Welcome to week eighteen of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 2 Part 3 Chapters 17 – 23. Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: Lovers of light

'Darkness and gloom,' reiterated Pierre; 'yes, yes, I understand that.' 'I cannot help loving the light, it is not my fault. And I am very happy!'

This week is all about Andrei and Natasha, and what it feels like when someone brings light into your life. It transforms the world around us: making old pleasures seem dull while softening hard edges and illuminating corners we had previously overlooked. In this new light, the past and future take on new aspects. What once seemed impossible now becomes inevitable.

These blinding illuminations of first love are put into stark contrast with the mirthless laughter of Speranksy's party and the precise imitations of respectable revelry at Berg and Vera’s housewarming.

Berg was satisfied and happy. The smile of pleasure never left his face. The party was very successful and quite like other parties he had seen.

War and Peace revolves around the distinction between affectation and authentic feeling. Sure, Berg is happy. And hey, I’m happy for him. But it is nothing compared to what Natasha is feeling:

She was at that height of bliss when one becomes completely kind and good, and does not believe in the possibility of evil, unhappiness, or sorrow.

This enormous sensation has the power to change how the world looks and how we feel about ourselves. Natasha isn’t happy. She is in bliss.

Of course, she is not completely kind and good, and the world is full of unhappiness and sorrow. And this makes me very anxious about what will happen when she comes down from the clouds. Like Nikolai at war, Natasha is heading for a collision with reality.

But I would rather be Natasha than Vera in this story, chasing the light outside rather than arranging dull mirrors around my room. I know I have both of these women inside me: I am often Vera and I am very happy and satisfied about it. But I know how extraordinary life becomes when I am Natasha, flying to the moon.

The counterpoint to all this love is the dark cave of Pierre’s thoughts. In returning to Hélène, he did what he thought was right. He thought happiness would flow from forgiveness. Instead, it has led him down another dead end.

Natasha’s happiness blinds her from the unhappiness of others, but from Pierre’s gloomy cave, he can see her happiness and the change in Andrei. This provokes a feeling that is “both joyful and painful.” He is not overcome by jealousy for their happiness, but neither is he released from his suffering.

It doesn’t take long for Andrei and Natasha to realise that there is a world beyond the warmth of love’s first light. Andrei discovers a feeling that is “not so bright and poetic as the former” but stronger and more serious. At the same moment, Natasha asks herself: “Can it be true that there can be no more playing with life?”

For here is one of life’s riddles. If Berg and Boris have never seen real sunshine, Andrei is the cynic haunted by rainbows. Once you have glimpsed the sun and felt its warmth, you must find new ways to contend with shadows. We cannot live our entire life in verse, but a life in prose is barely a life at all.

Chapter 17: A superabundance of joy

Natasha is having a ball. Everyone wants to dance with her now, and she is happy and loves everybody. Andrei is smitten and predicts she will be married to someone within a month, perhaps even to him. In contrast, Pierre is in a gloomy mood. For the first time, he feels humiliated by Hélène. Natasha wishes to help him, but she cannot understand why anyone can be unhappy tonight.

Andrei • Boris • Natasha • Sonya • Pierre • Count Rostov

Happiness makes us blind. Tolstoy tells us this by omnisciently noting the things Natasha does not see:

She noticed and saw nothing of what occupied everyone else. Not only did she fail to notice that the Emperor talked a long time with the French ambassador, and how particularly gracious he was to a certain lady, or that Prince So-and-so and So-and-so did and said this and that, and that Hélène had great success and was honoured by the special attention of So-and-so, but she did not even see the Emperor, and only noticed that he had gone because the ball became livelier after his departure.

Because when the Tsar goes to bed, that’s when everyone can really party!

What did you not notice today? What feeling got in the way?

Chapter 18: The hollow life

The next day, Andrei goes back to work but has lost all interest in his labours. He dines with Speranksy and finds the joyless laughter tiresome and unpleasant. Andrei reflects on his time in Petersburg and is ashamed of himself. What he did in the country now feels far more valuable than all this useless work.

There was nothing wrong or unseemly in what they said, it was witty, and might have been funny, but it lacked just that something which is the salt of mirth, and they were not even aware that such a thing existed.

Is this the worst party in War and Peace?

I asked our entertainment correspondent to comment, and this was his dispatch:

Tangent: Andrei in love

This chapter is a miniature masterclass in show-don’t-tell. Andrei is falling in love. Something inside him has come alive. But Tolstoy tells us “his mind did not dwell” on the ball, and the next day, he set off to work. Natasha and the dance are not mentioned again, but we can see the mark they have made in Andrei’s apathy and boredom with his committee work:

A very simple thought occured to him: ‘What does it matter to me or to Bitsky what the Emperor was pleased to say at the Council? Can all that make me any happier or better?’

Even a social gathering with Speranky cannot ignite his interest in his work. Quite the opposite: it revolts him. All he can see is the absence of the “salt of mirth.” All he can hear is Speransky’s high-pitched hollow laughter.

Chapter 19: Alien worlds

Andrei visits the Rostov house, where he is welcomed simply and cordially like an “old friend.” It is like arriving on a “strange world” previously unknown to him, and as Natasha sings, he realises he is crying. Later, unable to sleep, he makes “happy plans for the future.” Pierre, he thinks, was right: “We must believe in the possibility of happiness in order to be happy.”

Andrei • Natasha • Count Rostov

Tangent: The terrible contrast

The chief reason was a sudden, vivid sense of the terrible contrast between something infinitely great and illimitable within him, and that limited and material something that he, and even she, was. This contrast weighed on and yet cheered him while she sang.

What Tolstoy is saying here is interesting. Of course, Andrei is crying as the catharsis of Natasha’s voice lifts him from his former grief. But it is more than that: it is the sense that life is both these frail, failing creatures like Andrei and Natasha and these soaring, limitless expansions of feeling. And it seems impossible and almost terrible that the world contains both. I don’t know about you, but this thought has often struck me, and it almost always leaves a lump in my throat.

Have you felt this? When do you feel it most and how would you describe it?

“Music is the shorthand of emotion. Emotions which let themselves be described in words with such difficulty, are directly conveyed to man in music, and in that is its power and significance.”

LEO TOLSTOY

Tangent: Bury their dead

And he said unto another, Follow me. But he said, Lord, suffer me first to go and bury my father. Jesus said unto him, Let the dead bury their dead: but go thou and preach the kingdom of God. (Luke 9v59-60 KJV)

‘Pierre was right when he said we must believe in the possibility of happiness in order to be happy, and now I do believe in it. Let the dead bury their dead, but while there is life we must live and be happy!’

Was Pierre right? And if so, why is Pierre still unhappy?

Chapter 20: Imperfect Symmetry

Newlyweds Berg and Vera plan a dinner party in their new apartment. Hélène considers it beneath her to accept the invite, but Pierre bumbles along, upsetting the careful symmetry of the Bergs’ tidy study. The happy couple are upwardly mobile and want nothing more than to host a party identical to all others, with their social betters as guests.

Yiyun Li in Tolstoy Together:

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Judging by Berg and Vera, a good marriage is a mirror—spouses look at each other as though looking at themselves, and relish the images.

Tangent: “Everything was just as it was everywhere else”

This gentle satire of social conformity is almost a refreshing change from the emotional intensity of Andrei, Natasha and Pierre. Berg and Vera have none of the high ideals or inner turmoil of our three main characters. They are happy and satisfied and just want everything to be like it is everywhere else.

Is there anything wrong with this?

Last week, I discussed the similarities between Boris Drubetskoy and Ivan Ilyich from Tolstoy’s novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Berg’s party also reminds me of that story:

What Ivan Ilyich enjoyed was small dinner parties to which he would invite ladies and gentelemen occupying high positions in society. He would pass the time with them just as such people generally passed the time themselves; likewise, his own drawing-room resembled everybody else’s drawing-rooms.

Berg is more of a caricature than Ivan Ilyich and he is easy to laugh at. What Tolstoy does with his later novella is create a character that could so easily be us. Because it is not unusual to desire to conform and be accepted by those we admire. We seek comfort, we imitate others. These aren’t sins. In fact, it is very human behaviour. But for Ivan Ilyich, it does have rather terrible consequences.

I wrote a multi-media guide for The Death of Ivan Ilyich to accompany the Audrey audiobook. You can read more about it in my post on Instagram:

Chapter 21: Subtle allusions

Pierre notices the effect Andrei and Natasha are having on each other, and feels both pain and joy to see it. Vera decides her party requires “subtle allusions to the tender passions”, so she asks Andrei what he thinks of Natasha. When an embarrassed Andrei has escaped, he tells Pierre they must talk. Berg decides the party is lacking “a dispute about something important and clever”, so he draws together Pierre and the general.

Natasha • Andrei • Vera • Berg • Pierre • Count Rostov • Sonya • Boris

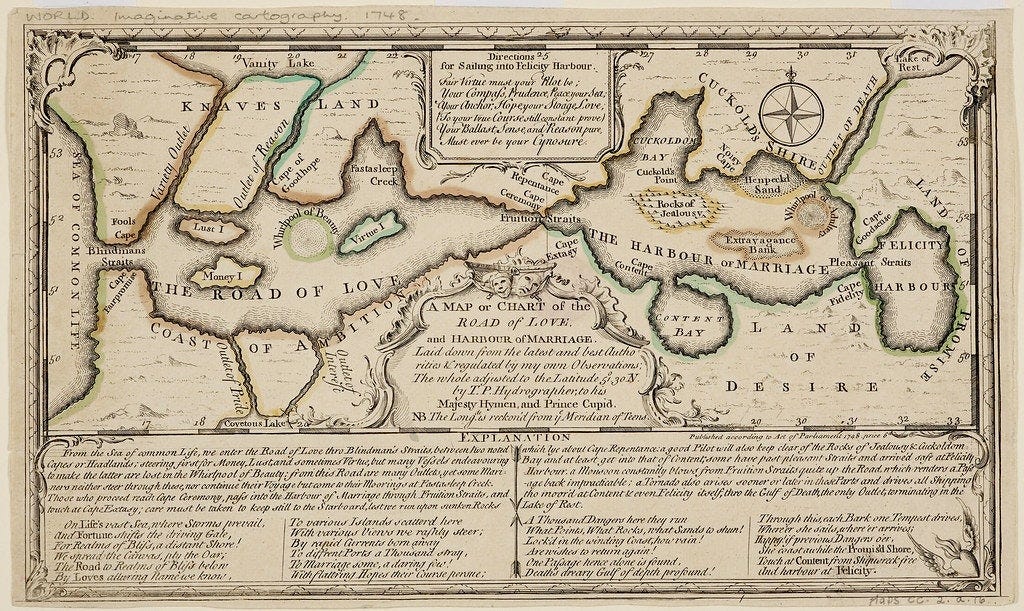

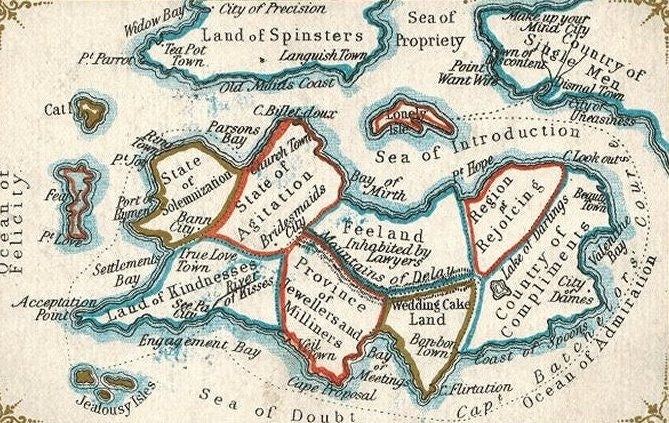

Footnote: Maps of love

As someone who loves a good map and spent a childhood making them, I was delighted to discover this little tangent. Vera alludes to a map of love and you can explore several online. I am now studying these maps to locate our heroes and navigate them out of harm’s way. Is Pierre in the Bay of Cuckoldry? Andrei must have sailed through Blindman’s Strait into the Whirlpool of Beauty. The waters ahead look fraught with dangerous and hidden obstacles.

Chapter 22: Lovers of light

Andrei dines with the Rostovs. Natasha confides in her mother, both frightened about what is happening. Natasha decides it is fate and convinces herself it was love at first sight. Pierre rouses himself from his dark thoughts to tell Andrei to “marry, marry, marry.” He sees a new man in Andrei, a lover of light. Andrei resolves to marry Natasha, with or without his father’s permission.

Andrei • Pierre • Natasha • Sonya • Countess Rostova • Helene

Tangent: distant mirrors

Andrei in Book One:

‘Never, never marry, my dear fellow! That’s my advice: never marry till you can say to yourself that you have done all you are capable of, and until you have ceased to love the woman of your choice and have seen her plainly as she is, or else you will make a cruel and irrevocable mistake.’

Pierre in this chapter:

‘My dear friend, I entreat you, don’t philosophize, don’t doubt, marry, marry, marry … And I am sure there will not be a happier man than you.’

Both friends are offering marital advice from the perspective of their own unhappy marriages.

Why is their advice so different?

Who should Andrei listen to? Himself from Book One, or gloomy Pierre Bezukhov?

Chapter 23: Long shadows

Andrei asks for his father’s consent to his marriage. With “external composure” and “inward wrath” the old man begs Andrei to wait a year and go abroad. Natasha waits in agony for three weeks before Andrei returns. She accepts his proposal and they kiss. Simultaneously, their feelings change, and both become more serious. Natasha thinks a year is “awful” and “impossible” but she accepts it must be so.

Andrei • Natasha • Sonya • Prince Bolkonsky • Countess Rostova • Count Rostov

Tangent: Another little death

Prince Andrei held her hands, looking into her eyes, and did not find in his heart his former love for her. Something in him had suddenly changed; there was no longer the former poetic and mystic charm of desire, but there was pity for her feminine and childish weakness, fear at her devotion and trustfulness, and an oppressive yet joyful sense of the duty that now bound him to her for ever. The present feeling, though not so bright and poetic as the former, was stronger and more serious.

What is going on here? Once again, no sooner has Andrei seen the light, the lofty sky, the gnarly oak, he is plunged once again into darkness. Unlike Vera, he doesn’t have a map to navigate this happiness. So he does what he always does and retreats onto the ground he knows best. Andrew Kaufman1 writes:

Suddenly those lifeless Bolkonskeque abstractions of “duty” and “obligation” take over, killing the flower of authentic emotional connection that was just beginning to emerge. Having projected onto Natasha his own ideals and longing, Andrei can only be disappointed when the reality of her falls short of the image he has created.

Andrei has not escaped his past. He is still chasing after his ideals: glory in war, absolute control of his estates, preservation of his family, the drafting of the perfect law, and now marrying the ideal woman. At each turn, he gets glimpses of another way and the folly of his own approach to life. But he seems unable to abandon his ideals and step back from striving.

Will Andrei ever find a way out?

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

In Give War and Peace A Chance: Tolstoyan Wisdom for Troubled Times, chapter 7. Love.

“We cannot live our entire life in verse, but a life in prose is barely a life at all.” Love this! 😊

Beautiful piece! The delirious joy and aching sadness of Tolstoy’s writing perfectly highlighted. The splinter of ice at the heart of this dissection cuts deep though...

"Berg was satisfied and happy. The smile of pleasure never left his face. The party was very successful and quite like other parties he had seen."

Clinical and humane at the same time. A mirror held up in every depiction.