Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings.

Chapters 28–32

September comes and brings crowds of spectators to watch “the last act” of the siege of Krishnapur. They bring picnics, while behind the ramparts, “a few ragged, boil-covered skeletons” barter for lumps of sugar. Sparrow curry and a horse feast only go so far. Fleury bakes biscuits for Louise’s birthday. They are so hard they fear they’ll break their teeth.

The garrison prepares for a final attack from the sepoy besiegers. The women and children retreat to the banqueting hall, where the Collector anticipates they will make their last stand. He considers his useless collection and takes his pistols. The Magistrate declines an offer of a black beetle, which the Collector crunches like a chocolate truffle.

Fleury gets caught up in the final assault on the Residency. He is armoured with a cumbersome and ineffective fifteen-barrel pistol. In the music room, a violin saves his life, until his pistol relents and fires. The Collector manages a staged retreat and Harry fires his six-pounder at the sepoy magazine.

In the banqueting hall, the Padre makes his final assault on the atheism and apostasy of the Great Exhibition, berating a distracted and indifferent Collector. The Padre is attempting to throttle some religion back into his adversary, when the relief finally comes. “The heroes of Krishnapur” are not quite how General Sinclair expects, and Lieutenant Stapleton has second thoughts about rescuing Louise, his foul-smelling damsel in distress.

The Collector leaves Krishnapur and India, experiencing its vastness and the smallness of the siege. ‘“The Hero of Krishnapur’” retires from public life. He meets Fleury by chance many years later and they disagree on culture once more. Fleury has married Louise, Harry has married Lucy, and Miriam has married McNab.

‘Ah yes, McNab,’ said the Collector thoughtfully. ‘He was the best of us all. The only one who knew what was doing.’

Footnotes

1. Fed by ravens

Food has become an obsession with everyone; even the children talked and schemed about it constantly; even the Padre, at this period, could hardly fall asleep without dreaming that ravens were coming to feed him … but alas, no sooner did these winged waiters arrive with nourishment than he would wake up again.

This is a delirious allusion to the prophet Elijah, who was fed by ravens in the wilderness (1 Kings 17:4-6). There is some disagreement among scholars about whether this is a mistranslation – not least because ravens are ritually unclean. But beggars can hardly be choosers.

Ravens are corvids, an intelligent family of birds that includes crows, rooks, magpies, jackdaws, jays and choughs1. Magpies have a thieving reputation, known for their love of shiny things. Crows have been known to bring objects ‘as gifts’, as in the two examples linked below.

2. We happy few

The Magistrate’s shows a “loathsome display of cynicism” as the Collector prepares to rally the surviving few.

'I suppose he's going to tell us that gentlemen now abed in England will be sorry that they're not here,'

This is a reference to the St Crispin's Day speech delivered by Henry V in Shakespeare’s play on the eve of the Battle of Agincourt.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd—

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

The 1415 battle during the Hundred Years’ War was an unexpected English victory against a much larger French army. It became part of the mythology of “plucky England” defeating its adversaries with spirit and the longbow.

Shakespeare’s speech gave us the expression “band of brothers”, a phrase invoked by George Washington in 1783 at the end of the American War of Independence, and by Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile in 1793.

3. Going out with a bang

Vokins, in particular could not see how this announcement was supposed to set his mind at rest. His enthusiasm was in no way aroused by the prospect of being blown up honourably with the ladies and gents.

It is September, 1857. The hoped-for relief is currently engaged in retaking Delhi from the rebels. The capital had fallen in May. During the fighting, nine Europeans defended the Magazine, an immense store of munitions, against a rebel assault. Ultimately overwhelmed, the men chose to blow up the munitions and themselves in an enormous explosion.

In The Siege of Krishnapur, it is the sepoy magazine that is blown up:

The flash that followed seemed to come not just from the magazine itself but from the whole width of the horizon. The trees on every side of the magazine bent away from it and were stripped of their leaves. A moment later the men who watched it explode from the verandah felt their ragged clothes begin to flap and flutter in the blast. The noise that came with it was heard fifty miles away.

Before the world wars, ignited magazines were among the largest and most devastating explosions in history. In the eighteenth century, examples include the Siege of Almeida (1810) during the Peninsula War, and explosions at Fort Fisher and Mobile during and after the American Civil War.

In Delhi, three of the nine men survived. You can read about one of the survivors, William Raynor, in the link below:

4. The organ of hope

Before going down to the northern ramparts where the brunt of the attack was expected to fall, he took a last look round the room and saw Hari's phrenology book lying on the floor. He picked it up and opened it at random. It opened at 'Hope'.

Hopelessness is a theme explored earlier in the novel. And here at the end, the Collector blamed himself for the suicide of a young clerk from the Post Office. “I should have been able to give him something to hope for.”

5. Pepperbox pistols

Lastly he had picked an immense, fifteen-barrelled pistol out of the pile rejected by the Collector. This pistol was so heavy that he could not, of course, stick it in his belt; it was all he could do to lift it with both arms.

Trust Fleury to choose the most ridiculous and impractical weapon. The pepperbox was designed mostly for civilian use in self-defense and was popular with gold prospectors in the American Old West. It was impossible to aim beyond close range, which would be fine for Fleury in the Residency if it wasn’t for the fact that it wouldn’t fire.

The sepoy was a large and powerful man, Fleury had been weakened by the siege; the sepoy had led a hard life of physical combat, Fleury had led the life of a poet, cultivating his sensibilities rather than his muscles and grappling only with sonnets and suchlike ...

Initially, it is a violin and not the pepperbox that saves Fleury’s life. It is a satisfying call-back to Fleury “playing a violin to the owls that swooped across the starlit heavens”, as observed by a dismayed Dr Dunstaple at the start of the novel:

He was certain that it must have been George. Next morning he had come upon this violin, some leaves of music damp with dew on a music-stand, and a tall medieval candleabrum … all this was in a ‘ruined’ pagoda at the end of the rose-garden … Perhaps George was insane?

6. Death by symbolism

What do we make of the thick layers of symbolism in The Siege of Krishnapur? The Collector is nearly suffocated by the British flag. The articles of culture and civilisation become projectiles in a desperate defense of the Residency:

A sepoy with a green turban had had his spine shattered by The Spirit of Science; others had been struck by teaspoons, by fish-knives, by marbles; an unfortunate subadar had been plucked from this world by the silver sugar-tongs embedded in his brain. A heart-breaking wail now rose from those who had not been killed outright. 'How terrible!' said the Collector to Ford. 'I mean, I had no idea that anything like that would happen.'

Even the pillars of the banqueting hall turn out to be not made of marble. As the Collector will tell Fleury in the final chapter, “Culture is a sham.”

If the symbolism seems a bit thick, perhaps it is because the Victorians themselves were obsessed with symbolism. They are hoisted on their own petard. An appropriate expression that comes from Hamlet, and refers to a bomb-maker being blown up (“hoisted”) by his own bomb (“petard”).

A petard was usually deployed during a siege to break through fortifications.

Perhaps someone could turn that into an electro-metal miniature?

7. Gutta-percha

… there were inventions that might also serve God: the pews for the use of the deaf, for example, which could be connected to the pulpit with gutta-percha pipes.

The irony of the Padre and the Collector’s final clash over civilisation is that there is really nothing to argue about anymore: both men are disillusioned with the Great Exhibition and everything it represents.

Gutta-percha is a tree found in the Malaysian archipelago. It is used to make a thermoplastic latex, like rubber. However, it is less brittle than rubber and is not degraded by sea water. This made it ideal for electrical insulation in the nineteenth-century. It was used in the first transatlantic telegraph cables.

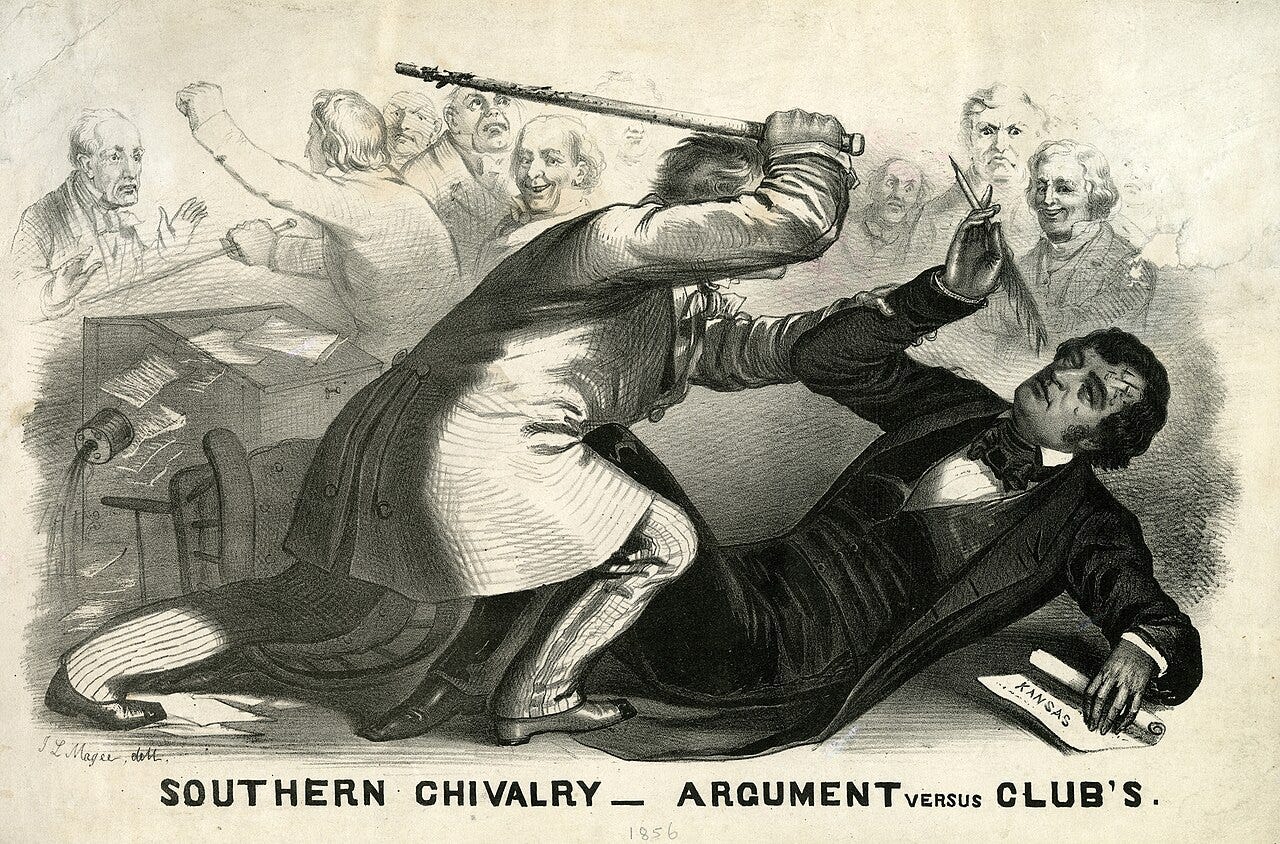

It was also used to make furniture and utensils, golf balls and football boots. In 1856, United States Representative Preston Brooks attacked Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate house with a cane made of gutta-percha. Civilisation in action.

8. Changing places

Feelings, the Collector now suspects, were just as important as ideas, though young Fleury no longer appeared to think so for he had given up talking of civilization as a ‘beneficial disease’; he had discovered the manly pleasures to be found in inventing things, in making things work, in getting results, in cause and effect. In short, he had identified himself at last with the spirit of the times.

In The Siege of Krishnapur, the two main male protagonists swap places in their position on progress and civilisation.

Early on, Fleury attempts to be more manly to get the girls. But “inventing things” has its own satisfaction, and he becomes the foppish green-clad hero of the siege. When he meets the Collector many years later, we are told he has “a number of children whom Fleury was inclined to hector with his views, showing extreme displeasure if they disagreed with him.” He had become a stifling Victorian patriarch in the mode of the Collector earlier in the novel. He had also acquired his own “collection of artistic objects of which he was very proud.”

Here is the archetype empire-builder, embodying the “spirit of the times.”

The Collector has taken the opposite journey:

'Culture is a sham.' he said simply. 'It's a cosmetic painted on life by rich people to conceal its ugliness.'

This seems closest to Farrell’s own position. Interviewed by the poet Derek Mahon in Vogue magazine, Farrell sums up his anti-materialism:

One devotes too much time to giving satisfaction to one's ego, time which could be better spent in fruitful speculation or in the service of one of the five senses. In any case, owning things which you don't need for some primary purpose, and that includes almost everything, has gone clean out of fashion... I'm sorry to have to break this news of the death of materialism so bluntly. I'm afraid it will come as a shock to some of your readers.

At his club, the Collector is “The Hero of Krishnapur”. General Sinclair considered these heroes “a pretty rum lot” who would be consigned to “an indistinct crowd of corpses and a few grateful faces” in a painting of “The Relief of Krishnapur.”

Well, I think Farrell makes the Collector the true hero of The Siege of Krishnapur, a man out of place in the spirit of an age addicted to empire.

Perhaps by the very end of his life, in 1880, he had come to believe that a people, a nation, does not create itself according to its own best ideas, but is shaped by other forces, of which it has little knowledge.

9. Divine instruments

So man is approaching a more complete fulfilment of that great and sacred mission which he has to perform in this world. His image being created in the image of God, he has to discover the laws by which the Almighty governs His creation; and, by making these laws his standard of action, to conquer nature to his use, himself a divine instrument.

The Editor of The Times is quoting from a speech made by Prince Albert in 1849.

10. Sequels

‘Ah yes, McNab,’ said the Collector thoughtfully. ‘He was the best of us all. The only one who knew what he was doing.’

McNab is the other character who emerges heroically from the pages of The Siege of Krishnapur. A rationalist, a practitioner of the scientific method, and a participant in the development of modern medicine – arguably the greatest human accomplishment of the nineteenth century.

In 1979, Farrell was working on something of a sequel to The Siege of Krishnapur. It would follow Dr McNab and his wife Miriam to the hill town of Simla, where they would meet a new cast of characters.

Farrell’s life and work were tragically cut short. In August, 1979, while fishing on the rocks at Bantry Bay in County Cork, he fell into the sea and drowned. Writing after Farrell’s death, Derek Mahon asked, “Who knows what magnificence he might have given us?” His last three novels were “only the beginning of something”.

The unfinished novel, The Hill Station, was published in 1981. If you would like to read it, I have included it on the Siege of Krishnapur shelf of the Footnotes and Tangents bookshop at Bookshop.org. I have just begun Troubles, the first of the three Empire Trilogy books, of which The Siege of Krishnapur is the second.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know your thoughts on completing The Siege of Krishnapur.

I will shortly add these posts to the book guide section of my website for future readers. Meanwhile, the slow reads for War and Peace and Wolf Hall continue. And in May, we will start the next slow read: A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

For our Wolf Crawlers: choughs appear on both Wolsey and Cromwell’s coats of arms, their beaks red-tipped as though dipped in blood.

Thank you for guiding us through TSOK. I would never have selected this book myself, but had total faith in your choice after being with you from the start of 2024. Great notes and insights as always. Have a fantastic break next month - so well deserved- and I look forward to your return in May. Happy holidays 😎 ✈️ 📕

Thank you for this wonderful slow read Simon I cannot tell you how much I have enjoyed it.

What a tragedy that Farrell died so young I am sure he would have produced so many more admirable novels.

That 18 barrell pepper box pistol may have been impractical to use but it looks bloody amazing.

As an aside, I came across, during some casual conversation, a Wiki entry about the 'Nabobs', which gives an insight into the disruptive nature of men who returned to England with riches from India:

++++

The English use of nabob was for a person who became rapidly wealthy in a foreign country, typically India, and returned home with considerable power and influence. In England, the name was applied to men who made fortunes working for the East India Company and, on their return home, used the wealth to purchase seats in Parliament.

A common fear was that these individuals – the nabobs, their agents, and those who took their bribes – would use their wealth and influence to corrupt Parliament. The collapse of the Company's finances in 1772 due to bad administration, both in India and Britain, aroused public indignation towards the Company's activities and the behaviour of the Company's employees. Samuel Foote gave a satirical look at those men who had enriched themselves through the East India Company in his 1772 play, The Nabob.

Nabobs became immensely popular figures within satirical culture in Britain, often depicted as lazy and materialistic, as well as a lack of temperance when regarding economic affairs in India. Nabobs typically came from middle-class backgrounds and tended to be of Caledonian origin, often being seen as low born social climbers.[13] Nabobs were often seen as challenging traditional values of middle-class British masculinity, as their weak moral grounds projected an effeminate symbol of a virtuous British culture. During the late 18th century, Britain was already struggling to define itself within its own imperial system—one that exposed cultural issues as well as growing the nation financially and socially. By taming the indulgent, uncultivated Nabob, and reintegrating both its character and wealth into sophisticated British society, the empire could reassert their vision of masculinity as well as push the image of an ethically upright middle class.[14] Beliefs that Nabobs, which typically worked as merchants and traders, had overstepped the unspoken socio-economic boundary through the surplus of riches in Asia quickly circulated. Nabobs quickly became weak-minded figures that had given in to the sensual temptation of colonial India that so many generations before them had been successful in resisting. Additionally, ideas of the Nabob’s unfettered opulence and aspiration to rise to governmental positions by unjustly purchasing Parliament seats were condensed into a satirical character.[