Oysters for the Creative Reader

Friday Fireside #9 | A celebration of wild and weird readings of great books

Dear reader,

“Now the world is your oyster.”

The first books I read independently were the Dragon Pirate Stories by Sheila K McCullagh. These were graded readers that began by introducing three pirates: Benjamin the Blue, Roger the Red, and Gregory the Green. As the series progressed, the language and plot became more complex. I remember a dragon and merfolk, witches and a magic whistle.

I have a memory of finishing these books and returning them to the school library. Someone, I assume my mum, is saying to me: “now the world is your oyster.”

What is peculiar about this memory is I see myself from a distance, on the other side of a large room. I am small, and the books are smaller, and the space beyond seems implausibly vast. This makes me suspect it is a false memory, or the reconstruction of one by things told to me, long ago.

Whether it is real or not is immaterial: thirty-five years later, the memory has the weight of meaning and the form of an origin story for my adventures in reading.

“Now the world is your oyster.”

The idiom has lost its original meaning. Shakespeare meant it as a veiled threat in The Merry Wives of Windsor. John Falstaff refuses to lend money to Ancient Pistol, and the soldier replies: “Why then the world’s mine oyster, Which I with sword will open.” The shellfish is notoriously difficult to prise apart. But with something sharp, one can find not just food but secreted treasure: a pearl to make one’s fortune.

My mother did not intend to rob me at swordpoint. I believe what she meant was that I had reached a place where anything was possible. I had stumbled over every word, stitching a fine mesh of meaning between each sentence, its sounds and its place in the story. With this skill, hard-won, I opened libraries and greedily fed my thoughts.

“The unread story is not a story;” wrote Ursula K Le Guin, “it is little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live: a live thing, a story.”1

Reading is not just a means for acquiring knowledge and forming an understanding of the world. It is also a means to make meaning. It is a creative act.

I found in those pirate books many things the author didn’t put there. I read between the lines. Animated the illustrations in my head. The characters became a living thing that existed apart from the words. The memory of reading gained its own texture, a depth of colour and a layering of imagined places, far beyond anything envisaged by Sheila K McCullagh.

This is how it must be. A book appears to be a finished thing: the product of its time and the mind of its author in the moment of its creation. But as a reader, argued Angela Carta, “you bring your history and you read it in your own terms.” You re-write the book into your own thoughts, memory and imagination.2

This is the pearl in the oyster. “A book, properly written,” wrote Alan Garner, “is an invitation to the reader to enter: to join the writer in a creative act: the act of reading. A novel, it has been said, is a mechanism for generating interpretations. If interpretation is limited to what the writer “meant", the creative opportunity has been missed. Each reading should be a unique meeting, leading to a new interpretation.”3

This idea may frighten writers who cling to their stories. But it is a blessing and a gift, to create something so wild that it takes on a life of its own. Literary scholars and critics may attempt to instruct us on how to read and the correct way to interpret stories. But outside the classroom, they are unlikely to succeed. Reading is wild by nature. It can be caged, but never tamed. And each encounter with a book is unique, as the words lodge themselves into a new imagination, between memories and feelings foreign to the original story.

This year I brought together several hundred people to read Tolstoy’s War and Peace. A chapter a day. Along the way, we discussed Tolstoy’s beliefs and intentions and the social and cultural conditions of 19th-century Russia. Tolstoy’s subtle characterisation and less subtle theories on history helped us to better see and understand his world and our own.

But we did not miss the “creative opportunity” of generating further interpretations. Readers wondered about a repressed romance between Pierre and Andrei. They considered the sexuality of Marya Bolkonskaya and the neurodivergent personality of Vera Rostova. We wondered whether Nikolai passed into Fairyland, and what Sonya saw in the shed that Christmas. And more than any other character, we speculated endlessly on the hidden worlds within Helene Bezukhova.

We will not always like other reader’s interpretations. We may feel they’re downright wrong and have missed the point. But that is beside the point. These flights of fancy allow individual readers to engage with the novel on their own terms. They bring their history to the book, and the book offers them something in return. It is a hallowed exchange, alive with creative possibilities.

A story is a subversive thing, always working itself away from the intentions of its creator. I am sure the Dragon Pirate Stories were designed to aid comprehension. The world was my oyster because I could now read it. But in reading the world, I had gained the gift of re-making it. To re-tell it over and over, to myself, and anyone who may wish to listen.

And when I’m done telling what I’ve seen between the pages, I will want to shut up and listen to you. Listen to what you’ve seen and what you’ve felt. I’m sure it will be different, and we’ll make something new from that too.

Because from now on, the world is our oyster.

Thank you for reading,

Simon

Join my slow reads

Next year I will be hosting two separate book groups. Whisky and Perseverance will be the second year of reading War and Peace, a chapter a day. Wolf Crawl will be a slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. You can join either of these by turning on notifications here.

Next week’s Friday Fireside will be an introduction to the Wolf Crawl read along.

News…

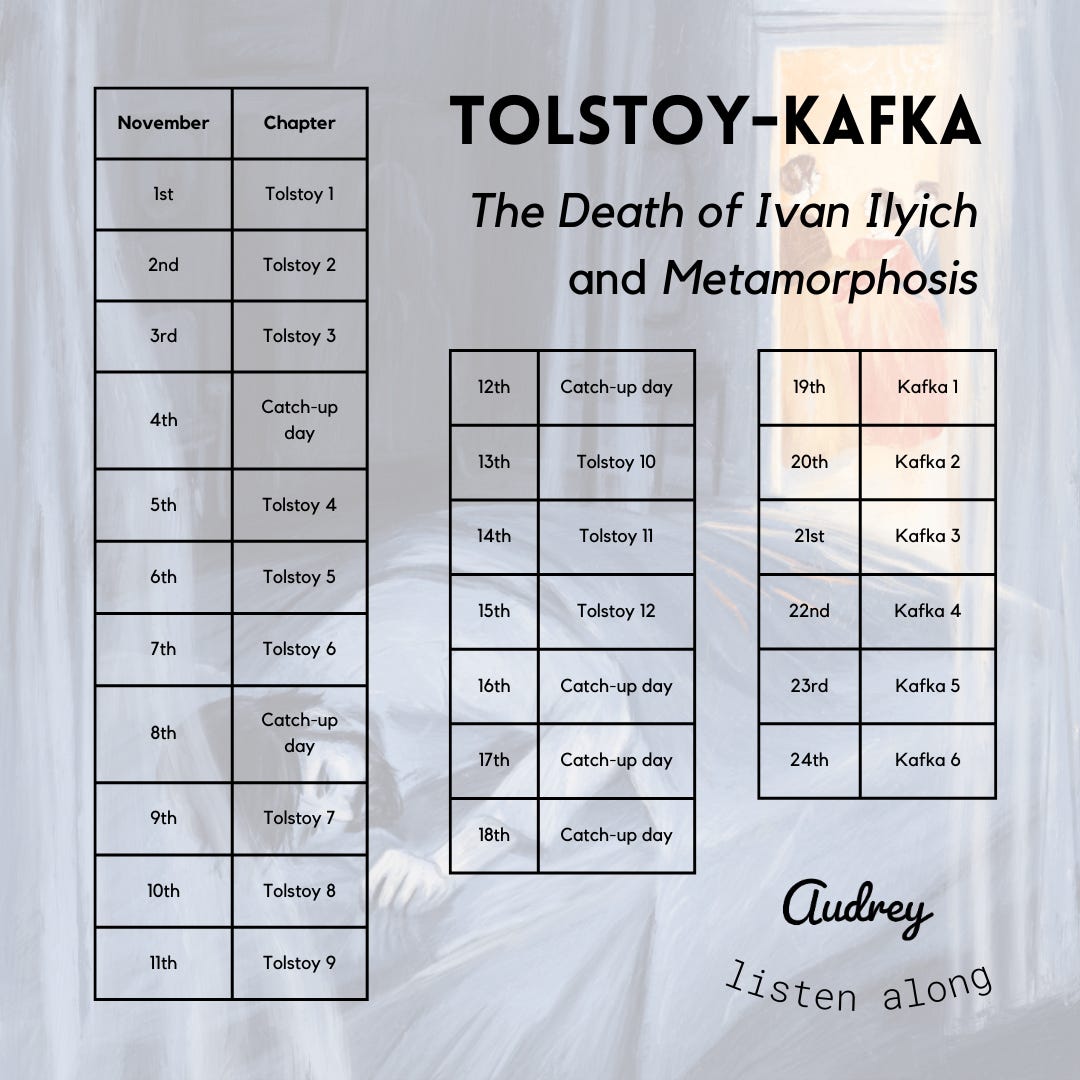

A reminder that Audrey is running a listen-along next month of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis. I had the great privilege of being the Audrey guide for both of these novellas, creating multi-media notes to accompany the audiobooks.

Sign up to the listen-along here. This is a great way to explore these books, and I heartily recommend it. The listen-along schedule looks like this:

In case you missed it…

Here’s the most recent War and Peace post:

Happy Feet

First thoughts Once upon a time, I stood on a snake. The snake bit my foot and my foot swelled up. The poison went to war on my blood and though my blood would win, I was a few weeks mending, in hospital, in bed, and in a house above the clouds. The house was in Ecuador and the clouds were a forest. I was looking for peace and I found Pierre.

Choose your own adventure

You have been reading a Friday Fireside letter from me,

. You can pick and mix which letters you want to receive by turning on and off notifications on your manage subscription page. By default, you won’t receive read-along updates unless you choose to join one of them.From the author’s essay, “Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?”. There is some interesting discussion on this piece by Maria Popova here. In the same piece, Le Guin argues:

“Writers have to get used to launching something beautiful and watching it crash and burn. They also have to learn when to let go of control, when the work takes off on its own and flies, farther than they ever planned or imagined, to places they didn’t know they knew. All makers must leave room for the acts of the spirit.”

From Alan Garner’s The Voice That Thunders. The British author’s most recent book, Treacle Walker, was shortlisted for The Booker Prize. It is an exceptional read and rewards careful re-reading.

What a very wise piece, brimful of possibilities. Love the memory of ‘the world of books’ being unlocked for you. And what a rich gathering of quotes. Put me in mind of “A writer only begins a book. A reader finishes it”. Samuel Johnson, Works of Samuel Johnson

More fabulous words, Simon, thank you.

So many delightful morsels of wisdom about books and reading here 😁 and we will make our first fire of the season tonight!