Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 14, 15, 16 & 17

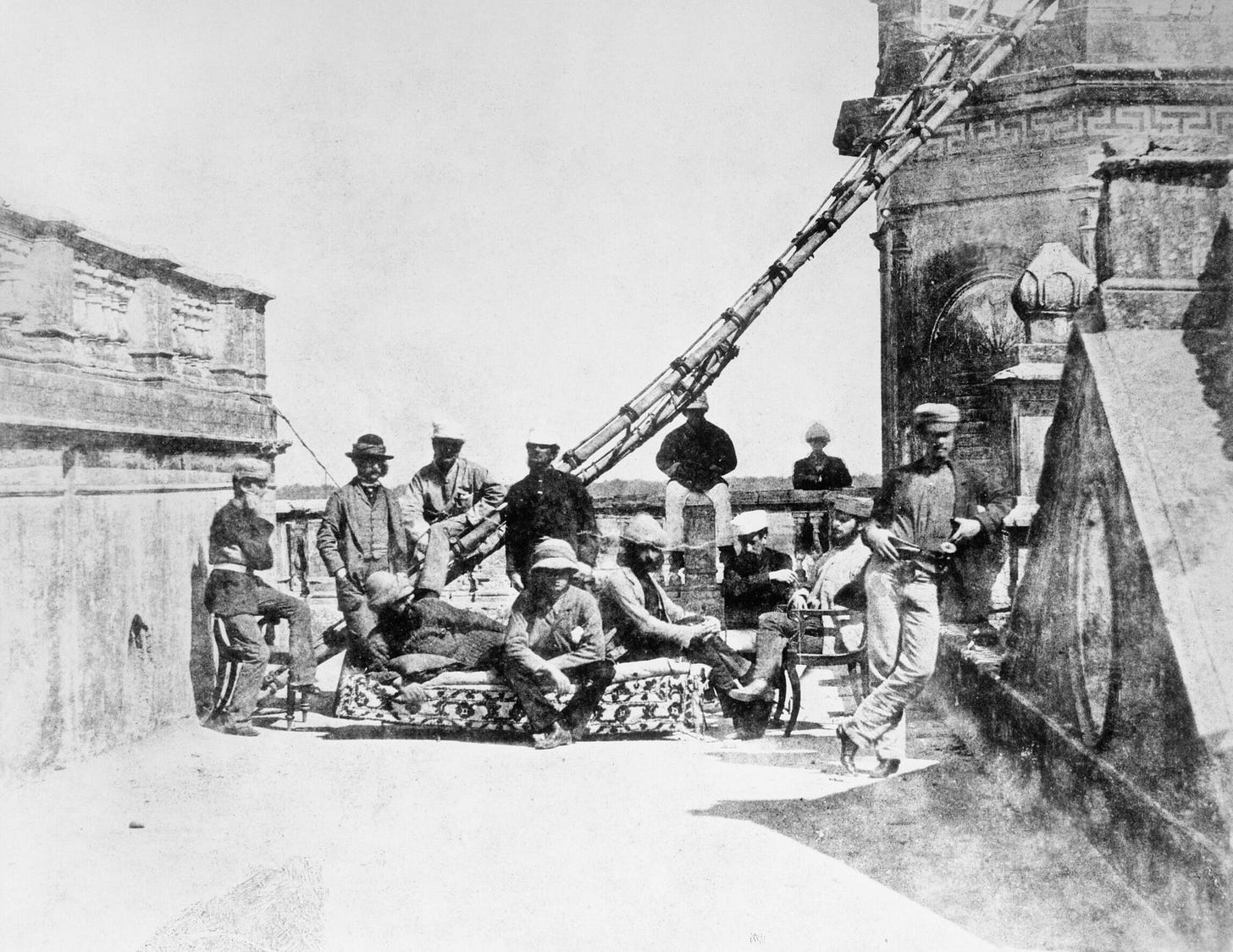

On the Collector’s tour of the enclave, he notes the Union Jack floating above the rising stench of rotting flesh. Lieutenant Cutter is busy digging defences against any attempt to blow them up from beneath. The Collector gives the go-ahead for an offensive gallery to mine the sepoys.

The Collector goes to war with Death, armed with statistics. He visits Hari, who has been moved to the tiger house from the relative safety of the Residency. Hari has taken up phrenology and inked the Prime Minister’s newly shaved head. Afterwards, the Collector joins the Padre in the dark, burying the dead.

He is not himself. He reaches out for comfort and holds Miriam, hunting scattered pearls. In his bedroom, he doesn’t duck when the musket balls fly, and his hand shakes the spoon that scatters the sugar. At night, his bed spins. Mrs Scott dies in labour, and Dr McNab dutifully reduces her death to ink; screams to silence as the gunfire continues outside.

On his birthday, Fleury joins Harry and Lieutenant Peterson on a sortie to coincide with Cutter’s explosions. Fleury arms himself with a Cavalry Eradicator with a certain design flaw. Peterson is killed, but Fleury returns a hero. Louise bakes him a cake and makes him a coat, all on Miriam’s instructions: ‘Happy Birthday Dobbin!’

In the dark, the Collector and the Padre dig more graves. They argue over which of the three dead is Catholic, and then Padre (spade in hand) resumes his spiritual resuscitation of George Fleury. The Collector considers how to defend what remains of the enclave with what remains of the garrison.

Footnotes

1. The Union Jack

The flag was crucial to the morale of the garrison; it reminded one that one was fighting for something more important than one’s own skin; that’s what it reminded the Collector of, anyway.

By custom, the British flag was raised at dawn and lowered at dusk. During the siege of Lucknow, it was nailed to the flag pole and flown day and night in defiance of the rebels, who tried to bring it down.

After the siege, the flag continued to be flown 24 hours a day, supposedly the only flag in the British Empire to be flown continuously. It was finally lowered in 1947 when India won independence.

2. The smell of empire

Combined with the animals scattered on the lawns, the smells from the hospital and from the privies, and from the human beings living in too close contact with insufficient water for frequent bathing, an olfactory background, silent but terrible, was unrolling itself behind the siege.

There’s something rotten in the siege of Krishnapur. The scent from the flower beds and the Collector’s verbena perfume has been replaced by the stench of butchered meat and the animal corpses on the lawn.

It often feels like the characters are trying to blot out the sights and sounds of the siege, but smell is a sense you can not easily escape. Louise notes that everyone has begun to smell, ‘it was so hard to keep yourself clean without the bearers to help.’

Hard to stay fresh without the structures of colonialism.

‘All smell is, if it be intense, immediate acute disease,’ claimed Edwin Chadwick, England’s first Public Health Commissioner, in 1846. Chadwick believed in the miasma theory of contagion from noxious bad air.

In the 1850s, John Snow challenged the belief that cholera was airborne, using statistical evidence to show that cholera outbreaks were clustered around infected water supplies.

A tangent…

But statistics and science will not speak to the whole of it, as the Collector discovers in these chapters. What we learn in books will be flatly refuted by our nostrils and the hairs on our arm: reactions learned in the womb and the crib and the yard; prejudices we’ll spend a lifetime dislodging, or else embracing; disgust and desire.

All of that stuff, all of our senses, senseless and out of control, when boxed in and besieged at the back of the bus, with people who aren’t like us, but are us, but we don’t know it. We can’t smell it yet. Because we’re too busy building up walls and scrubbing out scent of death and dirt and decay, and anything that might make us feel wrong or alive or feel anything at all.

We’re gravediggers, that’s all. Digging with cloth tied over our noses – our snouts – so we don’t smell ourselves stumble into the hole that we dug, into the blood and the gore that we spilt, and the stench that we made, while we thought we were building something beneficial, a beneficial disease no less, called Progress with a capital P.

Gravediggers, that’s all. For civilisation.

Footnote: The past stinks: a brief history of smells and social spaces. (The Conversation)

Tangent: My research on the politics of smell divided the internet – here’s what it’s actually about. (The Conversation)

3. Book knowledge

Surely what the Collector was doing as he pored over his military manuals, was proving the superiority of thhe European way of doing things, of European culture itself.

At various points this week, book knowledge is shown to be a poor substitute for a real understanding of the world.

The Collector’s books on siege defences cannot help Krishnapur’s diminishing number of able diggers. In the tiger house, Hari has picked up a book of phrenology and is inking this specious science onto the bald head of the Prime Minister.

Books give the Collector extraordinary powers:

An ordinary sort of man, he could, with the help of an oil-lamp, turn himself into a great military engineer, a bishop, an explorer or a General overnight, if the fancy took him.

Books contain statistics, ‘the leg-irons to be clapped on the thugs of ignorance and superstition which strangled Truth in lonely byways.’ Statistics arm the Collector against Death itself. He, the Collector, knows all there is to know about Death.

Except he doesn’t. His ‘death statistics’ cannot prepare him to be in the presence of ‘three silent figures sewen up in bedding’, ready for burial. The civilisation of books is no comfort.

And as he dug, he wept. He saw Hari’s animated face, and numberless dead men, and the hatred on the faces of the sepoys … and it suddenly seemed to him that he could see clearly the basis of all conflict and misery, something mysterious which grows in men at the same time as hair and teeth and brains and which reveals its presence by the utter and atrocious inflexibility of all human habits and beliefs, even including his own.

If the Collector is discovering the insufficiencies of book knowledge, Dr McNab is silencing a ‘chaotic universe’ with his pen. After Mrs Scott has died in childbirth, he writes up her last night with chilling medical distance.

In this room where throughout the night the most terrible shrieks of pain had echoed, there was now no sound to break the silence except the scatching of Dr McNab's pen-nib as he wrote and an occasional clink of china as he dipped it into the inkwell. Outside, the gunfire continued steadily.

There are many sieges within Krishnapur; many lines of battle. This is the war between the world as it is written and lives as they live and die.

Tangent: I’m not dead yet – The nineteenth-century obsession with premature burial. (The Paris Review)

4. Nocturnal Counsellors

Alas, the Collector knew that Machiavelli, another member of his staff of nocturnal counsellors, would not have wanted him to construct this second line of defence.

The phrase ‘nocturnal counsellors’ has a haunting quality about it that suggests the Collector is no longer the master of his books, but visited nightly by the phantoms of civilisation.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469 – 1527) is the Italian philosopher and author of The Prince, a treatise on statecraft. His advice is not consoling: defenders should not allow themselves the option of retreat. It seals their fate.

The Collector prefers the advice of Sébastien Le Prestre, Marquis of Vauban (1633 – 1707), regarded as one of the greatest military engineers of all time. Still, his saying, ‘Place assiégée, place prise!’ is cold comfort to Krishnapur. A besieged city is as good as taken.

Another French engineer, Louis de Cormontaigne, describes the ‘inevitable progress’ of a siege towards its necessary surrender. But the Collector knows that Krishnapur cannot surrender.

For a brief while, Fleury is animated by the ideas of another dead engineer, Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot. But Fleury lacks commitment to any one project and is soon distracted by his own fatally flawed invention: the Fleury Cavalry Eradicator.

Footnote: ‘All England Was Present at that Siege’: Imperial Defences and Island Stories in British Culture (History Workshop Journal, 2022)

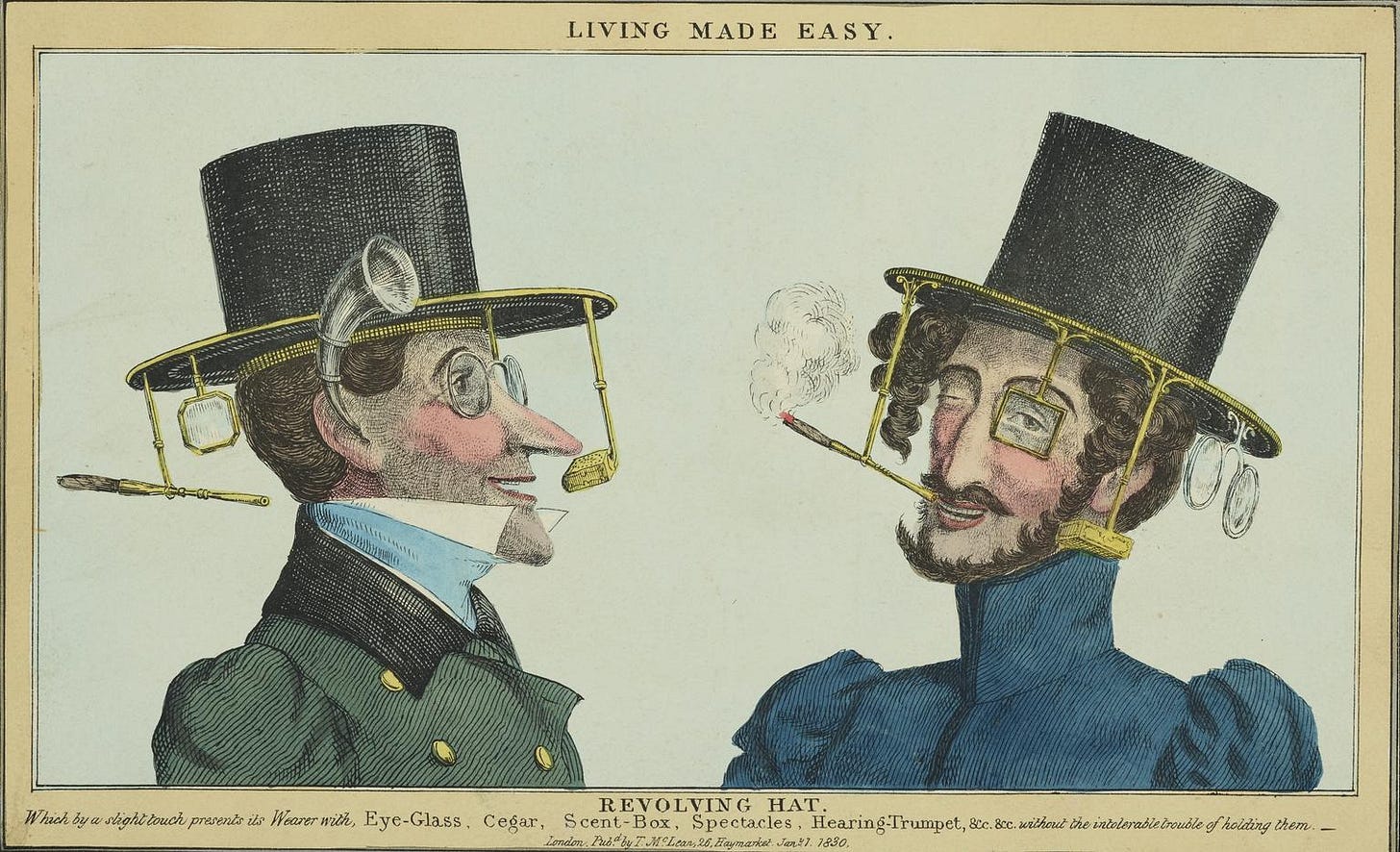

5. A tale of three heads and two hats

… on his way back, the Collector removed his pith helmet to air his scalp. It was his belief, based as yet on no scientific evidence, that lack of air to the scalp caused premature baldness.

The Collector wears a pith helmet: the iconic headgear of the British Empire. It provides sensible protection from the sun and has its origins in the cone-shaped salakot worn in the Philipines.

The Collector bares his head to stave off baldness. This Notes & Queries article provides quotations from the nineteenth-century medical profession in defence of the Collector’s risky theory:

The chimney-pot hat is very pernicious to health. It is hard, and therefore unyielding to the head. It is waterproof, and therefore keeps in the perspiration, and thus gives headache. The inside of the hat in summer-time is as hot as the hottest hothouse; and this excessive heat injures and tends to destroy the roots of the hair, causing the hair to fall off, and thus helps to produce baldness. How few men there are, who, after the age of 45, are not more or less bald! Women, who wear bonnets that are ventilated, retain their hair to extreme old age. I do not mean to say that hats are the only cause of baldness in men; but merely assert that hats, by inducing a high degree of temperature, and by promoting and keeping in a violent perspiration, are one reason of so much baldness in the sterner sex.

Shortly after removing his own hat, the Collector encounters a monkey that is unable to free itself of its sailor cap. The cap reads HMS John Company. John Company was a nickname for the East India Company; so is the monkey trying in vain to rid itself of the British?

Another animal symbolic of the subcontinent is the tiger. Hari has been moved to the empty tiger house to pace like a caged animal – ‘causing the Collector another severe inflammation of conscience.’

The Collector assumes that the Prime Minister has shaved his skull for ‘some religious significance.’ In reality, it is in the aid of science – albeit an erroneous branch of psychology. In fact, the Collector’s bare noggin and the Prime Minister’s ‘gleaming cranium’ are both bizarre experiments in science.

Tangent: The hidden racist history of hair loss (The Conversation)

6. Velocipedes

At the time it had been designed no satisfactory system of pedals had yet been devised and he himself was no longer supple enough to propel it by one foot on the ground, as its inventor had intended.

Tangent: Buster Keaton rides a ‘Dandy Horse’

Footnote: The bicycle’s bumpy history

7. History’s after-glow

'We look on past ages with condescension, as a mere preparation for us ... but what if we're only an after-glow of them?'

This quote appears on the back of my copy of The Siege of Krishnapur, and can be found online attributed to JG Farrell, usually favourably. It is always interesting to see how characters’ words get lifted out of context and become the presumed opinions of the author.

These are the words of the Padre, arguing with Fleury on the subject of religion, progress and civilisation. The priest is conservative and resistant to liberal, rationalist and reformist currents in Protestantism. To him, the world is getting worse as we deviate further from God’s word.

But this quote can be read differently. When we consider the past, we should not look on it as a staging post toward our present, but as a time in its own right. The dead were living once, with no knowledge of what the world would become. To return to the past, through fact or fiction, is to decentre ourselves from history: we are the after-glow; they are the fire.

Put this way, this quote may be viewed as a way of orientating ourselves in historical fiction, abandoning both condescension and romantic nostalgia for the past, in search of an understanding of the past as the living and burning heart of its very own moment.

Footnote: Can these bones live? (Hilary Mantel – Reith Lectures)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will read Chapters 18–23 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

"To return to the past, through fact or fiction, is to decentre ourselves from history: we are the after-glow; they are the fire."

Bravo Simon!

" in search of an understanding of the past as the living and burning heart of its very own moment."

This reminds me of something Mantel said about the trilogy too. That as she wrote it, none of the characters know that what will unfold will be 'history', dwelt upon for centuries and centuries and perhaps ever more. It was just what happened, they didn't know what was around the corner. No knowingness in the writing, the story or characters.

I find the quote from the Padre to Fleury to be very haunting. It can be read in so many ways. The more I think of it, the more it resonates. Is it a statement of humility, that however exceptional we may feel, we owe everything to the greatness of our past? Is it a pessimistic darkness, that we are doomed to failure and decline? is it a precursor to those who kick against the dying embers and re-light the fire of nationalism or empire which could itself be a warning? What a brilliant piece of writing.

The Collector (I am starting to like him very much, he's holding it all together) walking on the lawn, where they used to have their Garden Parties - such a very British thing- and it's become such a dangerous place, ruined, full of debris. On the other hand the Indians are now the ones, who are holding the parties, in their own way and style. The roles changed. And watching the Siege like some kind of entertainment show.