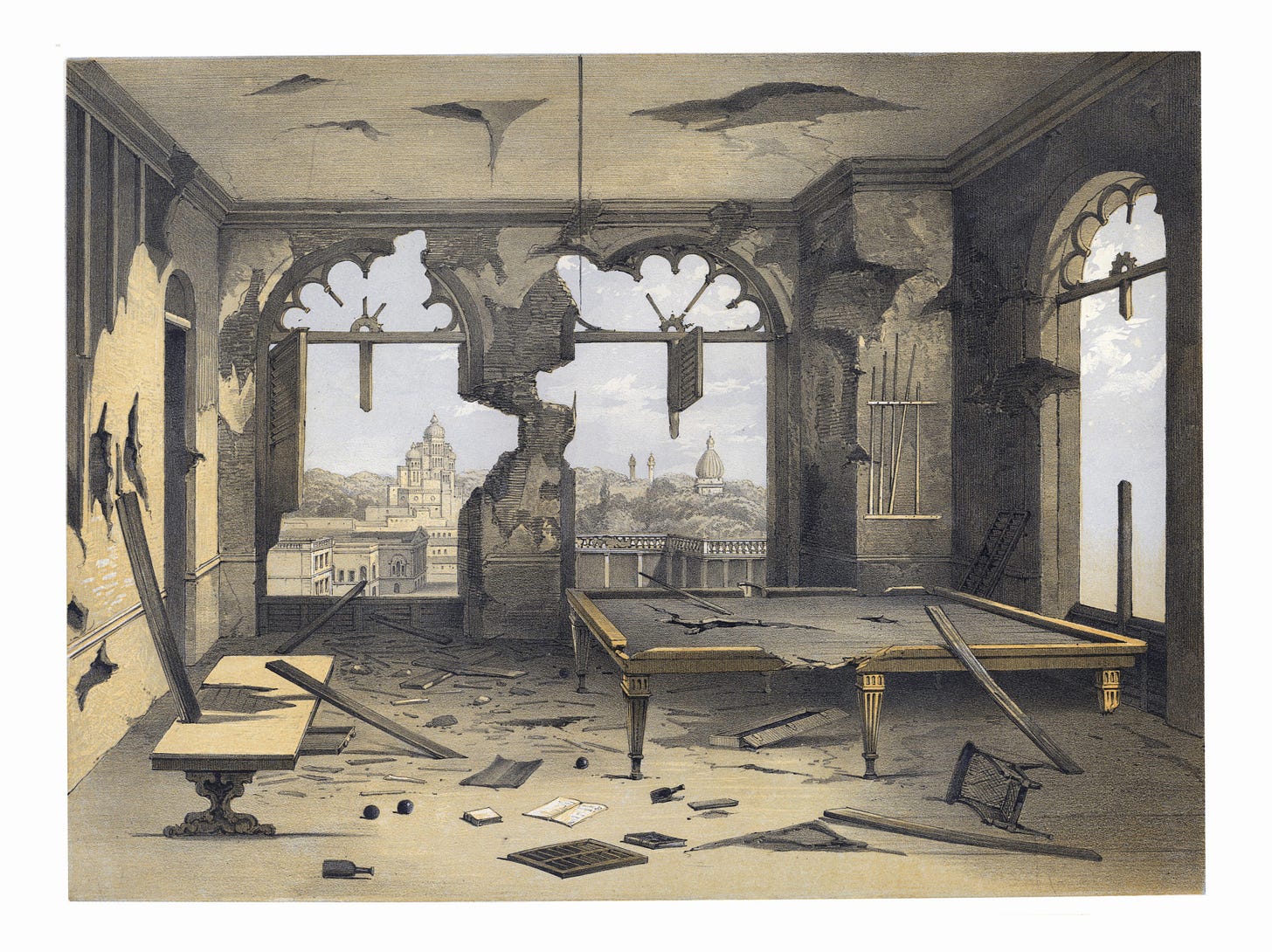

Is this story about dangerous incursions into the hallowed space reserved for Victorian men? Outside, Indians lay siege to the Residency. Inside, women have invaded the billiard room:

This room, so light, so airy, so nobly proportioned, had been utterly transformed by the invasion of the ladies.

In fact, the women have re-purposed this exclusive leisure space for living. The Collector muses that ‘women are weak, we shall always have to take care of them’, but it is he who seems buffeted by offensive sights and smells and his own inappropriate desires.

10. Congreve rockets

'One of the advantages of our civilisation,' said Fleury.

Congreve rockets were designed by the British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808. However, they were actually based on the Mysorean rocket used against the East India Company by the Kingdom of Mysore. The kingdom’s ruler, Tipu Sultan, was one of the company’s most formidable opponents until his death and the annexation of Mysore in 1799.

11. King Cholera

Cholera. The Collector could see Dr Dunstaple's anger swelling, as if himself infected by the mere sound of the three syllables.

In 1857, the world was in the final stages of the third and deadliest Cholera pandemic of the century. All six pandemics began in India, where they claimed more than 15 million lives between 1817 and 1860.

Doctor Dunstaple is administering calomel with opium and capsicum. Calomel is mercury chloride and was considered a panacea for disease treatment in the nineteenth century. American Founding Father Benjamin Rush introduced the ‘heroic dose’ of 20 grains taken four times a day to purge the body of sickness.

Calomel treatment resulted in mercury poisoning but was still used as a medicine in the early twentieth century. It was one of the ingredients in the ‘Number Nine Pill’ administered to soldiers in World War One.

Doctor McNab is ‘experimenting’ with mustard poultices, thought to draw out harmful toxins. This and other treatments lead Dunstaple to conclude that McNab is a ‘quack’.

Disease and medicine are recurring themes in the work of JG Farrell, who contracted polio while at university. The debates between the two doctors closely follow those of the time and are taken from primary source material. The link between medicine and empire was established early in the book when Fleury described civilisation as a ‘beneficial disease.’

And, of course, a Cholera outbreak would be catastrophic in the close confinement of the Krishnapur siege.

Footnote: ‘A Great Beneficial Disease’: Colonial Medicine and Imperial Authority in J.G. Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur.

Footnote: Mustard, medicine, and health (Lloyd Library)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will read Chapters 14–17 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

You asked for it! So here’s:

Cholera: the Origin Story

I’ve been amateurishly interested in infectious diseases for a long time and have taken every opportunity to incorporate that interest into my professional life as a teacher - classes about medical history are usually rather a big hit (eww, gross!). Pretty soon, I decided to give cholera the award as the most interesting pandemic-causing disease, because it has had such a fascinating impact on the way we live and is so closely linked with the progress, or lack thereof, of modern history. It hit the world at a time when medical science was just beginning to spread its wings, causing a large number of doctors and scientists to get into public rows about what caused it and how best to treat it.

The microbe behind the swift killer cholera is a strain of plucky little Vibrio cholerae, a bacterium that usually coexists peacefully with tiny copepods in the Sundarbans of Bengal. Sonia Shah, in her excellent book Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Coronaviruses and Beyond (2020) writes about the microbe’s home:

“This was a netherworld of land and sea long hostile to human penetration. Every day, the Bay of Bengal’s salty tides rushed over the Sundarbans’ low-lying mangrove forests and mudflats, pushing seawater as far as five hundred miles inland, creating temporary islands of high ground, called chars, that daily rose and vanished with the tides. Cyclones, poisonous snakes, crocodiles, Javan rhinoceros, wild buffalo, and even Bengal tigers stalked the swamps. The Mughal emperors who ruled the Indian subcontinent up until the seventeenth century prudently left the Sundarbans alone. Nineteenth-century commentators called it “a sort of drowned land, covered with jungle, smitten by malaria, and infested by wild beasts,” and possessed of an “evil fertility.” “ (p.18)

As long as Vibrio cholerae simply cleaned up the excess chitin left behind by the copepods, it was an innocuous enough little microbe, but then a certain turn of events offered it the chance to become a powerful zoonotic disease because of population pressure. And guess whose fault that was?

“But then, in the 1760s, the East India Company took over Bengal and with it the Sundarbans. English settlers, tiger hunters, and colonists streamed into the wetlands. They recruited thousands of locals to chop down the mangroves, build embankments, and plant rice. Within fifty years, nearly eight hundred square miles of Sundarbans forests had been razed. Over the course of the 1800s, human habitations would sprawl over 90 percent of the once untouched, impenetrable, and copepod-rich Sundarbans.” (p. 19)

Stay away from remote animal habitats, humans! It’s a terrible idea to encroach upon them! By offering to be a new host, you’ll give microbes ideas about evolving into something sinister! Plucky little cholera (I really respect its enterprising nature!) acquired a filament to its tail which allowed it to form large colonies, the better to colonize a human gut with. Even worse, it began to produce a toxin that would upset the human gut spectacularly - reversing the normal function of this organ to leach the body of all fluids, so that victims of a cholera infection would shed copious amounts of highly infectious rice-water diarrhoea and effectively dry up, wither and die within hours.

In the early 1800s, thanks in part to the British Empire, people had become much more mobile than before, and therefore plucky little cholera was able to hitch a ride to almost every corner of the earth within a few decades, causing the first pandemic in Bengal in 1817 and reaching Paris in 1832, where it caused a mad frenzy of cholera parties - immortalized via newspaper reports in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death.

In a way, it was the Sundarbans’ revenge for the brutal exploitation of Bengal and the rest of the Indian subcontinent. Except that these things are never intentional, just very predictable.

There’s much more! If anyone wants to hear about the extremely irrational behaviours the various cholera pandemics caused, the frenzied quest to find out what caused it (with a Soho doctor in a starring role as the Sherlock Holmes of cholera research) or the impact it had on cities like London, New York or my own Munich, you need only ask. I’m perfectly capable of tediously droning on for many more pages on the microbe of microbes - plucky little cholera!

Random thought that occurred to me - These chapters sum up why I prefer books to films. There is no way I could watch a film of all the death & suffering (I’m far too squeamish for all that blood) and if I did I wouldn’t be able to see the humour of the padre or the grape ‘eyeball’ but reading I can feel both the horror and the humour. Fascinating and I loved the tangents - especially the grapes in Afghanistan- strangely I found that the most fascinating of all.