📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for War and Peace 2024.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 45 of War and Peace 2024

This week, we have read Book 4, Part 3, Chapters 12 – 18.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

Are you enjoying our slow read? I need your help!

This month, I will launch the 2025 slow read of War and Peace. If you have enjoyed reading with us this year, I would love to hear from you. Your feedback will be enormously helpful for new readers deciding whether to join us in 2025. What were your expectations? What was your experience of reading slowly as part of a group? What surprised you? And would you recommend this slow read? If you are happy for me to share your thoughts with future readers, I have started a chat thread for testimonials, or you can send me a DM or email. Thank you so much for your time.

This week’s theme: The Drowned and the Saved

This week, Tolstoy reminds us again that characters do not exist to please us, or entertain. We are not their judge but an imperfect friend, struggling to understand.

Because: How hard it is to imagine Pierre’s suffering. I’d put myself in his shoes, but those happy feet are bare and bleeding now. As the transport moves west, two-thirds of his fellow prisoners melt like snow or are shot on the roadside. Lice cover his body, horseflesh on his tongue, seasoned with gunpowder.

But here on this road of misery, he thinks: ‘There is nothing in the world that is terrible.’ With the right frame of mind, one can endure the pains of this world, and perhaps even find comfort and beauty in them.

Meanwhile, his friend and mentor is falling. Platon has given up. He puts his fate in God and, without grumbling, hopes for death.

Pierre hardly notices. Worse, ‘his feeling of pity for this man frightened him,’ and he does not look back when the bullet comes.

If this seems callous or self-absorbed, perhaps it is. But Pierre is in survival mode, and Platon’s despair and fatalism are infectious. And his story of a merchant’s exile is his way of saying goodbye.

But Pierre loves life. So he buries himself deep in memories and hardens himself to the pain all around. It’s not hard to relate to this picture. Pierre seems to stand for all of us in our days of dread: Frightened of what might happen if we let ourselves feel too much.

These chapters always remind me of Primo Levi’s words in the last book he wrote: The Drowned and the Saved. The Italian chemist and writer survived Auschwitz but could not survive the guilt. He wrote that, ‘the prisoners who saved themselves were not the best.’ They were ‘the selfish, the violent, the insensitive.’

Pierre and Primo are not ‘bearers of a message’ from the abyss. They are poor witnesses, averting their gaze. It is Platon’s story that tells us what it is like to reach the end of the road, not Pierre’s. Like Andrei’s visions, Platon’s merchant tale is illegible to the living, because it means most to those closer to death than to life.

Pierre’s story makes more sense to us, because it embodies the shame of those who survive. He survived the worst. But, as Primo Levi wrote, ‘the best are all dead.’

Chapter 12: Pierre’s Philosophy

We wind back the clock to before Pierre’s rescue. Of the 330 prisoners in the convoy, fewer than 100 remain. Pierre is reunited with Platon and the grey-blue dog. Karataev falls ill and Pierre keeps his distance, although he does not know why. Bezukhov discovers he can endure any discomfort. He ignores the state of his feet and the inevitable fate of Platon, keeps walking and stays happy.

He has learned that, as there is no condition in which man can be happy and entirely free, so there is no condition in which he need be unhappy and not free.

His fellow prisoners are shot, his feet are falling apart, lice devour him; he survives on a diet of horseflesh seasoned with gunpowder.

Yet in this horror, he concludes there is nothing ‘terrible’ in this world, because suffering is not something that happens to us, but something we do to ourselves.

What are we to make of this? It hardens him to the horrors around him, and makes him heartless towards his fellow prisoners, but it has allowed him to survive these hard weeks.

What is your response to Pierre’s current state of mind? How do you make sense of it? And is he right?

Chapter 13: A Merchant’s Tale

Pierre walks, counting his steps, thinking of the tale Platon told the previous day. It was the story of a rich merchant who had been wrongly punished for a murder he did not commit. Many years later, imprisoned in Siberia, he meets the real murderer who begs forgiveness. The miscarriage of injustice is brought to the attention of the Tsar, who frees the merchant. But before this can be done, ‘God had already forgiven him’ for the merchant had died. Pierre is moved less by the story and more by the manner in which Platon tells it.

His feeling of pity for this man frightened him and he wished to go away, but there was no other fire, and Pierre sat down, trying not to look at Platon.

What do you think about Platon’s story?

Tolstoy later reworked it into the short story God Sees the Truth, But Waits. It is a tale of earthly and divine forgiveness. In the longer version, the merchant wrongly accused of murder is called Aksionov, and the true murderer is Semyonich. Both are exiled to Siberia for crimes they didn’t commit. Semyonich confesses to Aksionov, but the merchant says: ‘God will forgive you! … Maybe I am a hundred times worse than you.’

With those words, ‘his heart grew light’, and he wished only for his death. And before the order comes for his release, he is already dead.

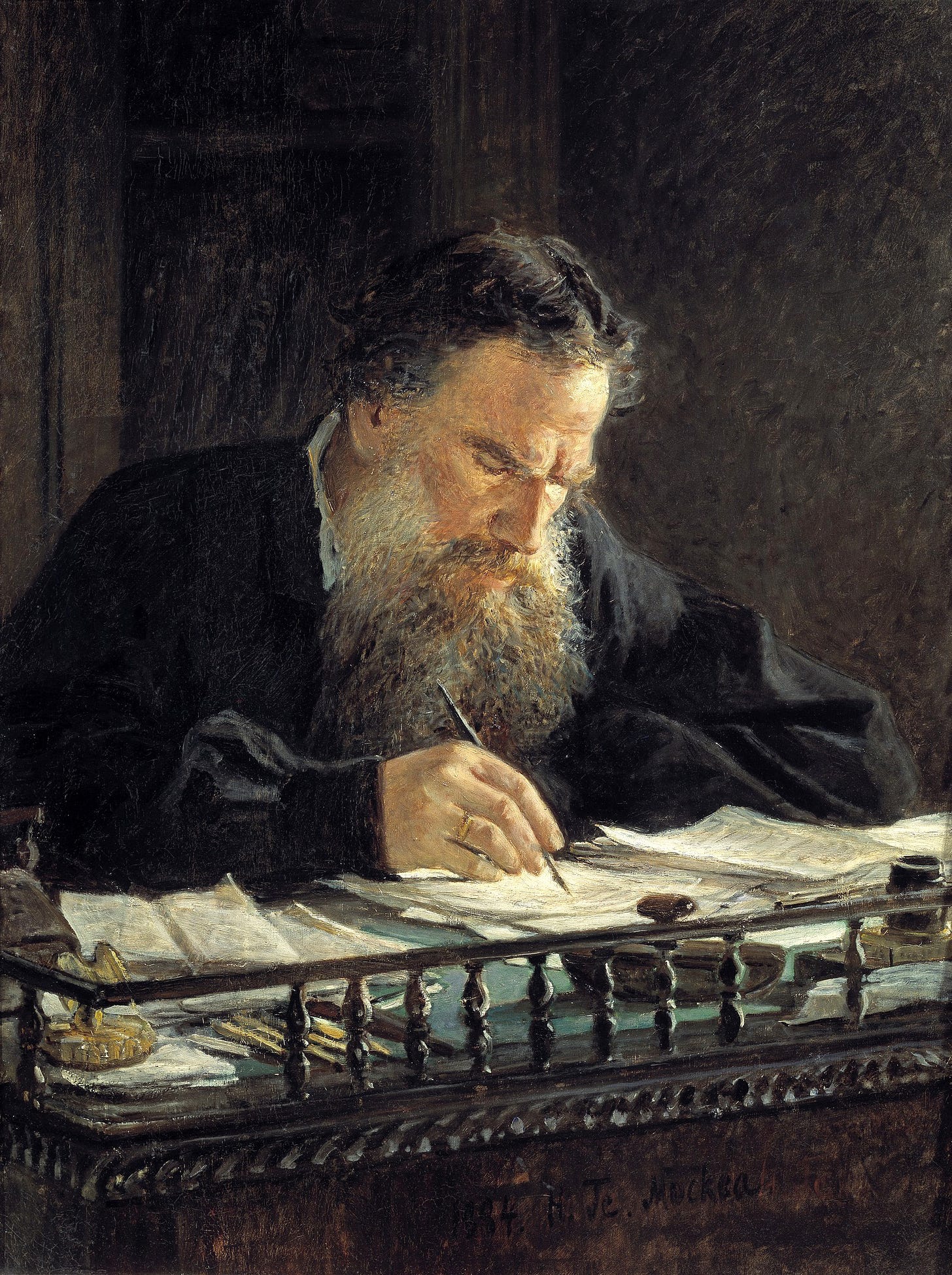

In 1897, Leo Tolstoy wrote What is Art? His answer to this question is influenced by his radical Christianity, dismissing great swathes of art, music and literature for lacking the sincerity, simplicity and ethical foundations of great art. He consigns most of his own work to the ‘category of bad art,’ including War and Peace.

He saves two stories: The Prisoner of the Caucasus and God Sees the Truth, But Waits.

At first glance, Platon’s story appears to be asking, why do bad things happen to good people? How can there be any justice in the world, when a good man loses everything for a crime he didn’t commit?

But the ‘truth’ that ‘God sees’ is that no one is without sin. I may be ‘a hundred times worse than you’, and we cannot fully understand this divine justice. A miscarriage of justice and a wasted life are of little weight compared to eternity.

I don’t know how I feel about this story. It provides a consoling narrative for Pierre and Platon with which to understand their great suffering. Suffering they surely do not deserve. It creates a sense of peace in Aksionov, Platon and Pierre. Aksionov loses the desire to go home, Platon loses the desire to live.

Now, Aksionov believes his wife is dead, and his children have forgotten him. Life for Platon holds little joy and much pain. Death is a form of peace and divine forgiveness.

And Pierre?

Pierre’s soul was dimly but joyfully filled not by the story itself but by its mysterious significance: by the raptuous joy that lit up Karataev’s face as he told it, and the mystic significance of that joy.

I think this joy has something to do with losing the fear of death. ‘Love of death’ was one of the seven virtues of the Freemasons. The one Pierre immediately forgot, because he loves life. It is one of the most attractive aspects of his character. I think he can see the wisdom in this story, but he is unable to fully understand it. And for the moment, I am quite glad that he does not.

What do you think?

Further reading:

Chapter 14: Sympathies

A marshal rides past in a carriage. Pierre thinks he sees a concealed look of sympathy on the general’s face. He sees Platon, leaning against a birch tree. The man seems to want to talk to Pierre, but Pierre walks away. Behind him, Platon is shot and killed. The blue-grey dog howls and Pierre notices on the soldiers’ faces the same expression he had seen at the execution.

On his face, besides the look of joyful emotion it has worn yesterday while telling the tale of the merchant who suffered innocently, there was now an expression of quiet solemnity.

The marshal, flying past the prisoners in his carriage, tries to conceal his sympathy for Pierre. Pierre, seeing that Platon wants to speak with him, moves hastily away.

How we protect ourselves from the pain of others.

Only the lavender dog knows how to grieve a man who can go no further.

Its howl is an echo of Denisov's dog-like yelp over Rostov's body. Because Denisov, who's seen enough men die, does not armour his heart as the marshal and Pierre do.

I wonder whether Platon’s story was his way of saying goodbye. It was never him to grumble or get angry. He found a way to accept his suffering. Then one day, he just stopped walking.

Tolstoy’s fascination with death

In Mary Beard’s introduction to The Death of Ivan Ilyich she writes about Tolstoy’s lifelong curiosity and obsession with death and dying. He was especially interested in the creative challenge of describing an experience of which no one has first-hand knowledge. Until it is too late.

He reportedly asked his friends to quiz him on his own death as he was going through it. He even devised a code of eye movements in case he was unable to answer. In the end, no one put the questions to him.

We get a sense of him exploring the experience of death in Andrei’s visions and revelations. In the end, Andrei fades from the world of the living. He is there and not there, and then he is gone. Platon also seems to pass some threshold where life ceases to have meaning.

Pierre comes close to death three times: on the duelling ground, at his mock execution, and here on the road to Smolensk. He gains something from it. But his knowledge is distinct from that of Platon’s and Andrei’s. In The Death of Ivan Ilyich, the protagonist also crosses that threshold, cutting loose from the land of the living.

This leads me to think the reason I identify with Pierre is because I am alive. When Andrei (and Platon and Ivan Ilyich) cross that invisible line they are no longer intelligible to me. And in fact, I recoil from their acceptance of death. This does not mean they are wrong or there isn’t truth in what they see and say. But it is not a truth I am ready to accept.

However, I know that I will keep returning to these chapters and ideas, and see new things and ask new questions. I am only scratching the surface, and instinctively I know I will see these chapters differently in a time to come.

Chapter 15: This is Life

They stop at the village of Shamshevo. Pierre dreams of a liquid, vibrating globe: each drop representing a life trying to expand to reflect God, merging, submerging and re-emerging on the surface. Awake, he stops himself thinking of Platon by returning to his memories and imagination. The next day, they are rescued. Dolokhov counts the French prisoners and the Cossacks bury Petya Rostov.

And without linking up the events of the day or drawing a conclusion from them, Pierre closed his eyes, seeing a vision of the country in summer-time mingled with memories of bathing and of the liquid, vibrating globe, and he sank into water so that it closed over his head.

Pierre's last night of captivity. The same night that the other Pierre, Petya, was in fairyland. This Pierre is lost in memories real and imagined. He's deep within himself, until the lavender dog makes him remember Platon. As quickly as his heart opens, he closes it again around memories and sinks into past waters.

The water seems like an allusion to baptism, but he could just as well be drowning.

Dolokhov arrives too late for Platon. He saves the man he once tried to kill, and who almost killed him. But the ‘cruel light’ in his eyes tells us he is a man of his word. He will shoot the French prisoners. Pierre's fortune will be their bad luck.

Droplets on a globe, all trying to expand, and crushing each other as they do.

What is the significance of Pierre’s dream?

Of all the chapters in War and Peace, these four confound me the most. Every time I read them, I see things differently. I like this about them. Books that explain themselves are as dissatisfying as readers who are convinced of the correctness of their interpretation. My reading of War and Peace is always changing, like that vibrating globe.

What does Pierre’s globe mean? This is from Andrew Kaufman’s essay ‘The Dog and the Globe: Pierre’s Journey to the Truth’:

The dream of the globe appears at first to be an irrelevant diversion from what should be most important to Pierre in this moment—Karataev’s death. But upon further consideration we realize that there could hardly be a better tribute to Karataev’s memory than Pierre’s nonreaction to his execution. For what does Karataev represent, if not the futility of worldly striving and the necessity of total submission to the will of the world? Pierre’s nonreaction reveals that he indeed has internalized Karataev’s wisdom. Moreover, Pierre has not forgotten about Karataev. The peasant has become etched indelibly in his subconscious. He is one of the globe’s drops, which spread out and disappear and eventually reemerge. And so Karataev will reemerge, for months and years afterwards, as the leitmotif of Pierre’s calmer, wiser life. Though Pierre does not react to Karataev’s actual execution, he half-consciously knows that his mentor has died. In his dreamlike state Pierre therefore knows more than ordinary consciousness can provide him. He knows the whole truth about Karataev’s death. He intuitively knows that Karataev, although physically gone, will continue to be a presence in his world.

Chapter 16: Majesties

After 28 October, the frosts begin. The French army melts away. Napoleon’s chief of staff writes to the emperor to inform him of the desperate state of the army. And although the commanders continue to write each other flowery letters using their full titles, they all feel wretched and think only of saving themselves.

They all felt that they were miserable wretches who had done much evil, for which they had now to pay.

Dolokhov came for Pierre just in time. He wouldn't have survived as far as Smolensk.

It's every man for himself now. Winter is closing in, with the Cossacks not far behind. Calling yourself Majesty won't make a blind bit of difference.

The shadow of Napoleon

In this chapter, Louis-Alexandre Berthier sends a letter to the emperor informing him of the desperate state of the army. Historians remember him as an efficient administrator who opposed the rapid advance towards Moscow. When Napoleon ignored his prescient warnings, he reportedly burst into tears. Berthier was one of Napoleon’s most trusted and faithful servants and his chief of staff from the first campaign in Italy in 1796 until Napoleon’s abdication in 1814. In 1815, in suspicious circumstances, Berthier fell from a window to his death. Napoleon felt his abscene at the battle of Waterloo, writing later: ‘If Berthier had been there, I would not have met this misfortune.’

Further reading:

Chapter 17: Blindman’s Buff

The Russians pursue the French, occasionally running into one another on the road out of Russia. Napoleon’s army becomes increasingly desperate and disorganised and suffers substantial losses at the Battle of Krasnoi. Ney tries to blow up the Smolensk walls for no reason and is the last Frenchman out of Russia, crossing the Dnieper by night.

Trust Tolstoy to compare the destruction of an army to a parlour game. I can't remember the last time I played blindman's buff, but I don't remember it being this terrifying. This jarring metaphor reminds me of Nikolai Rostov, under fire at Schöngrabern, running ‘with the impetuosity he used to show at tag.’ The night before Borodino, Andrei railed against grown men who treat war like a game. The comparison underscores the senseless waste of it all.

The last Frenchman in Russia

Michel Ney had the unenviable command of the rearguard as the Grande Armée retreated through Russia. He was known as ‘the last Frenchman on Russian soil’ for leading the rearguard across the Niemen on 14 December. Napoleon called him ‘the bravest of the brave’ but Tolstoy draws our attention to a less heroic moment:

Ney, who came last, had been busying himself blowing up the walls of Smolensk which were in nobody's way, because despite the unfortunate plight of the French, or because of it, they wished to punish the floor against which they had hurt themselves.

Ney later persuaded Napoleon to abdicate and pledged his loyalty to the Bourbon restoration. But he returned to Napoleon’s side when Bonaparte came back to power in 1815. After Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo, Ney was tried for treason. At his execution he declined to wear a blindfold and gave the soldiers the order to fire. He reportedly said:

‘Soldiers, when I give the command to fire, fire straight at my heart. Wait for the order. It will be my last to you. I protest against my condemnation. I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her.’

Chapter 18: The Sublime Napoleon

This disastrous retreat is a challenge for historians who want to believe in the grand designs of great men. But since Napoleon’s actions were neither right nor just, historians devise a new concept of greatness, attributed only to heroes, and entirely removed from the question of what is good. So for fifty years, the whole world has worshipped the sublime Napoleon Bonaparte.

There is no greatness where simplicity, goodness, and truth are absent.

No shockers here: Tolstoy still doesn't think much of Napoleon. And all the historians have got it wrong.

But that notional idea of ‘greatness’ sounds pertinent to our age. Leaders who can get away with gross injustice due to their larger-than-life personalities. You can do anything as long as you make it look grand. The normal rules do not apply.

A chapter for our times.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

And that’s all for this week. I love to read your thoughts in the comments and the chat threads. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

I am looking at the book of War and Peace I have purchased for my re-read next year (this year was on kindle) and I can't believe we are so close to the end of this epic read. I would not have thought when we started I would want to read it again so soon but there you go! Have enjoyed it so much my family secret Santa this year is getting a gift subscription of Footnotes and Tangents and a copy of War and Peace. I am keen to know where the last stages of this book will take us, we seem so far from those days of carefree parties and trivial concerns. Enjoyed the links this week too, especially the story.

Yes, that last line of Chapter 18 hit hard this week.