‘So now get up.’

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned towards the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

Welcome to Wolf Crawl. I am your guide,

, and this is a year-long slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy: Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies, and The Mirror & the Light.Each week, I dive into the detail, with summaries, background, footnotes and tangents to enrich your reading. I am joined on this journey by

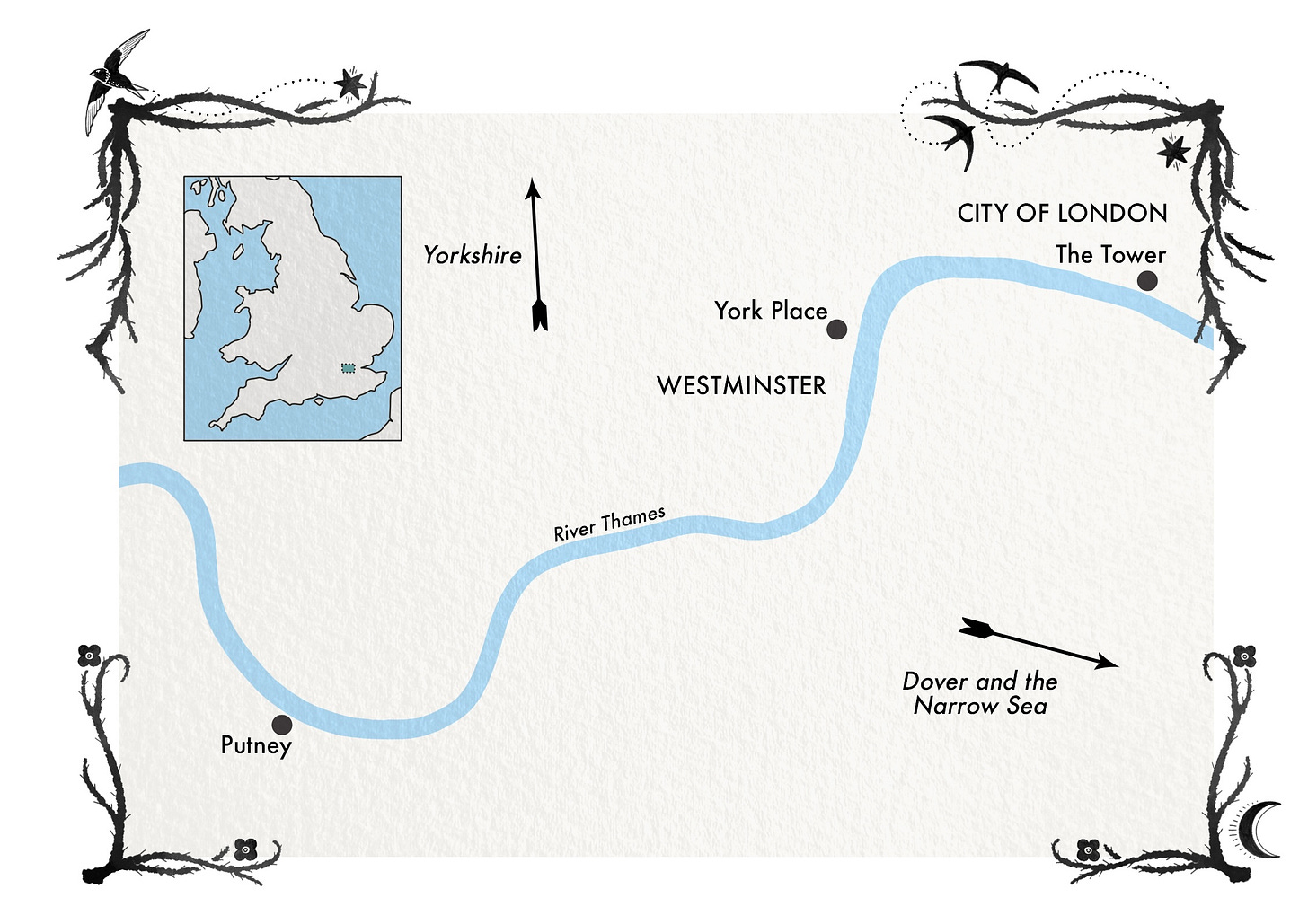

, who delves into the archive on our behalf, and Matt Brown, who makes maps to help us find our way through Cromwell’s world.You can find the reading schedule and plot summaries for the full cast of characters on my website, Footnotes and Tangents. There, you can join other slow reads, including Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, The Siege of Krishnapur by J. G. Farrell, and Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story illustrated by a map created by Matt Brown. This is followed by a few footnotes of interest. This week, I take a closer look at those opening lines, introduce the themes of paternity and stitchwork, discuss the tricky narrative voice of ‘He, Cromwell’, and meet His Grace, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. We then head to the archives with Bea Stitches, take a look at all things ghostly in The Haunting of Wolf Hall, and close with my favourite quote of the week.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you’ve been and what you’ve found.

To get these posts in your inbox or the Substack app, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for ‘2025 Wolf Crawl’ in your subscription settings.

This week’s story

This week, we are reading Part One, Chapter I. Across the Narrow Sea, Putney, 1500, and Chapter II. Paternity, 1527. This section runs from pages 1 to 33 in the UK Fourth Estate edition and from pages 3 to 30 in the US Picador edition. It begins, ‘So now get up’, and it ends, ‘A black-faced imp with a trident is pricking his calloused heels.’

We meet Thomas Cromwell as a 15-year-old boy in Putney in 1500. His father, Walter, has beaten him almost to death. He resolves to leave home and become a soldier overseas. His sister Kat and her husband Morgan Williams give him money for the journey. He goes to the port of Dover, where he makes money with the ‘three card trick’ and befriends three brothers from the Low Countries, across the Narrow Sea1.

We fast-forward to the year 1527. We are at York Place2, the London residence of the Archbishop of York, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Cromwell is now over forty and Wolsey’s ‘man of business’. He has just returned from Yorkshire, where he and Wolsey are much despised for the cardinal’s plan to close some thirty monastic institutions. But Wolsey’s mind is preoccupied by the king’s ‘great matter’: the divorce of Henry’s first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon.

Footnotes

1. From Putney cobbles to Tower Hill

It knocks the last breath out of him; he thinks it may be his last.3

I will mostly avoid spoilers in these posts. But there is one detail we cannot escape: On 28 July 1540, an executioner at Tower Hill will remove Cromwell’s head and end his life. We read these books knowing that Cromwell will one day be the second most powerful man in England, beheaded at the behest of the king.

So, our ending is in our beginning. We are ‘felled, dazed, silent’. A lowly blacksmith’s boy on the floor, as low as we can go. Head turned to the gate, like a condemned man hoping for a last-minute reprieve and pardon. ‘One blow’ separates us from the land of the dead.

The opening scene puts us in Cromwell’s body. Historical fiction can paint a picture from history, but what Mantel does is thrust us into the past in the present tense, unfolding in a moment of bodily pain. She imaginatively reanimates a real body from the past and asks, what did it feel like to inhabit that sixteenth-century skin?

We begin with a command from a father to his son. Walter propels into motion a vertigo-inducing story of ascent. Look out for ladders – and stairs – in the pages ahead, because everything that follows is as if a reply to Walter: ‘So now get up.’

2. Stitching the story

…if he squints sideways, with his right eye he can see that the stitching of his father’s boot is unravelling.4

The story of Wolf Hall is written on bodies. It is also threaded into the weave. Walter’s boot is the first stitch of our story. Throughout these books, Cromwell’s eye will be drawn to many threads, embroidery and lacework, the measure of cloth and the depth of a tapestry.

Pay attention to the stitchwork: it tells a tale. In Chapter II, Paternity, Cromwell looks into Wolsey’s tapestry and sees his own past. Queen Sheba reminds him of Anselma, a woman he knew in Antwerp. The cloth industry was immensely important to the sixteenth-century world. The fabrics you wear and display tell everyone who you are. It is a Tudor language, which we must learn as we read Wolf Hall.

We are immensely fortunate to have with us a resident expert on stitchwork in the Cromwell trilogy: Dr Lucie Bea Dutton.

has spent many years reimaging the Cromwell books on cloth, and in June 2024, I had the enormous pleasure of seeing her project at the at Cadhay House in Devon. I will share some of her work in these posts.David Holland organised the Wolf Hall Weekend. Here, he interviews

about her work and the theme of stitching in the Cromwell trilogy:3. He, Cromwell

New readers to Wolf Hall are struck by an unusual narrative style. Initially, it can be a challenge. But once you get the hang of it, you’ll see how fundamental it is to the magic of the writing.

Unless otherwise specified, ‘he’ refers to Cromwell. The story is told from his point of view, and we know nothing that he does not see. As readers, we sit perilously close to his eye-line. We are him, and yet we are not him.

If Wolf Hall was written in the third person, Cromwell would be just another Thomas in our story. If Mantel had made Cromwell narrate his tale in the first person, it would have been contrived: Cromwell wrote no memoirs, and most of the manuscripts written in his own hand were destroyed on the day of his arrest.

This narrative voice flits between first, second, and third person: we see him, we are him, and we watch how others regard him.

Take, for example, this paragraph:

Stephen sings always on one note. Your reprobate father. Your low birth. Stephen is supposedly some sort of semi-royal by-blow: brought up for payment, discreetly, as their own, by discreet people in a small town. They are wool-trade people, whom Master Stephen resents and wishes to forget; and since he himself knows everybody in the wool trade, he knows too much about his past for Stephen’s comfort. The poor orphan boy!5

This is about Cromwell’s nemesis, Stephen Gardiner. But ‘your low birth’ is directed at Cromwell. ‘He himself’ is Cromwell. And ‘the poor orphan boy!’ is his own sly thought directed back at Stephen.

If you have trouble getting used to this style, I recommend the audiobooks. The trilogy is magnificently read by actor Ben Miles, who also performed as Cromwell in the Royal Shakespeare Company adaptations of the books.

Hearing the language can really help. Either way, once you are accustomed to this narrative voice, you’ll have little problem working out who ‘he’ is, from one sentence to the next.

4. Paternity: Fathers and sons

This is a story about fathers and sons, literal and figurative. Having fled Walter Cromwell, Thomas is a son without a father. The King of England is a father without a son. As Cromwell’s patron, Wolsey becomes a father figure to a talented and resourceful lawyer rising up in the world. Cromwell has his own son, Gregory, but he also takes many young men under his wing. This week, we met the first: Rafe Sadler.

Another theme that runs through these books is how women fight for space in this patriarchal society that grants them few rights and little protection. Henry VIII has ‘a daughter living’ but no male heir. Had Mary been considered the equal of a prince, there would have been no need for a divorce, and no need for Thomas Cromwell.

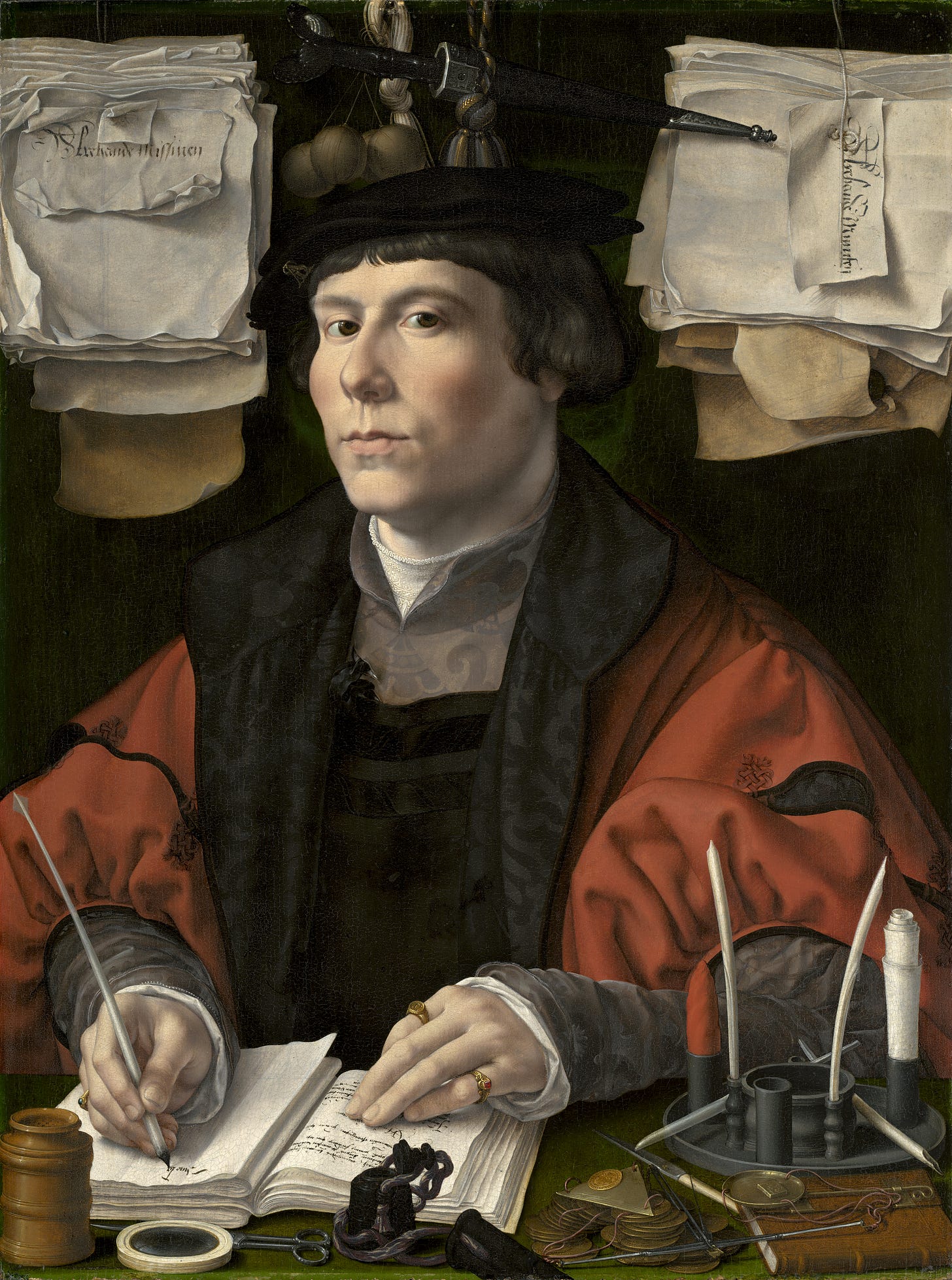

5. His Grace, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

‘… but the king, alone, has no son. Whose fault is that?’ 'God's?' 'Nearer than God?' 'The queen?' 'More responsible for everything than the queen?' He can't help a broad smile. 'Yourself, Your Grace.' 'Myself, My Grace.'

In these books, almost every character is based on a real historical person. There’s an astonishing amount of archival research behind Mantel’s creations. But remember that perspective and point of view are everything. What we see in Wolf Hall is Mantel’s version of Thomas Cromwell’s view of the people he knew.

Later, when we meet the king, Thomas More or Anne Boleyn – we see them through Cromwell’s eyes. Mantel is purposefully painting a partial picture of the Tudor court. And in Cromwell's life, one man looms larger than all others.

‘I needed to know Wolsey to understand Cromwell’, wrote Mantel.6 We know Thomas Wolsey as the ‘butcher’s boy’ who dared to eclipse the King of England in his ostentatious displays of wealth and power.

By 1515, this lowborn prodigy of Magdalen College, Oxford, was a cardinal, archbishop and Lord High Chancellor of England. His lavish residences at Hampton Court and York Place rivalled those of the king. He had become, in the eyes of his enemies, alter rex, ‘the other king.’

This is how we see Wolsey, Mantel says, as the ‘great scarlet beast’ of an ‘old world’. But Wolsey earned the loyalty and love of Thomas Cromwell. Next week, we will meet another of the cardinal’s servants, George Cavendish. He was Wolsey’s first biographer. His book, Thomas Wolsey, Late Cardinall, his Lyffe and Deathe, illuminates the man Cromwell must have seen: mild-mannered, cultured, funny, ambitious and fiercely competent.

Wolsey is Cromwell’s patron, mentor and surrogate father. Where Walter is an ignorant and violent thug, Wolsey is a gentle uncle with wise words. But he lacks patience for detail:

When he once, as a test, explained to the cardinal just a minor point of the land law concerning – well, never mind, it was a minor point – he saw the cardinal break into a sweat and say, Thomas, what can I give you, to persuade you never to mention this to me again? Find a way, just do it, he would say when obstacles were raised; and when he heard of some small person obstructing his grand design, he would say, Thomas, give them some money to make them go away.7

Cromwell reveres Wolsey, but he will outshine his master in this regard. His patience is frightening. His grasp of detail, alarming.

Wolsey has put him in charge of what the historian Diarmaid MacCulloch calls Wolsey’s ‘legacy project’: finding money for his two colleges and princely mausoleum. Cromwell turns out to be very good at finding money, getting things done, and making people go away.

In the Archives with Bea Stitches

Finding records for the first two chapters of Wolf Hall has proved to be a bit of a challenge. We know so little about Cromwell’s childhood and youth – although it is possible to find records of a few magistrate hearings involving Walter. For much of the 1520s, Cromwell worked as a lawyer, and spent time drawing up leases, wardships, and standard legal drafting – some of these documents survive, but they don’t give us much of an insight into the man himself.

But once we get to about 1527, he, Cromwell, starts to emerge from the archives.

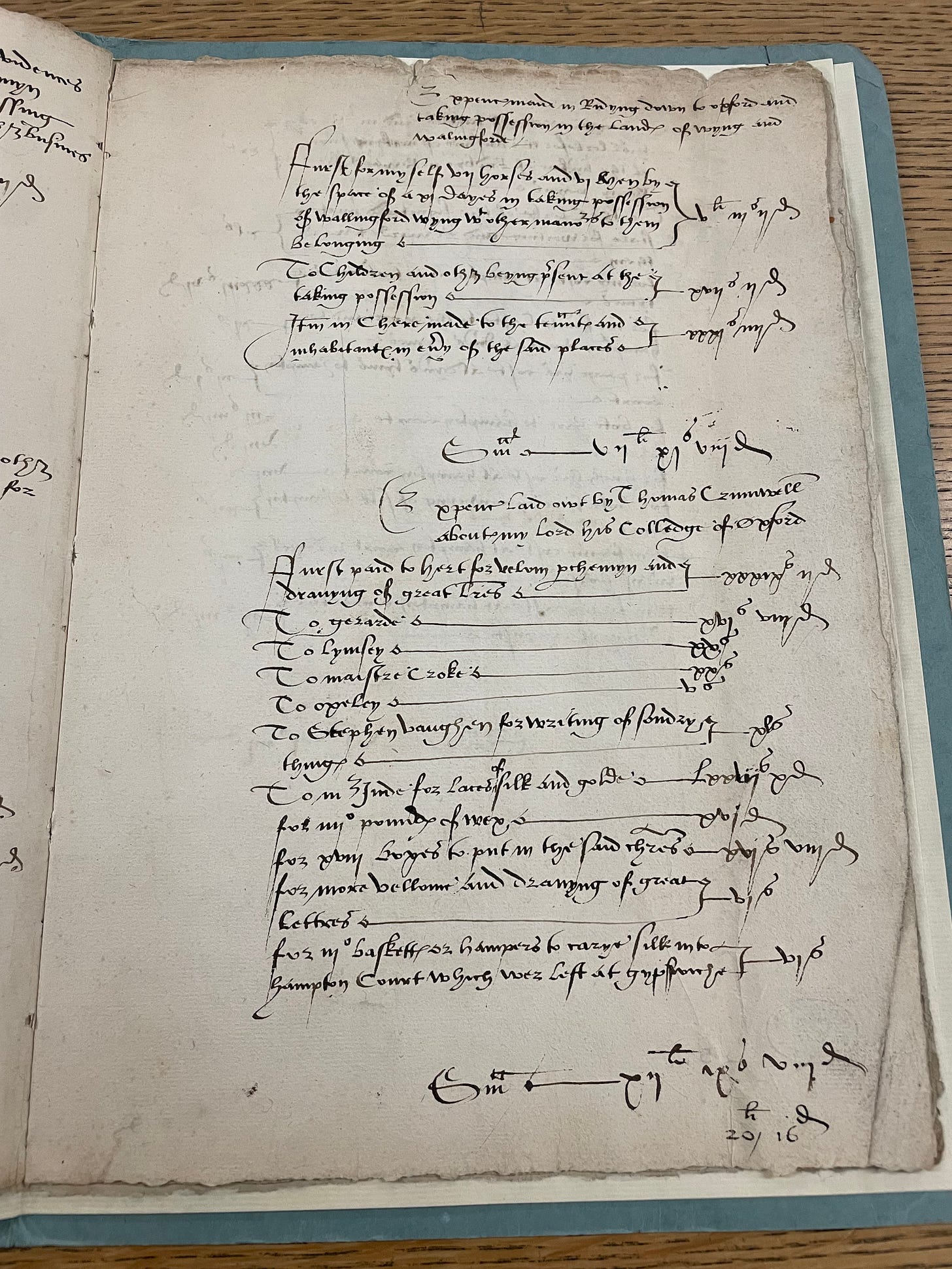

In 1528, Cromwell drew up his expenses for work he had carried out for Wolsey, and this was included in an account book. Account books and inventories are incredible things – they give us glimpses into the intimate lives of households and individuals.

This account book includes a section headed ‘Expenses laid out by Thomas Cromwell about my Lordship’s College in Oxford.’ Clearly, Cromwell paid for Wolsey’s work out of his own pocket, and waited for reimbursement.

He claimed expenses for vellum and parchment; for making payments to various clerks for writing – including one Stephen Vaughan, who plays a significant role later in the trilogy; for boxes in which to keep the College Charters; for baskets to carry silk from Ipswich to Hampton Court.

Cromwell’s handwriting is notoriously bad – almost impossible to decipher. Perhaps this reflects his enormous workload. Or perhaps he didn’t want anyone else to be able to read his notes. This list of expenses is fairly legible, so I believe it was written by one of the clerks who worked for him or Wolsey.

—

Read more about Bea’s Cromwelling at The Thread of Her Tale

The Haunting of Wolf Hall

Wolf Hall is a ghost story. We don’t often talk about this. We are too taken up by the intrigue of the Tudor court and the barbed conversation in candlelit halls. Mantel’s books get shelved as historical fiction, where they twitch uneasily beside bodice and hose, ruff and rapier.

But what matters to me about these books is not so much the act of bringing the dead back to life. A remarkable accomplishment, for sure. What fascinates me most is the capacity of these books to haunt the living. The magic of Mantel is to make dead ink seem more alive than your blood and breath.

Words that can unnerve and unbone you. Fillet the reader, thumbing the page. Words that work as spells to unmake you. Words that do more than tell stories. Although what they’re doing to you, you’re not altogether sure.

How is this done? If anyone really knew how Mantel did what she did, they would have copied her craft and be busy raising the dead. I do not pretend to know how or why Wolf Hall gets under my skin, why these books haunt me. But throughout Wolf Crawl, I will look into the matter. It is partly a study of craft. But it is mostly a literary exorcism, doomed to fail. I want the dead to rest, but the dead have other ideas.

In Wolf Hall, there is a thinning between the worlds of body and spirit. Fact and fiction trade places in some strange shadow dance, reconfiguring into unsettled shapes upon the page. Cromwell writes to Norfolk:

His Grace the cardinal wholly rejects any imputation that he has sent an evil spirit to wait upon the Duke of Norfolk. He deprecates the suggestion in the strongest possible terms. No headless calf, no fallen angel in the shape of loll-tongued dog, no crawling pre-used winding sheet, no Lazarus nor animated cadaver has been sent by His Grace to pursue His Grace: nor is any such pursuit pending.8

He, Cromwell, the lawyer, leaves no clause unwritten in his denial of the cardinal’s sorcery, while making sure to put each dark and twisted creature into Norfolk’s mind, and into ours. A crawling pre-used winding sheet? It wasn’t in my head, but it is now.

Reading Wolf Hall is an aural experience. You hear it as you read it. A vast soundscape that layers itself beyond the small rooms where the drama takes place. So, the narrative continues:

Someone is screaming, down by the quays. The boatmen are singing. There is a faint, faraway splashing; perhaps they are drowning someone.

Noises-off only unsettle us further. Why are there so many sounds in Wolf Hall? Is it because there is so much uncertainty in half-heard things? Is it because, like smell, sound smuggles past our frontal cortex and burrows deep into an ancient part of our mind?

Cromwell picks up his pen. He is not finished:

My lord cardinal makes this statement without prejudice to his right to harass and distress my lord Norfolk by means of any fantasma which he may in his wisdom elect: at any future date, and without notice given: subject only to the cardinal’s view in the matter.

Does he, Cromwell, really write this? It is doubtful. It exceeds his master’s command to ‘just deny it’. But he thinks to write it. And we get to think his thoughts, and parse open a space between the real and the phantasmal, where nightmares breed and ghosts multiply.

And there will be a lot of ghosts ahead of us. I’ll try my best to make a study of them here, and maybe you can help me find the words to settle them back into their sleep. And if not, we can simply share together our own hauntings of Wolf Hall:

This weather makes old scars ache. But he walks into his house as if it were midday: smiling, and imagining the trembling duke. It is one o’clock. Norfolk, in his mind, is still kneeling. A black-faced imp with a trident is pricking his calloused heels.

Quote of the Week: He will take a bet on anything

He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury. He will quote you a nice point in the old authors, from Plato to Plautus and back again. He knows new poetry, and can say it in Italian. He works all hours, first up and last to bed. He makes money and he spends it. He will take a bet on anything.9

The boy of fifteen was good at ‘heavy work’ and could ‘add’. Brains and brawn. But, there is a quarter-century between chapters one and two. It is a lifetime. Where has Cromwell been, and what has he done? For he is now a man of many languages and many talents.

This gap in the story is deliberate. We don’t know a huge amount about Cromwell’s early years. His contemporaries were equally baffled about where he came from. Mantel’s Cromwell is in no rush to tell them, or explain himself. So we must make do with clues: a woman in Antwerp, time as a mercenary in the French army, shadowy recollections of the holy city of Rome:10

‘You don’t understand Rome.’ Wolsey can’t contradict him. He has never felt the chill at the nape of the neck that makes you look over your shoulder when, passing from the Tiber’s golden light, you move into some great bloc of shadow. By some fallen column, by some chaste ruin, the thieves of integrity wait, some bishop’s whore, some nephew-of-a-nephew, some monied seducer with furred breath; he feels sometimes, fortunate to have escaped that city with his soul intact.

The historical novelist begins her real work where the archive peters out. Cromwell’s past and, more importantly, his memory of his past will be a major theme running through all three books, right to our journey’s end.

Next Week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy.

Next week, we read Chapter III. At Austin Friars, 1527 and Part Two, Chapter I. Visitation, 1529. In the UK Fourth Estate edition, this section runs from pages 34–64. In the US Picador edition, it runs from pages 31–59. It begins, ‘Lizzie is still up.’ It ends, ‘my lord won’t be posioned.’

Please use the comments section in this post to discuss this week’s reading and ask any questions you may have. And if you have found it useful, please share this post and podcast to let others know about this slow read.

Credits

I would like to thank Lucie Bea Dutton for bringing the archive to life and

for making maps to help us navigate Cromwell’s world. Thank you Laura Crow for illustrating Wolf Crawl so beautifully. The music is ‘Scaramella’ by Josquin des Prez, arranged for guitar by Joe Bates and performed by Sam Cave. I am your guide, , and this is Wolf Crawl.The southern North Sea and the English Channel were known as the Narrow Seas, the body of water between England and mainland Europe.

York Place was the London residence of the Archbishop of York. It later became the royal palace of Whitehall, and today is the seat of the British government.

Across the Narrow Sea, p. 1.

Across the Narrow Sea, p. 1.

Paternity, p. 17.

Hilary Mantel, ‘The Other King’, The Guardian.

Paternity, p. 21.

Paternity, pp. 32-33.

Paternity, p. 31.

Paternity, pp. 26-27.

Share this post