📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for War and Peace 2024.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 47 of War and Peace 2024

This week, we have read Book 4, Part 4, Chapters 7 – 13.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

Give someone War and Peace in 2025

This readalong will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so more readers can enjoy this slow read of War and Peace. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part next year. Paid subscribers can also join the slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy, read any of my book guides, or participate in the other 2025 slow reads.

This week’s theme: We Are Stardust

The stars, as if knowing that no one was looking at them, began to disport themselves in the dark sky: now flaring up, now vanishing, now trembling, they were busy whispering something gladsome and mysterious to one another.

What fools we have been. We who call ourselves human.

We wonder why we're born, why we suffer so and make others suffer more. Why we struggle and why we fight. Why we're always wanting more. Why we wonder, always wondering: What for? What for?

What fools we have been, wanting more.

We readers need heroes, and villains to despise. Judgement and redemption. A story that arcs to justice. A tale with a beginning and an end.

This is not that kind of story.

In 1812 and 2024, men will go to war. Forgetting who and what they are, they'll make up names for countries. With ideas that smell of gunpowder, they'll make monsters of their neighbours and fight devils in their sleep. And no one will dare whisper: What for? What for?

Every night, the same stars shine. That trembled over Moses and Mohammad, and that whispered to the first men, and women walking upright, hands holding tools, heads tilted to the sky.

The lofty sky. An infinite abyss, cradling us in our troubles as we wander down below.

Each of us, so different, so legitimately peculiar; messed up and all so broken, in our own peculiar way.

I am you and I’m not you. 13.7 billion years, of stardust and starlight colliding to make children of the dust. Dust that dared to think, and ask the silly question: What for? What for?

Pierre Bezukhov, you holy fool. You seeker. Short-sighted in your spectacles, scrutinising sacred texts for meaning that isn't there. You fool, Pierre. The answers were always straight in front of you. They were always at your feet.

We are stardust, we are human. We are wonderfully complete. The stage-coach driver, the post-house overseer, the peasants on the road. Everyone you meet, in this book and in life.

Be still and listen gently now, to each and every one. There is an answer to the question. What for? What for?

Chapter 7: Walking Walls

On the last day of the battle of Kransoi, an infantry regiment stops at a village for the night. With a cold, frosty night ahead of them, the men prepare the camp. They merrily and noisily move a wattle wall down through the village. An officer complains of the noise and strikes one of the men. Inside the officers’ hut they plan tomorrow’s manoeuvres, while outside men settle around fires and steam the lice from their shirts.

‘Now, all together! But wait a moment, boys ... With a song!’

From the field marshal to the field and the forest and the stary night. We telescope in from those unimaginable numbers to fifteen jolly soldiers moving a wattle fence for shelter.

There is something archaic, and primeval about this scene. Wattle has been with us for over 6,000 years. The Roman architect Vitruvius wrote of it: a woven lattice of supple branches. I can feel the frozen air seeping through its gaps. Snow is falling. The frost is keen. Winter is here.

This chapter is all about the contrast between the officers and the common soldiers. The officers shelter from the cold night, drinking tea in their hut and discussing battle plans that will come to nothing. Outside, the ‘huge, many-limbed animal’ of the regiment faces the elements with a brave face and a merry song. Despite their desperate situation, the men seem strong, organised and in high spirits.

Given this, why do they allow their superiors to treat them so poorly? Why don’t they revolt?

Is their merry mood convincing? When have you experienced such camaraderie and merriment in challenging circumstances?

Further resources:

Chapter 8: Zombies and Vampires

The soldiers of the Eighth Company sit around a fire, telling stories. They argue and joke and gaze at the stars. They remember the battle of Borodino, the ‘only one worth remembering’, where it took 20 days to cart away the dead. They speak of bodies that won’t rot and a French emperor who can transform himself into a bird.

‘They say Platov took 'Poleon himself twice. But he didn't know the right charm. He catches him and he catches him again—no good! In his hands there's nothing but a bird who spreads his wings and flies away. And you can't kill him either.’

Platov commanded the Don Cossacks as they chased the remnants of the Grande Armée out of Russia. He later visited London, where he was awarded a golden sword and an honorary degree from the University of Oxford.

The dancer, the Jackdaw, the sergeant-major. What a skilful sketch of walk-on characters, telling tales in the frozen night. And what stories! Zombie Frenchmen whose bodies stay fresh on the ground, and an emperor who flies like a bird.

‘Well, anyhow we’re going to end it. He won’t come back here again.’

Further resources:

Chapter 9: Song and Stars

The Fifth Company are camped by a wood. Around midnight, Ramballe and his orderly Morel stagger from between the trees. Ramballe is taken to the officers’ hut while a drunk Morel stays with the soldiers to sing songs, eat and watch the stars twinkle in the heavens.

Ramballe returns! We last saw him drinking in the dawn with Pierre on the eve of the fire of Moscow. A romantic who is quick to love and forgive, he is one of the 26,500 French prisoners taken at the Battle of Krasnoi.

One soldier mocks the unfortunate captain, but the others rebuke the jester and help Ramballe to the officers’ hut. It is a consoling scene. In the previous chapter, the French were demons, who gobbled up gentry grub and lay ‘white as paper’ on the battlefield. Now, Morel eats peasant porridge and sings with them.

'They are men, too,' said one of them as he wrapped himself up in his coat. 'Even wormwood grows on its own root.'

What do you think this means?

I can’t find an explanation for this folk saying, but I think it means that however strange we find other people, we can come to together to share food, songs and smiles across a campfire. And look up:

They all grew silent. The stars, as if knowing that no one was looking at them, began to disport themselves in the dark sky: now flaring up, now vanishing, now trembling, they were busy whispering something gladsome and mysterious to one another.

There it is again. War and Peace’s main protagonist. The eternal, infinite and lofty sky.

Long live Henri IV!

This is the song Morel sings to the Russian soldiers:

The tune celebrates the first Bourbon king and was sung by royalists in opposition to the French Revolution. It became the de-facto national anthem after Napoleon’s fall and the restoration of the monarchy. In his 1830 short story ‘The Blizzard’, Alexander Pushkin mentions it as a song sung in Russia after Napoleon’s defeat.

Chapter 10: The End of the Road

The French cross the Berezina and leave Russian territory. Kutuzov halts the army at Vilna. The emperor joins the army and expresses displeasure with Kutuzov’s conduct of the campaign. He explains his plan to take the war abroad, leaving it to Count Tolstoy to award Kutuzov with a medal and show him the door.

He saw on the one hand that the military business in which he had played his part was ended and felt his mission was accomplished. And at the same time he began to be conscious of the physical weariness of his aged body and of the necessity of physical rest.

In Vilna, Kutuzov kicks back and gets drunk. The French have left Russia and he is not the field marshal to chase them to Paris. The Tsar's brother tells him they are displeased. But I don't think the old man cares anymore. He knows what he's achieved. He'll take his medal and head in search of peace and rest.

The Grand Duke Constantine is Alexander’s younger brother and heir-apparent. We haven’t seen much of him since the disastrous Austrian campaign at the beginning of the novel. Well, here he is, arriving at the end of our story to tell Kutuzov of ‘the emperor’s displeasure.’

After the war, Constantine became Governor of Poland and settled there, secretly renouncing his claim to the Imperial throne. In 1825, his refusal to succeed his brother as Tsar led to the Decembrist revolt. Tolstoy’s original intention was to tell the story of a participant in this uprising, who is exiled to Siberia and later returns. All that remains of that character is his name: Pyotr. Pierre.

Further resources:

Chapter 11: And So He Died

The next day, Kutuzov holds a dinner where he presents the emperor with the captured standards of the French. Alexander calls his field marshal a comedian and Kutuzov advises against continuing the war beyond Russia. The emperor takes control of the army and with nothing left to give, Kutuzov dies.

Kutuzov did not understand what Europe, the balance of power, or Napoleon, meant.

Of the hundreds of historical figures in War and Peace, Kutuzov is given the biggest part. He's as essential to the narrative as Andrei, Pierre or Natasha.

Unlike them, he doesn't change. His main characteristic is constancy. He embodied the spirit of the book: patience, an inner peace and a hatred of war. He doesn't understand Napoleon, and if Alexander wants to be Napoleon, he'll need a general who believes war is worth dying for.

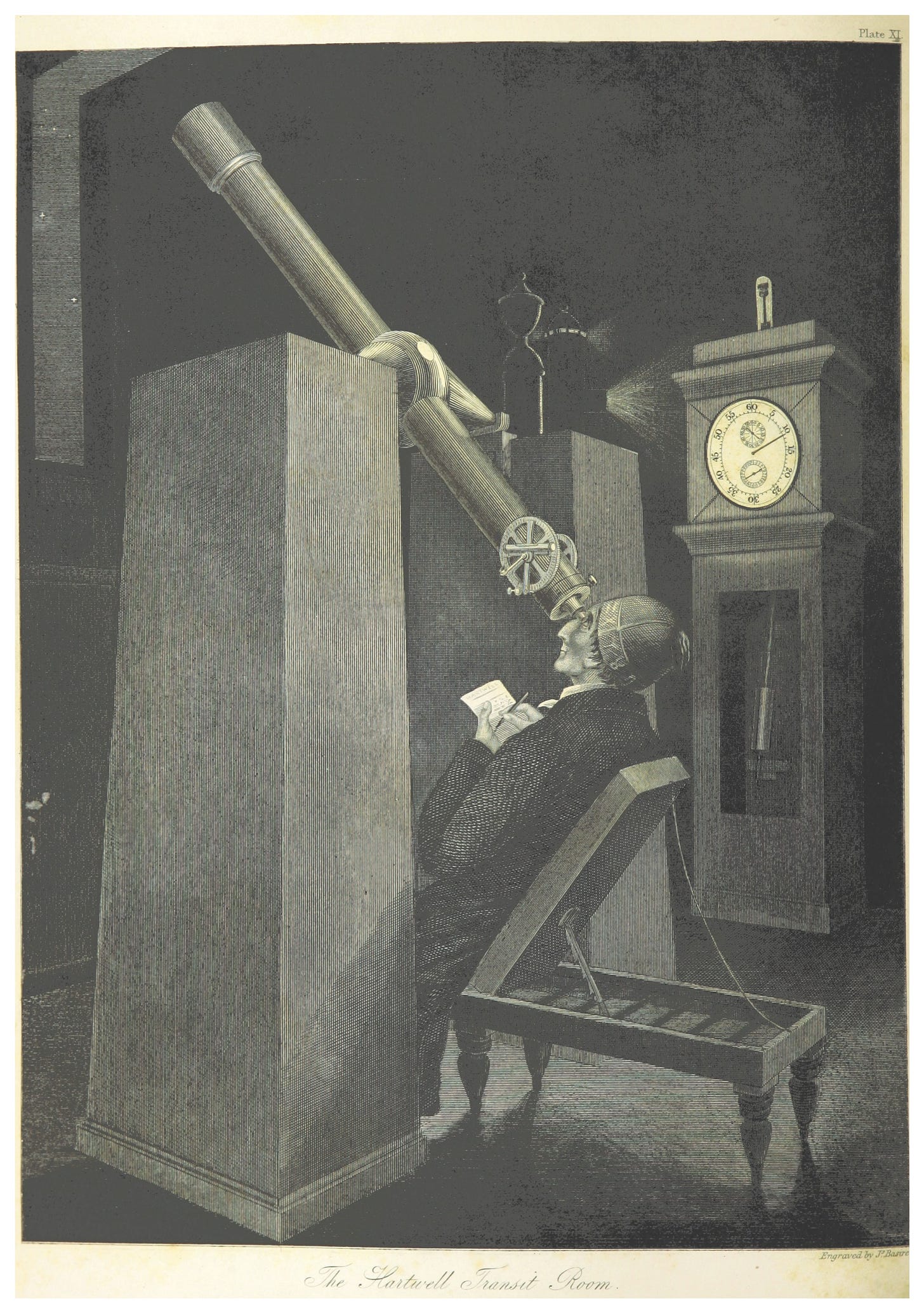

Chapter 12: Pierre’s Telescope

The day of his rescue, Pierre learns of the deaths of Petya, Andrei and his wife Hélène. He falls ill and takes three months to recover. During his recovery, he re-discovers his external freedom and abandons his search for the meaning of life. He puts aside his telescope, and regards the world around him.

Now, however, he had learnt to see the great, eternal, and infinite in everything, and therefore—to see it and enjoy its contemplation—he naturally threw away the telescope through which he had till now gazed over men’s heads, and gladly regarded the ever-changing, eternally great, unfathomable and infinite life around him. And the closer he looked the more tranquil and happy he became.

It may seem strange that Pierre is so happy. He has learned of the deaths of his wife, his friend and his namesake, Petya. We, poor readers, have endured each of these deaths and are feeling fairly miserable about all of it. So it is easy to reproach Pierre here and feel upset, as though he won’t partake in our grief.

But Pierre has been on this long journey of fire and ice, the firing squad and the Smolensk road. On that journey, he lost everything but the one thing that could not be taken away from him. Remember that night outside Moscow:

Pierre glanced up at the sky and the twinkling stars in its far-away depths. ‘And all that is me, all that is within me, and it is all I!’ thought Pierre. ‘And they caught all that and put it into a shed boarded up with planks!’

They couldn’t capture his ‘immortal soul’ or, as he later reasons, the source of our ‘full strength of life’: our capacity to choose what we give our attention to and how we respond to it. This realisation frees him to re-focus on and become curious about the people around him.

Chapter 13: Legitimate Peculiarities

Pierre remains as absent-minded and kind-hearted as before. But he is happier, less anxious and a better listener. His cousin Katiche comes to like him. The freemason Willarksi sees a man mired in apathy and egotism. Pierre’s finances are as chaotic as ever and in January he resolves to go to Moscow, settle his wife’s debts and rebuild the Bezukhov townhouse.

Count Willarski sponsored Pierre’s admission to the Brotherhood of Freemasons in 1807. He reappears here to remind us of what Pierre might have become: a bored official who regards his family life as a hindrance to his masonic interests. Willarski is still looking past and through people in search of mysterious truths. But despite himself, he enjoys Pierre’s company. They now have very little in common, but Pierre’s curiosity and lack of judgment make him a pleasant companion:

There was a new feature in Pierre's relations with Willarski, with the princess, with the doctor, and with all the people he now met, which gained for him the general goodwill. This was his acknowledgement of the impossibility of changing a man's convictions by words, and his recognition of the possibility of everyone thinking, feeling, and seeing things each from his own point of view. This legitimate peculairty of each individual, which used to excite and irritate Pierre, now became a basis of the sympathy he felt for, and the interest he took in, other people. The difference, and sometimes complete contradiction, between men's opinions and their lives, and between one man and another, pleased him and evoked from him an amused and gentle smile.

This lengthy quote encapsulates for me a core theme of War and Peace. Like Pierre, we were initially excited or irritated by each character – including Pierre. We rushed to judgment, demanded they change, insisted they redeem themselves to earn our respect.

We were well wide of the mark. That approach served no one. It dulled our senses and dimmed our wits. But like Pierre, we discovered a new way of seeing, interested in the ‘legitimate peculiarity of each individual’, finding pleasure in and feeling sympathy for the contradictions between people’s words and actions, from this moment to the next.

Bezukhov means ‘the earless’ one. From the moment he walked into Anna Pavolvna’s salon he was interested in life but not listening to it. He sought answers but he couldn’t hear what was being said. Pierre’s quest in War and Peace is our journey in reading it. A strange unfinished voyage in the art of noticing; a slow and mindful listening to the universe, to others and to ourselves.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

If you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. This readalong runs next year and you can give someone a gift subscription so they can also savour this slow read. If you refer friends to Footnotes and Tangents you can get some extra months free, check out the leaderboard for more details.

That’s all for this week. I love reading your thoughts in the comments and the chat threads. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

Oh, Simon. Today’s posts are incredibly moving. I clicked the link to Joni singing “Woodstock” and let it play in the background as I read the update. The orchestration, her voice and lyrics are the perfect soundtrack for today’s revealed, timeless truths. Thank you for so beautifully weaving it together. I confess a few grateful, heartfelt tears this morning.

The sky, my old friend, I’ve learned to see as a main character in my own life. I love its return to the pages here.

Thank you for guiding us on this journey!