To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for the Cromwell Trilogy.

Welcome to week 30 of Wolf Crawl

As we start a new book this week I am excited to announce a new feature on Footnotes and Tangents. If all goes well, this post will be published as an email newsletter, an online post and now a podcast to download or stream online. Just search for The Wolf Crawl Podcast or copy the rss feed in this post. And let me know if it works and what you think.

This week, we are reading the first chapter of The Mirror and the Light, ‘Wreckage (I) London, May 1536’. This runs from page 3 to page 25 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Once the queen’s head is severed, he walks away.’ It ends: ‘It is 20 May 1536.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

It is 20 May, and, already this year 1536, two queens are dead. Anne’s head is severed and put at her feet in an arrow chest. He, Cromwell, thinks of his second breakfast while he admires the headsman’s sword. We knelt when the queen died, but Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, did not. Neither did Richmond, one of the king’s three illegitimate children.

At breakfast, Master Secretary is bombarded with questions. He tells the assembled that Jane will take the motto, Bound to Obey and Serve. Brandon laughs. Norfolk declares his loyalty with a little too vigour for a man of sixty. He treats us like a comrade, but do not be deceived: Thomas Howard is not our friend.

He takes his nephew, Richard Williams alias Cromwell, to see Thomas Wyatt – the prisoner-poet in the Tower. Everyone loves Wyatt, and Martin, the gaoler, has fallen under his spell. Wyatt’s evidence was not needed in court and he, Cromwell, gives it to Wyatt to destroy. Going out, Richard asks whether it is over. ‘Over?’ he says. ‘Oh, no.’

At home, Rafe Sadler greets him. His wife, Helen, wonders who will protect the gospel in England now the queen is gone. ‘I can protect it better,’ he says; he, Thomas Cromwell. On his desk, an ambassador’s letter to decipher. Chapuys rejoices with his master, Emperor Charles, as the heretic concubine lives her last hours.

Thomas Wriothesley, Call-Me Risley, comes in. He tells him to move against Norfolk, while he still can. He tells him the old families will expect the king’s daughter, Mary, to be made heir. He says people are asking which of the cardinal’s enemies, Thomas Cromwell will next destroy.

Outside, his household hunts a Damamascene cat, loose in the garden. Inside, he and his nephew drink to his health and the confusion of their enemies. At night, he relives the three heartbeats that finished Anne Boleyn. It is 20 May 1536.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Francis Bryan • Charles Brandon • William Kingston • Gregory • Earl of Richmond • Norfolk • Richard Cromwell • Martin • Thomas Wyatt • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Wriothesley • Christophe • Nicholas Carew • Dick Purser

This week’s theme: What he never knew

If you have just finished reading Bring Up the Bodies, you may notice something rather curious about the first chapter of The Mirror and the Light: we have re-run the closing scenes of the second book in the trilogy. And a key scene between Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Wriothesley has been entirely rewritten.

Now, the prosaic explanation is that eight years have elapsed between the writing of the two books. This is a recap: a helpful reminder of where we are. Previously… on Wolf Hall. But I think there is a much more interesting reading to be had.

These books are about memory. Cromwell, Mantel reminds us, ‘is famous for his memory… The only things he cannot remember are the things he never knew.’ The problem with a prodigious memory is you can’t forget, even if you want to. However hard you try to escape the past, it comes at you with a big net. The past is the land of the dead, and the ghosts are gathering. In the cast of characters, you will find, first and foremost, ‘the recently dead.’

So, one reason we return to the moment of Anne’s death is that Cromwell will continue to relive these ‘three heartbeats.’ He dreams about it in panels. In the second, Anne wears a white cap, as his wife Liz did when last he saw her alive. Or rather, when he thought he saw a flash of her white cap on the stairs. It was a false memory; it was a ghost.

Cromwell would like to think that memory is a precise imprint of the past. Throughout these books, Hilary Mantel disrupts that certainty. Every time we remember, we reconstruct events to fit a fresh understanding and purpose.

In The Mirror and the Light, we will replay many memories familiar from the first two books. Each time, we will be mindful of what has changed. You will have noticed that this book is the longest of the three by far. And with good reason: we now carry with us all the memories of a man of fifty who has lived many lives. Each second lived now, in May 1536, disturbs all those devils and demons we thought we had left behind.

Footnotes

1. Walking on a knife-edge

The man turns away and begins cleaning his sword. He does it lovingly, as if the weapon were his friend. 'Toledo steel.' He proffers it for admiration. 'We still have to go to the Spaniards to get a blade like this.'

Toledo steel had been famous for centuries. Hannibal armed his Carthaginian soldiers with weapons forged in Iberia during the Second Punic War against the Roman Empire. Charlemagne, the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, and their grandson Emperor Charles V all owned swords made of Toledo steel.

Mantel uses the moment to remind us of Cromwell’s baseborn beginnings:

You would not guess it to look at him now, but his father was a blacksmith; he has affinity with iron, steel, with everythhing that is mined from the earth or forged, everything that is made molten, or wrought, or given a cutting edge.

There is a sharpness to the writing in this chapter. Anne’s decapitation is likened to such ordinary things as a ‘sigh’ and ‘scissors through silk’. Meanwhile, he visualises Thomas Wyatt ‘swaying, on the spike’ before his nephew looks ‘at the nape of his bent neck’ and rubs his shoulder, ‘friendly and firm like a man with his favourite dog.’ It often feels as though a sharp edge may come out of nowhere, from friend or foe.

‘My uncle has walked a knife-edge for you,’ Richard tells Wyatt. These have been trying days for all of us: a high-wire balancing act, like a cat up a tree. Call-Me, ‘nervous as a hare,’ says the Cromwells are trying to frighten him. ‘You are making me pick my way through thorns.’

And we’re not safe yet. Not even close. The old families are out to get us, and so is Stephen Gardiner. Uncle Norfolk eyes ‘the Cromwell bull-neck. He is wondering what sort of blade you’d need, to slice through that.’

Further reading:

Toledo’s last swordmakers refuse to give up on their ancient craft

Chilling find shows how Henry VIII planned every detail of Boleyn beheading

2. Speaking truth at a beheading

Gregory had said he could not do it, when told he should witness her death: ‘I cannot. A woman, I cannot.’ But his boy has kept his face arranged and his tongue governed. Each time you are in public, he has told Gregory, know that people are observing you, to see if you are fit to follow me in the king’s service.

Much of Wolf Hall dealt with how to hide our true feelings behind a perfect performance of our public self. Gregory is learning this art, alongside the art of public speaking, but he doesn’t think he will ever master it: ‘when to speak and when to keep silence.’

Indeed, Gregory says too much in this chapter. He asks questions of the Earl of Richmond, and betrays to Norfolk what the Cromwells do behind noble backs. Cromwell has to step in to silence the boy, as he later has to stop Thomas Wyatt from speaking himself onto the scaffold.

But he himself is not immune from indiscretion. Imitation and instinct lull you into letting your guard down: he almost crosses himself as Anne’s head is parcelled into the arrow chest. And he fakes anger with Charles Brandon, only to let his emotions get the better of him:

'I stand just where the king has put me. I will read you any lesson you should learn.' He thinks, Cromwell, what are you doing? Usually he is the soul of courtesy. But if you cannot speak truth at a beheading, when can you speak it?

He’s not angry with Brandon. But he cannot resist the opportunity to put ‘the mighty fellow with the big beard’ in his place. That place is below him, the boy from Putney, who has risen above the peers of the realm.

3. The imprint of the past

The beheading brunch is a buzz with questions:

When will Jane do us the honour? When may we notify the painters and artificers and set them to work? Will there be a coronation soon?

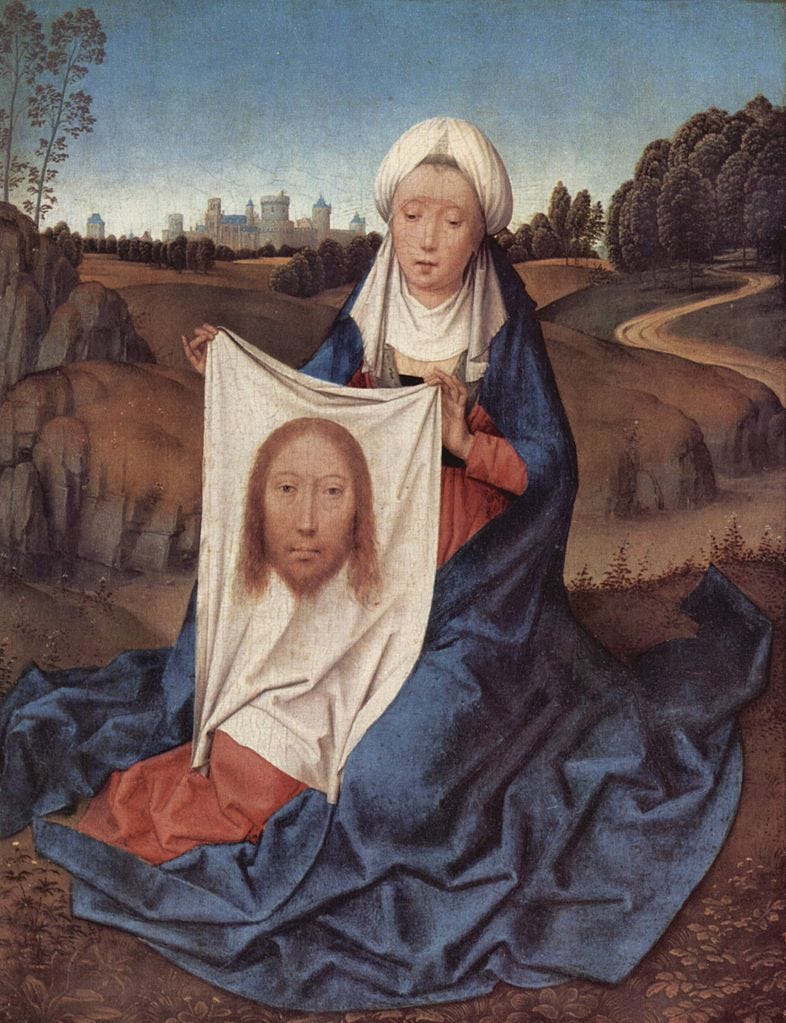

Jane Seymour was never crowned. Plague in London postponed any plans, and her husband was probably also waiting for that all-important male heir before sealing the deal. But the future is a ‘curious blank’, and we hope for a fine day of festivity and pageantry. The dignitaries propose to rummage around in the store cupboard from Queen Katherine’s time. They have ‘St Veronica in panels.’

According to tradition, Saint Veronica offered her veil to Christ to wipe his face as he carried his cross to Calvary. When he returned the veil, it bore an imprint of his likeness. The veil became a relic, reportedly held in the Old St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

You may remember Cromwell hearing of the sack of Rome in 1527. According to some reports, this was when Veronica’s veil was looted by German soldiers and passed around the taverns of Rome.

Fabrics of all kinds play a part in our story. And Cromwell dreams that Anne is like the crucified Christ, although he is too dazed from waking to see whether her face is reproduced on the cloth. But one thing is certain: the image of her head, that ‘soaking parcel’, is imprinted on his memory.

St Veronica is the patron saint of those memory printers, the photographers. One book you should consider consulting alongside The Mirror and the Light is The Wolf Hall Picture Book. This is a collaborative project by Hilary Mantel, the actor Ben Miles (who played Cromwell on stage and reads the audiobooks), and his brother, the photographer George Miles.

The picture book is a series of images of modern London following the footsteps of Cromwell from Putney to Tower Hill. Here, the past seeps into the present. The Miles brothers clearly recognised and understood what Mantel was doing in these books: not just recreating Tudor England, but exploring how our sense of self, place and Englishness is filtered through our imagining, remembering and forgetting of our past.

The Wolf Hall Picture Book includes quotes from the three novels and ‘deleted scenes’ from The Mirror and the Light. I’ll try to bring a few of these into the discussion as we proceed with our slow read.

Further reading:

4. The Damascene cat

‘Letter from Nicholas Carew,’ Richard says. ‘And by the way… the cat’s out again.’

This, for me, is the moment when this book comes to life. Page 20: enter the Damascene cat. This is what Mantel’s writing is all about: private and public worlds entwined; a conversation about politics and statecraft, cheek-by-jowl with the everyday problem of a cat stuck up a tree.

Mantel reminds us that Cromwell had a cat back in Wolf Hall. Marlinspike was the cardinal’s. The historical Thomas Wolsey was indeed fond of felines, bringing them to meetings and royal processions despite their association with witchcraft and sorcery. Or maybe, because of them? A love of cats is another way Mantel’s Cromwell continues Wolsey’s legacy.

Cats of all kinds have crept up on us during our reading. Thomas Wyatt’s father, Sir Henry Wyatt, told the story of a cat that brought him a pigeon to eat when locked up by bad king Richard III. The elder Wyatt was then almost killed by a pet lion and was only saved by his son, Thomas. On remembering that story, Thomas Wyatt said it did not seem like the sort of thing he would do. It was more like something Thomas Cromwell might do.

In Bring Up the Bodies, a dead Thomas More reminds the living Thomas Cromwell that being merry with the king is ‘like sporting with a tamed lion. You tousle its mane and pull its ears, but all the time you're thinking, those claws, those claws, those claws.’

Cromwell has purchased his current cat for ‘a price you would not believe’: another example of his extravagant and conspicuous consumption. Gregory, with a net in the garden, recalls to us him and Rafe Sadler hunting a phantom Francis Weston at Wolf Hall at the start of Bring Up the Bodies. But the cat is no preening courtier. This striped beast is Cromwell’s own feline familiar:

I have risen above this, he thinks: this day, this waning light, these snares. I am the Damascene cat. I have travelled so far to get here, and nothing they do disturbs me now, nor disquiets me, high on my branch.

Trees, stairs, ladders, wings: we will pursue these rising images through The Mirror and the Light. The story that began on the cobbles has now reached dizzying heights: ‘Though he is a commoner still, most would agree that he is the second man in England.’

Thomas Cromwell makes Call-Me nervous: ‘Norfolk is against you, the bishop is against you, and now you are going to take on the old families as well. God help you, sir. You are my master. You have my service, and you have my prayers.’

So, who will bring Cromwell down? Who will catch the cat?

He imagines the world below her: through the prism of her great eye, the limbs of agitated men unfurl like ribbons, yearning through the darkness. Perhaps she thinks they are praying to her. Perhaps she thinks she has climbed up to the stars. Perhaps the darkness falls away from her in flecks and sparks of light, the roofs and gables like shadow in water; and when she studies the net there is no net, only the spaces between.

Further reading:

5. Wriothesley’s question

There are a lot of questions flying around in this first chapter. This is what making history feels like: ‘the future is a curious blank’ as no one has ever executed a queen before. Even Thomas Wyatt, so good with words, has only blank pages to show for a night’s torment in the Tower.

However, one question troubles Cromwell more than the rest. It is Call-Me’s question, and we heard it first last week. Really, it comes from Stephen Gardiner because, as Richard Cromwell says, ‘who but the bloody buggering Bishop of Winchester would come up with a question like that?’

If Henry Tudor was Cardinal Wosley’s greatest enemy, ‘what revenge will Thomas Cromwell seek on his sovereign, his prince?’

Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell is driven by ambition, by revenge, and by a belief in a better world. But I don’t think he knows which of these three impulses is stronger, or which will do for him in the end.

And yet Wriothesley’s question seeps into him, and leaves in his mind a chilly trickle of dismay, like water creeping into a cellar. He is shocked: first, that the question can be asked. Second, because of who asks it. Third, that he does not know the answer.

The Haunting of Wolf Hall

Paid subscribers can read the latest instalment of my exploration of spectral themes in the trilogy:

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. You can now read complete guides to both Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies on my website.

Next week, we start the first section of ‘Salvage, London, Summer 1536’ This runs from page 27 to page 77 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Where is my orange coat?’ It ends: ‘…feeling as if for the first time the beat of his own heart.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip on Stripe. These always make my day and reminds me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Further notes on the Veil of Veronica. The allusion is interesting: if the relic and miracle is true it would be one of the few (only?) true visual representations of Christ. We have no contemporary portraits of Anne Boleyn so we cannot be sure what she looks like. And of course, that question about how true the copy (fiction) is to the past (fact) is central to Mantel's work.

Further notes on the title: I didn't mention it in the post, but the chapter title Wreckage references Call-Me's comment at the end of Bring Up the Bodies. Cromwell tells him that you can use wreckage. It is then interesting that this conversation has been rewritten at the start of this novel, almost as though Mantel has herself taken the wreckage and created something new.