📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for War and Peace 2024.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 48 of War and Peace 2024

This week, we have read Book 4, Part 4, Chapters 14 – 20

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

Give someone War and Peace in 2025

This readalong will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so more readers can enjoy this slow read of War and Peace. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part next year. Paid subscribers can also join the slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy, read any of my book guides, or participate in the other 2025 slow reads.

This week’s theme: Tell Your Story

‘In general I have noticed that it is very easy to be an interesting man (I am an interesting man now); people invite me out and tell me all about myself.’

War and Peace ends with Pierre and Natasha telling their stories. What happened to them: from the ‘most trifling details’ to the ‘secrets’ of their souls.

I wonder how many people have heard your whole story? It is no small thing: to unburden yourself; to entrust in someone your everything; to make a full confession.

Curiously, not even us readers are given the complete story. There is the thinnest veil between us and the conversation between Marya, Pierre and Natasha. I don’t think we’ve earned their trust, or have a right to their story. It is as though Tolstoy asks us to respect their privacy in these final chapters.

The astonishing thing about War and Peace is how it manages to feel larger than life without abandoning the realism that makes it true to life. Tolstoy does this by drawing our attention to miraculous moments of the everyday. And there are few better examples than Pierre’s potato: the best thing he ever ate.

Marya tells Pierre, ‘they tell such incredible wonders about you.’ They say, for example, that Pierre met Napoleon. The reality is he met Platon, a peasant soldier who gave him a potato. There’s nothing great about meeting Old Bony, but Platon provides Pierre with the most significant moments of his life.

Life is like that. It has all these grand events: births, deaths and marriages. But something will happen to you one morning at breakfast. And you’ll never be able to describe it or put it in a story. But it will be as epic as any Borodino; far greater than Napoleon.

War and Peace began mid-conversation. Anna Pavlovna was chatting to Prince Vasili. She was replying (in French!) to something he had just said, and we were all playing catchup.

And War and Peace ends mid-conversation. Natasha’s speech drifts off into an ellipsis: ‘He must …’

This was never just a novel with a beginning and an end. It was a distillation of life in all its glorious mess. Fade in. Fade out. We leave the lovers here, with a question and an answer, but nothing certain.

Except. Except like us, Tolstoy cannot resist; he cannot stop. So next week, we head seven years into the future, to the first of two epilogues.

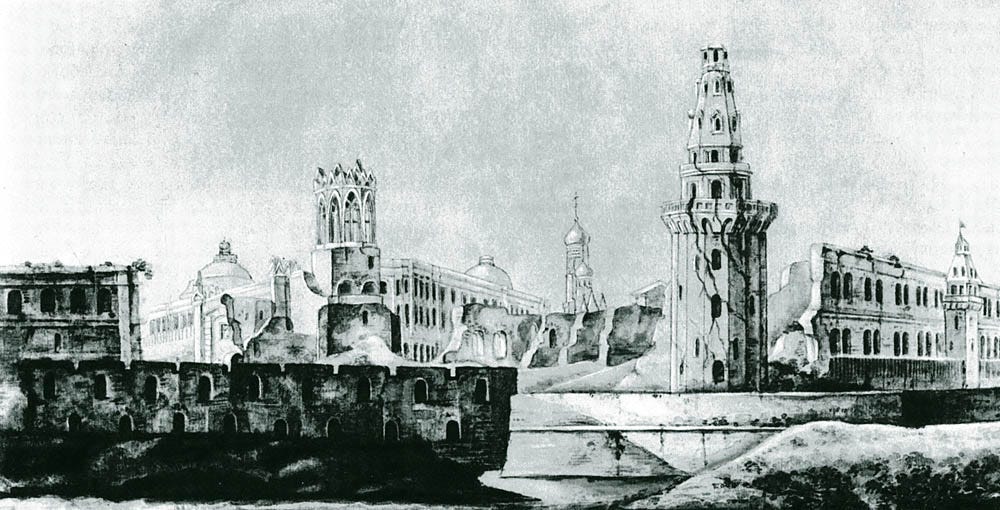

Chapter 14: The Ants Return

The Russians return to Moscow after the French flee the city. The first to arrive plunder the city of everything that remains. But subsequent waves bring commerce and expertise, and within months, the city is thriving once more, its population greater than before the fire. All the while, Count Rastopchin writes proclamations.

All was destroyed, except something intangible yet powerful and indestructible.

Tolstoy writes about the rebirth of Moscow after the fire and occupation. But he could be writing the story of many other communities that have emerged from a disaster, natural or otherwise. An earthquake. A war. A plague. You look at the devastation and wonder how things will ever be the same again.

The rebirth of Moscow mirrors Pierre’s renewal and Natasha’s life force after Andrei’s death. These stories speak to something resilient and resourceful in human nature.

The city returns. It is soon bigger, noisier, and more alive than ever before. And oh yes, of course, there will always be a Count Rastopchin, writing proclamations and pretending he’s in charge.

Can you think of modern examples of this kind of societal rebirth after a disaster? And are there alternative examples where recovery failed?

Further resources:

Footnote: Moscow's Last Great Fire

Tangent: How ant societies point to radical possibilities for humans

Chapter 15: Those We Love

Pierre arrives in Moscow and moves into an outbuilding that survived the fire. He declares his intention to travel to Petersburg. Hearing that Marya Bolkonskaya is in town, he pays a visit. She is in the company of a woman in a black dress. Pierre begins to talk of Andrei and the Rostovs; Marya is embarrassed, for it becomes clear that Pierre has not recognised Natasha. Realising his mistake, he betrays in his manner beyond doubt that he loves her.

When Pierre thinks of Andrei, it is the anguish that his friend may have ‘died in the bitter frame of mind’ he had when Pierre last saw him at Borodino. When he thinks of Platon, he looks past the enormous differences between him and Andrei and sees two men ‘so similar in that they had both lived and both died and in the love he felt for both of them.’

Behind these thoughts are two simple ideas: we wish others a good death; and that the shared experience of life, death and love form a connection between us that overcomes our differences.

Pierre confronts the fact he has lost two men he loved. He then meets Natasha, she smiles, and he blushes: betraying ‘a secret of which he himself had been unaware.’

‘It suffused him, seized him, and enveloped him completely. When she smiled, doubt was no longer possible, it was Natasha and he loved her.’

Oh, Pierre, dear fool. Bless every inch of you.

Exit: The Drubetskoys

On the third day after his arrival he heard from the Drubetskoys that Princess Marya was in Moscow.

We should assume this is Boris and Julie Drubetskoy, and that, unsurprisingly, Boris survived the Battle of Borodino. This is the only reference to Boris in these closing pages of the book. Boring Boris has quite simply written himself out of the story.

In an early draft of War and Peace, there was no Prince Andrei, only Boris. The two men are similar in many ways: bright young men rising fast. But Andrei was tormented by the sense that there was more to life, although he struggled to find it. In contrast, Boris was content to be successful and very very dull.

And now he ceases to be a person. They are ‘the Drubetskoys’. Acquaintances to real characters on real journeys.

Chapter 16: Telling Your Whole Story

Pierre offers his condolences for the death of Natasha’s brother. And then they speak of Andrei and his last days. For the first time, Natasha relates in detail those final weeks and her time spent with Andrei. She rushes from the room, replaced by little Nikolushka. Pierre is tearful but Marya insists he stays for supper.

Pierre • Natasha • Marya • Nikolushka

She spoke, mingling most trifling details with the intimate secrets of her soul, and it seemed as if she could never finish. Several times over she repeated the same thing twice.

How many people in your life know your whole story?

Pierre has discovered the art of listening, if not yet mastered it; Natasha has found her voice. And Marya is the only other soul on earth who can understand this ‘painful and joyous narrative’. As soon as it is over, Natasha must be alone.

Pierre gazed at the door through which she had disappeared, and did not understand why he suddenly felt alone in all the world.

For me, the most profound thing about this scene is that we, the readers, don’t get to hear Natasha’s full story. Of course we don’t; we are eavesdroppers. The experience of death was a mystery disclosed only to Andrei. Natasha walked with him as far as she was permitted to go: her account of that leave-taking is hers to give to the two people who loved Andrei most. And to no one else.

Chapter 17: I Would Do It All Again

Over supper, Marya and Natasha ask Pierre about his current situation. He talks about the guilt he feels concerning his marriage and Hélène’s death. He describes the events of the past few months, reliving them and finding new meaning in his recollections. He tells them he would go through it all again rather than be the person he was before. Natasha understands something from his words that leaves her happy but in tears. Pierre goes home. Afterwards, Marya and Natasha speak of how much Pierre has changed, and of Andrei’s love for him.

‘In general I have noticed that it is very easy to be an interesting man (I am an interesting man now); people invite me out and tell me all about myself.’

Compare Pierre's story of his travails with Nikolai's involuntary boasting of his first experience of combat. Everyone assumes Pierre has done things far more amazing than he really has. In truth, the things he has done are beyond understanding: he saw a man die, and he ate a potato.

Throughout War and Peace, Tolstoy contrasts the head with the heart, thought with feeling, contrived intelligence with natural authenticity, St. Petersburg with Moscow. In these final chapters, Pierre and Natasha converse in a way diametrically opposed to the conversation at Anna Pavlovna’s soirée in the opening chapters. Gone is the clever artificial chit-chat; they give each other their full attention:

Natasha, without knowing it, was all attention: she did not lose a word, no single quiver in Pierre’s voice, no look, no twitch of a muscle in his face, or a single gesture. She caught the unfinished word in its flight and took it straight into her open heart, divining the secret meaning of all Pierre’s mental travail.

Our ‘misfortunes and sufferings’; without them, we would not be who we are today. Pierre and Natasha are transformed, unrecognisable from the start of our story. And they’d do it all again.

Chapter 18: I May Hope

That night, Pierre is unable to sleep. He tells himself he must marry Natasha. The next day, he can think of nothing else and naively assumes everyone else is thinking the same. He continues to visit Natasha but does not propose to her. Alone, Marya gives him hope but tells him to go to Petersburg. For the next two months, Pierre repeats Natasha’s departing words: ‘I shall look forward very much to your return.’

Strange and impossible as such happiness seems, I must do everything that she and I may be man and wife.

Finally, Pierre wants something. Without doubt or hesitation, though it may seem ‘strange and impossible.’ But hope is its own torture, and there is nothing quite so terrible as contemplating the clarity of your feelings against the uncertainty of tomorrow. How much easier it is to be content and want nothing!

In such a state, a few simple words can sustain a romantic heart for many months:

‘What is happening to me? How happy I am!’

Chapter 19: Blissful Insanity

In Petersburg, Pierre is overwhelmed by hope and happiness. His only doubt is that it may all be a dream. He sees everything from a perspective of ‘blissful insanity’. Afterwards, he tells himself he was wisest when he was under the influence of love and immeasurable happiness.

Pierre's insanity consisted in not waiting, as he used to do, to discover personal attributes, which he termed 'good qualities', in people before loving them; his heart was now overflowing with love, and by loving people without cause he discovered indubitable causes for loving them.

Pierre is mad with love. Is our judgement impaired by an excess of happiness? Are we wisest when we think or when we love? Can we even set those two apart?

There is an argument for cool heads, rational thought, and healthy scepticism. But it isn’t one that has much space in War and Peace. Despite its realism, it is a book that appeals to our hopeful, optimistic, romantic nature.

But as Pierre says, that belief in the good comes from life’s strivings, its misfortunes and suffering. He began the novel with a naive, rose-tinted view of the world; he thought too much, and those thoughts had no basis in reality. He ends War and Peace, no less positive in his outlook. But it is borne from experience: yesterday, life was terrible, but I am still here. ‘While there is life there is happiness. There is much, much before us.’

When I first read War and Peace, I was surprised by this ending. I had forgotten how Natasha had looked at Pierre on her name day, when she was only thirteen. Back when she was silly, she loved him for who he was. The whole story seems to be coming back to that moment: two people who love because they know love needs no cause, for by loving people without cause, we discover indubitable causes for loving them.

‘Do you know, that fat Pierre who sat opposite me is so funny!’ said Natasha, stopping suddenly. ‘I feel so happy!’

Chapter 20: This New Feeling

Natasha tells Marya that Pierre looks as if he has come out of a bath. The reunion sparks in Natasha 'a power of life and hope of happiness’. Thinking of her dead brother, Marya grieves this change in Natasha. She tells Natasha what Pierre told her, and Natasha tells her that she loves Pierre.

Twice, Natasha describes Pierre as seeming cleansed, as though from a long bath. These mirror Pierre’s own dream on the eve of his rescue, where he felt himself sink ‘into water so that it closed over his head.’

To her own surprise a power of life and hope of happiness rose to the surface and demanded satisfaction.

The last chapter of War and Peace is given over to the return of Rostov joy: like a duellist undefeated, it demands satisfaction. Like the sky and the stars, Rostov joy is its own character. How dark and dingy this story would have been without its exuberance and excess.

Pierre’s compassion and Natasha’s joy, rearticulated by their journeys, form the two great feelings on which our story ends.

Well, not quite. The epilogue awaits.

Is this a satisfying ending? What do you expect, hope or fear from the epilogue?

And congratulations on finishing the main body of War and Peace. You are awesome! And to prove it, here is a badge from

!On messy endings

In The Guardian, Lee Rourke writes that ‘tidy narrative closure may be entertaining, but loose ends and ambiguity offer a truer sense of real life.’

War and Peace ends where it began: mid-conversation. Part of me thinks the novel could only be improved by lopping off the epilogue and leaving us hanging on Natasha’s words. Will Pierre come back? Will Marya and Nikolai tie the knot?

With Tolstoy, we get a constant battle between the romantic and the realist. He wants to leave us hanging. But he can’t help but tell us a good yarn.

Now that you have finished the main body of War and Peace, I heartily recommend watching Andrew Kaufman’s talk on the book. It pulls together so much of what we have read and may help you reflect on your experience this year:

Thank you for reading

There will be two more posts from me. Next Sunday, I will discuss the first six chapters of the epilogue. And then, you’ll have to wait a little longer for the final post. This will come out on Wednesday, 18 December, when we finish the first part of the epilogue.

I have always argued that readers should treat the second part as an optional appendix. Those who did not enjoy the philosophical chapters in the second part of the book, should take this as permission to shut the book and celebrate having successfully finished War and Peace! No one ever needs to know; your secret is safe with me.

The chat threads will continue up to the end of the book, and I will include some prompts for reflection and discussion of the whole novel. You won’t need to have read the second part of the epilogue to join the chat.

If you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

And that’s all from me this week. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

This is way off point, but today (2 Dec) is the anniversary of the Battle of Austerlitz (book II), where Andrei saw the sky. One of my favorite moments.

I have a huge feeling of satisfaction about reaching this point in the book. I wasn’t necessarily looking for a novel that would top my chart of best-evers; I have been more interested in understanding who Tolstoy was as a writer, what this incredibly famous book is all about and why it has been such a literary centerpiece. And that has happened, and much more(!), through patient reading, the chat, and Simon’s weekly footnotes and tangents. I especially enjoyed the ones this week on Moscow’s burning and new research on ant colonies.

And a note for Simon: I didn’t see the button for your tip jar in this week’s summary, so can you add it? The end of each book is a perfect occasion for adding thank-you bumps to your earnings.