Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 5 & 6

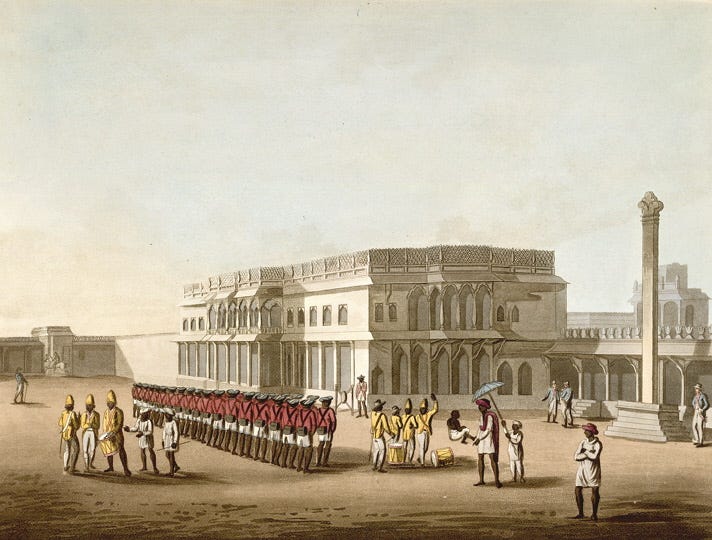

The Collector pays a routine visit to the opium factory, and George Fleury and Harry Dunastaple make a courtesy call to the Maharajah and his son, Hari. Much to Fluery’s displeasure, Miriam accompanies the Collector in order to see the workings of the factory.

Fleury meets Hari, and Harry Dunsataple falls ill and is left in the care of the Maharajah’s Prime Minister. Hari takes Fleury to see his sleeping father. He shows Fleury curiosities from their collection and notes the Englishman’s boredom.

Fleury believes they share a common distaste for materialism, but Hari is offended by Fleury’s denigration of his ancestors and dismissal of British technological progress. As he makes a daguerreotype, Hari decides that Fleury is ‘a very backward man.’

Meanwhile, Miriam tries to stay awake in the poppy-scented air of the opium factory, as a man with flaky skin gives her the tour. On the ride back to the cantonment, she finally succumbs to sleep as the Collector drones on about the progress of mankind.

The Magistrate argues with a group of landowners, sacrificing a black goat to stop the river from flooding. They laugh at him when he has left, and spirits rise higher on news of a massacre of foreigners at Captainganj. Meanwhile, the Collector is smug amongst his collection, believing himself to be ‘a whole man.’

The General arrives injured from Captainganj, and news of the massacre reaches Fleury and Harry at the Maharajah’s palace. Harry’s first reaction is disappointment in missing out on the action.

Footnotes

1. Maharajahs and Zemindars

Miriam Fleury accompanies the Collector on a visit to the opium factory while her brother George joins Harry in a courtesy call to the Maharajah. Maharajah comes from Sanskrit and means ‘great ruler’.

In British-controlled India, around 500 royal princes had varying degrees of autonomy over their domains. The British involved themselves in the education and appointment of these rulers, creating an elite sympathetic to British rule that would help suppress dissent.

Zemindars (or zamindars) are feudal landowners. The British elevated some of these to the status of maharajahs.

Footnote: Did India let down the Maharajahs?

Footnote: The End of the Maharajas

Footnote: The illiterate boy who became a Maharaja

2. Masculinity at the Maharajahs

[The Collector] set himself to explain to Fleury about the character of rich natives: their sons were brought up in an effeminate, luxurious manner. Their health was ruined by eating sickly sweetmeats and indulging in other weakening behaviour.

Farrell continues to develop the theme of colonial masculinities. Since his arrival in India, Fleury has tried to change his spots, to become less of a brooding romantic and more ‘broad-shouldered’, in a rather ineffectual attempt to appear attractive to Louise Dunstaple.

His attempts to be more manly are frustrated (in his eyes) by the presence of his older sister, who calls him ‘Dobbin’ and shows far too much interest in machinery, factories and the Collector. He feels further emasculated by Lieutenant Cutter, riding into bungalows, sabre drawn, on his champagne-quaffing horse.

The Collector and Harry Dunstaple reproduce British racist stereotypes of Indians as weak and effeminate:

‘You have to be careful thrashing a Hindu, George, because they have very weak chests and you can kill them.’

Harry’s father makes a spurious scientific claim about the weak hearts of Indians. Later, Fleury will tell Hari that ‘an engine has no heart’ as he tries to find common philosophical ground between him and the Maharajah’s son. And the Collector thinks himself superior to the Magistrate because:

‘The trouble with poor Willoughby … is that he’s not a whole man, as I am … For science and reason is not enough. A man must also have a heart and be capable of understanding the beauties of art and literature.’

But Harry’s statement about weak Indians is loaded with irony as he keels over on arrival at the Maharajah’s palace. This ‘broad-shouldered’ lieutenant is beset with illness and injury, and is oblivious (or ashamed) that he has been put in the dutiful and diligent care of the Prime Minister.

Hari poses a problem for Fleury’s shifting sense of self. There is something sympathetic, amiable and spirited about this young man, a breath of fresh air from the stuffy lectures of the Collector, and the dim-witted Harry Dunstaple. Hari seems to share his romanticism, that religion and civilisation should ‘lift up our hearts.’ (More hearts).

But he is mistaken and Hari finds him a disappointment, ‘a very backward man.’ Once again, Farrell explores his characters’ misconceptionof the world around them.

Further reading: Colonial masculinity: The 'manly Englishman' and the 'effeminate Bengali' in the late nineteenth century by Mrinalini Sinha

3. Zouaves

The hollowed-out space seethed with soldiers, some practically naked, others amazingly uniformed like Zouaves with blue tunics and baggy orange trousers and armed to the teeth with daggers and clubs.

The Zouaves were French light infantry, initially recruited from the Zwawa Berbers of Algeria, from whom they acquired their name and distinctive uniform. In 1856, the British army adopted the Zouave uniform in the West India Regiments stationed in the Caribbean. Today, military bands in Jamaica and Barbados still wear it.

4. Blackwood’s Magazine and antler chairs

Near a fireplace of marble inlaid with garnets, lapis lazuli and agate, the Maharajah’s son sat on a chair constructed entirely of antlers, eating a boiled egg and reading Blackwood’s Magazine.

Fleury mentally groups together the antler chairs with all the other curiosities in Hari’s collection:

'A spear that shoots someone as well as stabbing him? Ludicrous! And all these other things you have shown me, collections of this and that, sea-shells and carved ivory, disgraceful pictures, chairs made of antlers and astronomical clocks, d'you know what they remind me of?'

They remind him of the Great Exhibition, which is curious because antler chairs and furniture were among the novelties displayed in London in 1851. This seems like another example of Fleury’s misrecognition: this supposed Indian oddity is, in fact, a German import, a décor fad that would take over the world in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Hari is reading a copy of Blackwood’s Magazine: ‘A boiled egg and Blackwood’s is the best way to begin the day.’ This was a conservative monthly literary review known for its horror fiction and an influence and inspiration in the writing of Charles Dickens, the Brontë sisters, and Edgar Allan Poe.

In 1899, Blackwood’s Magazine was the first to publish Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, a novel that critiques European colonialism in Africa. Blackwood’s is also mentioned by George Orwell in Burmese Days. Readers have already remarked on the similarity between the names Fleury and Flory, the protagonist of Orwell’s dark portrayal of the British in Burma:

Dull boozing witless porkers! Was it possible that they could go on week after week, year after year, repeating word for word the same evil-minded drivel, like a parody of a fifth-rate story in Blackwood's? Would none of them ever think of anything new to say? Oh, what a place, what people! What a civilization is this of ours—this godless civilization founded on whisky, Blackwood's and the Bonzo pictures!

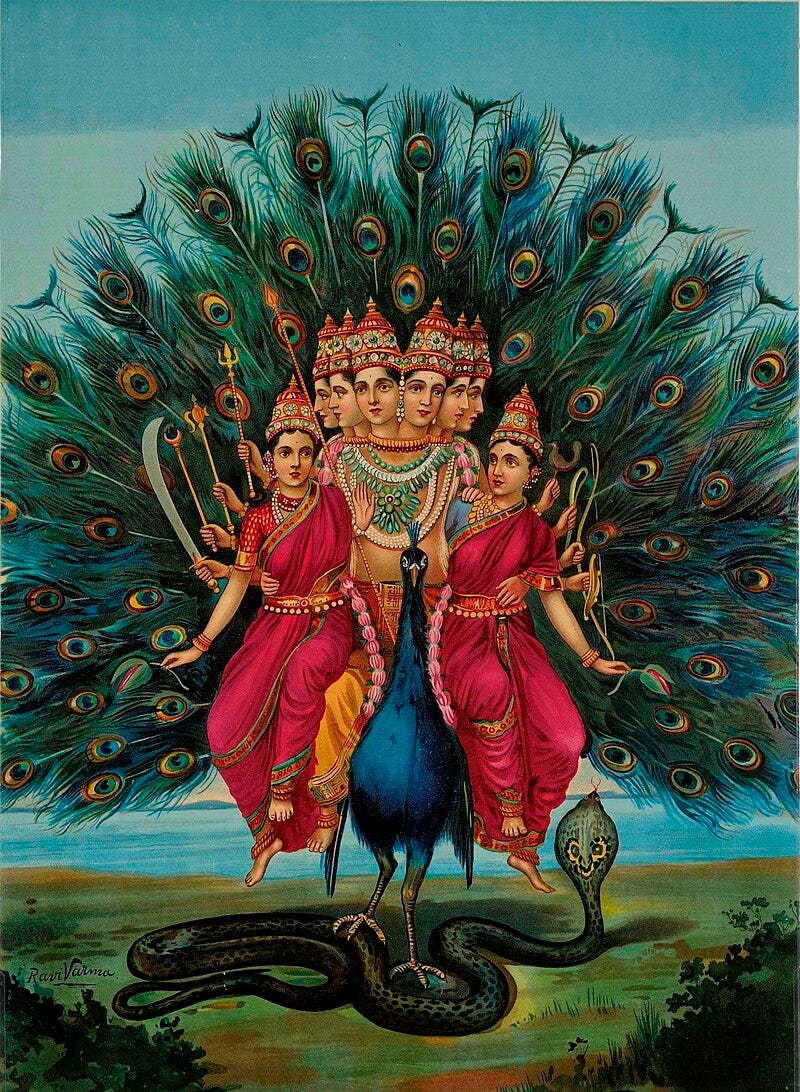

5. Kartikeya in the forest of symbols

He had forgotten for the moment just what sort of religion it was that Hari enjoyed … a mixture of superstition, fairy-tale, idolatry and obscenity, repellent to every decent Englishman in India.

Kartikeya is the god of war, as well as the lord of serpents. In Hindu iconography, his peacock mount stands on a snake, a symbol of time. There is a distant echo of this image in the Collector’s rather ridiculous sculpture, Innocence Protected by Fidelity, in which ‘a scantily clothed young girl’ is defended from ‘a gagging snake’ by her faithful hound.

There’s a lot going on here, including the inability of the British to understand the spirituality of Hinduism. But I think Farrell is also exploring our general incomprehension of other people’s religious imagery. In the Collector’s favourite room are his ‘many beloved objects.’ The most important is a bas-relief in marble called The Spirit of Science Conquers Ignorance and Prejudice.

We are being invited to laugh at the Collector. But these absurd pieces of art mean something to him, as the story of Kartikeya means something to Hari, and his father’s Bible means something to Fleury. And yet these objects and symbols seem somehow insufficient to the task of communicating how they ‘lift up our hearts’. As Fleury says to Hari,

‘Objects are useless by themselves. How pathetic they are compared with noble feelings! What a poor and limited world they reveal beside the world of the eternal soul!’

But other people’s symbols are too alien and exotic for us to identify with. They are dangerous or repellent, so we neutralise them with laughter or scorn, or as Fleury does by reducing the Hindu religion to ‘a charming story’:

Six babies pressed by love into one, there was surely no harm in such a pleasant fairy story.

6. In the arms of Morpheus

The Collector talked on and on but Miriam, soothed by the heat and the poppy fumes, cradled by the worn leather upholstery of the landau, found that her eyelids creeping down in spite of herself.

Fleury thinks Hinduism is ‘a pleasant fairy story’, but there is a fairy tale air to this chapter – and it is more Brothers Grimm than Disney. The Maharaja’s Palace appears to be under some kind of enchantment. Fleury and Harry pass sleeping soldiers, and inside, Harry immediately succumbs to some strange sickness. Hari exhibits his sleeping father like an object in his collection. I would not be surprised to learn that the Maharaja had been asleep for a thousand years.

Fleury stifles his yawns as Hari shows him around. Meanwhile, his sister is fairing no better in the poppy-scented opium factory. Sleep is everywhere. Opium is a pain-killer and induces sleep. Alongside the other themes of this chapter, hearts and religion, I can’t help but quote Karl Marx:

Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The British are sleepwalking towards destruction and clinging onto ideas of progress and civilisation, as the ‘oppressed creature’ clings to religion, and the opium eater clings to his addiction.

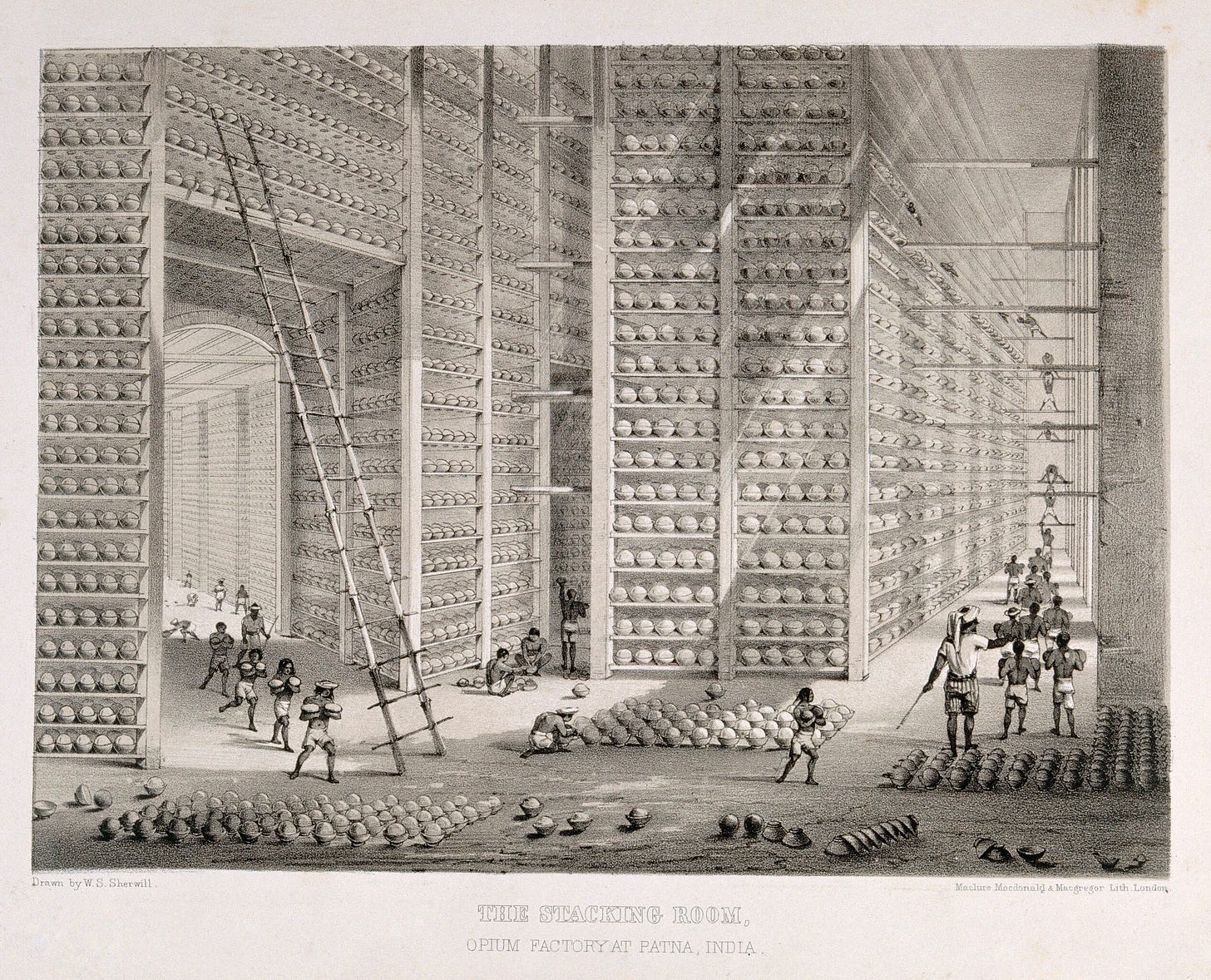

7. The Opium factory

She felt wonderfully at peace and was sorry when at last the tour came to an end and she was taken to watch the workmen making the finished opium into great balls, each as big as a man’s head, which would be packed forty to a chest and auctioned in Calcutta.

Opium was the second largest source of revenue for the British Raj after land tax. At the start of the century, the opium factories exported 4,000 chests a year. By 1880, this has risen to 60,000. As well as precipitating two wars with China, the British opium trade impoverished and exploited millions of Indian peasants, trapped in a coercive system of compulsory poppy production.

8. Hindu asceticism in British India

‘One can’t help but admire the rigour with which they pursue their beliefs.’

The naked ‘devotee of Siva’ is yet another example of other people’s hearts being inaccessible or unfathomable to the spectator. The Collector seems a little disappointed that Miriam is too drugged up on the opium poppy to be appropriately shocked by the wandering ascetic.

Ascetics had traditionally formed militias to control trade routes across the subcontinent. The East India Company did not distinguish between yogis and other ascetics, and in 1773, it outlawed the practices of wandering naked or carrying a weapon.

In the 1770s, the Company clashed with Sannyasi ascetics in Bengal. The rebellion inspired the novel Anandamath by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and the national song of India, ‘Vande Mataram’, symbolically integrating the rebellion into the struggle against colonial rule.

Footnote: The yogi as hermit, warrior, criminal and showman.

Footnote: Ascetics and Yogis in Indian painting.

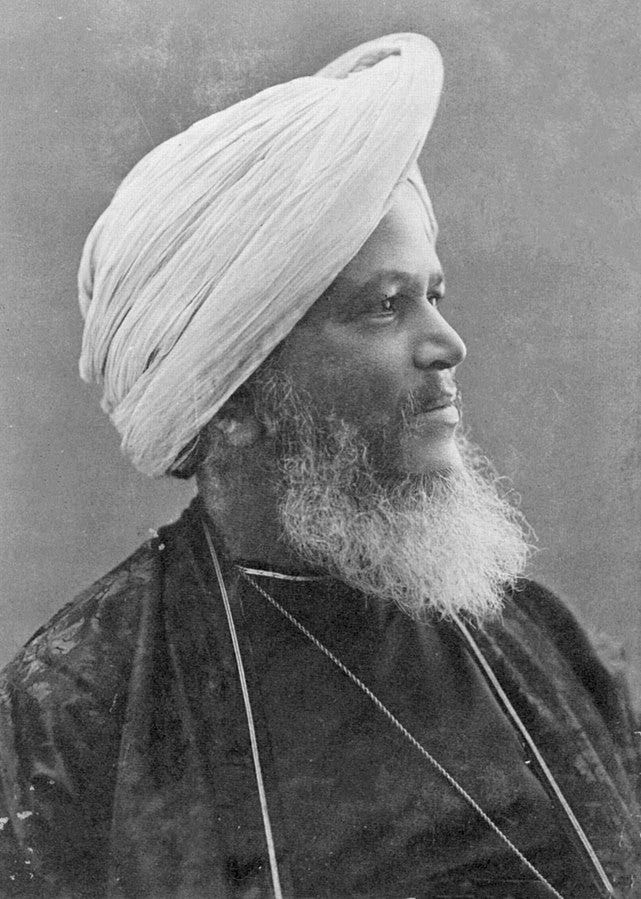

9. Daguerreotypes in India

My dear Hari, Plato did more for the human race than Monsieur Daguerre.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was born in France in 1787. In the 1830s, he captured the first photographic image, which was thence called a daguerreotype. ‘I have seized the light.’ he said. ‘I have arrested its flight!’

The technology spread rapidly. In 1840, the first advertisements for imported cameras appeared in Calcutta, and the oldest photographic image in India is a daguerreotype of the Sans Souci Theatre that same year.

The Italian-British photographer Felice Beato made the Crimean War the first photographed conflict. In 1857, he was in India to document the mutiny and uprising. His pictures of Lucknow are possibly the first photographic images of corpses.

One of the first professional Indian photographers was Lala Deen Dayal, who served as the court photographer to the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Footnote: India’s earliest photographers

10. Irrelevant rubbish

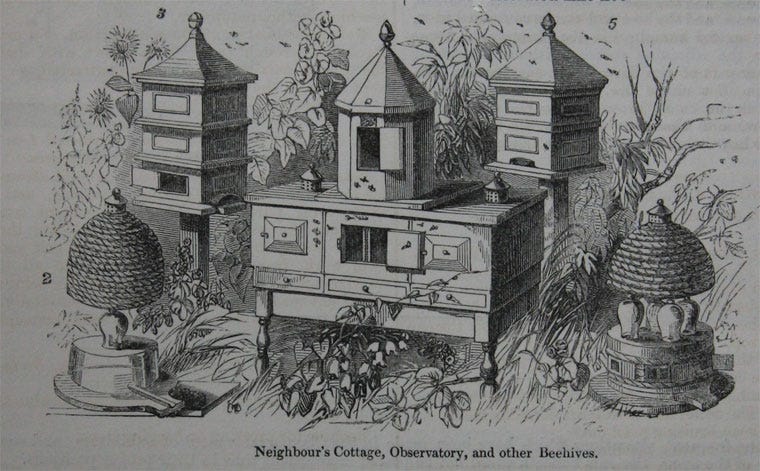

'Take the Indian Court in the Crystal Palace, it was full of useless objects. There were spears, a life-sized elephant with a double howdah, swords, umbrellas, jewels, and rich cloths ... the very things you have just been showing me. In fact, the whole Exhibition was composed merely of collections of this and that, utterly without significance ... There was an Observatory Hive ... ah, the tedious comparisons that were made between mankind and the hive's "quietly-employed inhabitants, those living emblems of industry and order"!'

11. From Franks to Feringhee

Their glee redoubled when soon after the Magistrate’s departure they heard that there had been a massacre of the feringhees at Captainganj.

Europeans sailed west in search of a new trade route to the east. Thinking they had reached Asia, they called the people they encountered ‘indians’, only to discover later that they were far from India.

The Franks were the Germanic peoples of the most northern provinces of the mainland Roman Empire. They were united under Charlemagne in 800. Seventy years later, the Carolingian Empire was divided, forming the antecedents of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Through the medieval period, the Muslim world referred to Christian Europe as Frangistan, and in the fourteenth century, the Mongols knew Europeans as the Franks. The Mughal Empire in South Asia inherited the term for westerners, calling them ‘firangi’.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will be reading Chapters 7, 8 and 9 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

thank you Simon, so much to think about as always.

As an aside, the relationship between the British aristocracy and the royal of houses of India is fascinating. A good book about an interesting figure is Anita Anand's "Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary" - about the granddaughter of Maharjah Ranjit Singh, who was raised at Hampton Court Palace, as the Goddaughter of Queen Victoria. All of the complexities of the Anglo-Indian experience and history contained in one life.

I cringed as George railed against the “useless rubbish“ that Hari’s ancestors had collected somehow thinking that Hari believes the same thing. But he has grossly misread the situation and doesn’t realize it until it’s too late.