Welcome to week eleven of War and Peace 2024. This week, we read Book 2, Part 1, Chapters 5 – 11. Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Thank you for your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: The hazards of love

It is so lightly begun.

The first page on the first day of the year. The first glance across a crowded room. A promise to a childhood sweetheart. A challenge to the devil.

One day, you think you're an island and invincible. The next, you've said "Je vous aime" to someone you hardly know. It is so lightly begun.

"Never marry," Andrei told Pierre, a long time ago. And where is Andrei now?

He is dead below his lofty sky, under barrows of the fallen, so quickly forgotten. As the living raise a toast: to lovely women and their lovers. And winter returns to rattle the windows. Where the house is hushed, and the doctor called.

It is so lightly begun. A cell divides and multiplies. Little feet and little heart. Months to carry for hours to come. Snuffling and squealing into the world. This most solemn mystery.

Once begun, it cannot be stopped. Events take their course. And men fire their shots. A look breaks the spell and a snarl cuts the air. The past is severed. The table broken. I hate you. I'll kill you. Get out. And be gone.

What have you done to me? What have I become?

Where is my friend? Coming back from the dead. He hasn't lived and he hasn't loved but now he must and he will. What's lightly begun must be begun again. This time with feeling, this time for real.

This time, my darling, my sweetheart. I'm here. And God is merciful. But what have you done?

Months ago, Marya Dmitrievna told the Rostovs not to fear the coming war. God can be merciful on the battlefield while death strikes at home.

She did not say: the bedchamber is a battlefield. That homecoming heroes will be too late. That they'll break their childish tryst. That they'll profess love and propose marriage. And start the whole bloody thing, all over again.

These are the hazards of love. The blizzards of peace. You think you know yourself. You think you know others. Until you've been tested on the tilting grounds of hope and despair.

And later, an old man and a newborn will sob quietly, before the first larks of spring.

Chapter 5: Folly

Pierre strays into the snow and fires first. He hits Dolokhov in the side. “It’s not over,” says Dolokhov. He takes aim, and Pierre does not cover himself. The shot misses and Dolokhov collapses. A stunned Pierre stumbles into the forest. “Folly!” Rostov and Denisov take Dolokhov away, the wounded man worrying only for his mother. “I have killed her … my adored angel-mother.” He bursts into tears.

Dolokhov • Pierre • Denisov • Nesvitsky • Rostov

Rostov went on ahead to fulfil the request, and to his great surprise learned that Dolokhov the brawler, Dolokhov the bully, lived in Moscow with an old mother and a hunchback sister, and was the most affectionate of sons and brothers.

Tangent: A space for compassion

We had an interesting conversation this week about what to do with this last paragraph in chapter five, where we learn about Dolokhov’s family. Some say this revelation is too on the nose, reminiscent of the gangster who loves his mum. Others argue that this is too little too late to redeem a man who casually destroys lives with no remorse.

I have mentioned before that I don’t think characters are on trial. They don’t exist to entertain us or be judged by us. Like any real person, they need only be understood — although that might be the hardest thing in the world. Fiction offers us a safe space for developing compassion, where we can seek to understand a person more fully. We don’t have to live with them or suffer them, which gives us the opportunity to judge less and listen more.

Here, Tolstoy reminds us that Dolokhov is a real person. He doesn’t just exist to spice up the plot or help Pierre on his road of self-discovery. There are those who love Dolokhov and will mourn his death. And if they love him, I want to know what it is that they know and see in him, that we don’t get to see within the confines of the story of War and Peace. The implication is hard to ignore: all of us deserve to have our story heard. To be treated with compassion, to be understood and to be loved.

What do you think?

Chapter 6: Depravity and self-deception

After the duel, Pierre goes to his father’s room. He broods, and a storm of feelings keeps him awake. He sees that pride and self-deception have undone him and that Hélène is a “depraved woman.” He resolves to leave for Petersburg. The next morning, Hélène calls him a fool for believing the rumours. He threatens her, breaks a marble table, and shouts. She flees the room. He leaves her in control of all his estates and goes to Petersburg.

'Don't speak to me ... I beg you,' muttered Pierre hoarsely. 'Why shouldn't I speak? I can speak as I like, and I tell you plainly that there are not many wives with husbands such as you who would not have taken lovers, but I have not done so,' said she.

Tangent: An autopsy of an unhappy marriage

Early drafts of War and Peace made the incest between Hélène and Anatole more explicit. The 2016 BBC adaptation left no room for doubt. But the final version of the book is masterfully ambiguous about both the incest and her affair with Dolokhov. She denies it; we never see it. All we have are Pierre’s suspicions, Dolokhov’s boasting and the Moscow rumour mill. Absence is everything in this novel, and unless Tolstoy shows us something, we should be ruthlessly sceptical.

Hélène says Dolokhov is “a man who’s a better man than you in every way.” Pierre is a dull, clumsy oaf, and Dolokhov is a brave and decisive soldier, although there are certainly other ways to describe him. If they’re not sleeping together, I’m curious to know what they are doing. If you take Hélène at her word (and I’m not saying you should), there is a fascinating secret subplot in these chapters concerning the friendship of a misunderstood rake and an underestimated society beauty.

As for Pierre, he blames himself. His “inner voice” is very clear on this point. As any of my fellow perfectionists and self-critical idealists will tell you, the fury and frustrations we feel about our own failings far outstrip any animosity toward others. Yes, Pierre hates to be made a fool. Yes, Pierre is jealous. But the “weight on his chest” that explodes into a “delight of frenzy” has very little to do with Hélène and everything to do with Pierre Bezukhov.

Which is, of course, no kind of solace if your name is Hélène Kuragina.

Is Hélène telling the truth?

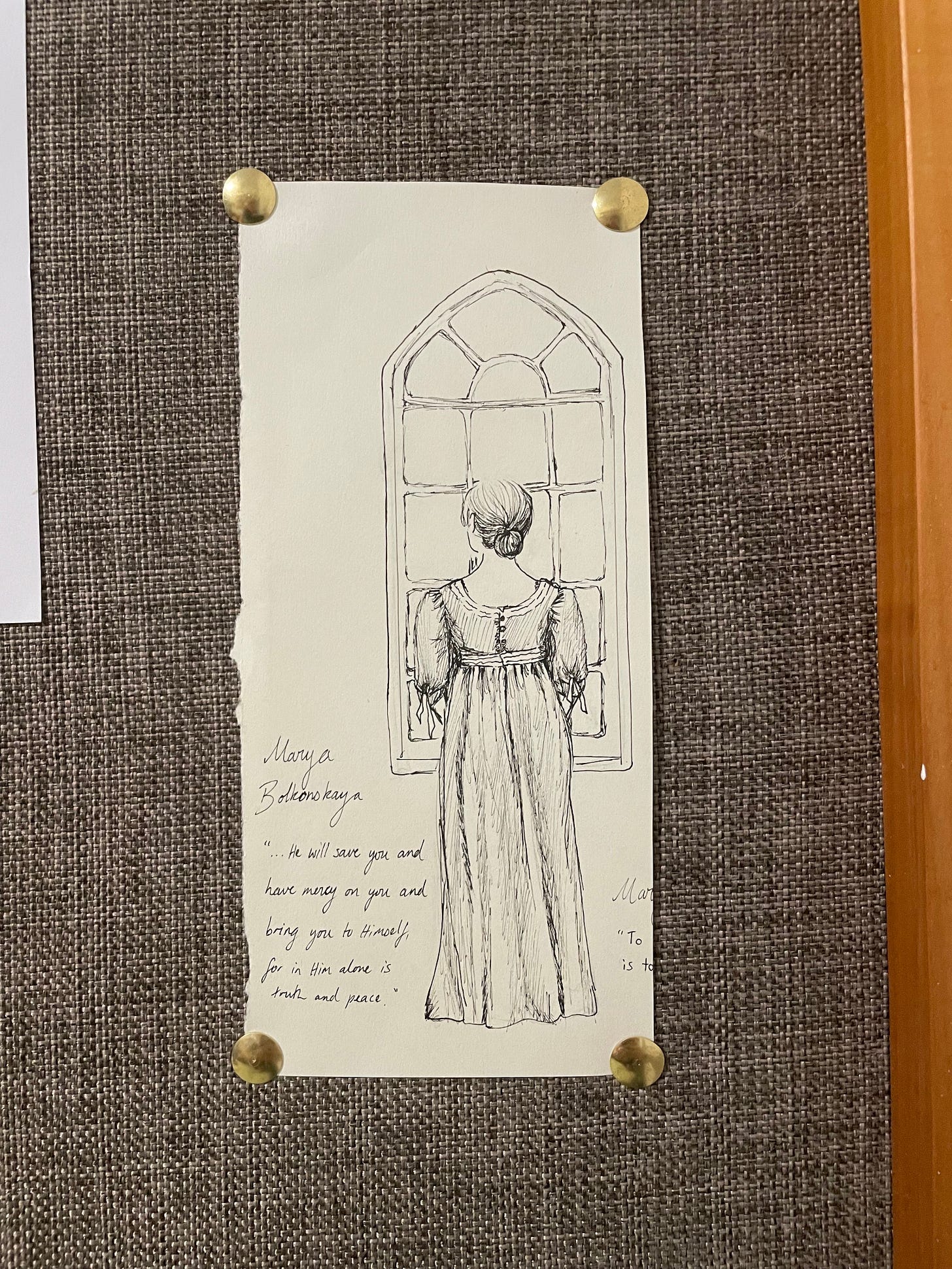

Keep sharing your War and Peace art with me. Above, we have

’s sketch of Marya at a window. And here’s a war-weary Nikolai from :And from

a Count Rostov dancing the Daniel Cooper to cheer us up after a tough few days:Chapter 7: Hope and despair

Kutuzov sends a letter to Prince Bolkonsky telling him what he saw at Austerlitz and saying there is still hope that Andrei is alive. But hope is too dangerous for the old Prince, who retreats into anger and the cold certainty of despair. He orders a monument to Andrei’s memory. In contrast, Marya clings to hope as she does to faith. She decides not to tell Liza until after the birth of the child.

The old prince • Liza • Marya

Prince Marya and the old prince each bore and hid their grief in their own way. The old prince would not cherish any hope… Princess Marya hoped. She prayed for her brother as living, and daily awaited news of his return.

Tangent: What is hope?

April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain.

— The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot

It is March, both in the book and in the world. In the northern hemisphere, we hope for Spring. Each day of icy rain is a kick in the teeth, each shaft of sunlight the fulfilment of our long winter vigil. But at least we know, sooner or later, the frosts will give way, and the warm earth will return to life.

In this chapter, are you Marya or the old prince? Would you hope or despair?

I know how much I hate uncertainty. How the small possibility of hope can eat away at me. I expect I would be Nikolai Bolkonsky, ordering the monument and refusing to read the word “hope” in Kutuzov’s letter.

Tolstoy observes not only how each of us grieves and handles hope differently. But also how those opposite responses drive us apart. Hope is a hot emotion; a volatile substance. When Marya sees her grieving father, she feels the strange joy that comes from shared suffering. Surely here is a bridge between the two of them: —

The princess did not fall down or faint. She was already pale, but on hearing these words her face changed and something brightened in her beautiful radiant eyes. It was as if joy—a supreme joy apart from the joys and sorrows of this world—overflowed the great grief within her. She forgot all fear of her father, went up to him, took his hand, and drawing him down put her arm round his thin scraggy neck.

But no. Hope stands between them. An essential article of faith for Marya. A poison for her father, who is unable to live in limbo, waiting for his son. “He walked less, ate less, slept less, and became weaker every day.”

Chapter 8: The most solemn mystery

One day in March, Liza Bolkonskaya goes into labour. Marya sends for the midwife, and the Moscow doctor. The house falls silent. No one sleeps. The wind rattles the windows, and a gust blows out a candle. Finally, the doctor arrives, with a pale, thin hero back from the dead. Andrei Bolkonsky. “What a strange fate, Masha darling!”

Marya • Prince Bolkonsky • Liza • Andrei

After a while [Tikhon] re-entered [the room] as if to snuff the candles, and seeing that the prince was lying on the sofa, looked at him, noticed his perturbed face, shook his head, and going up to him, silently kissed him on the shoulder and left the room without snuffing the candles or saying why he had entered. The most solemn mystery in the world continued its course. Evening passed, night came, and the feeling of suspense and softening of heart in the presence of the unfathomable did not lessen but increased. No one slept.

From Yiyun Li’s Tolstoy Together:

Not everyone deserves a Tikhon in their lives; every Tikhon deserves a Tolstoy. — Yiyun Li.

Birth unnerves the characters but not the author. Silence reigns, and superstition. Three times Tolstoy evokes the “presence of the unfathomable” —he too has sat silent in those halls, awaiting a child. — Alix Christie

Tolstoy on childbirth—such a simple, elegant sentence in a loud, tragic set of chapters, but it’s what lingered with me most today: “The most solemn mystery in the world continued its course.”

Tangent: A romantic realist

Why is War and Peace my favourite novel? My choice for a desert island? It’s not only about its breadth of human experience. It also contains within it many different types of novel: multiple styles and genres. You get a bit of everything in War and Peace, and today, we are treated to gothic romance, complete with rattling windows and a gust of wind ominously blowing out the candle.

There is a discussion to be had about the accuracy of Tolstoy’s depiction of childbirth. You can find plenty of viewpoints in our chat thread. But I just want to draw attention to the emotional truth of this chapter. Even the most cold-hearted realist must be a romantic when new life comes into the world. I don’t think I understood this until I saw my son and my daughter take their first breaths. I think we’re fooling ourselves if we think we can fully fathom that moment when a new life begins.

Chapter 9: What have you done to me?

Andrei goes in to see Liza. She says nothing. “His coming had nothing to do with her sufferings or with their relief.” Soon after, their son is born, and Liza dies. Both Bolkonsky men read the reproach in her face: What have you done to me? Andrei feels “guilty of a sin he could neither remedy nor forget.” Liza is buried, and five days later, their son Nikolai is baptised.

Andrei • Liza • Prince Bolkonsky

Prince Andrei got up, went to the door, and tried to open it. Someone was holding it shut.

Tangent: We never knew her

The Bolkonskys failed Liza, but I don’t think Tolstoy did. She lit up in company but was starved of it at Bald Hills. When we met her at Anna Pavlovna’s party, we saw her gift for making joy:

Old men and dull, dispirited young ones who looked at her, after being in her company and talking to her a little while, felt as if they too were becoming, like her, full of life and health. All who talked to her, and at each word saw her bright smile and the constant gleam of her white teeth, thought that they were in a specially amiable mood that day.

Hopefully, we all know someone like that. But we never really got to know Liza. The Bolkonksys didn’t understand and couldn’t connect with her emotional world, which was so different from their own. And Tolstoy lets them get between us and Liza so that she seems to disappear altogether. Pale, frightened and shut away. And when one of the Bolkonksy men finally tries to open the door, he cannot. Someone, or something, is holding it shut. It’s too late.

Her death mask accusation seems to scream not only at them but at society and at us: “What have you done to me?”

Only Marya seemed to understand what she was going through. “We should enter into everyone’s situation,” she told Andrei. “To understand everything is to forgive everything.” If the greatest virtue extolled by War and Peace is to strive to understand others, Tolstoy makes us all complicit in Andrei’s greatest sin: to think we know and to cease to understand:

Prince Andrei felt that something gave way in his soul, and that he was guilty of a sin he could neither remedy nor forget.

Chapter 10: Our present, depraved world

Mrs Dolokhov loves her “pure-souled” Fedya. Nikolai loves him too. But Dolokhov loves very few. In early winter 1806, he spends time with Nikolai at the Rostovs, where everyone likes him except for Natasha. Dolokhov falls in love with Sonya, Nikolai stays away from home, and war again looms on the horizon.

I have an adored, a priceless mother, and two or three friends—you among them, as for the rest I only care about them in so far as they are harmful or useful.

I am not convinced that Nikolai is Dolokhov’s friend. So the question must be, dear Nikolai, are you harmful, or are you useful?

In the autumn of 1806 everybody had again begun talking of the war with Napoleon with even greater warmth than the year before.

Footnote: The War of the Fourth Coalition

This is a reminder that war is never far away. Prussia had remained neutral the previous year, as Napoleon destroyed the Austrian and Russian armies. At a secret meeting that year in Potsdam, Prussia had agreed to support Russia against Napoleon. Now, in 1806, Prussia declares war on France.

It goes badly. In only 19 days, the French destroy the Prussian armies and march into Berlin. Napoleon continues the war into Poland and to the Russian frontier.

Chapter 11: The spirit of love

Nikolai arrives late to his own farewell dinner at the Rostovs. The spirit of love in the house has been interrupted by Sonya’s refusal of Dolokhov’s proposal. Nikolai is flattered by this but implores her to reconsider. She tells Nikolai that she loves him as a brother and wants nothing more.

Sonya • Natasha • Denisov • Nikolai • Dolokhov

Never had love been so much in the air, and never had the amorous atmosphere made itself so strongly felt in the Rostovs’ house as at this holiday time. ‘Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly. It is the one thing we are interested in here,’ said the spirit of the place.

Tangent: The house of spirits

This is beautiful. We all know houses have a character, a spirit, a sense of what they are about. And in this book, two houses have the strongest spirits: Bald Hills and the Rostovs’ Moscow mansion. We have to read between the lines in Bald Hills, but the Rostov house shouts its intentions: Seize the day! Spend, love and be merry.

I know it can’t last, I know all else is not folly. But while I am with the Rostovs, I fall under their spell. I listen to the spirits, and I get ready to dance.

What does the spirit of your house say?

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

This book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and have found it useful, please consider a paid subscription or popping a few pennies in my tip jar on Stripe. Paying subscribers can read bonus reviews of all the parties in War and Peace and start their own threads in the chat area. Thank you for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

So much happened this week, right? My head is spinning. Maybe it's because Bald Hills and the Rostov home are so different it's whiplash to move between them. Heck, they could be War and Peace in and of themselves.

Thank you, everyone, who provides artwork for our readalong. I really love all of it!

Simon, this is wonderful! I especially appreciated what you wrote about having compassion for the characters. Judge less and listen more is always great advice both in reading and life.