He sees he need not continue. The indignation on Norris's face is replaced by a look of blank terror. At least, he thinks, the fellow has the wit to see what this is about: not one year's grudge or two, but a fat extract from the book of grief, kept since the cardinal came down. He says, 'Life pays you out, Norris. Don't you find?' [...] Would Norris understand if he spelled it out? He needs guilty men. So he has found men who are guilty. Though perhaps not guilty as charged.

last week | home page | reading schedule

further resources: Hilary Mantel | Wolf Hall

Welcome to Week 27 of Wolf Crawl. I am your guide,

, and this is a year-long slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy: Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies, and The Mirror & the Light.Each week, I dive into the detail with summaries, background, footnotes and tangents to enrich your reading. I am joined on this journey by

, who delves into the archive on our behalf, and Matt Brown, who makes maps to help us find our way through Cromwell’s world.You can find the reading schedule and plot summaries for the full cast of characters on my website, Footnotes and Tangents. There, you can join other slow reads, including Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, and Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, illustrated by a map created by Matt Brown. This week, we are reading the third of five sections from Part Two. Chapter II. Master of Phantoms. London, April–May 1536.

In the UK Fourth Estate edition, this section runs from pages 361 to 406. In the US Picador edition, it runs from pages 302 to 339. It begins, “He has asked the king to keep to his privy chamber,” It ends, “…and picked their own bones clean.”

This summary is followed by a few footnotes of interest.

This week, we speak of revenge and the book of grief. The archbishop repudiates his queen, and they sing bawdy ballads of Jane in the street. We open doors at Carew Manor for the lady in the gable hood with the girdle book, before returning to the Tower to interrogate guilty men. In the archives,

opens the bag of secrets.And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

To get these posts in your inbox or the Substack app, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for ‘2025 Wolf Crawl’ in your subscription settings.

This week’s story

Now we are in dangerous days. We, Cromwell, must keep the king apart and keep him to his course. “Henry seems inclined to obey.” A letter comes from Cromwell’s other self, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer plays his part: “She cannot be guilty. But yet she must be guilty. We, her brethren, repudiate her.”

Down in Surrey, the Seymours are preparing Jane to be queen. She doesn’t know how to open doors, but Cromwell thinks it doesn’t matter. Soon she will have others to open all her doors. Her sister Bess eases her out of French headgear, and into the gable hood she will make her own. At the door, Sir Nicholas Carew reminds the Putney clerk of his obligations to the old families of England.

Bring in Bryan, one-eyed Vicar of Hell, stinking of cheap Gascon wine. He enjoys Sir Francis, who has one foot in the enemy camp. Prepare to be helpful, he says. Ready George Boleyn’s inlaws for what is coming. And tell Carew to get off my back.

In his dark chambers, the King gazes into his glass of truth. Cranmer and Cromwell are there to interpret what he sees. Fitzroy, Henry’s bastard, comes to comfort the King. And afterwards, to press his advantage with Cromwell. The King has no legitimate heirs now, and only one son.

Now to the Tower to put questions to guilty men. Harry Norris, oldest and wisest of the four, can see where this is headed and from whence it came. Gentle Norris says, “you cannot make my thoughts a crime.” But Cromwell wonders out loud: why are you not married, Harry? Are you saving yourself for the queen?

William Brereton: “Turbulent, arrogant, hard-as-nails.” We need not waste time with Brereton. He doesn’t care for justice in his own domain, so why should he expect it here in ours?

George Boleyn: guilty of “pride and elation.” Guilty of crossing Cromwell and not bending with the times. Master Secretary thumbs his soul and finds him complacent. There will always be time for forgiveness. He wants his chaplains, but Crumb is his confessor now.

And Francis Weston. Contrite, ready with remorse. Ready with family money to buy his life. A young man who has not lived, who sees his future dissolve before him. He, Cromwell, has to walk out. He excuses himself. Not for a weak bladder, or to bring in the devices. But because he needs air for his stone heart and racing mind, for the nightmare he has dreamed into being that is now all too real and in the room.

Footnotes

1. Revenge

He sees Norris's eyes move, as the scene rises before him: the firelight, the heat, the baying spectators. Himself and Boleyn grasping the victim's hands, Brereton and Weston laying hold of him by his feet. The four of them tossing the scarlet figure, tumbling him and kicking him. Four men, who for a joke turned the cardinal into a beast; who took away his wit, his kindness and his grace, and made him a howling animal, grovelling on the boards and scrabbling with his paws.

This week, Cromwell interrogates the four gentlemen in the Tower. He makes explicit what has been implicit for some time now: this is revenge for Wolsey.

The Cromwell trilogy is a story of revenge. This is why Wolf Hall begins in 1529 with the fall of Thomas Wolsey. Two episodic prologues in 1500 and 1527 take the Putney boy to Austin Friars and York Place. And then we’re there, behind his eyes, as “they are taking apart the cardinal’s house.” Wolsey’s loyal secretary stands by him, while rats like Stephen Gardiner swim away. He, Cromwell, survives as the cardinal’s house collapses, taking careful note of “where everyone was sitting, at the moment the roof fell in.”

Cromwell has a prodigious memory,”‘a very large ledger. A huge filing system, in which are recorded (under their name, and also under their offence) the details of people who have cut across” him.

In that ledger is a long list of those who brought Wolsey down. Norfolk and Suffolk, “two vengeful grandees.” Norfolk’s niece, Anna Regina, Queen of England. Sir Thomas More, deceased. And the four gloating devils: Brereton, Weston, Norris and George Boleyn. Oh, and a crooked question mark next to Henricus Rex.

As he, Cromwell, rises, he takes the cardinal with him. The choughs on his shield, the turquoise ring on his finger. Now, he reads Norris and the rest, “a fat extract from the book of grief, kept since the cardinal came down.”

Last week, Anne understood. “Cremuel, you have never forgiven me for Wolsey.” Wolf Hall began with scenes of humiliation at York Place and on the river. York Place: the palace Anne took from Wolsey. He thinks, “now Anne Boleyn knows what it is like to be turned out of your house and put upon the river, your whole life receding with every stroke of the oars.”

Mark Smeaton babbled many names in his confession. When he hears Mark say Brereton, he makes sure someone writes it down. But the other names do not interest him, for they do not appear in his own ledger or in his book of grief.

But one name is hard to keep out. Smeaton says it. Carew demands it. Wriothesley queries it. Norris and Brereton are incredulous.

'What about Wyatt, Cromwell? Where is he in this?'

Cromwell promised Henry Wyatt he would protect his son and be a father to him. If revenge against the four devils was easy, saving Sir Thomas Wyatt will be anything but. And it is to that story that we will turn next week.

2. Thomas Cranmer repudiates Anne

You can feel Cranmer shrinking as he writes, hoping the ink will run and the words blur. Anne the queen has favoured him, Anne has listened to him, and promoted the cause of the gospel; Anne has made use of him too, but Cranmer can never see that.

You can read Cranmer’s letter to Henry online. Cranmer is the king’s conscience and the queen’s creature. His betrayal is perhaps Cromwell’s best work. Anne regards herself as indispensable to the “great and marvellous… work of the gospel” that has created “a new England.” And when she is arrested, she calls for “my bishops” and Thomas Cranmer: “He will swear I am a good woman.” But Cromwell has already worked on Cranmer, convincing his better self that “the king does not need Anne” to “maintain the church.”

This letter haunts the future for a time when Cranmer must write again to his king on the matter of a friend in the Tower, in the closing pages of The Mirror and the Light.

3. Ballads against Jane

‘There are rumours on the streets, and crowds who want to see her, and ballads made, deriding her.’

Hilary Mantel has Cromwell inform the king of these ballads. We have the letter that Henry wrote to Jane, warning her about these songs and praying her “to pay no manner of regard to it.” He writes that those responsible will be “straitly punished”, which are the same words Mantel puts in Henry’s mouth when addressing Cromwell.

This letter also refers to “a token of my true affection for thee” and so Mantel imagines that it is Cromwell himself who goes down to Surrey to present this note and gift to Jane Seymour.

4. The Carew Manor at Beddington Park

The walks are coming into their early summer glory. Birds twitter from an aviary. The grass is shorn as close as velvet pile. Nymphs watch him with stone eyes.

Jane Seymour is being kept discreetly away from court at Carew’s house in Surrey. The Carew Manor still stands in Beddington. Cromwell notes “its great hall especially splendid and much copied.” Nicholas Carew’s father built the hall with its impressive hammerbeam roof, similar to the one at Wolsey’s Hampton Court:

Cromwell mentions that Carew “brought Italians in to replan the gardens.” Carew’s son, Francis, will later plant some of the first orange trees in England in this garden. I can’t find the exact quote, but at one point in the novels, Mantel’s Cromwell muses about growing oranges in his own gardens.

The house later became the Royal Female Orphanage and is now a school for children with additional learning needs.

5. Jane Seymour’s Gable Hood

She stands back to assess her daughter, now imprisoned in an old-fashioned gable hood, the kind that hasn’t been seen since Anne came up.

And what a fabulous scene this is: Bess Seymour looking “as if she is attacking her sister”, removing the French headgear and building the elaborate fortified headdress of the gable hood. Their mother Margery, looking on, “grimly triumphant, like a woman who has squeezed success from life, though it’s taken her nearly sixty years to do it.”

We know that Henry’s courtiers thought Jane to be plain and not a beauty. But she loved clothes (remember the kingfisher sleeves) and had a lavish wardrobe. Her portrait by Hans Holbein draws our attention to the beauty and quality of her garments.

Later, when she is queen, the Earl of Bedford will write:

…the richer she was in apparel, the fairer and goodly lady she was and appeared; and the other was the contrary, for the richer she was apparelled, the worse she looked.

The other was Anne Boleyn. And everything is being done to make Jane the mirror opposite of the outgoing queen. Mantel shows her fussing family affecting this transformation. But Mantel’s Jane Seymour is no meek shrew; no puppet of ambitious men. Throughout Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, Mantel hints at a quietly ambitious mind behind that demure and innocent face. When Cromwell asks her what she wouldn’t do to ruin Anne, she is sharp as tacks:

Jane considers: but only for a moment. 'No one need contrive at her ruin. No one is guilty of it. She ruined herself. You cannot do what Anne Boleyn did, and live to be old.'

Cromwell alone has never underestimated Jane Seymour. In his way, he has admired all three of Henry’s wives, if for different reasons. Like his own arranged face, Jane has perfected the art of showing the world what it wants to see, while keeping private the book of her heart. He thinks she has studied the “painted silver-faced virgins” of the Florence masters, “their eyes turned inwards, to images of pain and glory.”

French hood, gable hood, it is not enough. If Jane could veil her face completely, she would do it, and hide her calculations from the world.

6. Girdle books

He produces from among his papers a tiny, jewelled book: the kind a woman keeps at her girdle, looped on a gold chain. ‘It was my wife’s,’ he says. Then he checks himself and looks away in shame. ‘I mean to say, it was Katherine’s.’

Henry is always forgetting who he was married to and whether they were really queens. “Three presents, three wives, and only one jeweller’s bill.” Henry’s father was infamously tight-fisted, and it appears his son has inherited some of Henry VII’s thrifty habits.

At the British Library, there is a girdle book long thought to have been worn by Anne Boleyn:

Could this be the book Mantel has in mind? Well, possibly. However, recent research has revealed a manuscript mix up between this and a lost girdle book that was inherited by the Wyatt family. Curator Eleanor Jackson speculates that the smiling portrait of Henry VIII pictured here may have been added in the nineteenth century to help validate the Anne Boleyn story.

7. Lord Morley

‘My Lord, I shall say, I come myself to spare you a shock – your daughter Jane will soon be a widow, because her husband is to be decapitated for incest.’

A quick note on Henry Parker, 10th Baron Morley, father of the meddlesome Jane Rochford, Anne’s sister-in-law. Francis Bryan has “a dread of Lord Morley” because he is something of a towering Tudor intellect. He had translated Plutarch, Seneca and Cicero into English. He is the only Englishman to have been drawn by the German artist Albrecht Dürer:

But he has another unusual distinction: he served on every jury of lords for cases of high treason during the reign of Henry VIII. So we will meet him again when his son-in-law, George Boleyn, is brought to trial.

8. Henry the theologian

'Repetition of false teachings does not make them true. You agree, Cranmer?'

Just kill me now, the archbishop's face says.

Henry is disposed to retreat into matters of religion whenever he is between wives and needled with doubt. It is worth remembering that he was his father’s second son, raised for the church and not the throne. He has already written against Martin Luther, with some help from Sir Thomas More. Now he has an archbishop with Lutheran inclinations who would quite like to melt into the night, away from his king’s awkward questions.

9. Guilty men, a refresher course

He needs guilty men. So he has found men who are guilty. Though perhaps not guilty as charged.

We first met Harry Norris in Week 2, “the man who hands the diaper cloth”, Groom of the Stool, riding to Wolsey with a ring and “words of comfort” from the king. Wolsey fell on his knees before Norris to thank God. Cromwell “can never wipe that scene from his mind’s eye.” That blot alone seems enough to get Gentle Norris killed.

William Brereton appeared first in Week 7, “old enough to know better” as he removes his devil’s mask. Cromwell notes on a number of occasions that Brereton has a habit of being in two places at once, and one of those places is always near the queen.

No sooner had George Boleyn appeared as a devil in Week 7, we heard the London gossip about his incest with Anne Boleyn in Week 9. That was 1531, five years ago. He is “the blazing noonday planet” who took Cromwell aside to remind him of his place. “I shall profit from this,” said Cromwell. “I assure you sir, and from now on conduct myself more humble-wise.” Well, quite.

And Francis Weston (right handpaw). It wasn’t so long ago that Weston was at Wolf Hall, defaming Cromwell’s dead children, while upstairs, Gregory and Rafe were setting a trap for him with a magic net.

10. William Brereton, King of Cheshire

In my own country, my family upholds the law, and the law is what we care to uphold.

In sixteenth-century England, Cheshire was a county palatine, a region of the kingdom where local magnates operated with very little oversight. It did not send MPs to London, but held its own parliament and had its own legal system. Brereton had amassed titles and positions in the region, becoming the most powerful man in Cheshire and North Wales.

Brereton asks Cromwell why he is here and not Wyatt. It is a good question. The evidence against Brereton is weaker than the rest. He is socially inferior to the other three gentlemen and somewhat peripheral to Anne’s circle. Historian Eric Ives suggests that Cromwell viewed Brereton as an obstacle to his own local agent, Bishop Rowland Lee, and his reform of the government in Wales.

In Mantel’s telling, Cromwell believed Brereton guilty of murdering a local gentleman, John ap Eyton. “But your schemes end here,” Cromwell says. The prisoner replies:

‘You are judge and jury and hangman, is that it?'

'It is better justice than Eyton had.'

And Brereton says, 'I concede that.'

In the archives with Bea Stitches

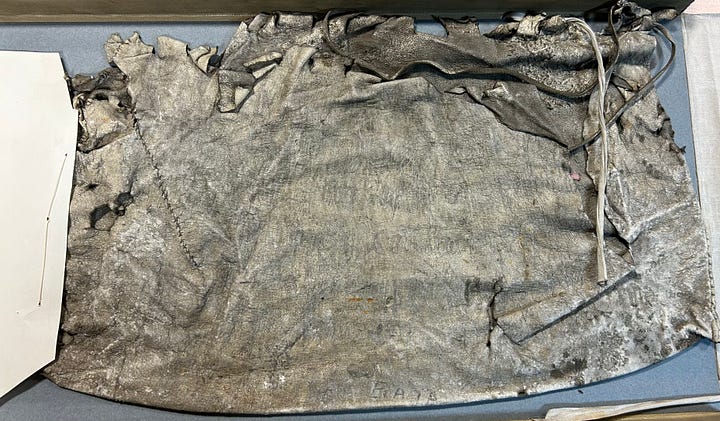

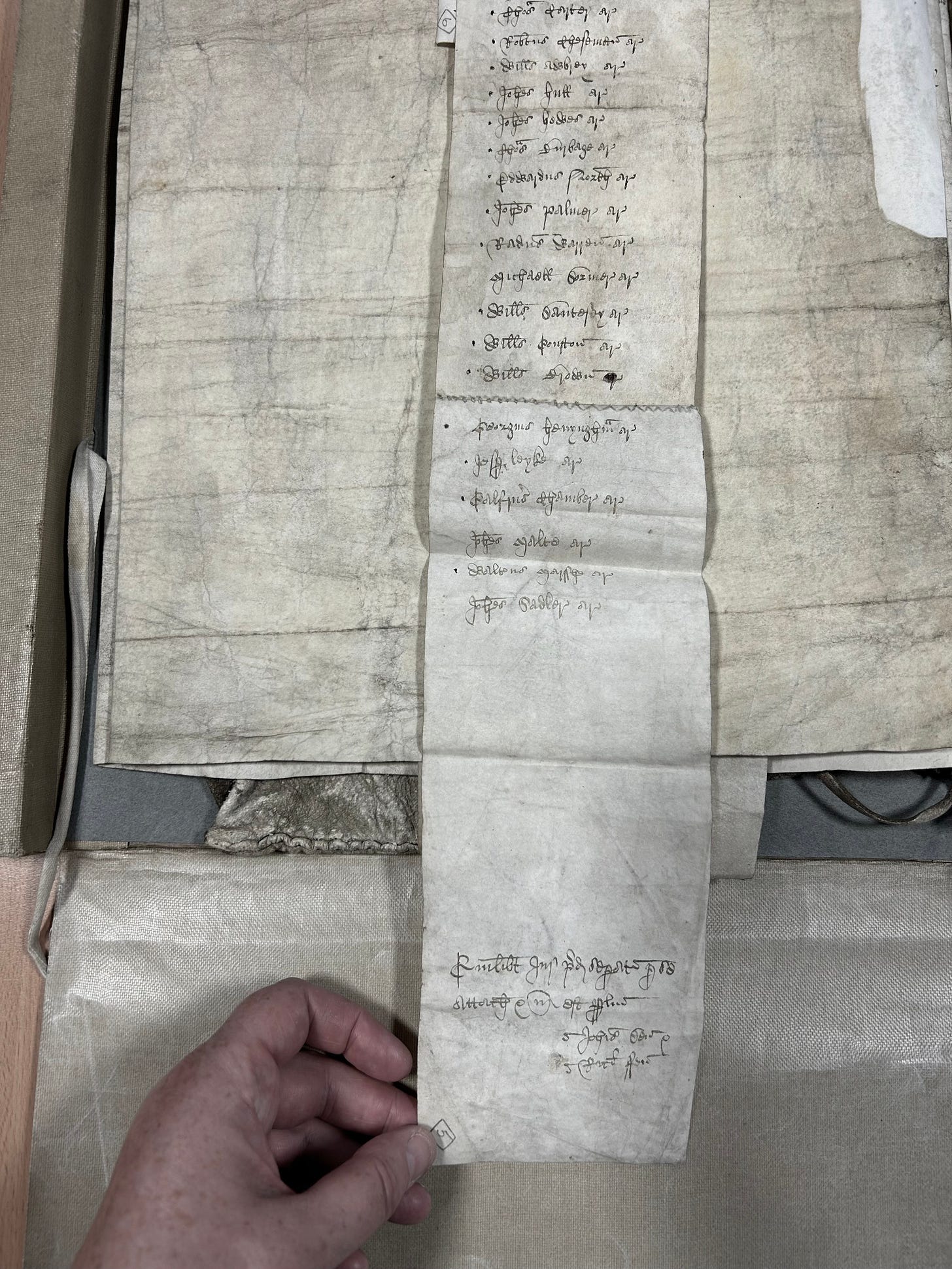

This week, we open the Bag of Secrets. Or to be more accurate, we open a “baga de secretis”. This is literally a leather bag in which sensitive trial documents were placed and then filed, with restricted access. A good description of the history of baga de secretis can be found on the National Archives blog; rather than trying to explain the concept myself, this is the best place to look.

The actual leather bags from some of the baga de secretis trials at the King’s Bench are still in existence – and are stored with the documents they once contained. The documents themselves are no longer in the bags (which are, 500 years on, rather fragile) but are boxed with them.

Some King’s/Queen’s Bench trial documents can be seen in the standard archive reading rooms. I was able to call up the trial documents of both Katherine Howard and Anthony Babington as part of a general day’s archive activity (I explain my fascination with the Babington Plot in this post). But if you want to look at certain trial documents from 1536, you have to go into a locked room and wait for the papers to be taken out of a safe. You are locked in. You are not allowed to leave the room until the documents have been returned and locked away. You can be watched reading them through a two-way mirror. I suppose these are among the most notorious documents held by the UK National Archives, and are rightly protected.

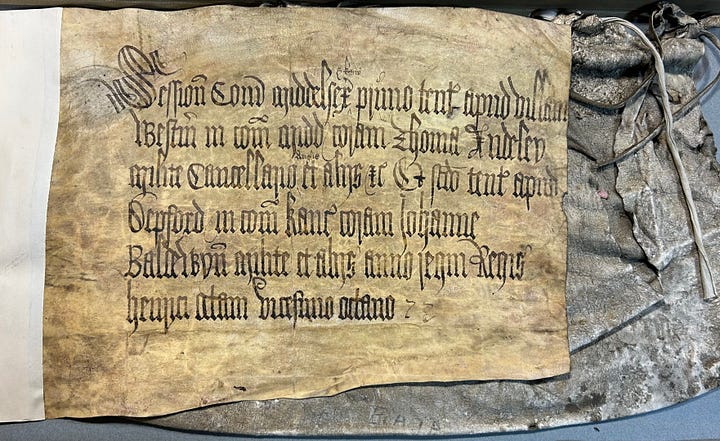

In the locked room, I saw the most upsetting, the most haunted documents I have ever seen: documents relating to the trial of Henry Norris, Francis Weston, William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton in May 1536.

Many of these documents are procedural – and are the formal arrangements for calling for the special commission of Oyer and Terminer (which means to hear and determine) for the County of Middlesex and a grand jury under the direction of the Duke of Norfolk as High Steward of England. So one could see them as simply dry legal documents. But somehow, the lives of the men on trial still seep through.

I found seeing the names of the accused men seriously upsetting. Seeing their names written formally like this brings one face-to-face with what happened to them. It’s no longer a dry fact. It’s the impact of touching the procedures and documents that condemned them.

The Bag contains one document that is stitched together – a list of some sort, too long for one piece of paper, so a second has been stitched to it. As a needlewoman, I like to see stitchery, but this is stitchery with the intent to condemn. In The Mirror and the Light, there’s a line that reads: “It’s useful to have the evidence stitched together.” I can’t help but feel that this is the document that inspired that line.

At the bottom of the page of one of the surviving documents, there are marks. When I first saw these I read them as “TC” and – at that stage being less familiar with Cromwell’s handwriting – I thought that they were his initials, showing his hand on the documents. It is no secret that I like – love? – Hilary Mantel’s version of Cromwell, but here I was coming face to face with the historical record of his involvement in the death of these men. I was very disturbed by this when I was handling the documents.

I know now that these marks are not in Cromwell’s hand. But they are still disturbing, and he is still complicit. The marks mean T&S. This stands for Trahendum et suspendendum – hanging, drawing and quartering. T&S is written four times – for Norris, Brereton, Weston, and Smeaton.

What happened at the trial itself is unclear – the documents do not paint a full picture. We don’t have records of what was said, or what evidence was produced. According to John Guy and Julia Fox’s 2024 book Hunting the Falcon, “the confusion lies in the fate of any preparatory witness statements and pre-trial examinations that once existed but have now disappeared … None of these documents was ever filed in the Bag of Secrets.”

According to Guy and Fox, drawing on an old report of the Keeper of Public Records from 1869, an inventory “made in 1544 of the most important documents” did survive and “lies hidden in an obscure class of rarely produced documents in the National Archives in Kew”.

A reference for these documents is given – but when I called up the documents using this reference, they turned out dates mostly from the eighteenth century, and were not relevant to 1536. I think there must be a typo in the referencing, which is so easily done. I’m back in the archives tomorrow, and I have called up some other documents from this series which look interesting – but so far I haven’t been able to locate the inventory. Of course, I will let you know if I ever see it.

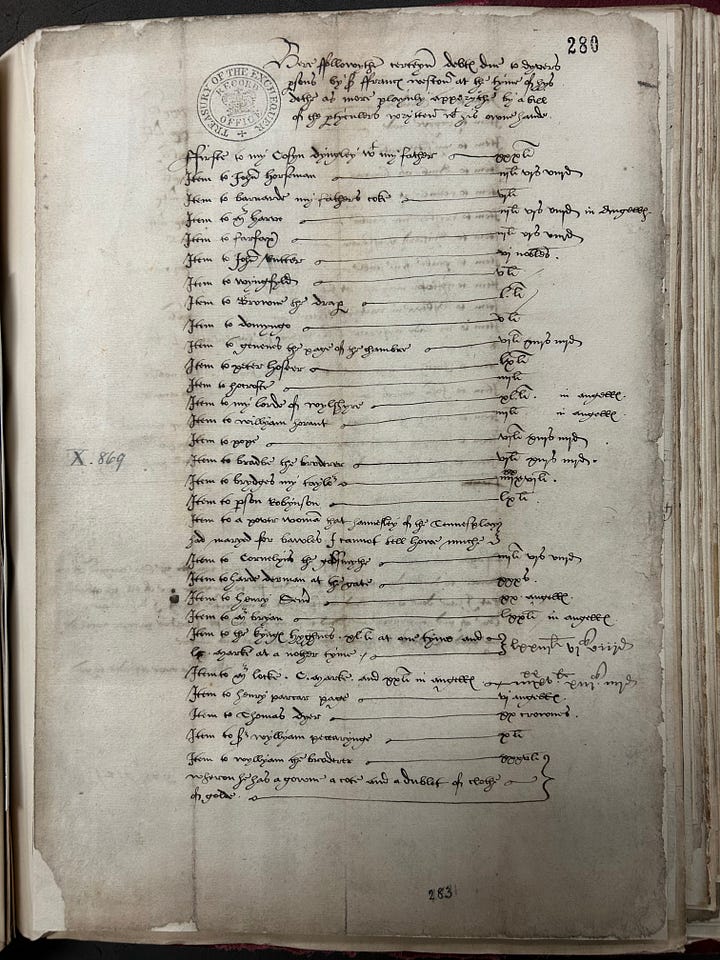

The final document this week is not from the Bag of Secrets, but it’s another horribly upsetting piece. It is a list of Francis Weston’s debts drawn up at the time of his death.

I remember first looking at it at the end of a long day and rushing to photograph it before closing time – and then hearing a voice in my head. It was the voice of Thomas Wyatt, voiced by Ben Miles in the audiobook of The Mirror and the Light. It said, “But Weston was a boy.” And I was reminded of Ben talking about the cast of “Bring up the Bodies” who, during the London run of the RSC production, remembered the men accused on the anniversary of their death, just down the river from the Adelphi Theatre.

Ashamed, I said to myself “these are the debts of a dead man and you should pay proper respect”. I went back to the archive a few days later and spent some focused time with the document.

Weston owed money to many people, including his cousin, his father’s cook Barnarde, Browne the draper, my lord of Wiltshire (Anne’s father), Bradbe the broderer, his tailor Brydges, “a poor woman that Hannseley of the tennis play had married for balls I cannot tell how much”, Cornelius the goldsmith, Francis Bryan, the King, his shoemaker Ambrose Barcar, his barber Crester – and others.

At the end of his list of debts, he wrote:

Father and mother and wife, I shall humbly desire you, for the salvation of my soul, to discharge me of this bill, and for to forgive me of all the offences that I have done to you, and in especial to my wife, which I desire for the love of God to forgive me, and to pray for me: for I believe prayer will do me good. God's blessing have my children and mine.

By me, a great offender to God.

We readers shall not escape these weeks. As Thomas Wyatt would later write: “These bloody days have broken my heart.”

— Bea Stitches

Read more about Bea’s Cromwelling at The Thread of Her Tale

Quote of the week: A wild garden

The last two prisoners are young men. They hoped to become old men. Cromwell tells George Boleyn, “I think you have become too assured of forgiveness, believing you have years ahead of you to sin.” God must be patient while George sins. Francis Weston says, “I have not lived,” and he thinks of the good works he would do, so “God would see I was sorry.”

Not long later, Cromwell excuses himself. The boy Weston talking about being ‘forty-five or fifty’ is a little too much for this fifty-year-old servant of the king. “As if, past mid-life, there is a second childhood, a new phase of innocence.” But of course, no second childhood exists for Cromwell. At fifty, he plays chess with men’s lives and holds the butcher’s knife to a boy’s throat. No wonder Master Secretary needs some air.

Let us say you are in a chamber, window sealed, you are conscious of the proximity of other bodies, of the declining light. In the room you put cases, you play games, you move your personnel around each other: notional bodies, hard as ivory, black as ebony, pushed on their paths across the squares. Then you say, I can't endure this any more, I must breathe: you burst out of the room and into a wild garden where the guilty are hanging from trees, no longer ivory, no longer ebony, but flesh; and their wild lamenting tongues proclaim their guilt as they die. In this matter, cause has been preceded by effect. What you dreamed has enacted itself. You reach for a blade but the blood is already shed. The lambs have butchered and eaten themselves. They have brought knives to the table, carved themselves, and picked their own bones clean.

Next Week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. You can read the 2024 discussion here, and all the contributions to Wolf Crawl are compiled in the complete book guide on my website.

Next week, we will read the fourth of five sections from Part Two. Chapter II. Master of Phantoms. London, April–May 1536. In the UK Fourth Estate edition, this section runs from pages 406 to 441. In the US Picador edition, it runs from pages 340 to 369. It begins, “May is blossoming…” It ends, “If ever a man came close to beheading himself, Thomas More was that man.”

Please use the comments section in this post to discuss this week’s reading and ask any questions you may have. And if you have found it useful, please share this post and podcast to let others know about this slow read.

Credits

I would like to thank Lucie Bea Dutton for bringing the archive to life and

for making maps to help us navigate Cromwell’s world. Thank you Laura Crow for illustrating Wolf Crawl so beautifully. The music is ‘Scaramella’ by Josquin des Prez, arranged for guitar by Joe Bates and performed by Sam Cave. I am your guide, , and this is Wolf Crawl.

Share this post