The Madding Crowd

War and Peace Week 27: Book 3, Part 1, Chapter 18 – Part 2, Chapter 1

Welcome to week 27 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 3, Part 1, Chapter 18 – Part 2, Chapter 1.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. By upgrading to paid or making a one-off donation, you allow me to keep making these posts.

Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: The Madding Crowd

This week cuts close to the bone. Some say it is a little too prescient of our times with the rise of populism, the press of crowds, the din of debates where nothing is said and no one is heard.

But it starts with something else that is, also, uncomfortably familiar: the childlike and childish belief that the world revolves around you. Stuck in your own head with only your life to live, it can take a leap of imagination to see that the universe doesn’t send us signs and that not everything is about you.

For Natasha, this natural narcissism presents itself as a fear: ‘It always seemed to her that everyone who looked at her was thinking only of what had happened to her.’ For Pierre, it is the hope that he is history’s hero, L’Russe Besuhof, who will defeat Napoleon the Antichrist.

The deep irony is that their self-obsession blinds them from recognising when they are, in fact, at the centre of another person’s world. In the Rostov drawing-room, Natasha and Pierre imperfectly realise this and find themselves ‘dismayed and embarrassed’ and uncertain about what to do next.

Meanwhile, history surges forward regardless, with the maddening impulse of crowds. A prayer from the pulpit to the heart of every man: may our enemies be trampled underfoot. A strange shame and sense that one must be part of it: that one must sign up and join in.

Two Pierres began this week as individuals.

One, little Petya, imagined he could speak privately to a gentleman-in-waiting. The other, Count Bezukhov, thought he could bend the will of his peers towards reform.

But history hasn’t got time for this: it comes crashing down on their little dreams, and in the crush of the crowd, all sense is lost, and stupid things are said and done. Free spirits turned into cogs and springs.

In the crowd, they’ll dissolve and disappear. And they’ll say they did it for the emperor, with his kind voice and his tear-filled eyes. They did it for him.

Now he is the heart of the world. Our god on earth. Because here’s the catch: Try as we might, we cannot imagine a universe without a centre, a life without a core. Someone or something that holds it all together.

Or else: the madding crowd.

All Tolstoy’s Parties

I’m clearly not paying our War and Peace entertainment correspondent enough, because his copy is always late and never up to standard. Should I replace him with AI? Anyway, here’s his latest report from the frontline. Judge for yourself:

Chapter 18: A Summer Prayer

On Sunday 12 July, the Rostovs attend mass. It is a bright, hot day, and Natasha feels watched by passersby. She finds herself judged and judging others and horrified by 'her own vileness.' But she is comforted by her prayers for friends and enemies. A special prayer for Russia and against the French invasion moves her and she prays to God to forgive everyone, and forgive herself, and give all peace and happiness.

What is the impact of Tolstoy reproducing the prayer in so much detail?

What do you think about Natasha’s response?

A prayer for deliverance from enemies

‘Preserve his army, put a bow of brass in the hands of those who have armed themselves in Thy Name, and gird their loins with strength for the fight. Take up the spear and shield and arise to help us; confound and put to shame those who have devised evil against us, may they be before the faces of Thy faithful warriors as dust before the wind, and may Thy mighty Angel confound them and put them to flight.’

While some readers interpret this chapter as a critique of the hypocrisy of religion, I think it is about something far more interesting and universal. Natasha feels the conflict between forgiveness and vengeance, deliverance and punishment.

For Andrei, forgiveness is a ‘woman’s virtue’, and life is simpler without it. He runs away from his own humanity. Natasha feels the strong force of praying for deliverance from the French invasion, while feeling unsettled about praying for their destruction.

We find these imprecatory prayers across many cultures and religions. There are several of them in the Bible, including Psalm 69 and Psalm 109:

Let his days be few; and let another take his office.

Let his children be fatherless, and his wife a widow.

This psalm is sung by a choir in Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge, where one of the characters remarks: ‘Whatever Servant David were thinking about when he made a Psalm that nobody can sing without disgracing himself, I can't fathom.’

Scholars and believers debate the purpose and meaning of these prayers and when it is appropriate to use them. And even if we don’t explicitly pray for bad things to happen to our enemies, what does it mean to pray for God to protect our troops?

Mark Twain explored this in his 1905 story, ‘The War Prayer’, in which a stranger appears in church and completes the congregation’s patriotic prayer to their soldiers, graphically describing the suffering that will result from their victory. He is condemned as a lunatic because no one can see the sense in was he said. You can read that story here.

Chapter 19: A Numbers Game

Pierre is in love, and everything else seems of no importance. Everything except the coming catastrophe and his own role in destiny. Seduced by numerology, he manipulates his name to suggest he will stop Napoleon. But in typical fashion, he decides to do nothing. That Sunday, he takes to the Rostovs the emperor’s appeal to the people and the latest news of Nikolai and Andrei.

Do you have a lucky number or a number that hold a special significance for you?

What is the story behind your own name?

The magic of numbers

I did warn you that War and Peace has a bit of everything. Humans have been reading the future in numbers since antiquity. It’s called numerology or arithmancy, and it crops up everywhere. Pierre is using a system first set down by the sixteenth-century polymath Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in his Three Books of Occult Philosophy.

There is actually a contemporary treatise on this subject, published in 1809 called The Identity of Napoleon and Antichrist completely demonstrated. It might all sound ridiculously farfetched (which, of course, it is), but it is not far removed from modern online conspiracy theories.

Note that Andrei and Pierre are running in opposite directions. In his ‘low solid vault’ Andrei feels nothing is ‘eternal or mysterious’ and throws himself into the simplicity of war and revenge. Pierre, once again, believes the answer is mysterious and hidden and must be decoded. In fact, the truth lies in plain sight.

But the punchline for Pierre is the last sentence: having calculated the enormity of his role in history, he elects to wait and do nothing and let fate take its course. How very like Pierre.

Chapter 20: Petya, Petya

Pierre at the Rostovs. Natasha is singing again and wants to know whether Pierre approves. Petya plans to secretly join the Hussars and wants his namesake’s opinion. He, Pierre, is confused. Sonya reads the emperor’s appeal to the people, and Count Rostov shows off his patriotism. ‘We’ll sacrifice everything,’ he says before his youngest son announces his plan to join the army. Pierre leaves early, resolving not to come to the Rostovs again.

Pierre • Natasha • Sonya • Petya • Countess Rostova • Count Rostov • Shinshin

Why does Pierre decide to stop visiting the Rostovs?

What would you say to Petya in this chapter?

The world in miniature

I think this is one of my favourite chapters. This is ‘show not tell’ with very little explained by Tolstoy. He doesn’t need to because we know all these characters so well by now, even the cynical Shinshin. World historic events meet the private corners of individual hearts: Pierre’s confusion, Natasha’s happiness, Petya’s passion, his father’s folly, and his mother’s anguish.

Little Pyotr Rostov wants to put his father’s words into practice and put his life on the line. Big Pyotr Bezukhov wants to speak his truth. But frightened of his own feelings, he banishes himself from the Rostovs.

Chapter 21: The Madding Crowd

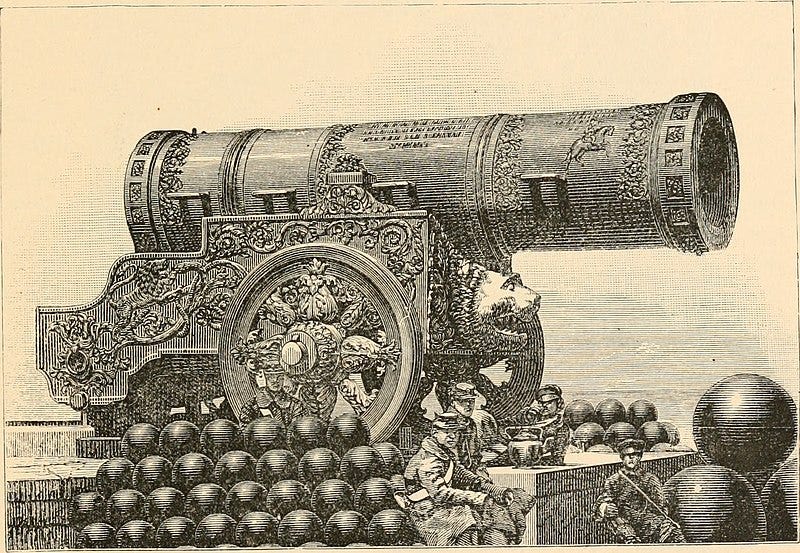

The next day, Petya sets out to see the emperor and to ask to serve his country, despite his youth. Crushed by the crowds, he loses consciousness and is rescued by a church clerk. When the emperor appears outside the church, Petya doesn’t recognise him. Later, the emperor shows himself on the palace balcony and throws biscuits to the crowd. Petya joins a scrum for the biscuits, pushing aside an old woman. The next day, Ilya Rostov enquires whether Petya can serve where there will be the least danger.

Petya • Ilya Rostov • Emperor Alexander

How is Petya like his siblings, Nikolai and Natasha?

When have you experienced the power or the danger of crowds?

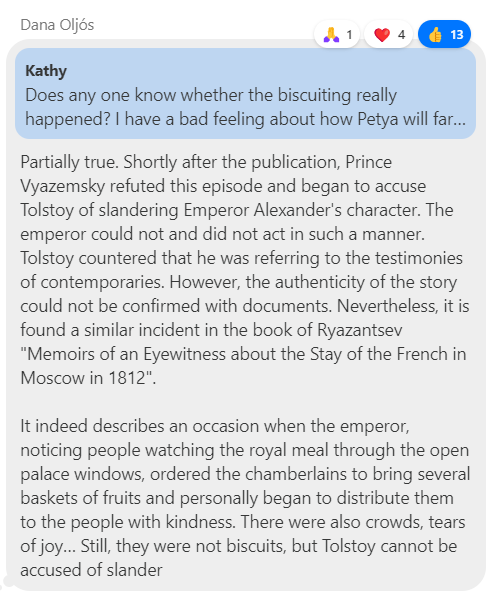

Imperial biscuit crumbs

Many readers were surprised by the depiction of Alexander in this chapter. Until now, he has been portrayed fairly sympathetically. Did this event actually take place? It turns out Tolstoy did face some criticism for this scene.

in our chat filled us in:Distributing baskets of fruit ‘with kindness’ paints a different picture to throwing biscuits. But in another quote, Tolstoy cites Glinka (who appears in the next chapter) as an eyewitness:

The image of the people scrambling for imperial crumbs is a powerful one. It connotes the inequities of power and wealth at the time. But is it true? Is it believable? And does it matter? These are questions for the historical novelists and their readers.

The crush of crowds

Crowds can be terrifying and dangerous places to be. Two of the deadliest crowd crushes in modern history were during the Hajj pilgrimages at Mecca in 1990 and Mina in 2015 – both claiming over a thousand lives.

Closer to our story, at least 1,282 people died at Khodynka Field in Moscow in 1896 at the coronation of Tzar Nicholas II. Leo Tolstoy was so affected by the tragedy he wrote about it in his short story, Khodynka.

Chapter 22: Pierre the Rabble-Rouser

Pierre attends a gathering of nobles and merchants at the Sloboda Palace. Count Bezukhov has renewed thoughts of revolution and reform and tries to insert his ideas into the conversation. But his intervention leads to a shouting match and displays of patriotism, drowning out Pierre’s modest proposal to ask the emperor about the numbers and position of the army.

Is Pierre to blame for the argument?

What is the atmosphere in the room, and how does it change?

What I love about this chapter is the transformation that takes place. At first:

They all preferred listening to speaking.

But by the end, everyone is speaking, and no one is listening:

With an incessant hum of voices the crowd advancecd to the table. Pressed by the throng against the high backs of the chairs, the orators spoke one after another and sometimes two together. Those standing behind noticed what a speaker omitted to say and hastened to supply it. Others in that heat and crush racked their brains to find some thought and hastened to utter it.

Pierre’s radicalism has been slumbering for a long time. But the summoning of the ‘Estates-General’ reminds him of the French king calling a similar assembly in 1789—the event that precipitated the French Revolution. But if Pierre sees himself briefly as a Russian Robespierre, he’s not very successful. This failed intervention has echoes of his disastrous speech to the Freemasons.

Meanwhile, we have poor Count Ilya Rostov, who shares everyone’s opinion but has none of his own. He cuts a comical figure here. But I wonder who is the most dangerous person in the room: the toothless senator or the nodding donkey, Ilya Rostov?

Chapter 23: A Uniform Betrayal

Count Rastopchin ends the row among the nobility and everyone agrees to support the emperor with ten men in every thousand serfs. The emperor thanks them and Pierre feels ashamed of his earlier intervention. He pledges a thousand men, and Count Rostov goes home to consent to Petya’s request to join the army. All remove their uniforms and marvel at what they have done.

Pierre • Count Rostov • Count Rastopchin • Emperor Alexander • Petya

The assembled nobles all took off their uniforms and settled down again in their homes and clubs, and not without some groans gave orders to their stewards about the enrolment, feeling amazed themselves at what they had done.

How sincere are the feelings and actions of Pierre, Alexander and Ilya Rostov?

Why are the assembled nobles amazed by what they have done?

This chapter makes me angry and sad. We end Book One on a real low: two men who are broadly sympathetic characters sign off on an order that will send other men to their deaths.

Until recently, Old Rostov wanted to prevent his son from fighting. Now he goes himself to sign up little Petya. And Pierre wants to unsay his revolutionary sentiments and instead sends a thousand men to die in battle.

For what? All because of a sobbing Emperor and his ‘pleasantly human voice’. The madness of the crowd has worked its deafening magic, and the time for thinking has passed. No wonder, when they have all removed their uniforms, they are amazed at what they have done.

Congratulations on finishing Book 3, Part 1 of War and Peace! Have a badge courtesy of

:Book Three, Part Two

Chapter 1: A Fluke of History

Tolstoy argues that historians have used hindsight to find a clear strategy behind Russian and French actions in the 1812 war. In reality, he writes, events unfolded due to confusion and circumstance, against the wishes of both emperors. The Russians retreated, Smolensk was abandoned and the French advanced towards Moscow and their inevitable destruction.

Napoleon • Alexander • Bagration • Barclay de Tolly

Did you choose to read War and Peace, or did War and Peace choose you? What were the causes and circumstances that brought you to this book?

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

Simon, thanks for sharing that Mark Twain story.

My personal life's reading goal - though ill-defined and disorganized in practice - has been to read "the classics." So War & Peace was always on my mental list. I attempted to read it a while back, but the huge cast of characters in the first couple chapters put me off. So when I stumbled upon your guidance, it was perfect, and perfect timing to set a goal for the year.

The somewhat similar slow read of Dracula (via Dracula Daily), which I did in 2023, also set me up to feel like this was a format I would enjoy.