Augmentation

Wolf Crawl Week 36: Monday 2 September – Sunday 8 September

This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 36 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading ‘Augmentation, London, Autumn 1536’ This runs from page 255 to 277 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘The dead man comes out of the Well with Two Buckets’ It ends: ‘and when they die, they go to Heaven.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

It is Autumn, 1536. Robert Barnes visits him at Austin Friars. Barnes was once an Augustinian friar, brought before the cardinal under suspicion of heresy. He was once a fugitive, a drowned man. Times have changed, and in this new England, Barnes is chaplain to the king, and he, Cromwell, Wolsey’s ruffian heretic, is Lord Privy Seal.

Barnes mediates between England and the German Lutheran princes. Cromwell remembers Wolsey’s foreign policy and his magnificent treaties of peace and pan-European harmony. Barnes is rattled by the mixed messages from England: are we for religious reform, or are we not?

Meanwhile, there is the question of Uncle Norfolk, out of favour with the king. If we ease him back into Henry’s graces, he must know who he owes. This summer, Gregory is sent to hunt with the Howards. And he asks his father when he will have a stepmother.

Gregory is thinking of Katherine Parr, now Lady Latimer, with whom his father flirted so very recently. She had come to ask for a position at court for her sister Anne. But in a quiet moment, she surprised the king’s heretic secretary by asking after William Tyndale, languishing in an Imperial prison.

To Kent with Christophe to see an ageing Henry Wyatt, concerned as always for his wayward son. As he moves, he redistributes land and titles from the dead to the living. The survivors of the summer are augmented. The deceased are forgotten.

Gregory returns from Howard hunting with stories of a surly Surrey and a choleric Duke of Norfolk. The Court of Augmentations is busy turning monks into money, and he, Cromwell, works on Chapuys to augment Norfolk’s purse with imperial coin. ‘You have done me service,’ Norfolk admits. ‘I acknowledge it.’

He summons Hans Holbein to present plans for a whole wall of portraits. ‘The past kings of England.’ Hans wants to paint the living Henry. He, Cromwell, wishes Hans had painted his wife. He tries to picture his daughters’ faces, but he cannot.

It is Autumn, 1536. We were once hunters, but now the days are shortening. And a fat king with a gammy leg stands against a tree and shoots the harts driven to him for a clean kill.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Robert Barnes • Gregory • Richard Cromwell • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Wriothesley • Lady Latimer • Matthew • Christophe • Henry Wyatt • Thomas Seymor • Edward Seymour • Hugh Latimer • Duke of Norfolk • Hans Holbein • Anthony • Chapuys • Henry VIII • Jane Seymour

This week’s theme: The fat of the land

take your father and your housholds, and come unto me, I will give you of the goods in the land of Egypt, so that ye shall eat the fat in the land.

Genesis 45v18, Coverdale translation, 1535.

‘Pig fat is king,’ Christophe says.

This week, Mantel serves us a slim reading and a short chapter, an extended pun on the new Court of Augmentations, the government body set up to oversee the dissolution of the monasteries. The name itself is ironical and unabashed: between this year and 1541, some 900 religious houses were closed down in England. As Cromwell observes, monks were turned into money for the king and his cronies. He had promised to make Henry rich, and this is how he intends to do it.

Augmentation mirrors one of the final chapters of Bring Up the Bodies: Spoils. The living grow fat on the wealth and titles purloined from the dead. Rafe Sadler, Charles Brandon, Henry Courtenay, William Fitzwilliam, the Seymours and Lady Latimer. Cromwell’s pen redraws the map of England, augmenting personal empires and consolidating his own.

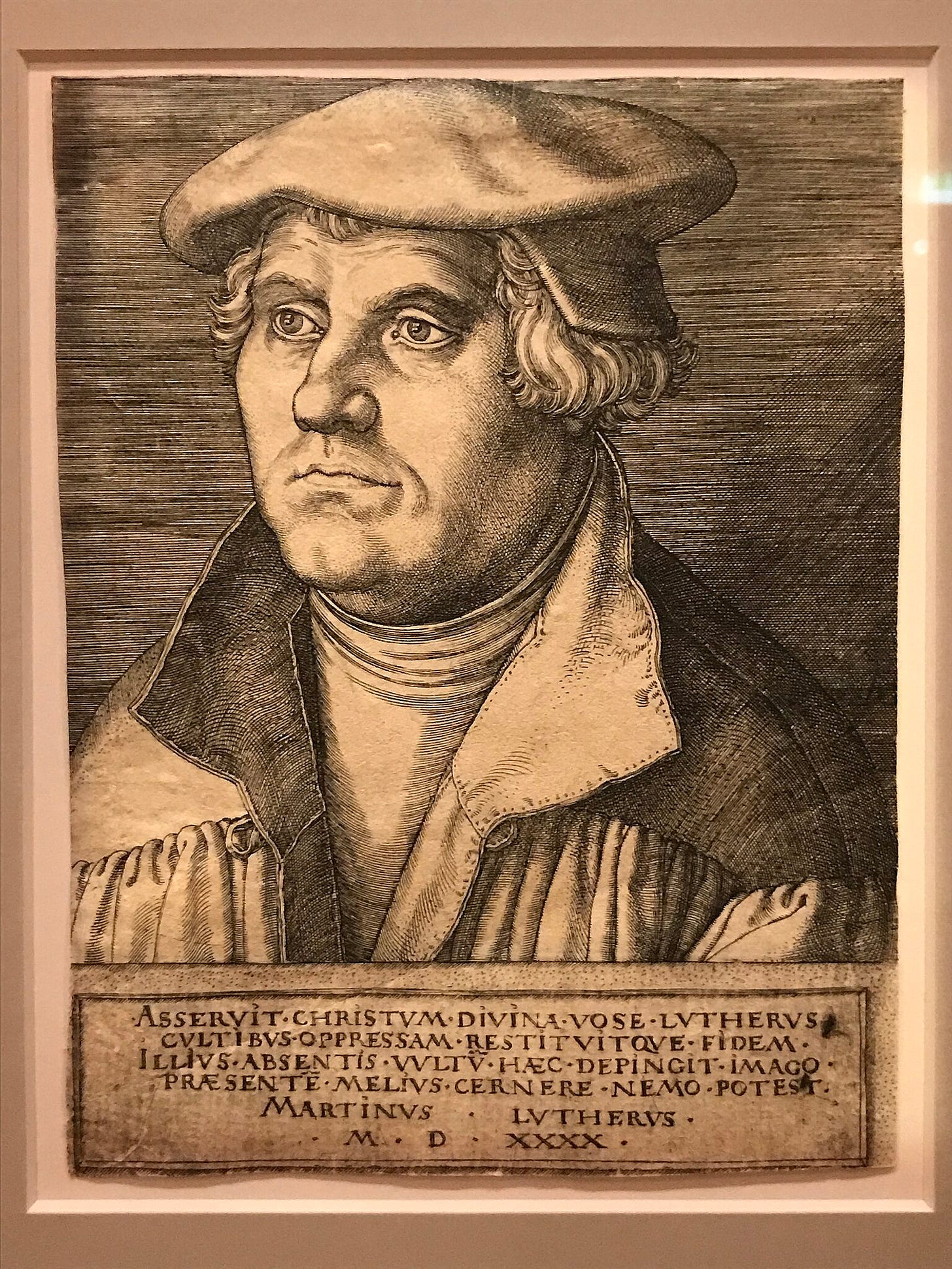

Robert Barnes brings him the latest engravings of ‘Fat Martin’. Luther once looked spiritual, now he is ‘porky.’ The king was once a handsome hunter with a shapely calf. Now, says Hans Holbein, ‘He can no longer ride hard, nor play at tennis.’

'True. The king is augmented.'

Great ships are ‘unloading treasure from Peru’ into the Emperor’s coffers and some of that Inca gold is making its way, indirectly, into the pocket of Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfok. The Venetian ambassador has been granted money for horses. Even Anthony, his jester, is to have bells.

We could call it the Harvest, but we must not be so heartless. Last year, the harvest failed; grain prices were high, and the common folk are still hungry. This chapter is complacent, ignorant of what is to come. Within weeks, the north of England will be in revolt. The greatest rebellion of the Tudor era is coming. And it will start, of course, in Yorkshire.

‘I have been looking over my shoulder for invisible men since Wolsey’s day. I’ve got ears like a fox and my head on a swivel. One sniff of a papist or a Yorkshireman and it swings right round and eyeballs him.’

His antipathy towards the men of Yorkshire was introduced right at the top of Wolf Hall, as he rolled into York Place to see his master, Cardinal Wolsey. ‘So now, tell me how was Yorkshire.’

'Filthy.' He sits down. 'Weather. People. Manners. Morals.'

In the Autumn of 1536, the Pilgrimage of Grace will weld together opponents of the new augmentation. The rebels will direct their ire at its architects: Thomas Cranmer, Richard Riche and Thomas Cromwell. The king had planned to crown Jane Seymour in York, but events will overtake the court. Lady Latimer offers to entertain Cromwell at her Yorkshire home when they come. He says:

‘I beg you to trust no one here at court.’ 'And you, trust no one in Yorkshire.' He breathes in the warm scent of her skin: rose oil, cloves. He looks out of the window. 'I never did.'

Footnotes

1. The Good Doctor Barnes

'Come in, old ghost,' the cardinal's heretic says. 'God's work is marvellous. You bobbing up from your watery grave.'

The first 250 pages of The Mirror and the Light have been haunted by the recently dead: the fear that Anne might put her head back on her shoulders and chase us through Whitehall. Well, here now is a ‘dead man’ who does come back. The good doctor Robert Barnes.

Barnes brings many things to this moment in the story. His arrival provokes a memory: ‘Go back ten years.’ A reminder that the Lord Privy Seal was once just ‘Your man Cromwell’, goading a heretic in the cardinal’s antechamber. But Barnes misread the ruffian. ‘He finds Cromwell incomprehensible.’ Most people do. So he is surprised when Wolsey’s man turns up at Austin Friars with William Tyndale’s Testament.1 ‘I have twenty copies. I can get more.’

Barnes reminds us of this other world where Cromwell was a nobody, but also a time when he was prepared to take risks for his religion. It puts our current position into striking contrast: we are the second man in England, with ‘all to rule’ as Chapuys tells Norfolk. But have we put material gain before spiritual renewal?

'Do you think I am saved?' he says. 'I am covered in lamp black and my hands smell of coin, and when I see myself in a glass I see grime – I suppose that is the beginning of wisdom? About my fallen state, I have no choice but agree. I must meddle with matters that corrupt – it is my office.'

At times, Barnes sounds like his confessor. And, Mantel knows, Crumb has plenty to confess. ‘I sin,’ he tells Barnes. ‘I repent, I lapse, I sin again, I repent and I look to Christ to perfect my imperfection.’

Robert Barnes and Cromwell’s destinies are entwined. They are both up to their necks in a foreign policy set to destroy them. Two days will separate their deaths, one at Tower Hill, the other at Smithfield. Barnes’ death will be the more agonising of the two. ‘Drink up, Dr Barnes,’ said Wolsey. ‘And take the chance. You only get one.’

They have been led through the streets on donkeys, set backwards in the saddle with their faces to the tail. Torn sheets of the writings of Luther are pinned to their coats, and now flap like grey rags. Lashed to their backs, as to his own, are faggots, dry sticks tied up for kindling – it is to remind them the stake is ready, if they offend again. Like Dr Barnes, they have recanted. If they backslide they will die in terror and pain, in public, and their ashes will be thrown on a midden.

2. What he does not believe

Cromwell becomes strident with Barnes, defensive. He is, as Thomas Wyatt warned, in danger of explaining himself:

And I believe, I do believe, that a man who serves the commonweal and does his duty gets a blessing for it, and I do not believe –’ He breaks off, before the magnitude of what he does not believe.

This passage intrigues me. What does he not believe? It remains a curious blank. Hilary Mantel shows us Cromwell wrestling with his conscience, ensnared in self-justification. But we are not brought here to sit in judgment. We watch him as we might watch ourselves: straining to make sense of all our parts. Striving to create a version that is not riddled with contradictions and hypocrisy.

At the start of the chapter, Wolsey told Barnes that he, Lord Chancellor and Cardinal, was church and state. Cromwell is statesman and sinner. He feels strange to himself. He sees he is corrupted but does not know how to be otherwise. It is the nature of things, and the alternative is the fire or the noose.

3. Dun Scotus and Ultima Thule

Barnes leaves him. He looks downcast and is muttering about Dun Scotus. A worldly man, a clever man, but he is afraid to be in England now: as if she were Ultima Thule, where earth, air and water mix to form a jellied broth, and a night lasts six months, and the people dye themselves blue.

Robert Barnes detects theological impurities and inconsistencies in Cromwell’s thought. Barnes is a Lutheran and believes in salvation through faith alone; nothing is possible but by the will of God. Cromwell is less sure: ‘My master Wolsey taught me, try everything. Discard no possibility.’

Barnes goes out grumbling about Dun Scotus, a medieval theologian whose ideas became associated with the Franciscan monks. I’m not sure, but we might hazard that Barnes counts himself as a critic of old Scotus. Opponents called his followers Dunces, which is where we get the ‘dunce cap’ for a dimwitted student. I think Robert Barnes is calling us a theological dunce.

Ultima Thule refers to the most northerly place on the map, a distant isle on the edge of the world. In Olaus Magnus’ 1539 Carta Marina, Thule is situated between Orkney and the Faroe Islands off the Scottish mainland. The term was also used for Iceland and Greenland. Cromwell refers to it as he considers Wolsey’s efforts to turn England into a great nation. This recalls his thoughts in 1530 on the news of his master’s death:

What was England, before Wolsey? A little offshore island, poor and cold.

4. Blessed are the Peacemakers

And so for a year or two it became a question: what does England think? What will England do? France must solicit her: the Emperor must apply.

When I was sixteen, Thomas Wolsey transfixed me. He had me spellbound. ‘He, with his guile and his well-placed bribes, his sorcerer’s wit and his conjurer’s wiles, his skills to make armies and bullion from thin air, to conjure weaponry from mist.’ When I studied him at school, he seemed superhuman, so I was ready to accept the version proffered by Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell.

He made peace look marvellous. We have already mentioned The Field of Cloth of Gold, the extravagant 1520 meeting of monarchs on French soil.

If war is a craft, the cardinal would say, peace is a consumate and blessed art. His peace talks cost as much as most campaigns. His diplomacy was the talk of Constantinople. His treaties were the glory of the west.

As a schoolboy, one summit attracted my attention. In 1518, the major European powers signed the Treaty of London. Masterminded by Wolsey, the non-aggression pact bound all the signatories to eternal peace. Each state agreed to support the others against any aggressor. Of course, the Pope desired this peace to be put to good use by uniting Christendom against the Ottomans. But for Wolsey, it convinced his warlike king that diplomacy could be glorious. And it anticipates by several centuries international bodies like the United Nations and the European Union.

This conjuring trick did not last. By 1521, France and Spain were fighting in Italy. Within a few years, Henry’s desire for a divorce would sour his relations with Katherine’s nephew, Emperor Charles. That, in turn, would destroy Wolsey. Wreckage. And make Thomas Cromwell ‘all to rule’. Salvage. Augmentation.

5. Lady Latimer

'I am glad to see you back at court, my lady. If your sister is as handsome as you, she will do well.'

With wit and guile, Hilary Mantel sneaks Katherine Parr into the story. We haven’t met Henry’s fourth wife yet, Anne of Cleves. But Katherine’s cameo here ensures that we will have met all six of Henry’s wives by the end of Cromwell’s story.

The Parrs were northern gentry. By 1536, Katherine had been married twice, first to Sir Edward Burgh and now to John Neville, Baron Latimer. ‘A papist,’ Cromwell suspects. Latimer’s loyalty will come under intense scrutiny in the coming months as rebellion sweeps England’s northern shires.

'We agreed a husband is no obstacle,' Gregory says. 'Though is not Latimer her second? She does not keep them when they are worn in, I warrant.'

The irony of Gregory’s observation is hidden from him by the future. Katherine will keep the king until he is worn in and in his grave. She will then marry again and for the last time to Tom Seymour, Queen Jane’s rambunctious brother.

‘How do you like Snape Castle?’ 'Well, you know. It's Yorkshire.'

Kate invites Cromwell to dinner at Snape. He will not get the pleasure, nor will he be welcome in those parts in the coming months. In January 1537, Lady Latimer and her stepchildren were held hostage by rebels during the Pilgrimage of Grace. It is rather portentous then that she tells Cromwell, ‘Trust no one in Yorkshire.’

6. Anthony’s Bells

His jester Anthony comes to him: 'Sir, when was it heard of, that a man was fool to the Lord Privy Seal, and was not hung with silver bells?' 'Good idea,' Richard Cromwell says. 'You can ring them to let us know when you make a joke.'

I mentioned this back in Week 21, but it bears repeating. We know Anthony existed because of Thomas Avery’s accounts. On 29 December 1538, Cromwell paid 34 shillings and 6 pence for ‘bells for Anthony’s coat.’ I have to thank Bea Stitches for this detail, and it does make me wonder how much rich detail from Avery’s accounts is woven effortlessly into the narrative:

He says to Anthony, 'Tell Thomas Avery to give you a budget. Then you can buy your own bells.'

Quote of the week: I tell him how to be king

This chapter is about money and morality, power and piety. ‘Blessed are the meek!’ scoffs the Earl of Surrey. Barnes and Cromwell debate whether good works get you into heaven, or whether ‘works follow election’, as Barnes believes: ‘The man who is saved will show it, by his Christian life.’

Somewhat unconvincingly, Cromwell says he has found a compromise:

‘We work it all between us, Cranmer and I. The archbishop tells Henry how to be good, and I tell him how to be king. We do not cut across each other. We try to persuade him that great kings are good kings, and vice versa.’

But he tells his son Gregory to remember the Seven Wise Men. Bias of Priene who said ‘pleistoi anthropoi kakoi, most men are bad.’ Man is wolf to man.

Behind all the chumminess in this chapter, Wolsey’s fireside chats and Cromwell’s munificence, his flirtations with Lady Latimer, his new accord with Thomas Howard. Behind all this outward friendliness, there is the throb of some dark heart, some hidden menace, some bloody end. Which is why the chapter concludes with a description of a deer killed in the hunt. And why, when all is said and done, it is the hunters who live longest and the hunters who will be saved:

If the kill is not clean the hunter tracks the wounded hart, knowing by the quality, colour and thickness of the blood how long the pursuit will last. Hunters, it is said, live longer than other men; they sweat hard and stay lean; when they fall into bed at night they are tired beyond all temptation; and when they die, they go to Heaven.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading ‘The Five Wounds, London, Autumn 1536’ This runs from page 279 to 320 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Rumours of Tyndale’s death seep through England’ It ends: ‘God help us for now is the time.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Barnes's surprise is mirrored a few pages on when Cromwell looks at Katherine Latimer with ‘new eyes’. He thought her a papist, but she asks after Tyndale, now a condemned man.

The little details like the fact about the purchased bells and that we will meet all six of Henry's wives before the end of the book, are what make this read along extra enjoyable.

Lovely. I keep saying this, but how did she do it? Page after page of wit and wisdom and history and action, just beautifully done. I think my favourite this week is the passing reference to “the misunderstanding in Eden”.

(But Dun Scotus, I think, and no need for penises.)