Welcome to week 26 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 3, Part 1, Chapters 11 – 17.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. By upgrading to paid or making a one-off donation, you allow me to keep making these posts.

Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: Growing Pains

When I first read War and Peace, I didn't care for the Rostovs. Two spoilt rich kids who discover life is no bed of roses? That didn’t sound compelling to me.

Pierre and Andrei seek the meaning of life. They have grand epiphanies and make life-changing decisions. In comparison, the stories of Nikolai and Natasha seemed muted, incremental and incomplete.

But as I have grown older, I have warmed to the Rostov siblings. Their family name is derived from the verb rosti, which means ‘to grow.’ And that is what they do. Subtle, unspectacular changes that unfold over hundreds of pages. Life's moments layered upon each other, pressing down and forcing up.

As Nikolai recognises in chapter 14, "only time" can do this. When you look back on who you were ten years ago, you realise that without conscious effort, you have become a different person.

The demons the Rostovs face are commonplace: pride, vanity, cowardice, anger, impatience, naivety. They overcome one, only to fall back into another. Which often looks a lot more like real life than Andrei's infinite skies or Pierre's blazing comet.

At the beginning of volume three, Tolstoy asks who makes history? One man or a million? Society or the individual? He then turns to the Rostovs: How did they get into the mess they're in?

Nikolai's medal of honour and Natasha's badge of shame are supposedly the results of their own actions. But it was a militaristic and patriarchal society that decided who would be honoured and who would be shamed. Both are overcome by remorse. One is promoted. The other is made sick.

"I can't make it out at all," thinks Nikolai.

His honest confusion is relatable. Life often doesn't make sense. And we might conclude that it doesn't matter what we do, or who we are, because society will do with us what it will. Except society misleads and misdirects.

It makes Natasha mistake Pierre's love for pity. And it makes Nikolai unable to distinguish between the shame of trying to kill a man, and the compassion that meant he did not.

We see, but we don't see. And like this, we grow.

Chapter 11: The Myth of Genius

Andrei listens to the generals argue about strategy and tactics, feeling sorry for the selfless but self-confident Pfuel, whose day is clearly done. Andrei notes ‘a panic fear of Napoleon’s genius’ that did not exist before. But more than ever, he is convinced that war is not won by generals and military genius but by the man in the ranks who holds his nerve. So, he asks the emperor for permission to serve on the frontline.

Andrei • Pfuel • Alexander • Bennigsen

What do you think about Andrei’s respect and pity for Pfuel? Despite his criticisms of the ideas, does he recognise himself in Pfuel?

Do you have trouble separating Tolstoy’s and Andrei’s opinions in these chapters?

Without pity or love

At the beginning of the novel, Andrei believed in the science of war. He thought Napoleon was its greatest theoretician and practitioner. That was before Austerlitz and before the Pfoolish Pfuel:

Not only does a good army commander not need any special qualities, on the contrary he needs the absence of the highest and best human attributes—love, poetry, tenderness, and philosophic inquiring doubt. He should be limited, firmly convinced that what he is doing is very important (otherwise he will not have sufficient patience), and only then will he be a brave leader. God forbid that he should be humane, should love, or pity, or think of what is just and unjust.

So perhaps successful warriors should be pitied rather than admired? Disgusted by the delusions of generals, he again gives up his promising career and heads to the front. A decision with no small consequence for the life of Andrei Bolkonksy.

Chapter 12: Rostov the Wise

In 1812, Nikolai Rostov is back with his regiment where he has been promoted to captain. He writes to Sonya to say he will fly to her once the war is over. Despite the depression and unease at headquarters, Rostov and the army are merry and content. Nikolai has a young acolyte, Ilyin, and a newfound scepticism regarding stories of heroism. Together, they set out to a tavern where their comrades are relaxing with the doctor and his wife, Marya Gendrikohovna.

How has Nikolai grown? How has he stayed the same?

What do you think about his plans for the future?

Good stories

An officer with a long moustache speaks “grandiloquently of the Saltanov dam being ‘a Russian Thermopylae’”. This is a reference to a battle fought in 480 BC between the Persian Empire and an alliance of Greek states led by Sparta under King Leonidas I. It is often held up as an example of heroic self-sacrifice, a resilient last stand against an invading army of overwhelming numbers.

Nikolai told his own farfetched stories to Andrei and Boris after Schöngrabern and Tolstoy had noted that it is almost impossible for us to tell the truth when relating these moments of intense emotion and action. Now, Rostov is sceptical of stories, and what he thinks but does not say tells us an enormous amount about his development:

‘And why expose his own children in the battle? I would not have taken my brother Petya there, or even Ilyin, who’s a stranger to me but a nice lad, but would have tried to put them somewhere under cover,’ Nikolai continued to think, as he listened to Zdrzhinsky. But he did not express his thoughts for in such matters, too, he had gained experience. He knew that this tale redounded to the glory of our arms and so one had to pretend not to doubt it. And he acted accordingly.

Chapter 13: Marya Gendrikhovna’s Hands

In the tavern, a group of officers sit drinking tea and flirting with Marya Gendrikhovna. Her husband sleeps as they ask her to stir their tumblers with the only spoon. They propose to play cards for the honour of kissing her hand. But the doctor wakes up, and he takes his wife to sleep in their cart. The rest lie in the tavern, exchanging conversation and merry childlike laughter.

Did the soldiers act inappropriately with Marya Gendrikhovna?

What do you think she was thinking?

Hands: the soul in action in the world?

There were only three tumblers, the water was so muddy that one could not make out whether the tea was strong or weak, and the samovar held only six tumblers of water, but this made it all the pleasanter to take turns in order of seniority to recieve one's tumbler from Marya Gendrikhovna's plump little hands with their short and not over-clean nails. All the officers appeared to be and really were in love with her that evening.

Our discussion for this chapter was interesting because there are contrasting opinions about the mood and meaning inside the tavern. You can read this scene as endearing, with homesick and fearful soldiers distracting themselves in the company of a charming woman, who beams with satisfaction as her husband slumbers. Or you can sense an underlying menace and the precarious and dangerous position of a woman in wartime. I think this chapter expertly navigates the ambivalence and ambiguity of the situation.

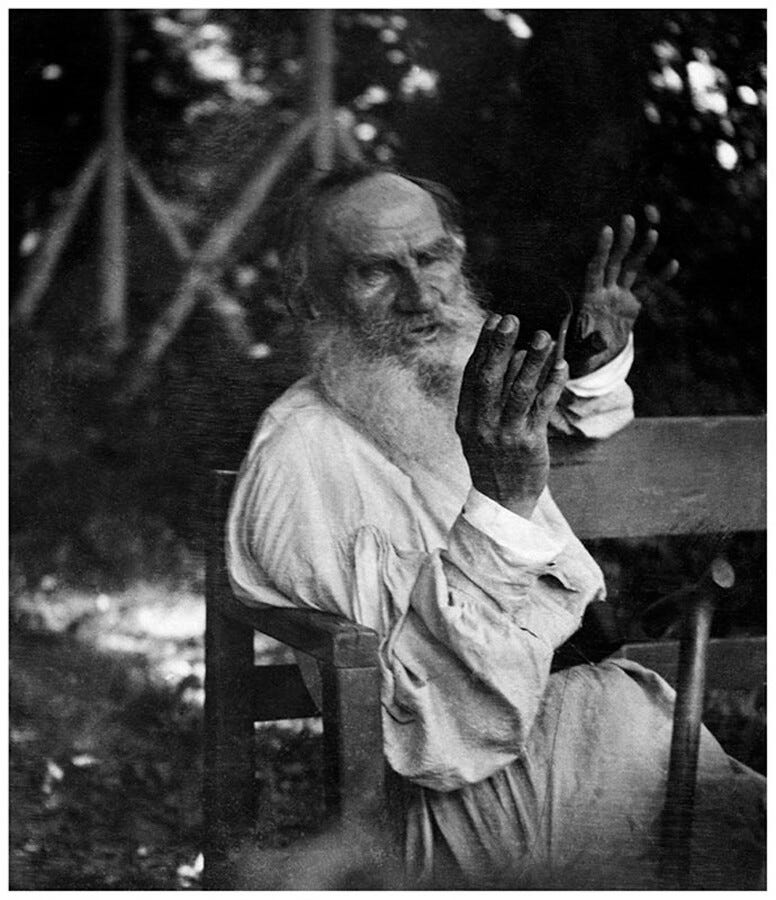

And what do you make of those ‘not over-clean nails’? Tolstoy is drawn to hands as much as he is to describing eyes and mouths. If eyes are windows to the soul, what are the hands? We are the creature that has made the best use of our forepaws, so do hands make us human? Surrounded by mud and dirt and death, chasing human feelings of fear out of their heads, do these soldiers look to Marya Gendrikhovna’s hands as something fundamentally familiar and comforting to hold onto?

Chapter 14: Only Time

Before anyone in the tavern falls asleep, the order arrives to advance to Ostrovna. They move off towards battle. Rostov notices Ilyin’s agitation about the impending danger, reminding him of his first experiences of battle. They await in reserve until a cavalry charge moves downhill. Nikolai is exhilarated by the sound of gunfire but notices the cavalry are being pursued by French dragoons.

What are the unspoken risks attached to how Nikolai manages ‘his thoughts when in danger’?

Why do you think Tolstoy contrasts the war scenes with descriptions of nature?

As soon as the sun appeared in a clear strip of sky beneath the clouds, the wind fell, as if it dared not spoil the beauty of the summer morning after the storm; drops continued to fall, but vertically now, and all was still. The whole sun appeared on the horizon and disappeared behind a long, narrow cloud that hung above it. A few minutes later it reappeared brighter still from behind the top of the cloud, tearing its edge. Everything grew bright and glittered. And with that light, and as if in reply to it, came the sound of guns ahead of them.

Chapter 15: Moral Nausea

Without reflecting or considering, Nikolai sees that the dragoons can be driven off by the hussars. He leads an attack and overtakes a French officer, striking him with his sabre. The man surrenders, but his homelike face and look of terror haunt Nikolai. Rostov is given the St George’s Cross for bravery but is overwhelmed by moral nausea and incomprehension. Afterwards, he takes command of a hussar battalion.

What is heroism?

Is Nikolai Rostov a hero?

When incomprehension is understanding

Nikolai Rostov’s feelings recall his first experience of battle: At Schöngrabern, he couldn’t conceive why anyone would want to kill him. Here, he cannot make sense of why someone would think he would kill them, even though that is what he was about to do.

Rostov’s instinctive behaviour in this chapter was foreshadowed by Andrei’s thoughts at the council of war: that battles are not decided by strategic genius, but by the ‘man in the ranks’ who shouts hurrah.

But although this makes him a hero in the eyes of others, he is overcome by ‘moral nausea.’ He almost killed a man, struggling with his stirrup, terrified for his life.

‘So that’s all there is in what is called heroism! And did I do it for my country’s sake? And how was he to blame, with his dimple and blue eyes? And how frightened he was! He thought I would kill him. Why should I kill him? My hand trembled. And they have given me a St George’s Cross. I can’t make it out at all.’

Chapter 16: Sympathetic Magic

Natasha has been seriously ill. Her whole family has moved into their house in Moscow, where many expensive doctors are brought in to diagnose and treat the patient. Tolstoy dismisses the efficacy of medicine but recognises its psychological importance to Natasha and her family. In the summer of 1812 the family remain in Moscow, and ‘youth prevails’: Natasha gradually recovers.

Natasha • Sonya • Petya • Count Rostov • Countess Rostova

What is wrong with Natasha?

Do you agree with Tolstoy’s critique of medicine?

Our own peculiar disease

Doctors came to see her singly and in consultation, talking much in French, German, and Latin, blamed one another, and prescribed a great variety of medicines for all the diseases known to them, but the simple idea never occured to any of them that they could not know the disease Natasha was suffering from, as no disease suffered by a live man can be known, for every living person has his own peculiarities and always has his own peculiar, personal, novel, complicated disease, unknown to medicine—not a disease of the lungs, liver, skin, heart, nerves, and so on mentioned in medical books, but a disease consisting of one of the innumberable combinations of the maladies of those organs.

I am going to hazard a guess that Tolstoy was a terrible patient. But then again, medical intervention in 1812 was still primitive and often lethal. Remember Denisov’s bloodletting? This chapter demonstrates Tolstoy’s appreciation of illness as complex and consisting of an important psychological dimension. This makes him sympathetic towards the role of doctors even while dismissing their medicine.

Tolstoy explores a bit of medical anthropology: there will always be ‘pseudo-healers, wise women, homoeopaths, and allopaths’ who will help their patients by giving them a narrative structure to their pain, illness and healing. They satisfy ‘that eternal human need for hope of relief, for sympathy, and that something should be done, which is felt by those who are suffering.’ It is the placebo effect, a powerful force within all our lives regardless of our beliefs or faith in medicine.

Chapter 17: Spiritual Healing

Natasha is calmer but no happier. All joy is gone, and she only finds comfort in the companionship of her brother Petya, and with Pierre. But she is convinced Bezukhov only acts out of universal kindness and pity towards her sad state. Natasha accompanies a neighbour to regular mass to prepare for Holy Communion. She is taken by a religious zeal that gives her a sense of a ‘new, clean life, and of happiness.’

Natasha • Pierre • Petya • Countess Rostova

What are the similarities and differences between Natasha and Marya’s religious faith?

The architecture of a broken heart

Something stood sentinel within her and forbade her every joy.

I am always struck by how seriously Tolstoy takes Natasha’s broken heart. It is a description of depression and a process of grief. He doesn’t say this is how silly young women feel. He lets us all be Natasaha and recognise in her what it is like to feel crushing despair and remorse. And because illness distorts reality, we see her fail to understand the roots of Pierre’s kindness.

Finally, she turns to religion, where ‘Natasha experienced a feeling new to her, a sense of the possibility of correcting her faults, the possibility of a new, clean life, and of happiness.’ As with her sickness, Tolstoy does not sneer at the cure. Natasha finds rebirth in religion as Pierre discovers regeneration with the Masons.

We don’t have to believe in the magic to recognise the process and the enduring human desire to transform and start again.

A touch of satire to finish: Natasha finds religion, but the doctor comes in the next day to deliver the bill.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

“We see, but we don't see. And like this, we grow.” Love this, thanks, Simon🥰

Grandiloquently, my new favorite word!