The Image of the King (Part 2/2) / Broken on the Body

Wolf Crawl Week 42: Monday 14 October – Sunday 20 October

📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 42 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the second part of ‘The Image of the King, Spring–Summer 1537’ followed by ‘Broken on the Body, London, Autumn 1537’. This runs from page 478 to 520 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘As July comes in Lord Latimer is down from the north.’ It ends: ‘My lord father, who will you let the king marry next?’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Are you enjoying Wolf Crawl? I need your help!

This month, I will launch the 2025 slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. If you have enjoyed reading with us this year, I would love to hear from you. Your feedback will be enormously helpful for new readers deciding whether to join us in 2025. What were your expectations? What was your experience of reading slowly? What surprised you? And would you recommend this slow read? If you are happy for me to share your thoughts with future readers, please send me an email or a DM on Substack, or leave a comment below. Thank you so much for your time.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

June, 1537. The new Queen of Scots is dead, and in Calais, Lady Lisle’s unborn child has mysteriously failed to be born. These are not good omens.

In the queen’s privy gardens, Lady Oughtred walks out with her would-be husband, Lord Privy Seal, only to discover that there has been a misunderstanding: she is to wed Gregory and be plain Mistress Cromwell.

The Cromwells prepare for the wedding. The rebels are all dead, and so is Harry Percy, Earl of Northumberland. He, Cromwell, asks the king for mercy for one of the Pilgrims to save her from burning. At the Charterhouse, the monks are shut away and dying of the plague; Richard Riche, the good servant to the state, counts their worth and waits.

He goes to court with a greyhound for Lady Mary. There, he runs into the Earl of Surrey. Surrey curses the Cromwell name and spills vile blood – Mathew’s, the boy with many names. The ancient punishment is amputation, but the king is merciful.

At his son’s wedding, Gregory tells him to keep away from his new wife. It is the first time harsh words have come between them.

The king makes his councillor a Knight of the Order of the Garter. He, Honest Tom of Putney. He rehearses the rites, then goes to bed early to think. Are we ready for the fat years? Are we ready for our charmed life?

His new kinswoman, Jane Seymour, does battle in the bed chamber and gives the kingdom its future king. But after Edward is christened and Cromwell is passed over for an earldom, the queen falters and fades. Lucky to be queen, her sister says, but unlucky to die for England.

Mistress Cromwell is already pregnant. He is to be a grandfather. ‘I would rather be alive, Bess says, than have a great name: would not you, Lord Cromwell?’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Henry VIII • Bess Seymour • Edward Seymour • Harry Percy • Richard Riche • John Husse • Richard Cromwell • Jane Seymour • Gregory • Dick Purser • Mathew • Lady Mary • Surrey • Thomas Wriothesley • Lord Exeter • Nicholas Carew • William Fitzwilliam • Gertrude • Suffolk • Norfolk • Francis Bryan • Tom Seymour • Rafe Sadler

This week’s theme: Jolly Tom from Putney

Henry turns and looks at him. ‘Always you, Cromwell, with the bad news.’

“The Image of the King” began in Lent, with a bloodthirsty Thurston dreaming of bacon and beef. ‘There are willing butchers, enough,’ he told his master. We cannot subsist on fish, cheese and eggs. ‘Naught but yellow and white.’

The chapter ends with a memory of butchers at Lambeth, disassembling beasts into dinner. He goes down to the kitchens at Windsor and is mistaken for a clerk, as men carry ‘cadavers the size of men … around the winding stair and guided by the sound of rushing waters, down into the dark.’

The downward spiral, ‘squishing the gore from their bloody boots’, contrasts with the rising prospects of ‘Jolly Tom from Putney’. His son has married the queen’s sister; he, himself, is now a Garter Knight. ‘It seems such a thing could never happen, not to Walter’s son. Yet so much has happened already, that the most credulous child would never believe.’'

The rebellion has passed; the queen is with child. So why do we feel so grim, so wretched? My son, Cromwell tells Bess Seymour, ‘is all together better than me.’

I, he thinks, who am so soiled in life’s battle, so seamed and scarred, so numb, so unwanted, so cold.

Cromwell has created an image of himself: terrifyingly competent, good-humoured and fearless. ‘The only things he cannot remember are the things he never knew.’

But that was before Dorothea, before Jenneke. When he became strange to himself. Before the cardinal went away; before Lady Mary looked through him, as if she didn’t know who he was. Before he found himself always approaching the king with bad news.

Henry makes him a knight, and hopes you live ‘many years to enjoy your new state.’ The king needs him. He says, ‘Spend your days with me.’ He says, ‘If I die before my time, Crumb, you must…’

Do it, he thinks. Draw up a paper. Make me regent.

But all the time, he thinks, the king is the ‘butcher bird, who sings in imitation of a harmless seed-eater to lure his prey, then impales it on a thorn and digests it at his leisure.’ England and the Earl of Surrey, even his beloved son Gregory, think he, Cromwell, is everything. Henry is his ‘minion’; he ‘has all to rule.’

But he knows he has failed the king. ‘It is Pole, he thinks.’ He promised he would get Reginald Pole, but he failed. And Henry hates men who break their promises. He gives his ministers freedom, but sets ‘a hedge of expectation around them, invisible but painful as blackthorn. You know when you have brushed against it.’

He has brushed against it.

The ‘fat years’ have come. His life is ‘charmed.’ But instead of joy, he thinks of flesh-hooks and the winding stair. He thinks of his father.

‘One night, drunk, Walter said to him, hand slapping his own breast: 'This boat is rowing and rowing, Thomas. I'm rowing to save my life.'

Footnotes

1. Elizabeth Seymour

‘I think there has been a misunderstanding. I am offering my person to one Cromwell only, the one I marry. But which Cromwell is it meant to be?’

The exchange between Thomas Cromwell and Elizabeth Seymour (Lady Oughtred) is one of the most memorable scenes in The Mirror and the Light. At the

, we were treated to a performance of this scene by Ben Miles (as Cromwell) and Aurora Dawson-Hunte, who played Bess Seymour in the stage adaptations. In a moment of sublime confusion, Ben Miles began reading Aurora’s lines as Lady Oughtred, adding one more layer to a conversation thick with misunderstanding.This conversation is the culmination of Cromwell’s private feelings of loneliness and longing directed at Jane’s sister. Back in 1536, Bess summed up Master Secretary’s dismal life, leaving him feeling mournfully understood and uncomfortably aroused:

He is struck by her overview of his situation. It is as if she has understood his life. He is taken by an impulse to clasp her hand and ask her to marry him ... He feels irredeemably sad. As if he has been plunged into mourning. And at the same time he feels, if someone tossed a feather bed into the room (which is unlikely) he would thow Bess on to it, and have to do with her.

He was glad she called herself Bess and not Liz, and he was surprised (he, who is never surprised) by her grasp of Latin. His confusion bled into the marriage negotiations and erupted in this exquisitely awkward scene in the queen’s privy gardens.

The marriage alliance makes Gregory’s father a kind of uncle to the king. It is a tenuous sort of kinship, but Diarmaid MacCulloch points out that ‘the most convincing of the generally unconvincing hereditary claims of the Tudors to the throne of England was the marriage of a king’s widow to her Steward, the Welshman Owain ap Maredudd ap Tewdwr: Henry VIII’s great-grandfather.’ Dynasties could be made with much less, and for a brief few months in 1537, the Cromwells had successfully bound themselves into a Tudor-Seymour royal family.

The alliance comes at a personal cost to Cromwell. The cold exchange with his son is the sequel to his meetings with Dorothea and Jenneke, mirroring monstrous reflections of his past and who he has become:

'So many words,' Gregory says. 'So many words and oaths and deeds, that when folk read of them in time to come they will hardly believe such a man as Lord Cromwell walked the earth. You do everything. You have everything. You are everything. So I beg you, grant me an inch of your broad earth, Father, and leave my wife to me.'

Further resources:

2. Mary of Guise

'The Duke of Longueville has died,' he says, 'leaving a widow – a very handsome woman, they say, only three years wed, yet with a son in her arms and another child in the womb. James might look that way.' But I don't know, he thinks, if she would look at James. The family of Marie de Guise are such lofty people they might not know where Scotland is.

There are so many widows and widowers in our story. Cromwell himself, Bess Oughtred, James V of Scotland and (very shortly and once again) Henry VIII of England. These two widower kings will vie for the hand of Mary of Guise. As Cromwell predicts, the French noblewoman will marry into Scotland and in 1554, she will become queen regent for her daughter, the ill-fated Mary, Queen of Scots. Henry VIII’s daughter, the ginger pig Eliza, will have her cousin Mary beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle, in 1560. At her death, she will wear red. In 1603, her son, James VI, will become James I, the first Stuart king of England.

Further reading:

3. Danaë visited by Zeus

This is no ordinary rain: the bride stands, complacent, as gold plummets down on her, and nuggets roll over her bare arms and thighs and pool as a pile of bullion around her ankles. Never was a lass so augmented; and no bruises either. Bess Seymour will recognise Danaë, and no doubt give her a nod.

Cromwell has moved on from comparing the Seymours to the incestuous heroes of the Greek legends. He showers wedding gifts on his son and daughter-in-law, making himself the cloudburst, Zeus, raining forth gold on the naked Danaë. If he cannot possess Bess Seymour, Cromwell will do so through allegory: Zeus’s golden rain conceived the child Perseus, founder of dynasties and slayer of monsters. His great-grandson, Hercules, was famous for his twelve labours, including the killing of the many-headed Hydra.

Though the Hydra was never a fair opponent. It lurked in caves, and could only be killed in daylight.

4. Plague-stricken brothers

But the watchmen see who holds the lights; it is the plague-striken brothers themselves, tiptoeing the cloisters in their stinking shrouds. They bring dispatches from the world beyond, apparently: they have seen the martyred Bishop Fisher, seated at the right hand of God.

In this chapter, we see the final grim end of the Carthusian order of monks in England. Their story has shadowed the trilogy. Thomas More spent time in the London Charterhouse, and Cromwell tried in vain to turn them away from Rome. Between 1535 and 1537, eighteen monks were killed for refusing to accept Henry as head of the church. This last group were starved to death in captivity or died of the plague, which was then spreading through London.

The plague outbreak limits Cromwell’s access to the king:

The king does not want to be without Cromwell, as the mornings grow misty and the first chill lies on the air. Come and be near me, he says. Spend your days with me. Maybe just, to keep to the rules, sleep under another roof a night. He obeys.

How closely this anticipates the flouting of social distancing restrictions by government officials during the Covid-19 Pandemic! A former UK prime minister would find an ally in Henry’s creative interpretation of the rules.

5. The image of the king

'There can be copies, Majesty,' Hans says, modestly. Mirrors of his lively image: ever larger, more active with every telling.

As I mentioned last week, the original mural in Whitehall was destroyed by a fire in the seventeenth century. However, it is one of the most reproduced royal portraits and the one most closely associated with Henry VIII. You can see some of these copies in the Wikipedia article for Hans Holbien’s painting. Some are more flattering than others.

6. The butcher’s dog and the butcher bird

A greyhound gift for Lady Mary creates the opportunity for a dramatic confrontation between the Howards and the Cromwells. This Shakespearean rivalry has something of the schoolyard about it, as Surrey trades insults with Cromwell’s clan:

‘When they told me of this match you have made I could scarce believe it – not even of you.’ 'He means me,' Gregory says. 'I am the match.' 'Aye, you,' Surrey says, 'you squat little clod.'

Size matters, and blood matters, as ‘spindle-shanks’ draws ‘vile blood’ in the precincts of the king. Cromwell was once the ‘butcher’s dog’, but now he owns the space around the king. ‘One by one,’ Surrey says, ‘you will cut off our heads till only vile blood is left in England.’ So why does he, Cromwell, not feel safe? Perhaps it is because he once served the cardinal, the mild-mannered son of a butcher. Now, his master is the king, a very different beast.

The king is like the shrike or butcher bird, who sings in imitation of a harmless seed-eater to lure his prey, then impales it on a thorn and digests it at his leisure.

It is August, 1537, and the king has been two years in his killing vein, with no sign of losing appetite for the slaughter.

7. The Portinaris

'I'm not going to pull it down. I'm going to blow it up.' 'Really?' The king looks respectful. 'I know an Italian. He is confident it can be done.' 'Come to me after supper,' Henry says. 'Bring drawings.' He looks as excited as a child.

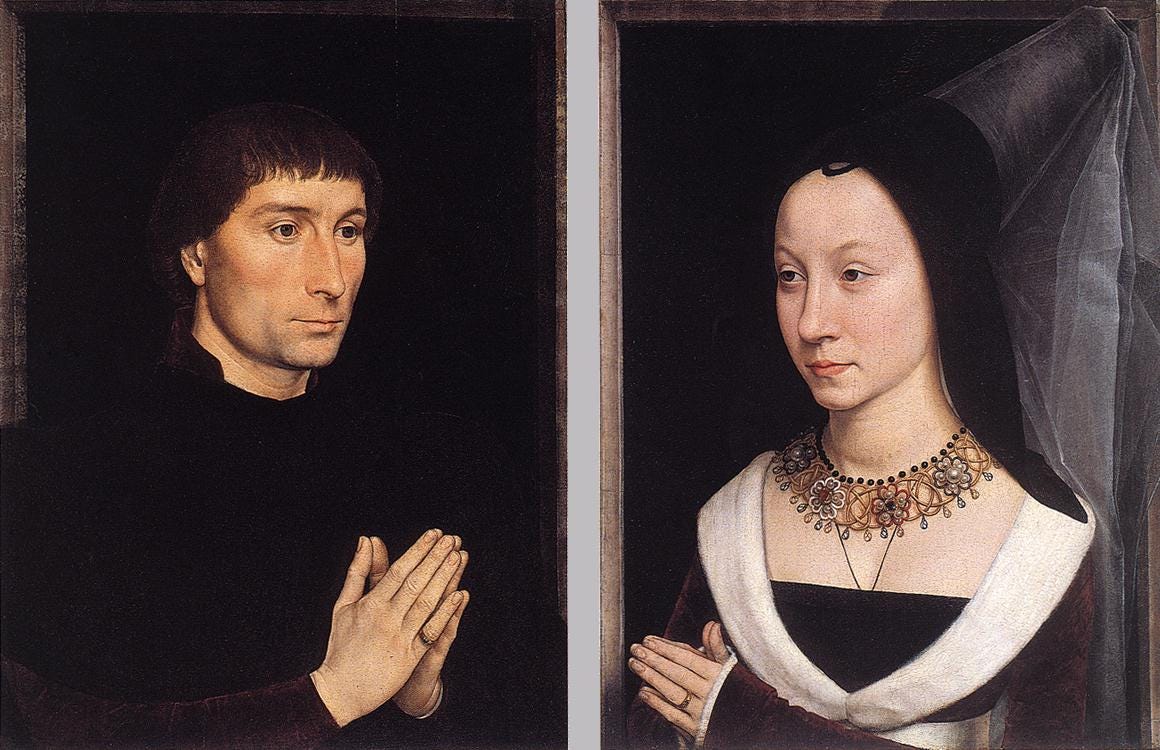

Cromwell knows how to cheer up his king. Tell him about ironworks, or war machines, or exploding things. Cromwell hires Giovanni Portinari to demolish Lewes Priory. Giovanni appeared briefly in one of his Italian flashbacks earlier in the trilogy. The Portinari were a prominent merchant family from Florence. They are mentioned in the next chapter, when Cromwell remembers the Nativity altarpiece commissioned by Tommaso Portinari in Bruges.

It is a painting with doors, which open on winter. Within its span, time collapses and many different things happen at once, that could not happen in an unblessed human life. In the painting the past is present, the future happens now.

This is a fair description of what Hilary Mantel achieves in her historical fiction: a Cromwellian present that is overlayed by past and future. Incidentally, Tommaso included himself in the altarpiece painting. See if you can find him.

Further reading:

8. He, Cromwell, Garter Knight

The gentlemen rustle in acknowledgement but cannot bring themselves, for a moment, to applaud. They knew it was going to happen. But they are still shocked. A brewer’s son: it takes time to get used to it.

So, within a few pages, the Putney boy becomes an uncle to the king and takes his place ‘among the illustrious knights’ of the Garter. ‘Those present, those absent. Those quick and those dead.’

It is enough to make you dizzy; it is enough to make you retire early to your bed and to your thoughts.

The names of all the knights are included in the Liber Niger, or the Black Book of the Order of the Garter. Cromwell’s name appears there, dated 5 August 1537. But above it, the canons of St George’s Chapel have dutifully inscribed the word proditor: traitor.

An archivist at St George’s elaborates:

When a Knight of the Garter was convicted of treason, he was ejected from the Order in a process known as degradation. His Garter, Collar and regalia would be taken off him, and a warrant would be issued ordering the removal of his achievements, the banner, helm and crest in St George’s Chapel. These would be thrown down into the quire, whereupon the Officers of Arms would kick the achievements out of the quire, through the Chapel, out the door, across the Lower Ward and into the Castle ditch as a demonstration of the unworthiness of the degraded knight. The stall plate would then be removed and often destroyed. This would have happened on the degradation of Thomas Cromwell in 1540.

Further reading:

9. Broken on the Body

On 12 October 1537, Edward Tudor was born at Hampton Court. The absence of a legitimate male heir has shaped our world until now. It broke Wolsey, and it made Cromwell. Edward secures the succession, the dynasty and the realm. But we are not victorious. The title refers to Cromwell’s sense of failure. The king knows his minister has taken a body blow, a lance ‘broken on the body’. He has failed to give his king the traitor Reginald Pole.

“Broken on the Body” also refers to Jane. The contrast is striking. In the previous chapter, the king was painted as something he wasn’t. His body was transformed and made eternal. In this chapter, Jane’s body is broken in delivering England its future king. And Hilary Mantel gives us one of the book’s most magisterial sections of prose, on the enormous risk endured by women in the Tudor era:

What is a woman’s life? Do not think, because she is not a man, she does not fight. The bedchamber is her tilting ground, where she shows her colours, and her theatre of war is the sealed room where she gives birth. She knows she may not come alive out of that bloody chamber. Before her lying-in, if she is prudent, she settles her affairs. If she dies, she will be lamented and forgotten. If the child dies, she will be blamed. If she lives, she must hide her wounds. Her injuries are secret, and her sisters talk about them behind the hand. It is Eve's sin, the long continuing punishment it incurred, that tears at her from the inside and shreds her. Whereas we bless an old soldier and give him alms, pitying his blind or limbless state, we do not make heroes of women mangled in the struggle to give birth. If she seems so injured that she can have no more children, we commiserate with her husband.

Jane may have contracted an infection due to her long difficult labour, which lasted two days and three nights. She died on 24 October and was buried on 12 November in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle.

Further resources:

The byrth of mankynde, otherwyse called the womans booke: The first book on pregnancy and childbirth printed in English.

Quote of the week: Unless you have a better idea?

When we were young, the future was everything we hadn’t seen, hadn’t touched, hadn’t felt. We were the boy in Putney, climbing ladders and watching ships sail down the river out into the world. We left home to escape a future that looked like our past, a past that looked like Walter.

At some point – we don’t know when – we forget how to reinvent ourselves. We stop making our future, and start saying: ‘If we can get through next winter.’ Or, like Wlater, drunk, we slap our breast and say: ‘This boat is rowing and rowing … I’m rowing to save my life.’

This present. This crest of the wave. This is it; all there is. And, ‘when I see ordinary happiness the horizon tilts and I see something else.’ I do everything. I have everything. I am everything. But it feels – I can not lie – it feels like nothing. No, worse than nothing.

Why does the future feel so much like the past, the uncanny clammy touch of it, the rustle of bridal sheet or shroud, the crackle of fire in a shuttered room? Like breath misting glass, like the nightingale’s trace on the air, like a wreath of incense, like vapour, like water, like scampering feet and laughter in the dark … furiously, he wills himself into sleep. But he is tired of trying to wake up different. In stories there are folk who, observed at dawn or dusk in some open, watery space, are seen to flit and twist in the air like spirits, or fledge leather wings through their flesh. Yet he is no such wizard. He is not a snake who can slip his skin. He is what the mirror makes when it assembles him each day: Jolly Tom from Putney. Unless you have a better idea?

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading ‘Nonsuch, Winter 1537–Spring 1538’. This runs from page 523 to 562 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “‘My lord?’ a boy says. ‘A gravedigger is here.” It ends: “… and the name of the palace is Nonsuch.”

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

It was so painful to read that exchange between Gregory and Cromwell. It's the first real disconnect they've had. This last book is full of surprisingly painful encounters: Dorothea, Cromwell slowly losing his standing with Henry, this exchange with Gregory. No wonder Cromwell gets so lost in his memories. They must be more comforting than the reality in front of him.

I've been meaning to write a testimonial for the last few weeks, so here it is:

When I first read the Cromwell trilogy, I grew to love it more with each book. But I loved it alone. Sure, I knew it was popular and that it had won all sorts of awards, but I was still in my own little Crumb bubble.

Getting to experience it again with other people who love it or are learning to love it brings out a whole new side of the story. I'm seeing things I hadn't noticed before and learning more about that time--the paintings are a great addition and further bring the world to life. The passion behind these posts is obvious and of such high caliber that I eagerly look forward to it each week. I will remember this year of slow reading for many years to come.

And it's just plain ol' fashioned fun :)

Thanks so much, Master Haisell!