The Great Comet of 1812*

War and Peace Week 24: Book 2, Part 5, Chapter 20 – Book 3, Part 1, Chapter 3

Welcome to week 24 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 2, Part 5, Chapter 20 – Book 3, Part 1, Chapter 3.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. By upgrading to paid or making a one-off donation, you allow me to keep making these posts.

Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: The Great Comet of 1812*

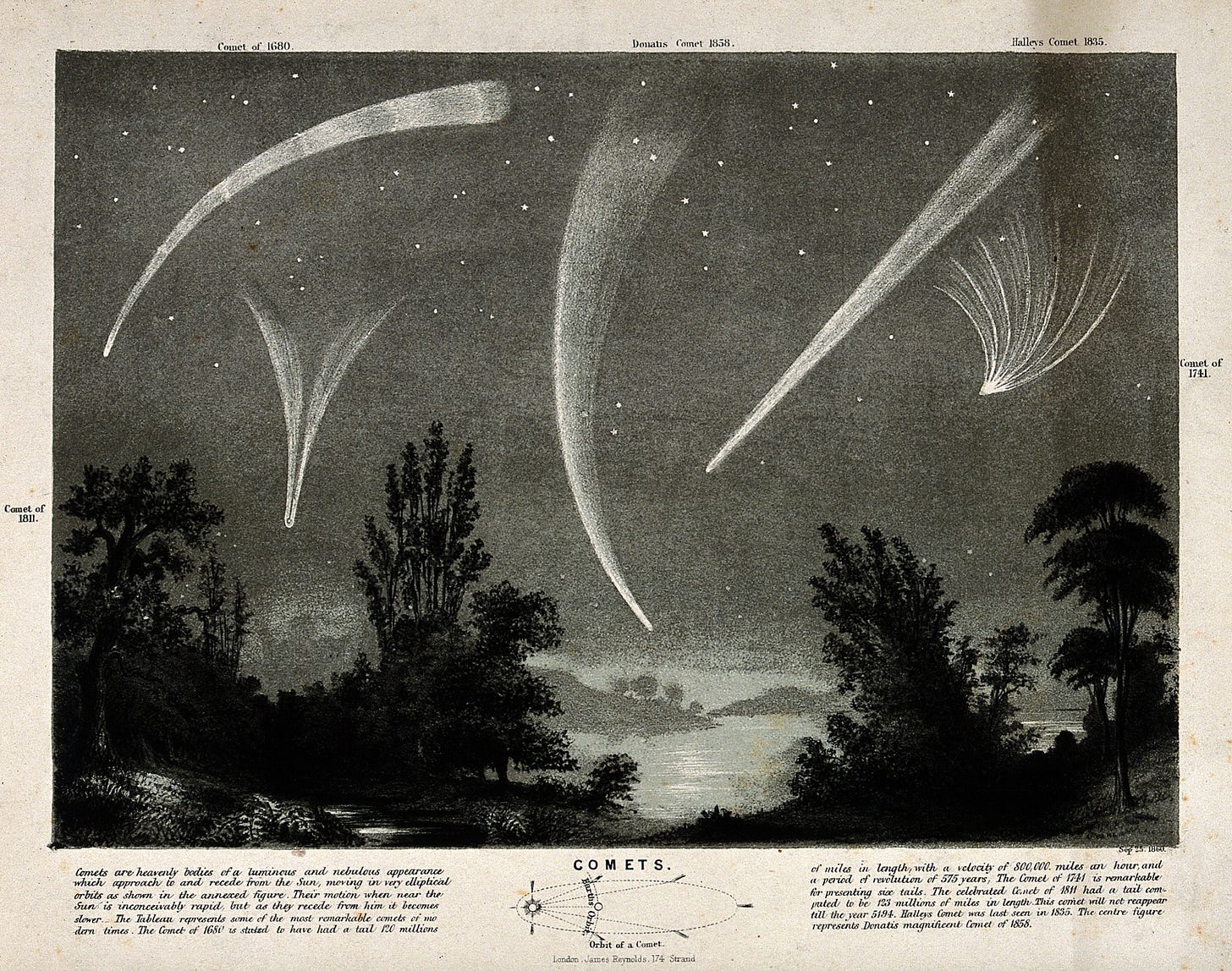

* Or, to give it its real name: The Great Comet of 1811, or C/1811 F1. It was visible from Earth between May 1811 and August 1812, and by that time only with the aid of a telescope. But that won’t stop the famously short-sighted Pierre Bezukhov from spotting it later in September. Needless to say, Tolstoy has taken some poetic licence with this astronomical event.

But we’re going to let him off, because The Great Comet comes in at #5 in my list of favourite minor characters in War and Peace, trailing one-armed pipe-puffing captain Tushin and the Rostov footman Prokofy, who divides his time between plaiting slippers and lifting carriages.

The comet portends the coming war and the end of the world. But for Pierre, it represents a beginning. To slyly quote Thomas Cromwell from our slow read of Wolf Hall: ‘Why are comets bad signs? Why not good signs? Why do they prefigure the fall of nations? Why not their rise?’

‘In Pierre, however, that comet with its long luminous tail aroused no feeling of fear.’

This week, we cross the midpoint of War and Peace, six hundred pages of build-up to the terrible events of 1812. When we ride with Pierre down Prechistenka Boulevard, looking up at the comet, we feel ourselves in the eye of a storm—a moment of supreme stillness and peace, right at the heart of this book.

Tolstoy teaches us to look up, and he reminds us to pay attention. In objective terms, nothing has changed for Pierre. He is no wiser or less foolish than he was this morning. His conversation with Natasha may change his life, or it may not.

All this misses the point: For this sensation of his ‘own softened and uplifted soul, now blossoming into a new life’—this feeling is real. It is as intangible and fleeting as Andrei’s lofty skies above Austerlitz. But where Andrei contemplated his own insignificance, Pierre feels his soul raised above the mundane. Alone in his thoughts, Pierre is at once connected to everything.

Why does he feel this right now? We can talk about this more below. But I think the answer exists in the confessional words shared between him and Natasha. Andrei shuts himself away and says, ‘never speak to me of that’. He cuts himself off; he closes the door.

In contrast, Pierre says what he feels and not what he thinks. He grows confused. He gives Natasha the hope he so badly needs himself. And in giving it, he discovers with joyful astonishment that he has also gained hope for himself.

By forgiving Natasha he forgives himself. By offering hope, he receives it. And by loving Natasha, the world, the comet and the night, he finally finds it possible, at long last, to love himself.

Chapter 20: The Bear and the Snake

Pierre goes in search of Anatole. Rumours of Natasha's abduction have already reached the English Club. Pierre finds Anatole at home with his wife. He loses his temper and orders Anatole to leave Moscow. When Anatole threatens a duel, Pierre swallows his pride and takes back his words. Next day, Anatole leaves the city.

Pierre does good

In the first half of War and Peace, there are very few moments when Pierre actually gets something good done. His conversation with Andrei on the ferry is the most notable example.

So, it is heartening to see Pierre follow The Dragon's request and despatch Anatole from Moscow. And we see a man more in control of his anger than before: he lifts up that paperweight, but 'at once' puts it back. He says the truth, calling Anatole's actions despicable – but he's mature enough now to take back the words to avoid another stupid duel.

How would you apportion responsibility and blame for recent events?

Should Pierre have behaved differently? Would you have done the same?

Chapter 21: Two households, both alike

The night after Natasha learns of Anatole’s marriage, she attempts suicide with arsenic. Pierre visits Andrei when he arrives in Moscow, finding him unnaturally animated about war and politics. Andrei asks his friend to return Natasha’s items and tell her she is ‘perfectly free.’ He adds that he knows she should be forgiven, but he cannot forgive her. Pierre observes the contempt the Bolkonskys have for the Rostovs.

Pierre • Andrei • Prince Bolkonsky • Mademoiselle Bourienne • Marya • Natasha

The head and the heart

Andrei is back! Finally, and far too late. Pierre is the only character who can give us this unique perspective into Andrei’s character: what his animated behaviour really means, stifling thoughts that are too oppressive and too intimate. And the only character who can see clearly the father inside the son: Andrei smiled like his father, ‘coldly, maliciously, and unpleasantly.’ Both men live always in their father’s shadow.

I don’t think the topic of conversation is incidental: Speransky has been thrown out of office. Andrei defends Speransky and scorns those who judge him in his disfavour. ‘I like justice,’ he says. But not, evidently, for Natasha. The mirroring seems to draw attention to the hypocrisy between Andrei’s public and private life. Or, more generously, how difficult it is to reconcile the head with the heart.

The Rostovs are the heart of War and Peace, the Bolkonskys the head. Pierre is strung out between them. He watches sadly as the head and heart part company. As Natasha narrowly avoids a physical death, Andrei once more undergoes a spiritual one. The man who must die again and again.

One chapter away from the midpoint, the head and heart of War and Peace set off to war on different roads. When will they meet again?

Do you have sympathy for Andrei? He is hiding his feelings, so what do you think are his true feelings?

Chapter 22: Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812

Pierre goes to the Rostovs, and Natasha asks to see him. She says she knows it is all over but wants Andrei to forgive her. Pierre’s judgement of Natasha melts away, and feeling sorry for her, he tells her he is her friend, and she has her whole life ahead of her. ‘If I were not myself,’ he says, he would ask for her love. After they part, Pierre rides home under a starry sky and a great comet that portends the end of the world. For Pierre, it is a sign of a new life about to begin.

Natasha • Pierre • Sonya • Marya Dmitrievna

This chapter finishes with one of my favourite passages in the entire book:

It was clear and frosty. Above the dirty ill-lit streets, above the black roofs, stretched the dark starry sky. Only looking up at the sky did Pierre cease to feel how sordid and humiliating were all mundane things compared with the heights to which his soul had just been raised. At the entrance to the Arbat Square an immense expanse of dark starry sky presented itself to his eyes. Almost in the centre of it, above the Prechistenka Boulevard, surrounded and sprinkled on all sides by stars but distinguished from them all by its nearness to the earth, its white light, and its long uplifted tail, shone the enormous and brilliant comet of the year 1812—the comet which was said to portend all kinds of woes and the end of the world. In Pierre, however, that comet with its long luminous tail aroused no feeling of fear. On the contrary he gazed joyfully, his eyes moist with tears, at this bright comet which, having travelled in its orbit with inconceivable velocity through immearsurable space, seemed suddenly—like an arrow piercing the earth—to remain fixed in a chosen spot, vigorously holding its tail erect, shining, and displaying its white light amid countless other scintillating stars. It seemed to Pierre that this comet fully responded to what was passing in his own softened and uplifted soul, now blossoming into a new life.

Andrei saw the ‘lofty skies’ of Austerlitz. Natasha loved the moon of Otradnoe. Pierre witnesses the Great Comet above Moscow. How are these moments different, and what do they have in common?

The comet

The 1811 comet was visible with the naked eye for 260 days, the longest recorded period of visibility until the comet Hale–Bopp appeared in 1997. The comet captured the public imagination. Artists John Linnell and William Blake describe seeing it and Blake may have included it in his panel, The Ghost of a Flea. Besides War and Peace, the comet appears in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and Thomas Hardy’s Two on a Tower.

History’s most famous comet is Halley’s comet, which appears in our skies roughly every 75 years. The last ‘great comet’ was seen in 2020, and astronomers have their telescopes trained on C/2023 A3, a comet that may be visible with the naked eye in late October of this year.

It’s not over yet

We have travelled half a book and half a year with Pierre. We know the world sees him as a ‘fat fool’ and that he agrees with the world. Natasha wants Andrei to forgive her — he has said he can’t. But Pierre needs Natasha’s forgiveness for his own hasty judgement of her in recent chapters.

She says her life is over. He says it has just begun. It is one of the kindest things you can say to anyone (of any age). To give hope is the greatest gift. But rebirth is something Pierre knows a lot about.

‘All over?’ he repeated. ‘If I were not myself, but the handsomest, cleverest, and best man in the world, and were free, I would this moment ask on my knees for your hand and your love.’

As Yiyun Li observes: ‘Pierre seems to be the only man in the novel capable of thinking “If I were not I.” Others—Andrei, old Prince Bolkonksy, Rostov, Anatole—think “It must be so because I am who I am.”’ Pierre’s lack of self-belief is both a weakness and a strength, and wins us over when all other men have been driven astray by their own self-confidence.

But we know from our travels with Pierre that he is not what he and the world think he is. He is more than ‘an absurd fellow’: he is a beautiful human with a sensitive and searching soul. He is worthy of Natasha’s friendship. Worthy of happiness and of peace. And so is Natasha. While there is still breath, it is not over for them.

In the sky, Pierre sees the comet that portends the war of 1812. But for Pierre, it represents hope, peace and rebirth. Which is what this book is all about.

Idealizing versus pitying love

Molly Elizabeth Porter in Tolstoy Together:

Andrei and Pierre both undergo a transformative, sky-blessed love for Natasha, but whereas Andrei falls for her at her literal heights (in the rooms above him at Otradnoe), Pierre falls for her here at her depths. The contrast of idealizing versus pitying love.

Congratulations! You are now halfway through War and Peace. You deserve a badge:

BOOK THREE

PART ONE

Chapter 1: The Coming Catastrophe

Tolstoy starts Book Three by considering the impossibility of understanding the horror of what is about to happen. It is 1812, and war has begun. ‘An event… opposed to human reason and to human nature.’ People will try to explain these events as the cause of one action or one man. But all this fails to grasp the complexity of millions of lives caught up in the course of history.

History is coming for life

In the second half of War and Peace, Tolstoy peppers his story with essays on history. As he writes in the Afterword, War and Peace is ‘not a novel’, although he doesn’t seem entirely clear what it is instead. Which I think makes sense because War and Peace is a reflection of life: and who can say for sure exactly what life is?

Andrew Kaufman writes:

Life, after all, doesn’t often have a perfect beginning, middle, and end, nor clear heroes and villains, nor unifying plotlines. Why, then, should a book? Rather than shoving his world into nice, neat conceptual containers, Tolstoy invited readers to loosen up those containers to fit the very largeness of life.

So, after spending many, many chapters caught up in the turmoil of individual hearts and minds, Tolstoy zooms out. All the way out. We see millions of such hearts and minds, moving inexorably towards a terrible catastrophe: one of the most bloodiest wars Europe had ever seen. How to make sense of such senselessness?

I read this and I am terrified for the Rostovs, the Bolkonskys, and for Pierre. History is coming for them. But I also think about us: living out our ‘swarm-life’ in the 21st Century, feeling free in each moment, but conscious of our own collective future bearing down on us with a frightening inevitability.

How can you relate Tolstoy’s ideas to your life and the world today?

And do you agree with him?

The Causes of the French Invasion of Russia

You may remember that Russia and France have been allies since the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807. So why is France about to invade Russia? Well, Tolstoy dismisses a number of events as ‘labels’ of no real significance. But what are those events?

‘The non-observance of the Continental System’ As part of the alliance, Russia agreed to participate in an economic blockade of the British Empire. However, Russia depended on this trade and by 1811, Alexander had abandoned the blockade.

‘The Duke of Oldenburg’s wrongs’ In 1808, the French occupied Oldenburg in Lower Saxony. The duke fled to Russia, where he married Alexander’s sister Catherine. In 1811, Napoleon annexed Oldenburg, giving Alexander a pretext for war in defence of his brother-in-law.

‘Intoxicating honours in Dresden’ In May, Napoleon gathered together European rulers in Dresden for a lavish series of banquets and concerts. Napoleon reviewed the Grande Armée, now half a million strong. The intended opponent was kept secret, with even some suggestions that France would unite with Russia in a war against the Ottoman Empire.

Chapter 2: The little man in the grey overcoat

Napoleon’s Grande Armée crosses the river Niemen and enters Russian territory. The emperor watches the army advance across three bridges. He orders the Polish Uhlans to find a ford to cross the river. Instead, the colonel leads his men to ‘insane self-oblivion’, swimming the Niemen. Many men and horses drown. Napoleon ignores them but later enrols the colonel in the Legion of Honour.

Marie Louise

Napoleon had explored the idea of marrying Tsar Alexander’s sister, Anna Pavlovna (no—not that Anna Pavlovna). But negotiations broke down, and in 1810, the French emperor married the Austrian emperor’s daughter, Marie Louise. She became Empress of the French and Queen of Italy. In 1812, France and Austria signed an alliance treaty, with the Austrians pledging to support a French invasion of Russia.

Tolstoy wryly notes that Napoleon ‘had left another wife in Paris.’ Napoleon and Joséphine had divorced in 1809 to allow Bonaparte to marry a foreign princess. Napoleon and Joséphine remained friends and some think they continued to be lovers. Of Marie Louise, Napoleon said, ‘It is a womb that I am marrying’. In 1811, she gave birth to Napoleon’s heir, the King of Rome. Napoleon II would very briefly become Emperor of the French after both of Napoleon’s abdications in 1814 and 1815.

What sort of person is Tolstoy’s Napoleon?

Andrei and Pierre both admired Napoleon. What would they think if they saw him at the Niemen?

Chapter 3: Eavesdropping on Emperors

As the French cross the Niemen, the Russians are partying at Vilna. The Tsar has been there a month, and the longer he stays, the less prepared the army has become for action. Hélène is there, with her ‘so-called Russian beauty’. And so is Boris, playing the bachelor and eavesdropping on the emperor for his own career advancement. Hearing that the French have crossed the Niemen, Alexander writes to Napoleon, demanding that he withdraw.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

A particularly good recap this week, Simon! This week we engaged with most of the principal characters and saw portends of the war to come.

These historical chapters make me wonder what it was like for Russians to read this at the time of publication. I’m sure many of them had the events of 1812 burned in their memory, and I can imagine the dread they might feel as certain events draw closer in the narrative.