Welcome to week 25 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 3, Part 1, Chapters 4 – 10.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. By upgrading to paid or making a one-off donation, you allow me to keep making these posts.

Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: The Emperor’s New Clothes

Reading creatively means bringing your own imagination to the story. There are the stories, ideas and experiences that influenced Tolstoy’s writing of War and Peace. But there are also your own points of reference that shape your reading and makes each encounter with War and Peace unique.

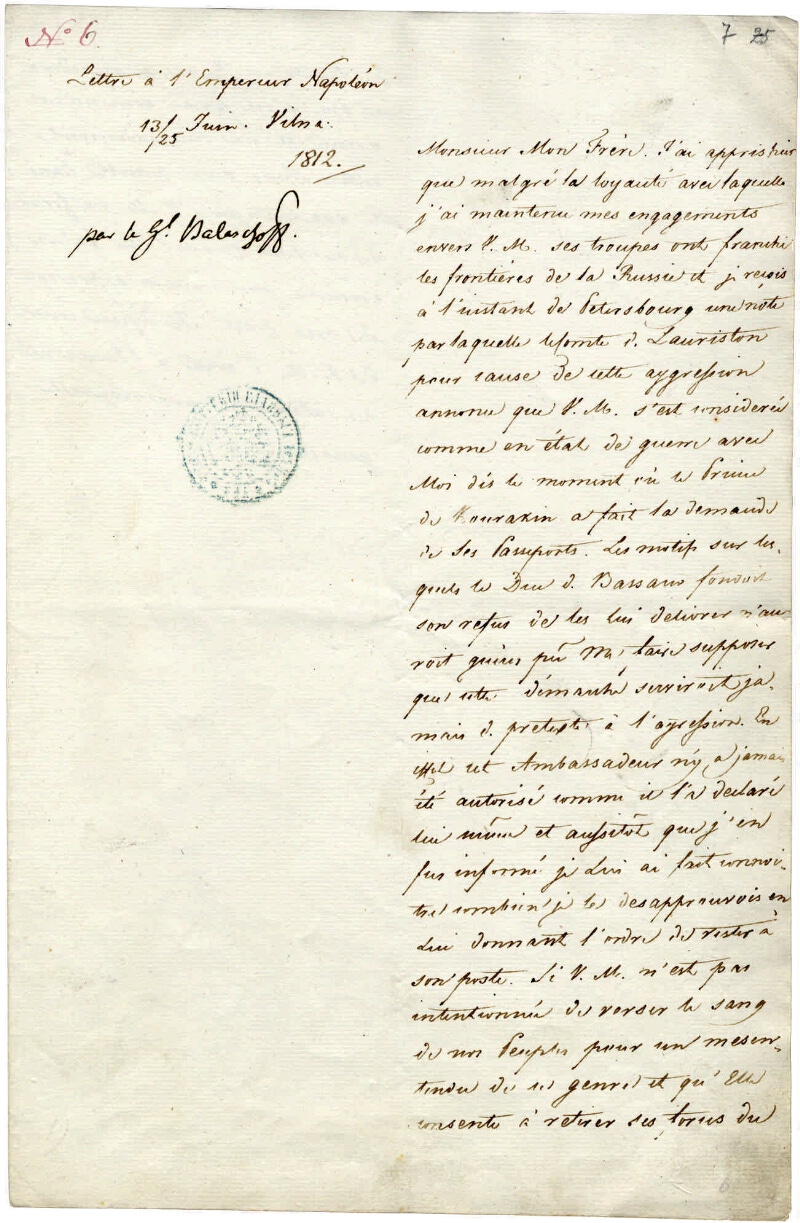

At two in the morning of the 14th of June the Emperor, having sent for Balashov and read him his letter to Napoleon, ordered him to take it and hand it personally to the French Emperor.

For me, the opening sentence of this week’s reading announces the start of a quest. We are Balashov and our goal is to find Napoleon and present him with Alexander’s ultimatum. Our mission appears simple but it is confounded by a strange shifting landscape, populated by unlikely and monstrous creatures.

On the road, we meet a wandering king who appears as confused as we are by his recent elevation to royalty. In a peasant’s hut, a gloomy ogre glares at us over a barrel. We are Alice through the looking glass and we are Little Red Ridinghood in the deep dark wood.

Our quest leads us in circles and back to where we started: Vilna, and the very house where Alexander gave us his letter for Napoleon. The world is askew and adrift and the borders of nations have shifted beneath our feet.

And when we finally meet the big bad boss, Napoleon himself, we discover an emptiness behind the Great Man. Now, we are Dorothy pulling back the curtain to reveal the Wizard of Oz – a pathetic and rather pitiful portrait of a tinpot dictator, shrieking and sniping but signifying nothing.

He’s been on everybody’s lips from the very first page of War and Peace. Pierre wanted to be him. Andrei wanted to best him. Nikolai wanted to kill him. He towers over us, though we only ever glimpse him from afar. Until now.

Because the big joke is that the so-called Saviour of Mankind is a thin-skinned egotist with little hands and a twitching leg. A rather ordinary man. Not a god or a devil, just a human at the head of one of the largest armies ever seen.

In the BBC dramatisation of War and Peace, Balashov is replaced by Boris Drubetskoy, getting his ear tugged in some French encampment. A sensible economisation of character and plot. But a mistake in my view.

Because the dramatic irony is that Balashov allows us to see something none of the fictional characters in War and Peace discover. Andrei got closest at Austerlitz, when that ‘small insignificant creature’ Napoleon stood above him on the battlefield.

If War and Peace is a quest for meaning, Napoleon is a deadend and a distraction. Whenever our characters think Napoleon is part of their quest, they are always horribly mistaken. Replace Bonaparte with any hero or villain, and the same rule applies: there is meaning in this world but it is not here.

‘Don't follow leaders. Watch the parkin' meters.’1

On Reading Book Three

Gustave Flaubert2 to Ivan Turgenev3, 21 January 18804

Thank you for making me read Tolstoy’s novel. It’s first rate. What a painter and what a psychologist! The first two are sublime; but the third goes terribly to pieces. He repeats himself and he philosophises! In fact the man, the author, the Russian are visible, whereas up until then one had seen only Nature and Humanity. It seems to me that in places he has some elements of Shakespeare. I uttered cries of admiration during my reading of it… and it’s long! Tell me about the author. Is it his first book? In any case he has his head well screwed on! It’s very good! Very good!

So far, do you agree with Flaubert?

Chapter 4: A Wandering King

General Balashov is sent to deliver Alexander’s letter to Napoleon. On the road he meets General Murat, who has remarkably become King of Naples. Kitted out like royalty, he rides into Poland like a fabled errant knight. He is chummy with Balashov, remembering the good times the French and Russians had in Italy. But the Russian general must get on, riding to Marshal Davout’s vanguard.

How do you feel about the return to war?

Why do you think Tolstoy includes these digressions away from his main fictional characters?

Murat, King of Naples

The man rode towards Balashov at a gallop, his plumes flowing and his gems and gold lace glittering in the bright June sunhine… Though it was quite incomprehensible why he should be King of Naples he was called so, and was himself convinced that he was so, and therefore assumed a more solemn and important air than formerly.

We met Murat earlier in War and Peace, as one of the three Gascons bluffing their way across the bridge out of Vienna. Who was Murat? For some, he was a brave and brilliant cavalry commander. But Tolstoy paints him as a flamboyant buffoon who has accidentally become King of Naples, and so puts on a ‘theatrically solemn countenance.’ His gallop down the roads of Poland, ‘without knowing why or where’, make me think a little of Don Quijote tilting at windmills. He’s the main character in his own medieval romance and he’s loving every minute of it.

Which is just as well, because his days are numbered. In 1815, he will be captured by the ‘real’ King of Naples, King Ferdinand IV, and executed by firing squad on 13 October. His last requests were a perfumed bath and an unobstructed view of his executioners. The twelve men were his own soldiers and as they took aim he said: ‘My friends, if you wish to spare me, aim at my heart.’

That’s the story anyway. The British vice-consul in Calabria reported it differently and you can read his first-hand account here.

Chapter 5: Walking in Circles

Balashov is interviewed by the Iron Marshal, Louis-Nicolas Davout, who treats him with contempt. Balashov moves with the French army’s baggage train to Vilna, now occupied by Napoleon. The emperor grants him an audience in the same house from which Alexander had dispatched him four days previously.

Does Davout remind you of anyone?

Do armies, and society more generally, need men like Davout?

We’ve all met Davout. I hope none of us have had the misfortune to be him. Tolstoy explains that such men exist wherever there is government, as naturally as wolves exist in nature: ‘The chief pleasure and necessity of such men, when they encounter anyone who shows animation, is to flaunt their own dreary, persistent activity.’

As I mentioned above, these two chapters read like a dark fairy tale. Balashov sets out in his best uniform, the Tsar’s letter under his arm, into the deep dark wood. He runs into a fairy king who doesn’t seem to know why he is here. And then, he is held captive by a cruel ogre with a love of barrels. He walks in circles and emerges from the enchanted forest feeling lost and dejected, to find the world remade with Napoleon at Vilna and his own emperor far, far away.

Napoleon’s bodyguard

Balashov finds Napoleon’s Mameluke, Rustan, outside the house at Vilna. Roustan Raza was born in Tbilisi in modern-day Georgia and was sold into slavery aged thirteen and taken to Cairo. The Sheikh of Cairo presented him to Napoleon in 1798 and he became Napoleon’s personal attendant and bodyguard. His desertion of Napoleon shortly before his abdication led to Bonaparte talking about Raza’s ‘betrayal’. Later in life, he wrote his memoirs of his time in Napoleon’s service which have since been translated into English.

Chapter 6: The Great Dictator

Balashov is amazed by the luxury and magnificence of Napoleon’s court. In the emperor’s presence, Balashov grows confused and is unable to deliver Alexander’s ultimatum. Instead, Bonaparte rants at the Russian envoy, justifying his actions and attacking Alexander. ‘What a splendid reign the Emperor Alexander might have had!’ He dismisses Balashov with his letter of reply to the Tsar.

Is this how you imagined Napoleon?

Describe Napoleon’s behaviour in three words.

Napoleon was in that state of irritation in which a man has to talk, talk, and talk, merely to convince himself that he is in the right.

This spectacular chapter gives us a long, hard look at the man who would want to rule the world. It is a portrait of a man-child. Should we be surprised? As Yiyun Li writes in Tolstoy Together:

Tolstoy forsees our miseries (and future generations’). Is there any solace in knowing that there is never a unique buffoon, a unique egotist, a unique sociopath, a unique dictator?

Chapter 7: The Hollow Man

To Balashov’s surprise, Napoleon invites him to dinner. The emperor is now in a contented and self-satisfied mood, surrounded by his courtiers and cronies. He asks many pointed questions about the road to Moscow and the city itself. Balashov bows his head and endures. Bonaparte pulls Balashov’s ear, a mark of favour, and sends him on his way. And so the war begins.

Why did Napoleon invite Balashov to dinner?

What would Tolstoy think of our own political leaders?

So here is the man Andrei admired and Pierre worshipped. Here’s the man who would be king of the world. In two chapters, Tolstoy shows the dictator’s two modes: the vainglorious windbag and the sniping bully.

If this is the Great Man, then we’ve gone behind the curtain and reached the hollow centre of our story. No one is going to gain any sort of enlightenment by fighting for or against Napoleon.

‘And the war began…’ So much terror and foreboding in four small words.

Balashov, who was on the alert all through the dinner, replied that just as ‘all roads lead to Rome, so all roads lead to Moscow’: there are many roads, and ‘among them the road through Poltawa, which Charles XII chose’.

Balashov ‘involuntarily flushed with pleasure’ here because he is referring to the triumphant defeat of a Swedish invasion of Russia in 1709.

Chapter 8: Buried Alive

After the events in Moscow, Andrei followed Anatole first to Petersburg and then to the army in Turkey. Andrei can no longer see the ‘lofty skies’ as his life has become ‘a low solid vault.’ He asks Kutuzov for a transfer to the Western front and the war with Napoleon. On his way, he stops at Bald Hills and argues with his father about Mademoiselle Bourienne. Despite Marya imploring him to forgive and forget, Andrei leaves his family on bad terms without remorse or regret.

Andrei • Kutuzov • Anatole • Marya • Prince Bolkonsky • Mademoiselle Bourienne • Nikolushka

Why can Andrei no longer see his lofty skies of Austerlitz?

‘Misfortunes come from God. Men are never to blame.’ What does Marya mean by this and is she right?

War and Peace is as much about how we lose sight of meaning as it is about finding it in the first place. This passage is a powerful addendum to Andrei’s lofty skies:

Not only could he no longer think the thoughts that had first come to him as he lay gazing at the sky on the field of Austerlitz and had later enlarged upon with Pierre, and which had filled his solitude at Bogucharovo and then in Switzerland and Rome, but he even dreaded to recall them and the bright and boundless horizons they had revealed. He was now concerned only with the nearest practical matters unrelated to his past interests, and he seized on these the more eagerly the more those past interests were closed to him. It was as if that lofty infinite canopy of heaven that had once towered above him had suddenly turned into a low solid vault that weighed him down, in which all was clear, but nothing eternal or mysterious.

It seems to me that Andrei is a man brought to life by others — Marya, Pierre, Natasha — but knows not how to produce and sustain that life within himself. Instead he goes to war: with his father, with Anatole, with himself. Forgiveness is a ‘woman’s virtue’, but peace is not found in war.

Marya, in contrast has found peace through religion, but at a terrible cost. And yet the most awful scene in this chapter is Andrei abandoning his son Nikolai. He repeats the mistake he made with his wife: running away from a messy human relationship for the simplicity of war and the oblivion of revenge.

Chapter 9: Too many cooks

Andrei catches up with the army and court at Drissa, where he is attached to Barclay de Tolly. Anatole is not there, so Andrei immerses himself in military matters. He identifies no fewer than nine factions with competing designs for the campaign. Most men are just in it for their own pleasure and advantage. But finally, wise heads win and convince Alexander to quit the army and appoint a commander-in-chief.

Andrei • Alexander • Barclay de Tolly • Pfuel • Arakcheev • Bennigsen • Tsarevich Constantine

Why does Tolstoy list at length the different factions at court?

How does Tolstoy contrast the leadership of Napoleon and Alexander?

Chapter 10: A Pfoolish Science

Andrei is summoned to court, where he meets Pfuel, the man masterminding the campaign. Like his father, Andrei takes a dim view of Germans and the science of war. Pfuel, we are told, is a man so in love with his theories that he is pleased by failure, all the better to prove the perfection of his abstract notions.

Are Andrei’s list of national stereotypes will relevant today?

What will Andrei say to Alexander? What part is he likely to play in the coming war?

Germans are the butt of plenty of jokes in War and Peace. Andrei appears to have inherited his father’s prejudices here. However, it is interesting how durable these national stereotypes are. Two centuries later, we can recognise Andrei’s archtypes of national character:

Pfuel was one of those hopelessly and immutably self-confident men, self-confident to the point of martydom as only Germans are, because only Germans are self-confident on the basis of an abstract notion—science, that is, the supposed knowledge of absolute truth. A Frenchman is self-assured because he regards himself personally both in mind and body as irresistibly attractive to men and women. An Englishman is self-assured as being a citizen of the best-organized state in the world and therefore, as an Englishman, always knows what he should do and knows that all he does as an Englishman is undoubtedly correct. An Italian is self-assured because he is excitable and easily forgets himself and other people. A Russian is self-assured just because he knows nothing and does not want to know anything, since he does not believe that anything can be known. The German’s self-assurance is worst of all, stronger and more repulsive than any other, because he imagines that he knows the truth—science—which he himself has invented but which is for him the absolute truth.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

Bob Dylan, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” on Bringing It All Back Home, 1965

Gustave Flaubert (1821 – 1880), French novelist and author of Madame Bovary and Sentimental Education. He died a few months after writing this letter.

Ivan Turgenev (1818 – 1883), Russian novelist and author of Fathers and Sons and A Month in the Country. He had a rocky friendship with Tolstoy, who once challenged him to a duel. On his deathbed he pleased with Tolstoy: “My friend, return to literature!”

Letter reproduced in Tolstoy Together by Yiyun Li.

Love this insight: “War and Peace is as much about how we lose sight of meaning as it is about finding it in the first place.” Thank you, Simon.

As an American, the idea of Napoleon takes on ominous meanings in 2024.