Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 7, 8 & 9

On the roof of the Residency, the Collector and the Magistrate watch the refugees enter the enclave, bringing all the possessions they can carry. Fleury and Harry return from their adventure to stories of the ‘abattoir’ at Captainganj.

Night falls, and the abandoned bungalows begin to burn. The Collector leads preparations for the Residency’s defence, putting Harry and Fleury at the safest point: the battery at the banqueting hall. Fleury in his Tweedside lounging jacket feels out-of-place and unwanted.

In the Cutcherry1, the Collector and the Magistrate discuss the necessary destruction of the mosque, while Harry and Fleury go to ‘rescue’ the ‘fallen woman’, Lucy Hughes. She is in a suicidal frame of mind, and the two young men are ill-prepared to convince her of the joys of life.

Days pass without an attack from the sepoys. Native Christians are turned away from the Residency with certificates of loyalty. The General dies, and the Padre gives a fiery sermon to a near-empty church. The two young men go again to convince Lucy Hughes to come to the Residency but spend most of the time admiring her smooth skin and bare neck.

Fleury visits Louise and ends up arguing with the Padre while holding a non-sacrificial baby. The Padre gives the children sugar fruit to distribute among the unfortunate native Christians at the gate. Fleury talks of ‘a civilisation of the heart’ with Louise, who agrees to help bring Lucy to safety.

The sepoys empty the prisons and march off with the contents of the Treasury. Lucy arrives just in time, as the rest of the cantonment goes up in flames. The Collector admires his silver centrepiece at the Residency’s Last Supper, then goes to see Hari, held hostage to guarantee the Maharaja's neutrality. They ascend to the roof to see the cantonment burn.

‘That’s not a sight we see every day of the week.’

Footnotes

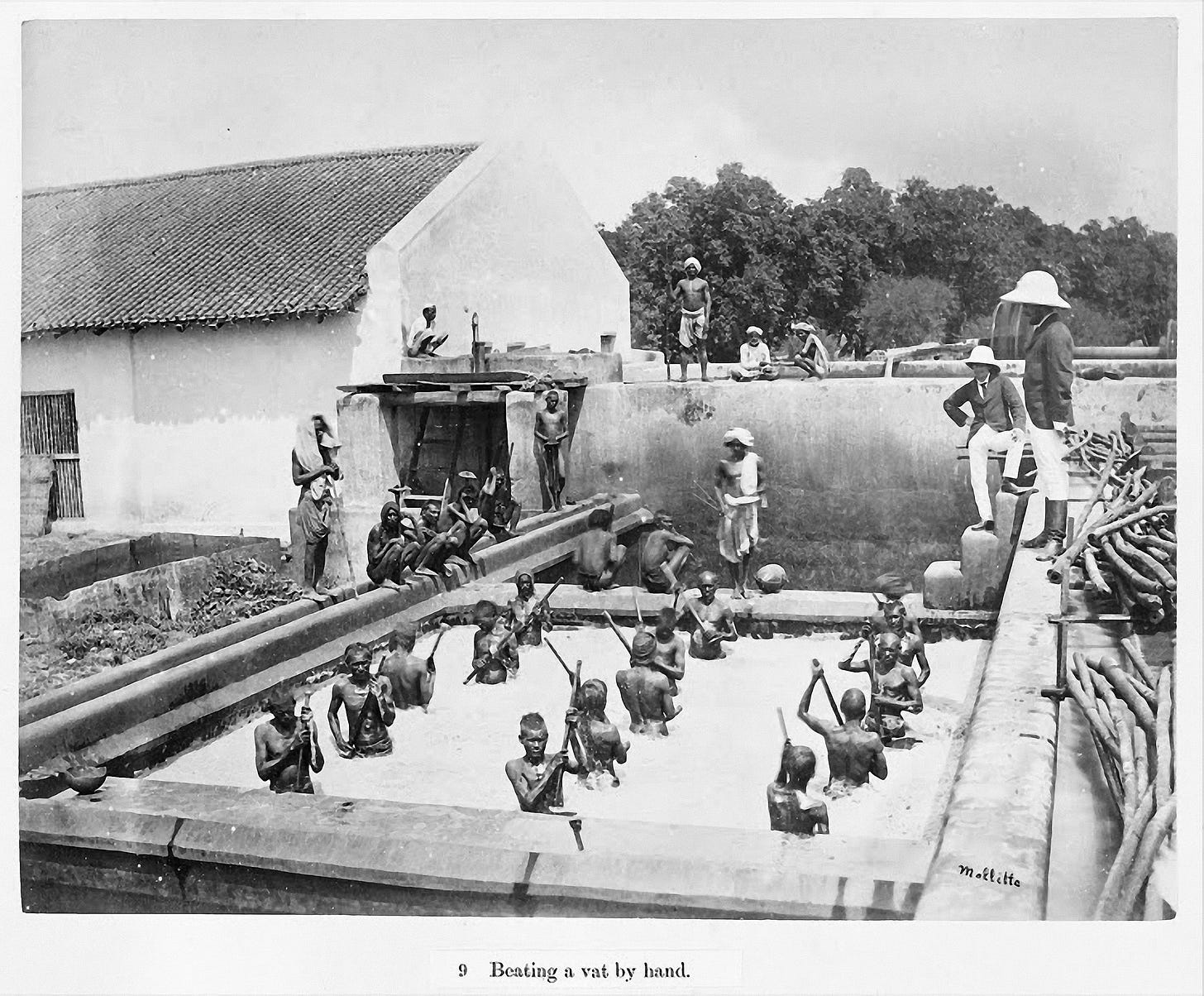

1. Blue gold

Harry and Fleury had spent the late afternoon riding about the country warning indigo planters to come into the Residency.

The story of this highly-valued dye is soaked in a dark colonial history. Indigo planting and manufacturing is a complex and skilled process, and West Africa was historically a centre of skilled indigo production.

Europeans enslaved these craftsmen on plantations in Haiti and Jamaica, generating enormous indigo wealth for French and British slave owners. Julien Raimond, an indigo planter in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, the first successful uprising against slavery in modern times.

Modern manufacture was brought to India by a Frenchman, Louis Bonnaud, in 1777. As with poppy production, the East India Company forced Indians to grow indigo instead of food crops. Shortly after the Indian Rebellion, peasants in Bengal revolted against the indigo planters.

Footnote: The story of India’s ‘blue gold’ (Al Jazeera)

Watch: A Short History of the Colour Indigo (National Gallery)

Tangent: Himalayan Indigo (Google Arts & Culture)

Tangent: Mary Oswald’s indigo dress (National Gallery)

2. Empire of things

Now, on the roof, all was quiet except for that laboured breathing, the crunching of gravel and the creaking of wheels, that filtered up from the struggling mass in the darkness below. The Collector cursed them silently. Why had they to bring these useless possessions?

Colonial power compels colonised people to produce commodities for commercial profit. People’s lives and liberties are turned into things. And things are everywhere in The Siege of Krishnapur. The Collector and the Padre regard modern things as the objective truth of civilisation. Fleury and the Magistrate have their doubts.

In these two chapters, people become things, and things become people. In the record room, the Magistrate stands

with his head against a bank of cinnamon-coloured documents which so nearly matched the colour of his own hair and whiskers that for a moment it seemed as if his eyes, nose and ears were floating disembodied above the morning coat.

He becomes the colonial archive. Meanwhile, the Padre delivers a sermon to ‘those dim, sinful ranks of jars’ at the back of the church. They have turned away the native Christians and used the church as a storeroom. But the jars 'remained deaf to the exhortations which echoed round their stony ears.’

Elsewhere, Fleury can’t escape the feeling that he’s talking to Chloé the Spaniel, and not Louise Dunstaple. At the Treasury, the sepoys have changed out of their uniforms and stuffed their trousers with silver rupees, so that ‘it seemed that they were staggering away with heavy, trunkless men on their shoulders.’

The line between people and things blurs, like those Houses of the Labouring Classes at the Great Exhibition, which were ‘square and simple’ like ‘the British working man himself.’

The Collector attaches meaning to the ridiculous contents of his collection and feels physically assaulted by the bric-a-brac brought into the Residency: a stuffed owl glares accusingly at him with ‘its glittering yellow eyes.’ But he is dimly aware of his own hypocrisy:

He knew now that he should have forbidden everything except food and weapons … but in their place, ah, could he have brought himself to leave behind his statues, his paintings, his inventions?

3. Boy’s own adventure

Strangely enough, they listened quite enviously to Harry talking about the musket shot which had ‘almost definitely’ been fired at himself and Fleury. They wishes they had had an adventure too, instead of their involuntary glimpse of the abattoir.

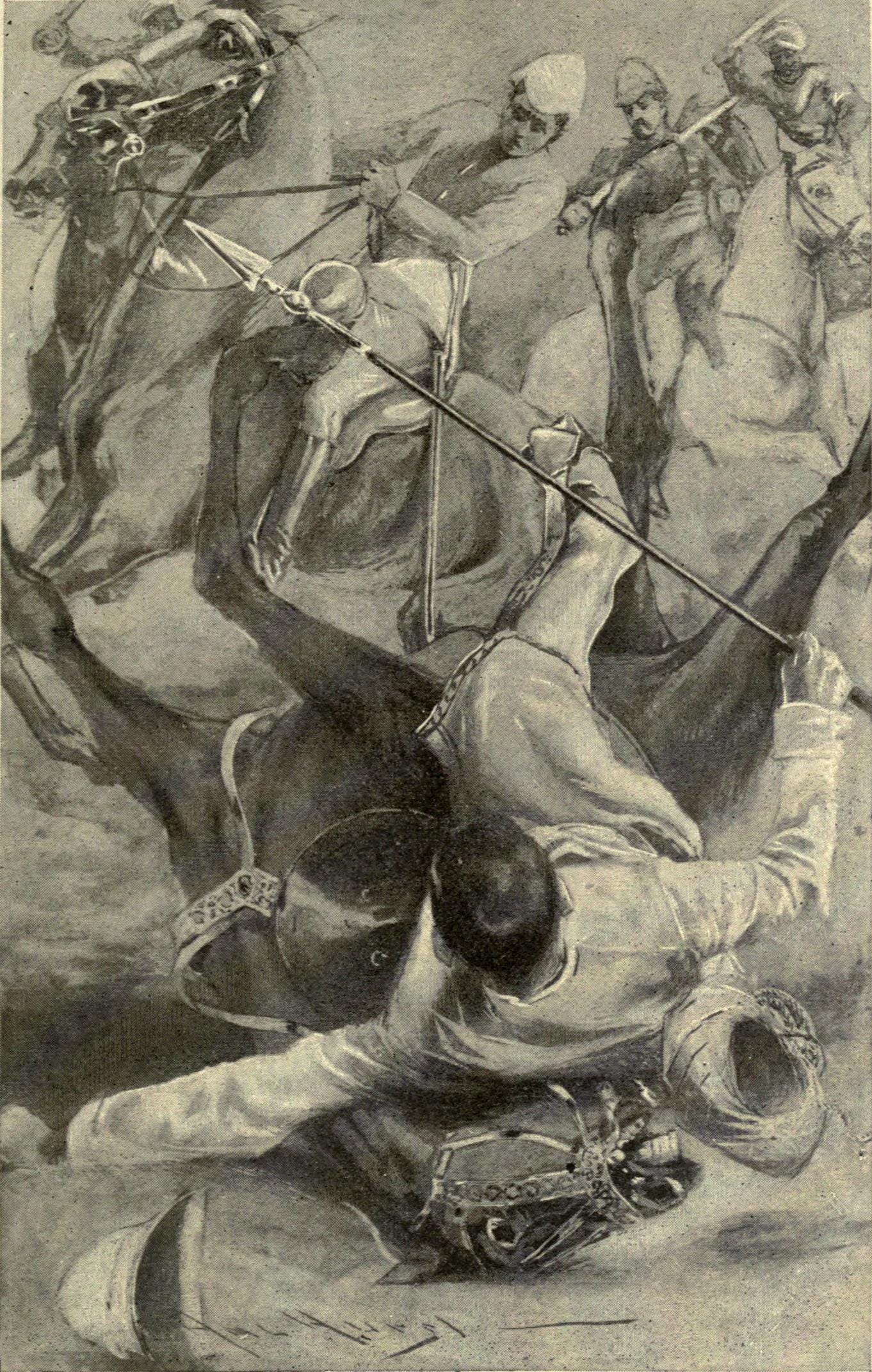

The Siege of Krishnapur is, in part, a pastiche of Victorian and Edwardian adventure stories told to the boys who became Empire builders in the British colonies. Writers like GA Henty, who wrote for The Boy’s Own Paper.

Fleury and Harry clearly grew up on a diet of these yarns of daring-do and are convinced they are the invincible protagonists in a jolly adventure. Their unlikely friendship happens all the time in stories. And rescuing a ‘fallen woman’ is ‘exactly the sort of daring and noble enterprise’ that appeals to their imaginations.

rescuing girls at the gallop was very much their cup of tea, they thought.

But they are pretty useless at it and oblivious to the danger closing in. They cannot convince Lucy Hughes that life is worth living when they barely realise how precious their own lives are. In contrast, their Sikh guards know exactly what is happening and that this is no adventure story.

The real story of the mutiny is incomprehensible to them. It has no place in a ‘boy’s own’ narrative and comes to Fleury and Harry in confused accounts from Captainganj:

Each of them simply had two or three terrible scenes printed on his mind: an Englishwoman trying to say something to him with her throat cut, or a comrade spinning down into a whirlpool of hacking sepoys, something of that sort.

These soldiers ‘had never seen a dead person before … a dead English person, anyway.’ Empire fiction is full of dead natives, but they are entirely unprepared for the story they are now in.

Footnote: How did imperialism permeate boys’ adventure fiction in the Victorian era? (HistoryHit)

4. In Time of Wars and Tumults

Presently the Padre’s voice rose above them, reciting the Prayer in Time of Wars and Tumults …

The Padre’s words come from The Book of Common Prayer, the book first introduced in 1549 under the supervision of England’s first Protestant Archbishop, Thomas Cranmer.

In the 1662 version, War and Tumults follows Dearth and Famine in a list of ‘Prayers and Thanksgivings upon Several Occasions’. It feels gloriously English that the first two prayers on the list are ‘for rain’ and ‘fair weather.’

The phrase ‘wars and tumults’ is spoken by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke:

And when you hear of wars and tumults, do not be terrified, for these things must first take place, but the end will not be at once. (Luke 21:9)

Christ is talking about the end of the world and the Day of Judgment. The Indian Rebellion will not mark the end of the British in the subcontinent, but perhaps the ‘birth pains’ (Matthew 24:6-8; Mark 13:7-8) of Indian independence.

Tumult is a fabulous word. A state of confusion or disorder. There is so much tumult in this book.

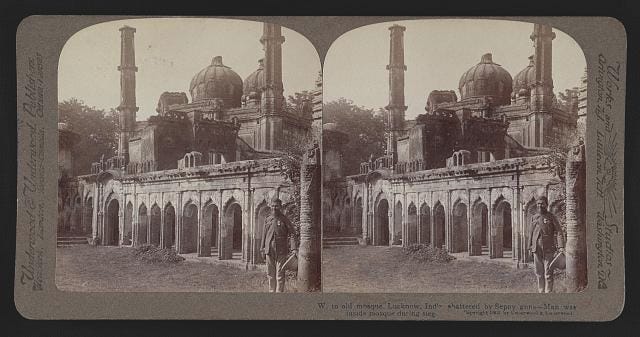

5. The Mosque at Lucknow

He saw the Magistrate shift his gaze to the mosque and knew what he was thinking. He himself, as it happened, was coming to see the mosque less as a sign of his own largeness of mind than as a source of trouble to the cannons in the flowerbeds.

The Collector and Magistrate approve of the destruction of the Krishnapur mosque. At Lucknow, Chief Commissioner Henry Lawrence told his engineers to ‘spare the holy places’ and leave the old mosque standing. During the siege of Lucknow, it was used as cover by sepoy sharpshooters.

6. Nothing to worry about

The banqueting hall stood on a rise of ground which corresponded to the hill beyond the melon beds ... the six pillars of its façade were an echo of the six imposing pillars of its illustrious parent, East India House in Leadenahll Street.

Harry is ‘disappointed to be posted to the safest place inside the enclave’. The Banqueting House echoes the company’s headquarters in London. With its Grecian façade and ‘giant marble busts of Greek philosophers,’ it represents European ‘civilisation’ in India. I strongly suspect it is not the safe enclave Harry fears it to be.

These chapters are peppered with premonitions. Harry’s cannon is liable to distort after several hundred shots, ‘which would take weeks or months of siege warfare.’ Relief should come in the next few days, so ‘Harry had no need to worry about that.’

Meanwhile, Father O’Hara and the Padre are arguing about burial space in the graveyard. The Collector settles the dispute by pointing out that ‘nobody’s dead yet. We’ll talk about it again when you can show me the bodies.’

7. Under the peepul tree

Some distance away, squinting into the glare, the Magistrate could make out Lieutenant Dunstaple and young Fleury talking together in the shade of a peepul tree with the wonderful enthusiasm and sincerity of youth (but which, reflected the Magistrate was, can be a bit sickening if you have too much of it.)

The peepul tree is Ficus religiosa, an Indian species of fig also known as the bodhi tree or ashvattha tree.

Under one such peepul tree, Siddhartha Gautama, attained enlightenment on his path to become the Buddha. In Hinduism, the peepul is the sacred tree of Lord Vishnu, the preserver and protector of good.

What enlightenment have Harry and Fleury attained? Well, Harry is explaining cannons to Fleury. He’s wonderful and enthusiastic about his artillery while fearing that Fleury may not be ‘such a success as he had hoped.’

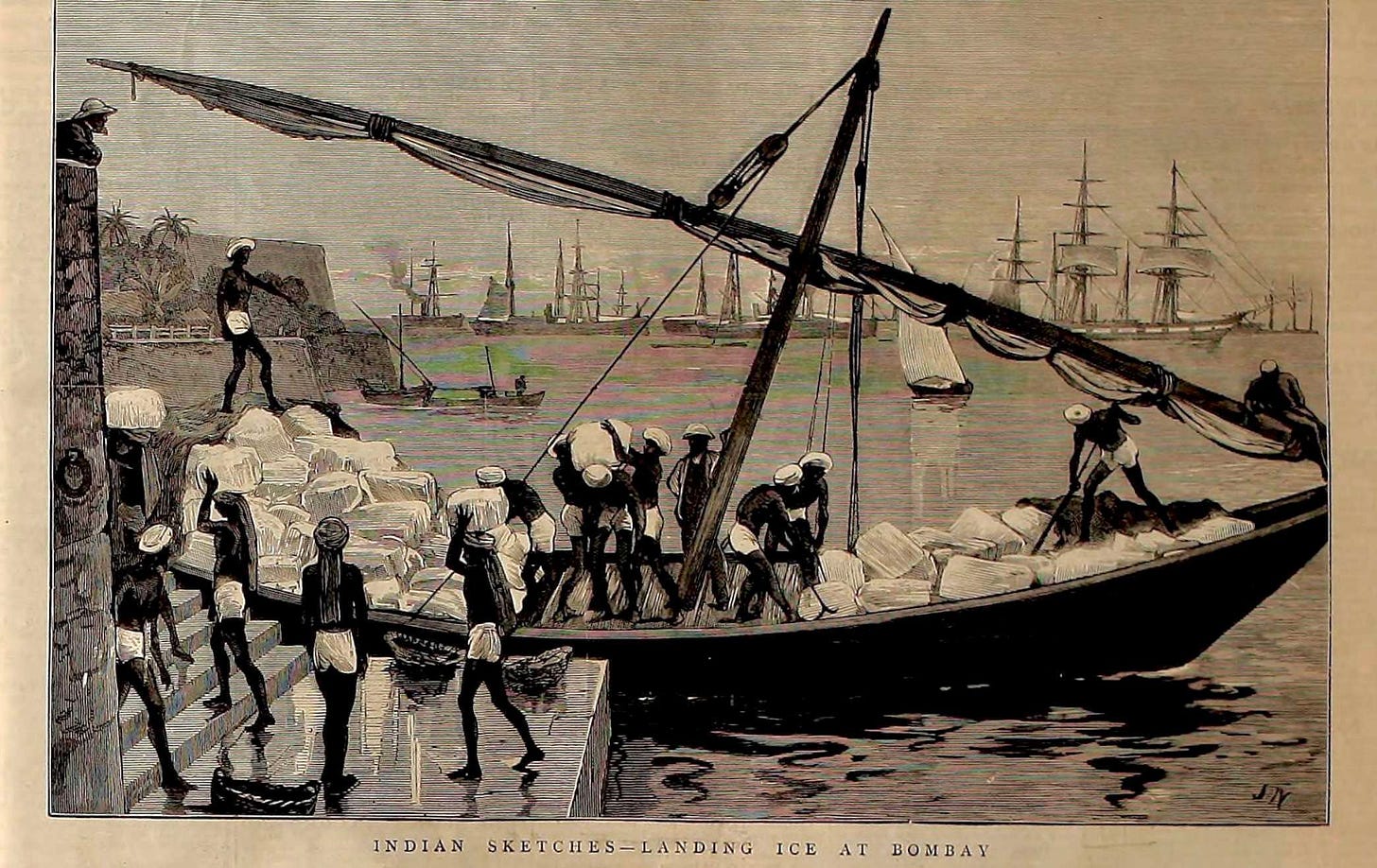

8. Staying cool in the British Raj

It was true that some of the ladies were becoming bad-tempered and disconsolate from the heat, from the absence of active punkahs (the punkah-wallahs were vanishing one by one), and from the scarcity of khus tatties, the frames woven with fragant grass over which water was thrown in rder to cool the air during the hot weather.

I was curious to learn more about khus tatties, which were made from a fragrant grass called vetiver or khus and functioned like natural air conditioners.

Footnote: We need to bring back the ‘Wonder Grass’ that’s kept Indian homes cool for centuries. (The Better India)

This led me to a 1837 poem:

Now kus kus tatties fail to cool

And punkah breeze defying

The mercury marks 95

And we are almost frying.

Still, some relief we may enjoy,

For with our "dall' and rice, Sir,

Liquids become a luxury

From Yankee Tudor's Ice, Sir.

This blessing answers very well,

For sundry other uses

One, as a friend to you I'll tell,

To Comfort it reduces.

Send for a spon (choose a light brown)

At Bathgate's you can get it,

Make a large wig to fit your crown

And with Ice water wet it.

The ‘Yankee Tudor’s Ice’ refers to ice brought by ships from Boston to Calcutta, Bombay and Madras. The Yankee was Frederic Tudor, known as the ‘Ice King’, who made millions exporting ice to the tropics.

Footnote: American Ice in British India (Heritage Lab)

9. On necks and Monty Python

The most that she was prepared to concede was that she might notify them once she had decided not to delay the fatal act any longer, to allow them ‘a last chance’ (provided she did not get drunk again and kill herself spontaneously the way she almost had the other day)

This scene, like many in the book, feels torn from a Monty Python skit. Promising to give her rescuers a sporting chance before she kills herself is a dark bit of British absurdism.

I was interested to read that ‘Fleury and Harry were particularly sensitive to necks.’ It made me think of the Victorians’ apocryphal attitudes towards sex and the myth that they covered up table legs because they were too sexy.

What did Victorians think about necks? All I can find so far is this fascinating bit of doctoral research at the University of Oxford:

The female body through the ages - do necks have a history? (University of Oxford)

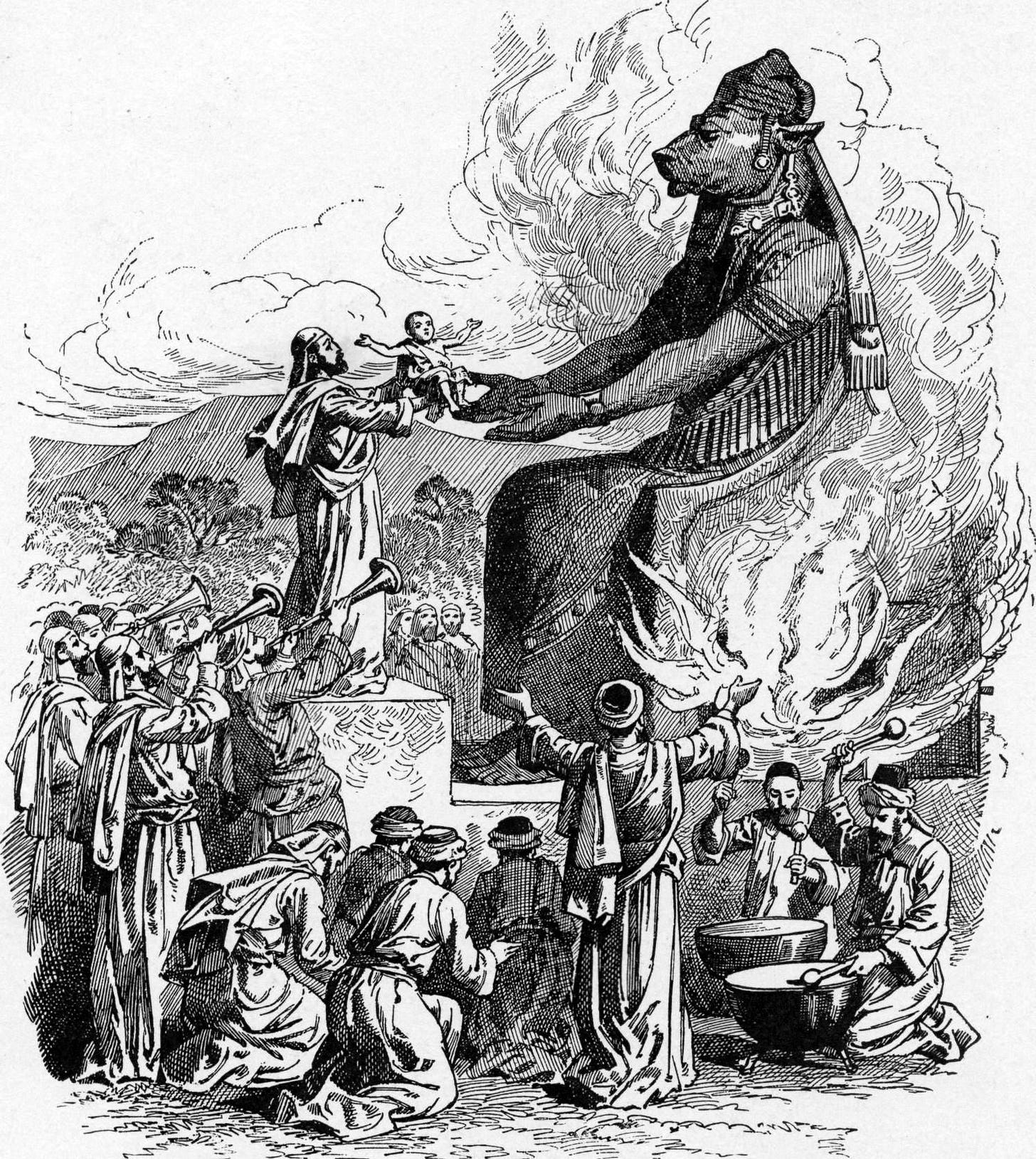

10. Child sacrifice

For example, ancient history gives an account of two hundred children being burned to death as a sacrifice to Saturn … which is, of course, the Moloch of the Scriptures.’ The Padre surveyed the class. ‘You wouldn’t like that, children, would you?’ The children agreed that they would not care for it in the least.

There are so many laugh-out-loud lines in this book, but this one really got me! The deadpan delivery is perfect. With, of course, the dark kicker that these children may be sacrificed in the siege to come.

11. Matthew Arnold

'These are the words a very dear friend of mine from Oxford, a poet (like myself), who is now working as an inspector of schools.'

Fleury’s friend, poet and school inspector is Matthew Arnold. Arnold was a liberal and the author of Culture and Anarchy, in which he attacked the anti-intellectual Philistinism of the Victorian middle class.

He wrote that culture is ‘the study of perfection’ and

… seeks to do away with classes; to make the best that has been thought and known in the world current everywhere; to make all men live in an atmosphere of sweetness and light.

12. Mass-produced silverware

Yes, he remembered sadly, the Magistrate had doubted it, and had scoffed when he had suggested that one day electro-metallurgy would permit every working man to drink from a Cellini cup.

I can’t figure out whether JG Farrell is deliberately alluding to Reinhold Vasters's art forgery. In the 1970s, many pieces by Benvenuto Cellini in British and American museums were exposed as elaborate nineteenth-century forgeries.

The Collector does not realise that the Cellini cup is itself a copy. Does it matter? Perhaps not. But the question of the value of art in the age of mechanical production would become the concern of Marxist cultural theorists in the twentieth century. Is art diminished by its mass production? The Collector thinks not.

Footnote: A Successful Forger: Reinhold Vasters

Watch: Walter Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

13. The Death of Vokins

Vokins lacked the broader view. He tended only to see the prospect of the Death of Vokins. Although some of the Collector’s guests might have been hard put to it to think of what a man of Vokin’s class had to lose, to Vokins it was very clear what he had to lose: namely his life. He was not at all anxious to leave his skin on the Indian plains; he wanted to take it back to the slums of Soho or wherever it came from.

I just want to say that I love Vokins. In this chapter, JG Farrell shows the similar status of the Indians and the British working class in the colonisers' impoverished imagination. Like the Model Houses for the Labouring Classes, Vokins’ interior world is incomprehensible to these people.

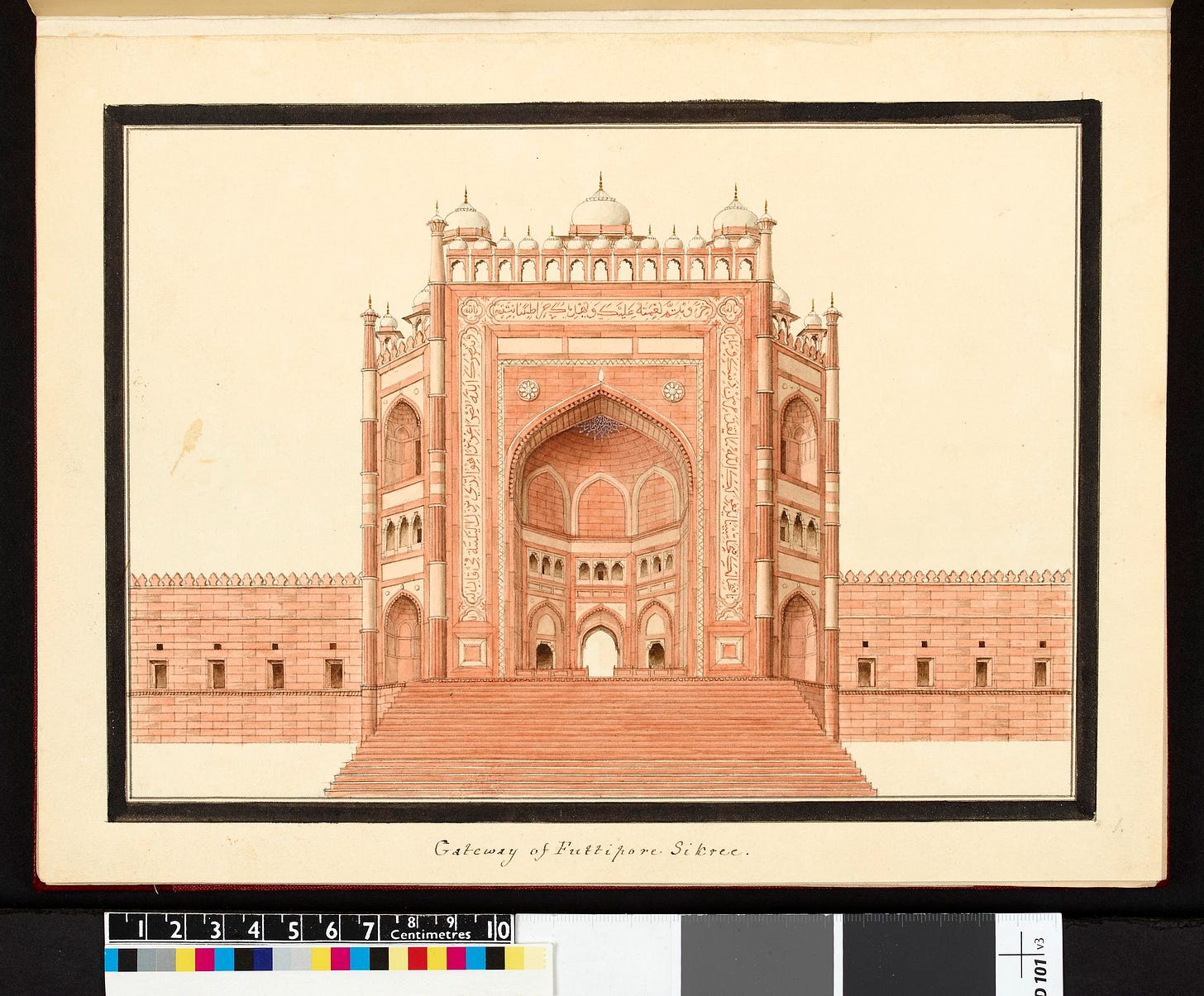

14. The World is a Bridge

He paused at the top, frowning. A ghostly voice had whispered in his ear: ‘The world is a bridge. Pass over it but do not build a house on it.’ Was that a Christian or a Hindu proverb? He could not remember.

These lines are carved onto the Buland Darwaza gate at Fatehpur Sikri. The ‘high gate’ or ‘gate of victory’ is the highest gateway in the world and was constructed in 1573 for the Mughal emperor Akbar to commemorate his victory over Gujarat.

It is written in Kufic script and is attributed to ‘Jesus, Son of Mary (on whom be peace)’. It reads:

The World is a Bridge, pass over it, but build no houses upon it. He who hopes for a day, may hope for eternity; but the World endures but an hour. Spend it in prayer, for the rest is unseen.

So it is neither a Christian nor a Hindu proverb, but a quotation from the Muslim prophet, Īsā ibn Maryam (literally, Jesus, son of Mary). It is a beautiful and attractive saying, that William Dalrymple contextualises in the link below.

It is curious to me that I must have stood beneath the gate when I visited Fatehpur Sikri with my family when I was fifteen. The prophet’s words directly challenge the Collector’s faith in the material objects of civilisation and the colonising mission itself. For who can own the world? It is but a bridge.

Footnote: William Dalrymple reviews The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature by Tarif Khalidi. (The Guardian)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will read Chapters 10–13 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

.

There were so many little touches to love about this chapter (I laughed out loud at Harry and Fleury’s ogling Lucy’s neck and arms so much that they were incapable of killing a mosquito, for example). But for me the very finest moment came at the end of chapter 9, when Lucy, thanks to a letter from Louise, makes it to safety in the nick of time.

Until this week’s reading, we had only seen Louise from Fleury’s and Harry’s perspectives, and so she came off as an empty-headed beauty and exemplar of pure womanhood. In Fleury’s eyes, she isn’t even human but resembles Chloë the lapdog—ornamental, meant for others’ amusement, and ominously subject to being disposed of once she ceases to amuse.

How wonderful to discover that Louise in fact is 1. Kind and practical. She takes care of all those children who (hilariously) are driven to tears by the Padre’s wretched sermons. 2. Not at all uptight. Her brother may wish to shield her from “contamination,” but Louise obviously thinks this is stupid and that in fact Lucy was more sinned against than sinning. Louise’s letter, promising friendship to Lucy, is a model of true Christian behavior—if only the high-minded and judgmental men would learn from her example!

(I just want to say that I love Vokins. In this chapter, JG Farrell shows the similar status of the Indians and the British working class in the colonisers' impoverished imagination)

-- There is much to be said about this, and dare I say, I wonder if something of this attitude persists today.

Simon your commentary is so rich as always. Your comments on how indigo cultivation was transmitted across the empire, how the empire was a structure for something that may be called 'globalisation' reminded me of how when I visited Kenya, where my great grandfather arrived to build the railways in the 1930s from India. They needed carpenters, and that skill threw them to another continent, all within the structure of the empire. Thus a diaspora was created in east Africa (which subsequently produced a British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak). History is a great churning and scattering and transmission. And it is full of many ironies, both dark and light.

Reading this too, I was reminded of VS Naipaul, whose ancestors were transmitted along the empire structure to the Caribbean, to work in the sugar plantations. I wonder what Naipaul thought of Farrells's novels, if he thought of them at all. Naipaul is very much interested in the aftermath of imperialism, the dislocations and disruptions and the psychological exploration, Farrell has a really vast vision which is rooted in close detail and dark humour centred around the circumstances of the colonial class. Farrell observes the decline from the perspective of the imperial caste, in Singapore Sling & Krishnapur & Troubles, Naipaul observes the psychological terrain of the aftermath of empire in his Trinidad novels, The Mimic Men, A Bend in the River and others.

I also laughed out loud at points. Farrell's wit is a delight. The themes so deep and serious, the events so dark, but it has these moments of comedy. This is what distinguishes Farrell, makes his brew unique.