Main Page | Reading Schedule | Online Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

An adventure in footnotes and tangents

This is an experiment. Until now, I have chosen beloved books for my read alongs. War and Peace and Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy have been my companions for many years. The slow reads are the flowering of my enthusiasm for these novels.

This year, I have chosen to explore three books I know very little about: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower, and JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur.

In selecting unfamiliar novels, I am embarking on an experiment in footnotes and tangents. What will happen when we apply our slow, creative and curious reading to these three books?

These posts are the rough draft, the first test results from the lab. What follows may not be as polished as my posts on Tolstoy and Mantel. But I hope you will find them interesting nonetheless.

Why The Siege of Krishnapur?

The three books I picked this year have two things in common. They are all historical novels, and they all come recommended by Hilary Mantel. Mantel described The Siege of Krishnapur as:

An idiosyncratic masterpiece, wise and richly comic, set in India in 1857 in a besieged town garrisoned by the British. Original and endlessly entertaining, it repays repeated readings.

James Gordon Farrell was born in Liverpool in 1935. His family were of Irish descent, and after World War II, the Farrells moved to Dublin. He studied at Oxford, where he contracted polio and spent time in an iron lung respirator tank – an experience he fictionalised in his early work, The Lung (1965).

As an author, James styled himself as JG Farrell, to distinguish himself from the far more widely known American writer, James T Farrell. In 1966, he began a Harkness Fellowship in the United States, embarking on a project to write about ‘people trying to adjust themselves to abrupt changes in their civilisation.’

The results were three distinct novels, often referred to as the Empire Trilogy for their common concern for British colonialism. Troubles (1970) is set during the 1919 Irish War of Independence, and retrospectively won the 1970 Booker Prize in a public vote in 2010. The Siege of Krishnapur won the Booker in 1973, and was followed by The Singapore Grip in 1978.

Farrell drowned in an accident off County Cork in 1979. He was only 44. Salman Rushdie wrote:

Had he not sadly died so young, there is no question that he would today be one of the really major novelists of the English language. The three novels that he did leave are all in their different way extraordinary.

Based on a true story

Krishnapur is a fictional town in northern India. The events of the novel are inspired by the siege of Lucknow during the Indian rebellion against the British East India Company in 1857. The uprising marked a turning point in British colonialism in the subcontinent: the East India Company was replaced by direct rule by the British Crown.

Names and titles are important. The British described the rebellion as a ‘mutiny’ among the Company’s Indian soldiers (‘sepoys’). However, support for the mutineers extended beyond the army, and its greater historical significance led many Indians to refer to the uprising as the First War of Independence. India finally won freedom from British rule in 1947.

During the rebellion, the British were besieged in the colonial Residency at Lucknow. Farrell has based his fictional siege on letters and memoirs from Lucknow, many of which you can read online:

A Diary Kept by Mrs. R. C. Germon, at Lucknow, between the months of May and December 1857

A Memoir, Letters and Diary of the Rev. Henry S. Polehampton, M.A., Chaplain of Lucknow (includes his wife’s diary detailing events at Lucknow)

The Siege of Lucknow, A Diary, by Julia Selina, Lady Inglis, 1833-1904

Footnotes

1. Invisible Indians and the nature of civilisation

The surprising thing is that this plain is not quite deserted, as one might expect.

The opening image of The Siege is striking: an ancient cemetery, the ‘City of the Silent’, set amongst ‘a dreary ocean of bald earth’ on the road to Krishnapur. The narrator imagines the scene viewed by a traveller, who finds ‘no comfort here … nothing that a European might recognise as civilization.’

Viewpoint is everything. Right from the start, we are uncomfortably aware of our own poor grasp of the environment: a deserted plain that isn’t deserted; a city that isn’t a city.

We see an Indian at a distance. We cannot fathom where he is walking to or why. ‘One part looks quite as good as another.’ This ignorance of Indian lives is an idea running through The Siege. Indians appear invisible, or undifferentiated and inexplicable, to British residents who – whether from arrogance or apathy – show no interest in the people around them.

This fatal lack of curiosity had not always been the case. This week, I listened to William Dalrymple and Anita Anand talk about the rebellion on their Empire podcast. Dalrymple describes how eighteenth-century British residents were enamoured by Indian culture. This period is alluded to in The Siege in the abandoned bungalows, where British representatives ‘lived in magnificent style … in imitation of the native princes.’

By the 1850s, any respect or interest in Indian civilisation had dried up. The British no longer mixed with Indians and were convinced of their cultural superiority and role as bringers of civilisation and Christianity to a barbaric corner of the Earth.

But what is civilisation? Farrell dryly notes that it must have something to do with bricks (‘one gets nowhere at all without them’). The Collector believes in bringing ‘civilisation to the natives’ as ‘the Romans had done in Britain’: amassing a collection of European art and science at the Residency at Krishnapur.

George Fleury is less sure. He has been commissioned to write ‘a small volume describing the advances that civilisation had made in India under the Company’s rule.’ He considers the lascivious and gluttonous officers in the Botanical Gardens at Calcutta and the sweaty, suffocating galloppe at the town hall. He thinks how civilisation …

… must be something more than the fashions and customs of one country imported into another, or how it must be a superior view of mankind.

Earlier, he tells Doctor Dunstaple that civilisation ‘denatures man. Think of the mills and the furnaces.’ Instead, he imagines some ‘great, beneficial disease’ that appears entirely absent from British rule in India.

2. The East India Company

Although he had seven children, and was living in a country of high mortality for Europeans, he had not yet brought himself to make a will; an unfortunate lapse of his usually powerful sense of duty.

The first chapter is full of foreboding details. Abandoned bungalows, unexplained chapatis, and an unwritten will. I learned from the Empire podcast, that it was compulsory for Company men to keep a will – a consequence of the lucrative but short-lived careers of the British in India.

In 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted a royal charter and trading monopoly to a group of London merchants, permitting them to trade in the ‘East Indies’. By the early nineteenth century, it was responsible for half the world’s trade and was ruling most of modern India.

It was the world’s largest company, with an army twice the size of the British army. Indians recruited into the Company’s army were called ‘sepoys’, an anglicised form of the Persian term for an infantry soldier in the Mughal Empire.

3. Queen Victoria’s bulging eyes

Victoria ascended the throne at the age of 18 in 1837 and ruled for 63 years and 216 days until her death in 1901. After the Indian Rebellion, the British deposed the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafarshe, and later installed Victoria as Empress of India.

On one of the lateral walls was a portrait of the young Queen with rather bulging blue eyes and a vigorous appearance.

Those bulging blue eyes follow the Collector out of the room to listen to the Magistrate extolling the wisdom of phrenology. The Magistrate is talking about the ‘bulging eyes’ of a fellow student of Franz Joseph Gall, a founder of the pseudoscience that claimed a link between bumps on the skull and mental traits.

Although it was initially concerned with human psychology, phrenology later became a justification for scientific racism and the categorisation of colonial subjects. For example, Belgian colonizers in East Africa would use phrenology to create an irreducible division between Hutus and Tutsis, creating the conditions for the Rwandan genocide.

Tangent: Phrenology and the Rwandan Genocide

Tangent: Django Unchained and the racist science of phrenology.

4. On Erl-kings and the Great Exhibition

‘And to be quite honest I consider that we’ve had far too many erl-kings in recent weeks, though I can assure you that even one erl king would be more than enough for me.’

The erl-king is a sinister child-killing elf or king of the fairies. He is a character in German romanticism, appearing in Herder’s ‘The Erlking's Daughter’ and Goethe's ‘Der Erlkönig’.

Jacob Grimm (of Brother Grimm fame) identified the word as originating with the Danish word (ellekonge) for ‘king of the elves.’ But there’s also another theory that connects the erl-king to Erlik Khan, the Turkic and Mongolian god of death.

Death stalks both these first chapters, from the ‘City of the Silent’ to Fleury’s visit to his mother’s grave in Calcutta. Fleury has cultivated an image as a romantic, ‘lurking around in graveyards’, only to discover that ‘the spirit of the times’ has moved on to poet Alfred Tennyson’s ‘great broad-shouldered, genial Englishman.’

Death is no longer sexy, but death will soon be the order of the day.

Back in Krishnapur, Miss Carpenter has composed a poem on the Collector’s favourite subject: the Great Exhibition. This was held in 1851 in Hyde Park, London: a spectacular presentation of culture and industry in a massive purpose-built glass house.

The Collector will have plenty to say about the Great Exhibition, so for now, we will leave it at that.

5. Hero Hearsey and Jack Sepoy

Fleury suspected himself of being a coward and here he was in the presence of the man who, in front of a sepoy quarter guard trembling on the brink of revolt, had ridden fearlessly up to the rebel who had just shot the adjutant.

The introduction of pre-greased cartridges for the new Enfield rifles was the spark that set off the Sepoy mutiny. Soldiers had to ‘bite the bullet’ to prepare the ammunition, and the rumour spread that the grease was pork or beef fat.

In The Siege, Captain Hudson gives us an account of the initial mutiny at Barrackpore. He says, ‘General Hearsey handled things pretty skilfully, even though some people thought he should have been more severe.’

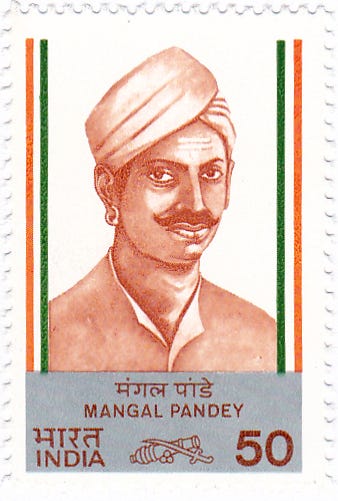

On the parade ground, an Indian soldier, Mangal Pandey, had attempted to incite an insurrection. His commander, Jemadar Ishwari Prasad, refused to arrest him, and both men were hanged. The regiment was disbanded. In the next few months, unrest spread to other regiments.

Thank you

As always is the case with these posts, I have run out of time. There are plenty more rabbit holes to explore in these two chapters, from the Royal Botanic Gardens of Calcutta to the South Part Street Cemetery. How do you prepare Moselle cup and what is a ‘Tweedside’ lounging jacket?

Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments. What did you make of these two opening chapters?

And I will be back next week when we will be reading Chapters 3 and 4 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

We have begun uploading additional resources for the read-along here: https://footnotesandtangents.substack.com/p/the-siege-of-krishnapur-online-resources

I'll try to add other people's recommendations along the way.

As a happy, (mostly lurking) 2024 War and Peace participant, I am thrilled to be participating in this new slow read.

Your comment about the British referring to the Lucknow uprising as the "Indian Mutiny," while the Indians referred to the same event as the "First War of Independence" reminds me of the different names for the American Civil War, depending on which side of the conflict one was on. The Northerners called it "The War of Southern Secession;" the Southerners "The War of Northern Aggression. Names DO matter.