Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of The Siege of Krishnapur by JG Farrell. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 The Siege of Krishnapur’ in your subscription settings. And for the full experience, read online.

Chapters 18–23

Hope fades in the enclave. Lieutenant Cutter is killed, and a little girl dies of heatstroke. The Collector’s eye becomes swollen, and Hari and the Prime Minister are allowed to go home.

The besieged retreat into the two wheels of the Collector’s inner fortifications, leaving behind a snowstorm of paperwork and a repulsed sepoy attack. Shortly after, the Collector falls ill.

Miriam watches over him, visited by a melancholic Louise. They unite over concern for Fleury and Harry, two men who cannot be relied on to look after their own interests. Lucy, they agree, is a pitiable but unsuitable woman.

Rain finally comes to Krishnapur. The Collector recovers to worries of reputation, green mould and unwanted red hair sprouting from his chin. The cockchafers come; black clouds of flying bugs. They ruin Lucy’s tea party as Harry and Fleury shave her bug body with a bible’s binding. The scene is mythic.

The Collector washes his dirty linen in public, and the dhobi quits the enclave. One baby dies, and another survives. She is christened Hope, for what little there is left.

Footnotes

1. The massacre of hope

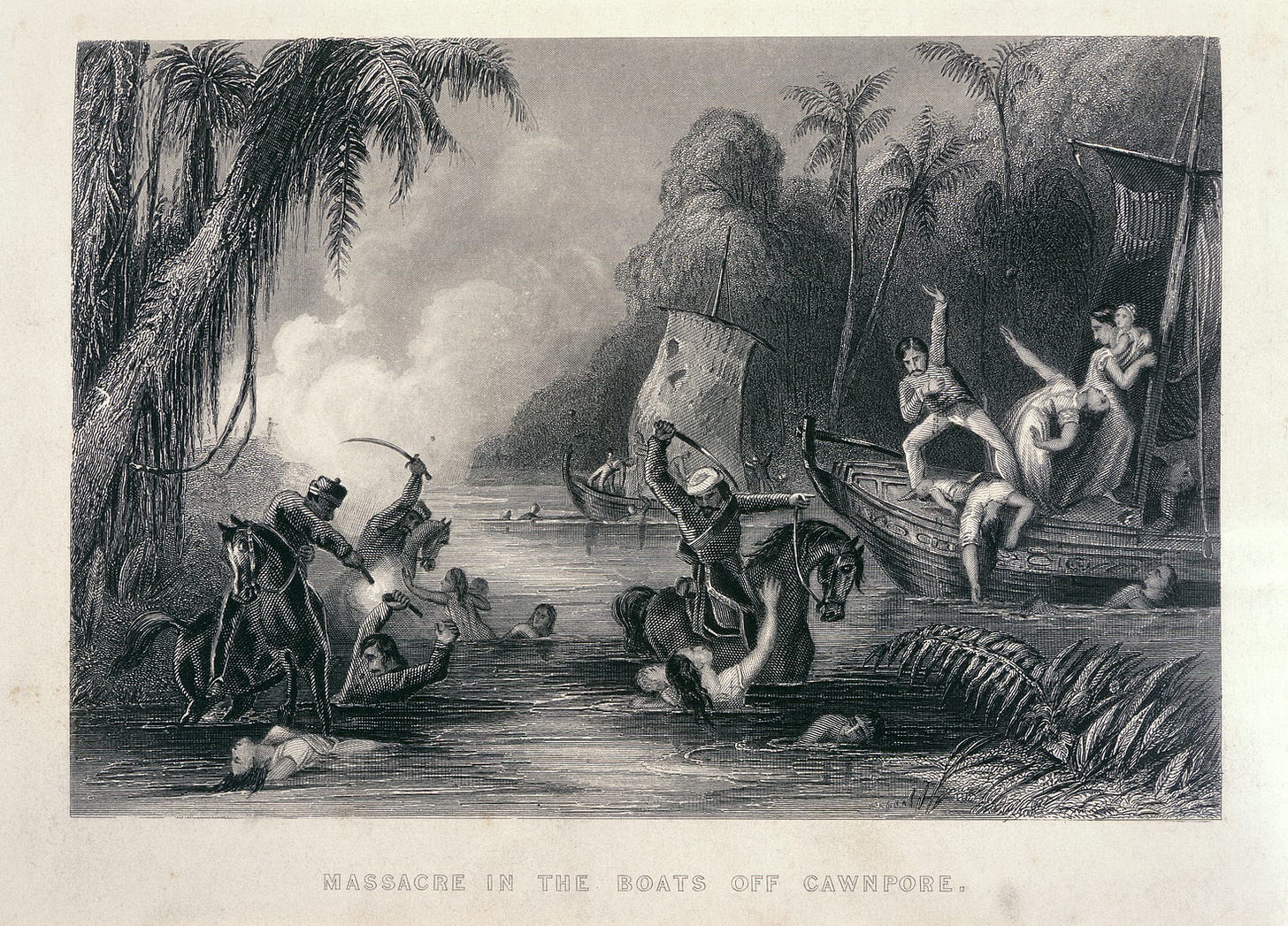

It was said that a massacre had followed the surrender of General Wheeler at Cawnpore and that delicate English girls had been stripped naked and dragged through the streets of Delhi.

News has reached Krishnapur of two massacres that will come to define the ‘Indian mutiny’ in the eyes of the British. On 11 May, the rebels arrived in Delhi to restore the Mughal monarchy under Bahadur Shah II. Sepoys and civilian rioters turned on the British residents, killing all Europeans and Christian Indians who could not escape.

On 27 June, the siege of Cawnpore ended with the British surrender and negotiated safe passage to Allahabad. The men were killed in boats on the Ganges. The women and children were taken hostage and then butchered on 15 July at Bibi Ghar as the Company rescue force approached.

After 35 days of siege, Cormontaigne advises that ‘it is now time to surrender.’ No wonder the Collector feels hope has all but died.

Footnote: Delhi, 1857: a bloody warning to today's imperial occupiers (William Dalrymple)

2. The White Man’s Burden

Looking at the Prime Minister the Collector was overcome by a feeling of helplessness. He realized that there was a whole way of life of the people in India which he would never get to know and which was totally indifferent to him and his concerns.

I find the Collector’s steady disenchantment fascinating, moving and disturbing. He becomes increasingly aware of how little he understands the world. The lack of Indian voices and perspectives in the novel exacerbates this sense of isolation and ignorance. We, as readers, are forced to see the world from the myopic viewpoint of the Collector. He is dimly aware of another India that has no interest in him.

Open revolt and rebellion have punctured through this mutual indifference, creating the strangest of reactions in the Collector’s confused mind:

The Collector’s telescope had wandered, however, to the slope above the melon beds where the densely crowded onlookers were shouting, cheering, and waving banners in a frenzy of excitement. ‘How happy they are!’ thought the Collector, in spite of the pain. ‘It is good that the natives should be happy for surely that is ultimately what we, the Company, are in India to procure …’

Procure is such an interesting word because, of course, the British are in India to procure wealth, not the native’s happiness. But the fiction of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ is that the colonizers are duty bound to bring civilisation to the colonized. The British Empire spreads happiness! And if that happiness is procured by the massacre of the British, well, so be it.

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

— From ‘The White Man's Burden’ by Rudyard Kipling

The civilising mission of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ included the idea of teaching ‘the natives’ personal hygiene. Farrell continues to draw parallels between how the British men regard Indians and women. In chapter 23, the Collector flies into a rage and berates the billiard room women on how to look after each other.

They had listened meekly, shamed by his anger and, like children, trying to think of ways to please him; but once he had left the billiard room he knew that the feuds would start once more to germinate.

3. Tired of womanhood

Once in her life already she had become attached to someone and had allowed herself to be swept down with him in his lonely vortex into the silent depths where nothing moves but drowned sailors coughing sea-weed; only Miriam herself knew how much it had cost her to ascend against that fascinating, ghostly world towards light and life.

Miriam interests me. We see how her brother engages clumsily with the idea of what it means to a Victorian man. She, too, is uncomfortable with the strictures and expectations imposed upon her. Her brother was wrong about her and the Collector: she ‘had taken great pains’ to avoid those feelings that would condemn her to ‘womanhood.’

Miriam was tired of womanhood. She wanted simply to experience life as an anonymous human being of flesh and blood. She was tired of having to adjust to other people’s ideas of what a woman should be.

4. Greenwood fantasy

Love, pride, and foolishness combined to make him keep on wearing the green coat, however.

How symbolic this coat has become! How the English revere their Robin Hood, their rebel hero. We cannot fail to cheer him on, though he is a bandit and an enemy of the law. His suit is camouflage in Sherwood Forest, but out here in this dusty besieged enclave, he is a sitting duck. And he is not the rebel, but the rebel’s bullseye.

The Englishman always wants to be Robin Hood, but he is condemned to play the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Footnote: Victorian Legacies: Robin Hood: A Romantic Hero (Romantic Textualities)

5. The noble savage

‘And everywhere he is in chains!’ crised the Collector urgently in his delirium, causing both young laties to turn anxiously towards his bed.’

The Collector is completing the opening line of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract: ‘Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.’ Rousseau expounded the idea of the ‘noble savage’ and that civilisation corrupts human nature. This is not a notion that sits comfortably in the Collector’s mind.

6. The fleeting years

‘Eheu fugaces!’ she thought and almost said, but was not quite sure how pronounce it.

Louise is quoting the Roman poet Horace, ‘eheu fugaces labuntur anni’. Alas! The fleeting years slip by. For all her supposed vapidity, Louise is practical and learned, and not at all the woman George Fleury thinks she is.

7. The Plagues of Egypt?

The heat, which had declined a little at the coming of the rains, grew more oppressive than ever. At night a clamour of frogs and crickets arose and this diabolical piping served to string the nerves which were already humming tight a little tigher.

Farrell is a master at combining horror and humour. The descent of thousands of flying bugs onto Lucy’s body is gruesome, with a real Hitchcockian horror to it. Fleury and Harry’s consternation over her pubic hair is hilarious:

It was not something that had ever occurred to them as possible, likely, or even, desirable. 'D'you think this is supposed to be here?' asked Harry, who had spent a moment or two scraping at it ineffectually with his board.

They are using the cover boards of Fleury’s Bible as ‘giant razor blades’. And this made me wonder whether Farrell is alluding throughout these pages to the ten plagues of Egypt.

Those plagues mirror many of the afflictions of Krishnapur: boils, lice, pestilence, thunderstorms, wild animals (the pariah dogs?) and swarms of insects. The final plague is the death of every firstborn. In Krishnapur, two children die (those of Mrs Scott and Mrs Bennett), and one survives – optimistically christened ‘Hope.’

How haggard and bereft of hope they looked!

8. Moving pictures

This coming and going of black and white was just fast enoughh to give a faint, flickering image of Lucy’s delightful nakedness and all of a sudden gave Fleury an idea. Could one have a series of daguerrotypes which would give the impression of movement? ‘I must invent the “moving daguerrotype” later on which I have a moment to spare,’ he told himself, but an instant later this important idea had gone out of his mind, for this was an emergency.

The inventor of the catastrophic Fleury Cavalry Eradictaor has stumbled momentarily on the idea of moving pictures. In reality, chronophotography would not be achieved until the 1870s, when Eadweard Muybridge photographed (not eradicated) a horse in motion.

Watch: Slices of Time: Eadweard Muybridge’s Cinematic Legacy (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

9. Andromeda

Her body, both young men were interested to discover, was remarkably like the statues of young women they had seen ... like, for instance, the Collector's plaster cast of Andromeda Exposed to the Monster, though, of course, without any chains.

It is hard to make sense of this nightmarish scene. Andromeda appears in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, rescued by Perseus, an example of the trope of the hero rescuing the princess from the dragon. This is just the sort of romantic fantasy of chivalric daring-do that appeals to Fleury and Harry, who previously failed in saving her from herself and the mutinous sepoys.

Cockchafers are hardly the sea monster, Cetus. This is a tableau of bathos, where the sublime and heroic are reduced to the ridiculous. They may rid Lucy of ‘flying bugs’ only to all succumb to any manner of real threats, from cannon fire to cholera. And besides, Fleury and Harry have failed in the far more elementary quest of providing Lucy with a reason to live.

Not long ago shhe had begun to talk of life not being worth living again and shhe had demanded that Harry should tell her, once and for all, why it was worth living.

It is significant that this episode is linked back to an object in the Collector’s study. Andromeda is a male fantasy, a powerful man rescuing a helpless woman. It mirrors the imagery of the ‘White Man’s Burden’ and the civilising mission of colonialism. Both are satirised by events within the enclave.

Footnote: Andromeda, the Hero (The Victorian Web)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read of JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. Please share your own footnotes and tangents in the comments, and let us know what you thought of this week’s reading.

I will be back next week when we will read Chapters 24–27 of The Siege of Krishnapur.

I thought of the plagues of Egypt too! The allusion must be deliberate, because Farrell makes a point of mentioning lice, boils, and locusts (well, cockchafers) in the same section where the first of two babies born on the same day dies. The plagues make sense thematically, because they were God’s message to Pharaoh to stop committing the evil act of enslaving people—just as the more enlightened English colonizers (Louise and the Collector) are discovering that perhaps the people of India do not appreciate their “civilizing” mission.

Another tangent: Fleury’s and Harry’s consternation at Lucy’s pubic hair might be an allusion to the rumor that Ruskin’s marriage had to be annulled, unconsummated, because he was so disturbed by the sight of his wife’s pubic hair on their wedding night. After a lifetime of looking pure white marble statues of women, Ruskin may not have been equipped to handle a flesh-and-blood woman.

I hope it’s ok to share a link to a piece I wrote that discusses the Ruskin story and also shares a portrait of him, painted by the man who wound up marrying Ruskin’s rejected wife:

https://open.substack.com/pub/marischindele/p/art-i-liked-at-the-ashmolean?r=7fpv6&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Another wonderful reading, Simon, thank you.

I find Kipling to be so fascinating.

His novel Kim is so very complex and compelling. Leave aside what Kipling was for a moment, a staunch imperialist and believer in the idea of empire. I wonder if the novel reveals layers inside him he was not aware of. And the fact that Kim is the son of poor Irish, not English parents is interesting. Kim is a classic insider / outsider, observing India and the great game as both Indian and non Indian. Its a novel that may be the mother of stories of divided identity and the nuances and complexities of that, which can be seen as a theme through novels of modern diasporas too.

The Sherwood mythology is so interesting too. I think England has two great mythologies - Arthur, and Sherwood.

I've had a thought about Robin Hood (sorry for slight tangent) - he's considered a rebel but I think he may be an echo of conservatism and the Restoration. And it feeds into the earlier Arthurian mythology too. The King is absent in the land on the crusade, and a tyrant arises (the Sheriff of Nottingham) in his absence. Robin Hood is the loyal yeoman Englishman who rebels against that tyrant until order can be restored under the righteous rule of King Richard. He rebels against unjust law, but is a loyalist to the law of the just and righteous King who is absent.

The pubic hair reference reminds me of something I read, that John Ruskin was so shocked and horrified on his wedding night to see that his wife had pubic hair, that he refused to consummate his marriage, believing her to be deformed. They idealised women so much in Victorian times, the actual reality could cause a breakdown in some men.

The richness of allusions that you identify really are fascinating. What a multifarious novel, what a brilliant and unique novel