📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for War and Peace 2024.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 42 of War and Peace 2024

This week, we have read Book 4, Part 2, Chapters 10–16.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

Are you enjoying our slow read? I need your help!

In November, I will launch the 2025 slow read of War and Peace. If you have enjoyed reading with us this year, I would love to hear from you. Your feedback will be enormously helpful for new readers deciding whether to join us in 2025. What were your expectations? What was your experience of reading slowly as part of a group? What surprised you? And would you recommend this slow read? If you are happy for me to share your thoughts with future readers, I have started a chat thread for testimonials, or you can send me a DM or email. Thank you so much for your time.

This week’s theme: Happy Feet

Once upon a time, I stood on a snake.1

The snake bit my foot, and my foot swelled up. The poison went to war on my blood, and though my blood would win, I was a few weeks mending, in hospital, in bed, and in a house above the clouds.

The house was in Ecuador, and the clouds were a forest. I was looking for peace, and I found Pierre.

Pierre Bezukhov. I had brought the biggest book I could find, six thousand miles across jungle and sea. It was 2007, and I was reading War and Peace for the first time.

Can fictional characters become friends?

This bumbling bear of a man was mine. He was a little older, but none the wiser. He was searching, and so was I. We were both lost in the world.

Like Pierre, I got angry. At others, but mostly myself. At my own foolishness and thoughts, running like horses in different directions.

I read War and Peace when I couldn't walk. My useless foot, bandaged up in bed. I was angry at myself, the snake and the universe for putting me there; and not thankful enough that I was still there at all.

Pierre is still here. He survived a duel, the deadliest battle in history, and a fire that consumed all Moscow. They locked him up and put him in front of a firing squad. He survived that too.

A prisoner of war, he considers his feet. He's lost his shoes – stolen or given away, he doesn't say. They are gone, which is bad timing if the French take him marching out of Russia. No wonder his new mentor, Platon, is busy gathering linen to bind their feet.

Pierre's not a practical man (neither am I). He's admiring his big dirty toes. His eyes are calm and resolute, like never before.

He shouldn't be happy. He's lost his freedom, his friends and his country. But here beneath him are two feet and ten toes. His body. His life. The thing he is. He looks at a lavender dog who knows something most of us forget.

He searched and searched for life's meaning. In mysteries and great men. In struggle and self-improvement. But the truth was always there beneath him. The universe and his two feet.

‘All that is me, all that is within me, and it is all I.’

Chapter 10: The Wounded Animal

All of Napoleon’s measures, efforts and plans proved worthless. Nothing happened in the way Napoleon intended, and he received reports of continuing disorder and looting. News of the battle of Tarutino caused the French to panic and, like a wounded animal, rush at their attacker and then flee down a dangerous path, ‘where the old scent was familiar.’

Napoleon’s treasure

Bonaparte was responsible for the extensive looting and theft of artworks and precious objects from Europe, Egypt and the Middle East. In Italy, the seizures were systematic, and a special commission was responsible for selecting artefacts for confiscation. Revolutionary France justified this theft based on the rights of conquest and the Enlightenment ideals of creating an encyclopedic collection of art, culture and knowledge.

After Napoleon’s abdication, the Congress of Vienna ordered the restitution of most of this art. However, this agreement excluded Egyptian artefacts that Britain had seized from the French after the Battle of the Nile in 1798, including the Rosetta Stone which is still held in the British Museum.

Napoleon’s Grande Armée reputedly stole 80 tonnes of treasure from Moscow and buried it en route in a hidden location in modern-day Belarus. A member of Napoleon’s staff said the treasure was dumped in Lake Semlevo near Smolensk, but no gold has ever been found.

Further reading:

Chapter 11: Happy Feet

During the French occupation of Moscow, Pierre lived in his shed with Karataev and the other prisoners. He has grown a beard and lost his shoes. The army will soon leave the city, and the soldiers have given boot leather and linen to the prisoners to make shoes and shirts. Platon gives a Frenchman a shirt he has sewn, and the chastened soldier lets him keep the scraps to make foot wrappings.

Every time he looked at his bare feet a smile of animated self-satisfaction flitted across his face. The sight of them reminded him of all he had experienced and learned during these weeks, and this recollection was pleasant to him.

It's good to see you, Pierre. And looking so well, in your rags. What happened to your shoes? I get the feeling you gave them away, or more likely, they were taken by a prison guard contemplating the long march home.

It's a long way to anywhere from here, and not a good time to be barefoot. They are making shoes for the soldiers, but I'd be worried about your own feet.

Platon's got them covered. He's not just sage sayings; he's got his thinking cap on.

Thankfully, the Frenchman can see that the scraps of linen are more use to Pierre and Platon than they are to him.

Oh, and let's not forget the blue-grey dog. Another animal with a glorious walk-on part in this novel.

Its lack of a master, a name, and even of a breed or any definite colour, did not seem to trouble the blue-grey dog in the least. Its furry tail stood up firm and round as a plume, its bandy legs served it so well that it would often gracefully lift a hind leg and run very easily and quickly on three legs, as if disdaining to use all four. Everything pleased it.

Why do we befriend animals? Perhaps to catch a sniff of this canine wisdom. For when you’re in a tight spot, it’s good to remember that it’s a dog’s life.

What lessons have you learned from an animal close to you?

Chapter 12: Peace At Last

In those four weeks, Pierre found the tranquillity he had long sought. The restriction of his freedom clarified his needs and made his past concerns appear ridiculous, trivial and amusing. In his previous life, his strength and simplicity had been harmful to him. But among the prisoners and guards, he found himself respected and liked.

He had long sought in different ways that tranquillity of mind, that inner harmony, which had so impressed him in the soldiers at the battle of Borodino.

The horror of death (the executions), his captivity, and the example of Platon are the three causes of Pierre's new tranquillity.

It's peace at last for Pierre, for Tolstoy tells us that ‘for the rest of his life’, this month of captivity will comfort him. He will survive this ordeal and be able to draw on the experience in the future.

Our foolish friend has become a ‘hero,’ admired by those around him. His size, strength, and simplicity no longer make him feel shameful and self-conscious. They are who he is and the only things no one can take away from him.

What has Pierre learned?

Have you ever experienced something similar in your life?

Barefoot Philosophers

Ilya Repin’s painting of Leo Tolstoy barefoot took ten years to complete and depicts the writer as a simple peasant on his land at Yasnaya Polyana. This is the Tolstoy of 1901, the world-famous Christian Anarchist who renounced his title and his own works of literature, including War and Peace.

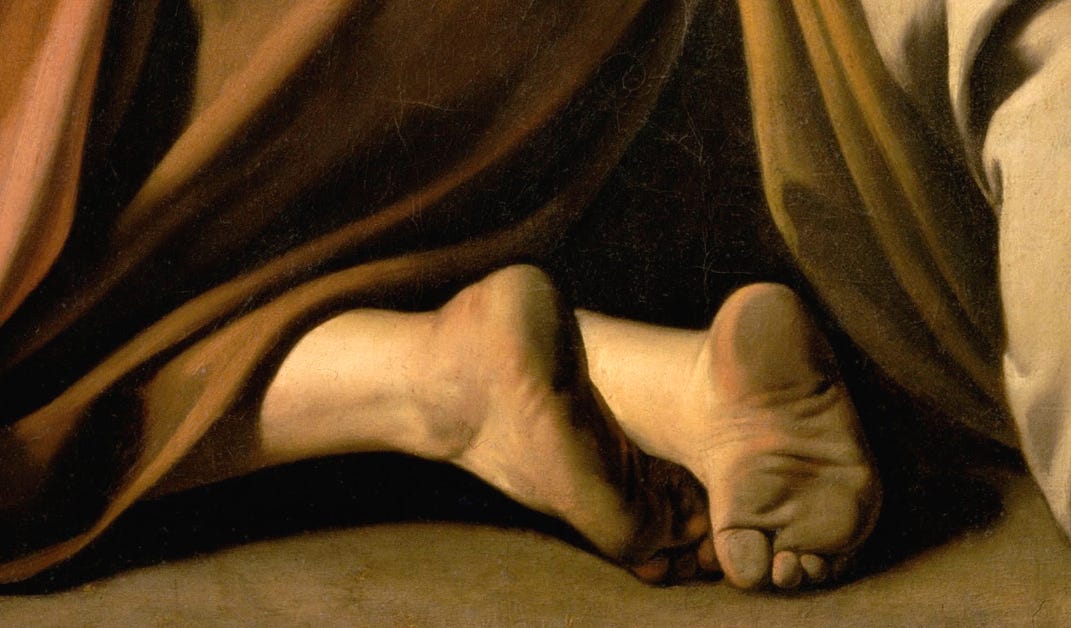

We are troubled by our feet. They are the lowest part of our body, the furthest from the lofty thoughts in our heads, and those even loftier ideals of the infinite heavens. The painter Caravaggio got into a lot of trouble with the Catholic Church for his dirty-footed saints. Feet are symbols of poverty, labour and our animal selves.

The anthropologist Tim Ingold wrote about the attempt in Western culture to become ‘groundless’ and escape our ancestry as four-legged beasts. As we evolved to stand upright, we gained the free use of our hands to hold and make tools. Civilisation was the achievement of head and hands.

Man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands.

So something lacking in inspiration or excitement is pedestrian. In German, the plebs are fussvolk, foot-people; from the sedan chair to the automobile, social and cultural superiority is signified by getting places without touching the ground.

Pierre’s feet are a rejection of all of this, as is his identification with a stray dog play-biting him outside his shed in Moscow. We are earthly beasts before we are saints and angels, and it is our feet that connect us to the universe.

Further reading:

Chapter 13: Marching Orders

The French leave Moscow with their prisoners of war. Pierre tries to get help for the sick man Sokolov, but he realises the mysterious force that makes men kill each other has once again taken hold of the French. Pierre is put with the officer-prisoners, and they march through the ruins and out of the city, past a dead man smeared with soot.

In the corporal's changed face, in the sound of his voice, in the stirring and deafening noise of the drums, he recognized that mysterious, callous force which compelled people against their will to kill their fellow-men.

Only yesterday, they were looking out for each other. Shirts for money and foot-wrappings.

But what an effect those metal straps have on the soldiers. A lot of angry scowls and curses and very little sympathy for a dying man.

It's not that the French are cruel by nature, or as Platon said, ‘People said they were not Christian.’ But when circumstances change, people behave differently. Human feeling can be as momentary as Davout’s look at Pierre, before he issued the death sentence.

Tolstoy encapsulates hope and despair in this: there is the possibility of compassion everywhere, but for how long? Long enough to save you?

What is the ‘mysterious force’ that takes hold of the French soldiers?

How do you think Pierre’s experience differs from the other officer-prisoners?

Chapter 14: The Immortal Soul

They leave Moscow. The prisoners marvel at the evacuating army, weighed down by loot. They are given their first rations of horse-flesh and are told they will be shot if they lag behind. Pierre attempts to talk to the common soldier-prisoners but is stopped. Down beside a cart, he laughs at the absurdity of his position and the futility of trying to capture something as infinite as a soul.

And all that is me, all that is within me, and is all I. And they caught all that and put it into a shed boarded up with planks.

Andrei saw the infinite lofty skies above Austerlitz, but could not reach them and bring them within him. Pierre does what Andrei failed to do. So when someone tells him to turn back, what can he do but laugh? You can't pin down an immortal soul, nor separate it from the infinite universe.

How do you interpret Pierre’s laughter?

Chapter 15: A Quiet Little General

After Tarutino, an opportunity presents itself for another battle. Kutuzov overrules his generals but sends a skirmishing party under General Dokhturov. Tolstoy really likes Dokhturov. Near Forminsk, they learn that the entire French army is there with Napoleon. The cautious Dokhturov refuses to engage and reports back to Kutuzov for further instructions.

And this silence about Dokhturov is the clearest testimony to his merit.

Dokhturov: Not to be confused with Dorokhov's guerrilla detachment, or bad boy Dolokhov. And definitely not Denisov. Where is Denisov?

Tolstoy doesn't praise generals much, so he must really like Dokhturov to give him a whole chapter of kind words. The infantry general is the ‘small connecting cog-wheel which revolves quietly’ and ‘is one of the most essential parts of the machine.’ He was the last general in the rearguard at Austerlitz, rescuing 8,000 men and leaving the artillery behind.

What does Tolstoy like about this little general? No theatrics, he just gets on with the job. He sounds very good, Leo, but perhaps a tiny bit dull.

Chapter 16: Wake The General

Dokhturov’s messenger reaches headquarters in the middle of the night. He convinces the orderly to wake General Konovnitsyn, another of Tolstoy’s favourite ‘unnoticed cog-wheels’ ignored by posterity. Konovnitsyn wearily goes off to report to ‘the nest of influential men’ who will inevitably be stirred up by the news.

There's nothing to be done, we'll have to wake him.

Another chapter, another general that Tolstoy likes. It's like waiting for a bus.

In this chapter, the cockroaches and candlesticks give me the creeps. It's one of those marvellous little chapters where we hardly know any of the characters, yet the scene is so vivid. Evocative of a dark, autumn night, like tonight.

Can you relate in anyway to Konovnitsyn? Either as the ‘unnoticed cog-wheel’ or the weary messenger who can foresee the inevitable argument.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

And that’s all for this week. I love to read your thoughts in the comments and the chat threads. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

I find it interesting how you came to War and Peace and the impact it has had on you, essentially I guess that snake bite lead you to Footnotes and Tangents (an apt name). I am amazed that I myself am looking to re-read it next year again as part of the slow read, but there is so much to it, it has to be done.

When you ask what we have learned from animals, we have a few animals but my biggest lessons are always from my chestnut mare. Humans talk about "breaking in" horses and I have always hated this term. Why would you want to break the spirit of another creature when it is so much more fulfilling and enduring to work with them and learn from them. Poppy does not tolerate anything that causes her upset or pain and I respect her for that. She picks up when I am in-tolerate, stressed, anxious and makes me pay attention to myself by only fully engaging when I have settled my mind and offer her calm and patience and time.

Pierre's grounding in these chapters had been literal in respect of his feet fully engaging with the earth, and metaphorical in respect of his mind settling. I can understand why you came to befriend him and I do think we can befriend characters in books, from childhood onwards these are the characters that stay always with us.

I found it very hard to read the war chapters, since I kept thinking about Ukraine, so I haven't kept up. I will sign up for the next round. I have enjoyed reading all the commentary!