This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 37 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading ‘The Five Wounds, London, Autumn 1536’ This runs from page 279 to 320 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Rumours of Tyndale’s death seep through England’ It ends: ‘God help us for now is the time.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

News of the dead arrives in England from across the narrow sea. William Tyndale may be burned, but reports contradict one another. In France, the Dauphin is poisoned and the English court goes into black. He, Cromwell, knows no other colour.

He goes to Shaftesbury Abbey to see Wolsey’s daughter, Dorothea. He brings gifts, but she rejects them. Against his better judgment, he makes her a proposal. She rejects that, too. She tells him that there is no faith or truth in Cromwell, the man who betrayed her father. Outside, he cries for the first time since Esher.

Rumours circulate. The king is dead, a puppet lies in his bed and wears his crown’, and he, Lord Cromwell, is king. Chapuys talks marriage alliances with Cromwell, and the king considers when to bring Mary back to court. Not yet.

Then, the trouble begins. In Louth, the rebels rise, and the world turns upside down. The king calls his council at Windsor. Henry the Well-Beloved inclines to mercy, but it is his councillors who the rebels want removed. ‘Lord Cromwell’s head is their chief demand.’ The king says he made his minister, and he’ll make Cromwell king if it so pleases him.

The rebellion spreads north. London musters its men and arms. Chapuys crows, and Norfolk paces in his Lambeth armoury. He wants war; he wants to show his loyalty. But the king sends Suffolk instead and orders Norfolk to stay and keep his own country calm. Norfolk spits blood, and Rafe threatens to strike him.

‘That was ill-considered,’ he tells Rafe on the barge. He wants Uncle Norfolk alive and comfortable. ‘He wants him grateful.’ Gregory asks to go fight rebels, but his father sends Richard. They keep their king from the field, full of bombast and bold words. For now, they will negotiate.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Henry VIII • Thomas Wriothesley • Rafe Sadler • Chapuys • Richard Riche • Christophe • Elizabeth Zouche • Dorothea Wolsey • Anthony • Richard Cromwell • Mary Tudor • Thomas Cranmer • William Fitzwilliam • Norfolk • Gregory • Thurston

This week’s theme: His story rewritten

He shakes his head. Dorothea has rewritten his story. She has made him strange to himself. 'Who could have told her I betrayed her father – except her father himself?

This week’s chapter, The Five Wounds, begins with one of the most significant scenes in the entire trilogy: Cromwell’s earth-shaking meeting with Wolsey’s daughter, Dorothea. She believes he has no faith or truth in him. And he arrives at the devastating realisation that his master died believing he had abandoned him. He, ‘our dearly beloved Cromwell.’

The shock almost fells him. ‘He gapes at her. He, Lord Cromwell. He who is never surprised.’ And he cries for the first time since Esher. For what use was his revenge against Wolsey’s enemies, if the cardinal counted him amongst his foe?

You can persuade the quick to think again, but you cannot remake your reputation with the dead.

He kept his promise to Katherine, knowing that ‘the dead do not negotiate’; but he fears he failed the cardinal after all. ‘I should have been with him when he died. I should not have let the king get in my way.’

The thought is vaguely treasonous: it doubles down on the idea of Henry as Cromwell’s nemesis. The king killed Wolsey; the king came between him and his cardinal.

It is a blow far worse than any papist or Yorkshireman can deal him. It makes him ‘strange to himself.’ It adds to the doubt: the growing sense that the past is not what he thought it was.

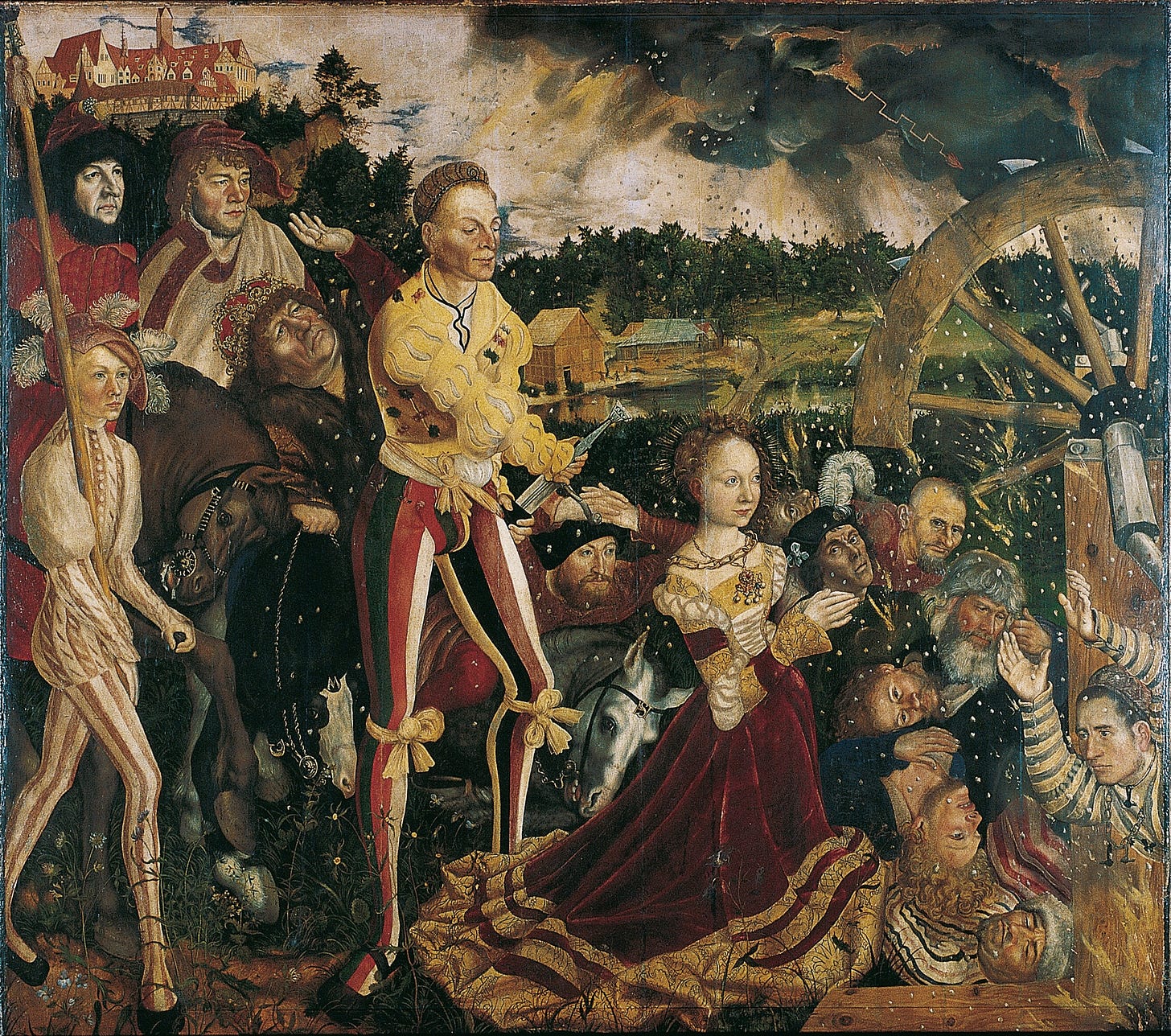

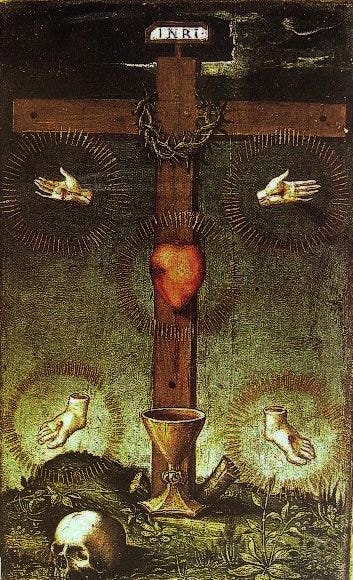

The Pilgrimage of Grace has taken the Five Wounds of Christ as its emblem. They want Cromwell’s head.

Five Wounds. Wife. Children. Master. Dorothea with her needle, straight between his ribs. One withheld? A man might survive them if they were evenly spaced, and he knew the direction from which they would come.

He rewrites his story as four wounds and one withheld. He did not see them coming, for all his powers of memory and foresight. So why, he logically assumes, should he see the next and final wound: the killing blow?

Footnotes

1. Robin Goodfellow

Tyndale knew God’s word and carried a light to guide us through the marsh of interpretation, so we would not be lost – as Tyndale himself put it – like a traveller tricked by Robin Goodfellow, and left stripped and shoeless in the wastes.

According to the OED, the earliest mention of Robin Goodfellow is in Tyndale’s ‘The Obedience of a Christian Man’, published in 1528: ‘The pope is kin to Robin Goodfellow, who sweeps the house, washes the dishes, and purges all by night; but when day comes, there is nothing found clean.’

Mischievous faeries are known as ‘the good folk’ in the hope that flattery will stave off their twilight trickery. Flattery is, of course, the bread and butter of the Tudor court; He, Cromwell, can butter up like the best of them. He is the flatterer-in-chief.

But Robin Goodfellow won’t be sweet-talked. He is a demon or the emissary of Oberon, King of Faery. We will meet him most famously in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream (1595/6), where he also goes by the name of Puck:

I’ll follow you. I’ll lead you about a round, Through a bog, through bush, through brake, through brier. Sometime a horse I’ll be, sometime a hound, A hog, a headless bear, sometime a fire, And neigh, and bark, and grunt, and roar, and burn, Like horse, hound, hog, bear, fire, at every turn.

Robin Goodfellow is a prankster. He tricks people. Remember in Salvage, how they said: ‘Cromwell tricks you, they say. He puts words into your mouth.’ There is something of Robin Goodfellow about Thomas Cromwell, who is now the bogeyman of the Pilgrimage of Grace:

‘Who is Cromwell?’ he asks the messengers. ‘What manner of man do you take him to be?’ Sir, they say, do you not know him? He is the devil in guise of a knave. He wears a hat and under it his horns.

Further reading:

2. Shaftesbury Abbey

Shaftesbury is a town of twelve churches, too many for the inhabitants. When they ring their bells, the streets quake.

Founded in 888 by King Alfred, the Dorest abbey is now the second wealthiest nunnery in England. It seems inconceivable that this institution will be dissolved in 1539, although not inconceivable to Abbess Elizabeth Zouche, who warns Cromwell she will not surrender her house, ‘any year this side of Heaven.’

He had advocated the piecemeal dismantling of the old order, but Thomas Audley and Richard Riche had convinced the king and parliament to make it law: the Act for the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries. ‘No need to frighten the people,’ he had said. Well, now the people are frightened and they are in rebellion. A second act in 1539 will dissolve the rest of the religious houses, including Shaftesbury.

The ground shakes when the bells ring. So when Dorothea reveals that Cardinal Wolsey believed himself betrayed, he, Cromwell, feels the earth give way beneath his feet. It is not the last time in this chapter that the earth beckons him. When Norfolk asks how many men he can muster, he admits to a paltry hundred:

He wishes the ground would open and swallow him.

3. News of the Dead

Anthony walks through Austin Friars, ringing his new silver bells and crying, ‘God be thanked, one Frenchman less!’ The sound fades behind closed doors, up staircases, through distant galleries. ‘One less, who cares how?’ The sound echoes: who-who, an owl's cry: how-how, the hound's call.

Notice the symmetry and the asymmetry. Henry Tudor has just lost his seventeen-year-old son, probably to tuberculosis. Richmond believed himself poisoned by his evil stepmother, Anne Boleyn. The French king’s firstborn, François, has died aged eighteen, also probably from tuberculosis. However, some suspect his younger brother’s wife, Catherine de' Medici, who is now on course to become Queen of France. It will not be the last time she is accused of poisoning her enemies.

But, he asks, why would anyone trouble to poison the boy? François has other sons.

Unlike Henry Tudor, for whom Fitzroy was his only son. And a bastard son at that.

The conflicting reports of the dauphin’s death mirror the rumours of Tyndale’s execution. In October, the English translator had been found guilty of heresy and burned. His death is a response across the water to the killing of his erstwhile opponent, Thomas More, in 1535. Perhaps, we are even now and can call it quits?

Ambassador Chapuys, you notice, has not exactly said he is dead; he has only let him fall, as it were naturally, into the past tense.

In the Cromwell trilogy we live in the present tense. You know you’re done for, when they put you quiet and cold into the dead and lonely past.

4. My familiars and other selves: Christophe and Cranmer

Subtle methods have their place. But any interrogator would look at Christophe and see subtlety as wasted. ‘Christophe,’ he says, ‘if ever –’ He shakes his head. ‘No, never mind.’

It is an unfinished sentence to make the hairs prick up. He means to say, if you Christophe are ever tortured for evidence against him, he wants the Calais boy to squawk, not suffer. The sentence envisions Cromwell’s death. It is not one he wishes to complete, this side of Heaven.

Cranmer says. ‘Crum and Cram and Cramuel. Do you think there is you, my lord, and me, and then some third person compounded of both?’ 'It is a mystery. Like the Trinity.'

Back in Week 7 we were introduced to Dr Chramuel, the composite councillor to Henry VIII. Here he is again. Mantel invites us to consider the two men as mirror selves, the peculiar double act of the English Reformation. In her notes on characters1, she tells Cranmer: ‘When you and your other self are with Henry, you go smoothly into action, able to communicate everything to each other with a glance or a breath.’ Cromwell puts it like this: ‘The archbishop tells Henry how to be good, and I tell him how to be king.’

Both are heretics and could die for it if they are not careful. Chapuys tells him, ‘If Henry were to destroy you for heresy, it would be… It would be a tragedy, Thomas.’ The king, like the cardinal before him, seems to know of the heresy, but elects not to notice it.

The extrovert Cromwell has concealed himself behind a painting (now with many copies, ‘each version is worse,’ he tells Dame Elizabeth Zouche). The introvert Cranmer, on the other hand, has been indiscreet by taking a German wife. It makes him skittish, emitting muffled shrieks, ‘like Jonah’s inside the whale.’

Christophe and Cranmer have nothing in common except Cromwell. They are versions of himself and they have pieces of him. If he were to fall and they were to testify, they know enough between them to bury him deep beneath England’s soil.

5. The Manner of the World Nowadays

It is great pity that every day So many bribers go by the way, And so many extortioners in each country, Saw I never: To thee, Lord, I make my moan, For thou mayst help us every one: Alas, the people is so woe-begone, Worse was it never!

Hilary Mantel has the rebels sing a ballad taken from John Skelton’s poem ‘The Manner of the World Nowadays’. It is worth reading the poem in full. Skelton beseeches the king to do something about the excess of foreigners, pointed shoes and premarital pregnancies, to name just three bugbears from his extensive list. As Cromwell (or Mantel?) notes, the English will always tell you things have never been worse. 1536 or 2024. Worse was it never!

There was a former age, it seems, when wives were chaste and pedlars honest, when roses bloomed at Christmas and every pot bubbled with fat self-renewing capons. If these times are not those times, who is to blame? Londoners, probably.

The chapter concludes with words from John Ball during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Ball also gave us a line we have already heard in Wolf Hall: ‘When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman?’ There were no feudal lords in Eden. This revolutionary idea is alluded to in the conversation between Cromwell, Rafe Sadler and the Duke of Norfolk:

'It is all one, my lord,' Rafe says. 'Blood, I mean. We all come of the same parentage, if you go back far enough.' 'Any priest will tell you,' he says gravely. The duke glares. He knows this is true. But he would prefer if there had been a special Adam and Eve, as forebears to the Howards.

Cromwell is such a compelling character because he embodies all the contradictions of England’s statified society. He delights in annoying snobs like Norfolk, but he fears the anarchy of a true, egalitarian society. He doesn’t mind a social ladder, as long as he’s at the top of it. He’s a religious radical and a social conservative: when men other than him are stirring trouble, he sees base and tawdry motives:

No: these are the complaints of small landowners, and men who don’t like to pay their taxes. Men who want to be petty kings in their shires, who want the women to curtsey as they pass through the marketplace. I know these paltry gods, he thinks. We had them in Putney. They have them everywhere.

6. I am the tree the wind casts down

While the rebels sing ballads penned by John Ball and John Skelton, Cromwell and the king are picking through an Italian songbook. Henry at his lute must make us think of Nero. It was Reginald Pole who called the king Nero and now England burns. The music is a consoling refuge for the king, but for Cromwell, it pins him back to his Italian days: ‘Scaramella goes to war, boot and buckler, lance and shield.’ He hears the drumbeat and maybe feels young again.

Some lines jump out at Cromwell. Here is the English verse in full:

I suffer more and am more wretched Than any living creature upon this earth. I am the tree the wind casts down Because it has no roots, Truly as the saying goes. It goes ill for him upon whom Fortune frowns O my blind and cruel Fate...

How deep are your roots? The question runs through this chapter: ‘At such a time you must feel the inferiority of your birth,’ says Chapuys. ‘Your father was a pauper,’ spits Norfolk. ‘The Howards were merchants once,’ he retorts. And we are all descended from the same father and mother: Adam and Eve. ‘God help us for now is the time,’ says John Ball.

Quote of the week: When this is done

'We have enjoyed the benefits of a forty-year peace,' Wriothesley says, 'under the most sagacious of kings.'

The last revolt on English soil was in 1525. It was put down by Suffolk and Norfolk and it marked the beginning of the end for our cardinal Wolsey. England hasn’t fought a foreign power since the Battle of Flodden against Scotland in 1513. Norfolk’s father was the hero then.

So peace is a forty-year interlude and ‘the time is now’ for a restitution to the old ways:

The web of treason is sticky in the palm, and leaves its bloody smear: the pukers on the Louth cobbles, the fat confederates in the north, the abbots wiping their grease on their napkins and raising a glass of gore: the Scots, the French, Chapuys mon cher, Gardiner plotting in Paris, Pole at his dusty prie-dieu. When this is done, who will be master and who will be man? He pictures Norfolk in his armoury, polishing the plate: diligent he rubs, till he can see his swimming face. The king's companions are prepared to march. So scented, the courtiers, so urbane: the rustle of silk, the soundless tread of padded shoes. But slaughter is their trade. Like butchers in the shambles, it is what they were reared for. Peace, to them, is just the interval between wars. Now the stuff for masques, for interludes, is swept away. It is no more time to dance. The perfumed paw picks up the sword. The lute falls silent. The drum begins to beat.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the first half of ‘Vile Blood, London, Autumn–Winter 1536’ This runs from page 321 to 355 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Aske: he is a petty gentleman…’ It ends: ‘I could smell him from here.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

In the theatre notes for the stage adaptations of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies.

[FOOTNOTE]

It is always worth noting when people act out of character. Cromwell is the master of dissimulation, but he cannot hide his shock and dismay after his interview with Dorothea. He lets Riche see him cry, as he allowed George Cavendish see him at Esher.

He later calls Rafe Sadler 'a more cautious man than he will ever be.' But Sadler, in turn, acts rashly in threatening to strike Uncle Norfolk. It is something Cromwell might like to do, but it is very unwise. Both these scenes tell us a lot about Cromwell and Rafe.

From Bea: "I cannot bear Cromwell’s pain in The Five Wounds. Which is made worse by Dorothea’s rejection of Helen’s “loving stitches”, which will have taken days and days to see."