A serious chat about civilisation

The Siege of Krishnapur: Chapters 3–4

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 3 & 4

This week, we are reading chapters 3 and 4. George and Miriam Fleury arrive in Krishnapur, in the company of Harry Dunstaple. Fleury moves into the Joint Magistrate’s bungalow and then goes to dinner at the Residency. There is a serious chat about civilisation, in which Fleury says a little more than he intended.

The next day, he accepts an invitation from Rayne, the Opium Agent, where he learns of the mutiny at Meerut. The wolfish Lieutenant Cutter barges in on his horse and orders some brandy, and Fleury exits early before Rayne can quiz him on the nature of civilisation.

Meanwhile, the Collector is having trouble sleeping. Dr. NcNab comes to administer a sleeping draught, and the Collector asks him about God and religion. The Collector considers how to respond to the news from Meerut and despairs at General Jackson, who arrives with a cricket bat and seems unconcerned about the fires at Captainganj.

A week of indecision follows as the British argue about whether to stay calm and carry on, or bolt to the Residency and hide behind the walls.

Footnotes

1. Griffins and cemeteries

The Fleury siblings, George and Miriam, arrive in Krishnapur in April, just as unrest begins to spread across northern India. They travel by dak gharry, a horse-drawn post chaise, and pass the cemetery we saw in the opening pages. This is the third consecutive chapter in which cemeteries are mentioned.

Footnote: An interesting discussion on the origin of the term ‘Griffin’ for newcomers in India.

Footnote: A dak gharry.

Tangent: The Gryphon – Indo-European Guardian of the Golden Realm.

2. Pig-sticking

Harry Dunstaple has sprained his wrist pig-sticking. This pastime was mentioned in the previous chapter. This was boar hunting with a long spear and was encouraged by the military authorities. According to the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

As a startled or angry wild boar is a fast runner and a desperate fighter the pig-sticker must possess a good eye, a steady hand, a firm seat, a cool head and a courageous heart.

Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell wrote a book on the sport and claimed:

Not only is pig-sticking the most exciting and enjoyable sport for both the man and horse as well, but I really believe that the boar enjoys it too.

3. Captain Lang and the Siege of Sevastopol

In Chapter 2, we learned that Miriam Fleury lost her husband before the siege of Sevastopol. Captain Lang was fighting in the Crimea against the Russian Empire. When Miriam mentioned her husband’s death, the Collector felt she had taken ‘an unfair advantage’ by ‘dragging in a dead husband to put’ him in the wrong.

Lang links this siege story to another at Sevastopol and to one of the first modern wars. The Crimean War was one of the first to be documented by photography and became infamous for its military and medical mismanagement. Leo Tolstoy was there, and Florence Nightingale revolutionised the treatment of wounded soldiers.

4. Chloé

Fleury did not himself particularly care for dogs, but he new that young ladies did, as a rule. He had bought Chloé, whole golden tresses had reminded him of Louise, from a young officer who had ruined himself at the racecourse,

The little spaniel, ‘watching with amazement the dust that billowed from beneath the wheels’, made me think of Queen Victoria’s dog Dash. Fleury’s pursuit of Louise is tragi-comic: he is evidently not her type. And he is painfully aware that he will not ‘shine’ in this country of ‘discomfort and snakes.’

The dog is his ‘first salvo aimed at Louise’s affections.’ The military metaphor has a chill to it, given the events that are about to unfold.

5. Fleury’s luggage

Amongst Fleury’s luggage is some Brown Windsor soap, supposedly the same used by the young queen Victoria, and embossed with a picture of Windsor Castle. It was produced by Yardley & Statham and was exhibited at the Great Exhibition in 1851. Yardley of London still makes soaps today.

Bell’s Life was a Victorian sporting weekly sold predominantly to the British working class and with a focus on horse racing and boxing. You can look at an 1848 issue here.

His ‘ingenious piece of furniture’ may have looked a bit like this. Fleury hopes never to have to use it. His fear of snakes, his queries about ‘white ants’ (termites); the disturbingly strong scent of roses. Here is a man who would much rather be at home:

At that moment, tired and dispirited, he would have given a great deal to smell the fresh breeze off the Sussex downs.

6. The Collector and Caligula

Mr Hopkins is the District Collector at Krishnapur. As the name suggests, this was originally a tax-collecting position in the East India Company, but it came with much more wide-ranging administrative powers. Indeed, at Krishnapur, Mr Hopkins is ‘the supreme authority’, and in Harry’s view, his power resembled that of a Roman emperor.

It was in the nature of things that sometimes a Roman emperor, or a Collector, would go mad, insist on promoting his horse to be a general, and would have to be humoured; such a danger exists in every rigid hierarchy.

This is an allusion to Emperor Caligula, who made his favourite horse, Incitatus (‘swift’), into a Consul. Except he probably only threatened to do so, and perhaps only to mock a rather useless Senate, as Mary Beard explains here.

7. The Gorse Bruiser

It was a rectangular metal box with a funnel at one end and cog-wheels on both sides.

This peculiar device was exhibited by Charles Burrell and Sons at the 1851 Great Exhibition (it won a Prize Medal). It is one of those absurd Victorian inventions that the Collector imagines will bring civilisation to the subcontinent. He quotes from the Exhibition’s catalogue:

The progress of the human racce, resulting from the labour of all men, ought to be the final object of the exertion of each individual.

This machine for tenderising animal feed reminds me of Hilary Mantel’s use of the resemblance between household objects and instruments of torture to make the reader feel uncomfortable and unsettled.

Fleury’s hunger prevents him from thinking lofty, noble thoughts of civilisation. This mirrors the moment in Calcutta, where Louise’s ‘ethereal’ beauty is offset by the duck leg she is feeding to the wolfish Lieutenant Cutter.

8. On Opium and Steamships

‘For is this not at once a prodigious material triumph and an emobidment, by God’s grace, of the spirit of mankind?’

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s iron-hulled steamship, the SS Great Eastern, was launched in 1855 – the largest ship of its day. She could carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling, a capacity not surpassed until the German ocean liner SS Imperator in 1913 – The Titanic (1912) carried 2,453 passengers.

Mrs Rayne champions her husband’s business of supplying China with opium. ‘That’s what I call progress!’ Britain was currently engaged in a war against the Qing dynasty to force the Chinese government to accept imports of this highly addictive narcotic.

China’s defeat in 1860 did not feel like ‘progress’ to the Chinese, who watched Europeans loot the Old Summer Palace in Beijing and enforce unequal trade agreements on the government.

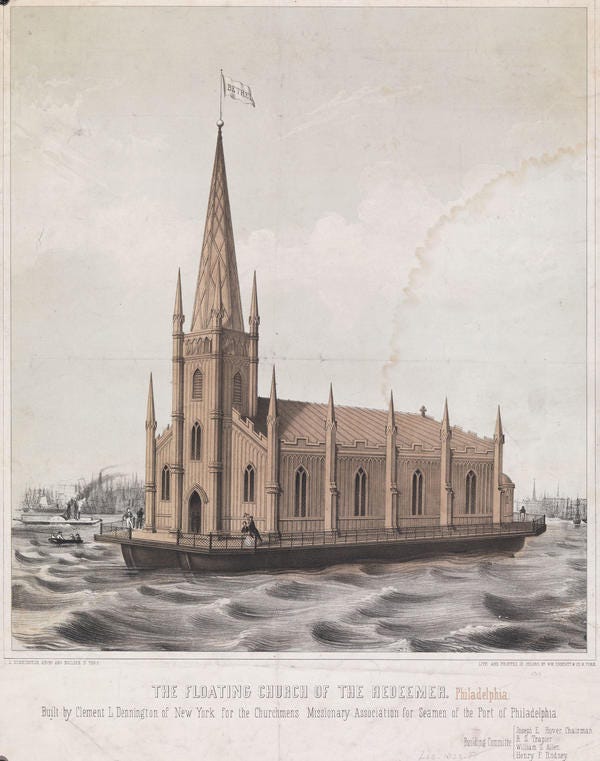

9. Floating Church for Seamen

This unusual construction floated on the twin hulls of two New York clipper ships and was entirely in the Gothic style, with a tower surmounted by a spire.

This was one of a handful of floating churches constructed in the United States to serve sailors and dockworkers. You can read much more about it here.

Fleury’s anxious contradictions make him a compelling central character in our story. He thinks ‘a woman’s special skill is to listen quietly to what a fellow has to say’, but what he has to say is evidently of no interest to Louise. His civilised thoughts are sabotaged by his grumbling belly, and his high falutin opinions blindside his amorous gameplan:

He had meant to say none of that … he had meant to be blunt and manly and to smile a lot. What a fool he was! As he sat there a random, frightening thought occured to him: tonight he would have to sleep in the midst of sipping snakes!

10. ‘Every invention is a prayer to God’

‘Every invention, however great, however small, is a humble emulation of the greatest invention of all, the Universe.’

Hughes' typograph for the blind won a Gold Medal at the Great Exhibition. When Queen Victoria visited Manchester’s Henshaw’s Blind Asylum, she was ‘filled with astonishment and admiration’ when a blind student called Mary Pearson typed out ‘Her Most Gracious Majesty.’

Footnote: Read more about Hughes’ typography here.

11. Lord Bhairava

Peering closer, Fleury saw that people had left coins and food in the bowl he was holding and more food had been smeared around his chuckling lips, which were also daubed with crimson, as if with blood.

In Hinduism, Bhairava is a manifestation or avatar of Shiva, the deity of destruction who transforms the universe. In the tradition of Shaivism, where Shiva is worshipped as the supreme being, Bhairava punishes Brahma, the creator, for his arrogance and dishonesty. His name means frightful of fearsome form, and he clearly scared the bejesus out of George Fleury.

I would love to hear from South Asian readers about why we might be meeting Lord Bhairava at this point in our story. From what I understand, Bhairava is a punisher of sins, especially of the kind the British are guilty of: a deluded sense of their own superiority.

12. On naming things

Fleury sipped his champagne which had an unpleasant, sour taste.

At Rayne’s bungalow, they only drink champagne, and they smoke cheroots, long cigars that originated in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The name cheroot comes from Tamil via Portuguese. Rayne calls the champagne simkin, an Anglo-Indian corruption of the Urdu word for champagne.

The Opium Agent and his guests use words from Arabic, Urdu and Tamil to describe things and themselves (‘sahib’, master; ‘mems’ from memsahib, mistress), but they deny the servants their real names, giving them animal names in English: Ram, Monkey, Ant.

While outside, Chloé is tied up and moaning.

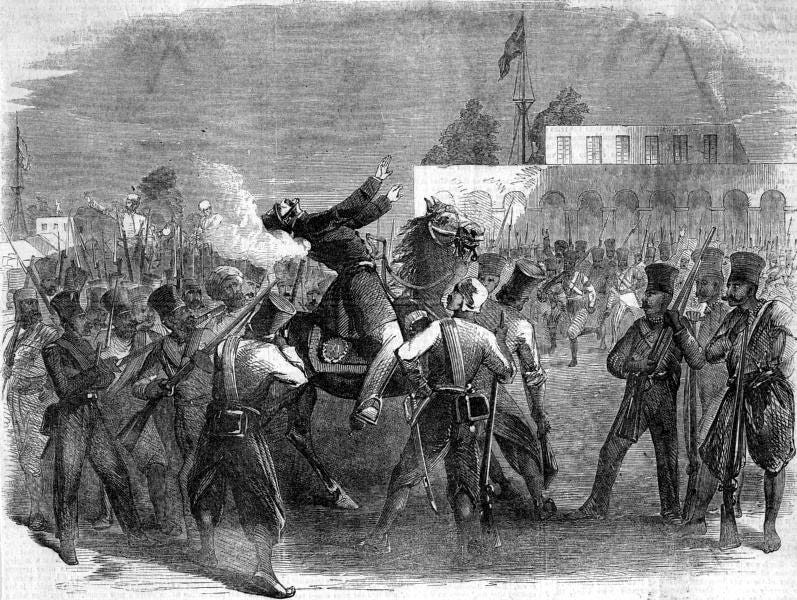

13. Meerut

‘Jack Sepoy may be able to cut down defenceless people but he can’t stand up to real pluck.’

Burlton tells Fleury about the mutiny at Meerut. Forty miles from Dehli and five hundred miles from Krishnapur, Meerut had one the largest cantonments (military stations) with 2,357 Indian sepoys and 2,038 British soldiers. On 9 May, a group of Indian soldiers were court-martialed and imprisoned for refusing the new cartridges.

The next day, the garrison mutinied, and Colonel John Finnis became the first British officer to be killed during the rebellion. The mutineers took up the slogan ‘Let's march to Delhi!’ and set off to the ancient city to declare the Mughal ruler, Bahadur Shah Zafar, Emperor of Hindustan.

‘What beats me, Rayne, is how the blessed natives got to hear of it before I did.’

There is no telegraph, and Rayne thinks the railway will never reach Krishnapur. But Fleury wonders about the speed those chapatis spread across the countryside.

14. The Giaour

'"That every woe a tear can claim, Except an erring sister's shame"'

Ford quotes from Lord Bryon’s The Giaour (1813), a poem of Romantic Orientalism. Subtitled ‘A Fragment of a Turkish Tale’, the epic poem tells of a slave, Leila, who falls in love with an infidel, ‘the giaour’, and is murdered by her master, Hassan.

15. John Keble and the Oxford Movement

‘It’s only possible for a man to believe in his own way, Mr Hopkins.’

The Collector reads some verses from his wife’s copy of John Keble’s The Christian Year, one of the most popular books of verse in the nineteenth century. Keble was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement in the Anglican Church. These argued for Tractarianism, the return to many Catholic beliefs and traditions within the English church. In the previous chapter, we learned that Krishnapur’s pastor, Reverand Hampton, had stuck to rowing in Oxford, keeping himself out of the theological debates between High and Low Church.

Footnote: What was the Oxford Movement?

What an odd creature, the Collector is! He keeps his children in velvet, flannel and wool, despite the hot climate; and he reads his daughter’s diaries so as to supervise their lives. ‘As any right-thinking father would.’ But then the children enter, the youngest shrinks away from her father, ‘back in the ayah’s skirts.’ It is an illuminating incident that Dr McNab pretends not to notice.

16. ‘It’s just not cricket’

'The cricket match may be only a stratagem, a means of not arousing suspicion.'

Wherever they went, the British brought cricket. In 1792, the Old Etonians toured India and played a match against the Calcutta Cricket Club, the oldest club in India. Cricket was seen as a way of introducing perceived British values and norms, as well as giving idle military units something to do.

As the General arrives swinging a cricket bat, the Collector and the Magistrate feel this is no time for games.

Except, apparently, there is time for a spot of croquet. As tensions rise, the British divide into the ‘confident’ and ‘nervous’ parties, with the majority voting for one course or the other, and occasionally both: ‘a calm and confident bolting to the Residency.’ Fleury feels like bolting but looks placidly confident.

And the Collector democratically embodies both sentiments by building a fortifying wall under the pretext of shading the croquet lawn. It is ‘his duty’ to win ‘game after game’ against his poor, overdressed ‘swooning daughters.’

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will be reading Chapters 5 and 6 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

Fleury reminds me of Pierre, in W&P?

Bhairava: (I’m not South Asian, but was married to one, and lived with him in Chennai, formerly called Madras, for many years). Bhairava’s name means terrifying, he looks terrifying, eager for blood. He has a baffling number of arms. His cup is made from a skull. There are jackals, carrion eaters near his shrine. He is often a gatekeeper, stationed at the entrance to temples to keep out evil-doers. I would have thought that he belonged at the place where Fleury goes to meet the Maharaja, and that he would symbolize Fleury’s transition from his idea of order into the disturbingly alien native world. (See the cave in Passsage to India?) Instead, Bhairava is placed at the entrance to a scene of the worst of the Raj - stupid, ugly, violent people who despise and demean Indians. He appears to represent them, instead of repelling them. Bhairava also has an association with Kali Yuga, the last and most degraded age of the universe, before it is destroyed and begins again. Could that be it? I’m interested in what others have to say.