📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 41 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the first part of ‘The Image of the King, Spring–Summer 1537’. This runs from page 437 to 477 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Hans does not like the pavonazzo’ It ends: ‘Legs that could never stagger, feet never lose the path.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Are you enjoying Wolf Crawl? I need your help!

This month, I will launch the 2025 slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. If you have enjoyed reading with us this year, I would love to hear from you. Your feedback will be enormously helpful for new readers deciding whether to join us in 2025. What were your expectations? What was your experience of reading slowly? What surprised you? And would you recommend this slow read? If you are happy for me to share your thoughts with future readers, please send me an email or a DM on Substack, or leave a comment below. Thank you so much for your time.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

The lean days of Lent, 1537. Hans Holbein insists the king must wear crimson for his painting. Thurston maintains that an Englishman is carnivorous. Give him red meat, or watch him waste away. He, Lord Privy Seal, dreams of retirement at Launde Abbey and of throttling the Bishop of Rome.

The court attends the christening of Edward Seymour’s daughter. John Husee brings news and shopping lists from his mistress, Lady Lisle, across the Narrow Sea. Lady Rochford brings news from Jane’s private chambers. A child is now expected.

Reginald Pole wants to meet him, so in council, he threatens to kill Pole himself. Fresh insurrection breaks out in the north, led by an old ally of his: Francis Bigod. But these are end times for the rebels. Aske is in the Tower, implicating Eustace Chapuys.

He gives Thomas Wyatt a diplomatic mission and takes a day off to walk in his garden, and have supper with Richard Riche. He makes arrangements of land for Bess Oughtred, until a happy thought comes to him: he will make Jane’s sister his daughter-in-law.

Hans Holbein paints the living king of England and forgets to bring a lute. Garter knights are dropping like flies, so Call-Me looks coy and tells Cromwell to order his mantles. Jane augments and dines on fat quails sent fresh from Calais.

A new imperial ambassador arrives in a diplomatic push to marry Lady Mary to Luís of Portugal. Cromwell stands by to make sure nothing happens.

In June, the king stands for another session with Hans. Henry encourages himself in hearty tones, but the damage has been done. We cannot go back to the place we were before. He staggers, he falls. Cromwell mentally picks up his king and turns his head, his whole body, to face us in the painting.

Our invincible, indestructible sovereign. The image of the king.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Hans Holbein • Henry VIII • Thurston • Mathew • Jane Seymour • Edward Seymour • Lady Mary • Nan Seymour • John Husse • Thomas Audley • Lady Rochford • Richard Riche • Thomas Wriothesley • Thomas Wyatt • Mercy Prior • William Fitzwilliam • Bess Seymour • Gregory • Diego de Mondezo • Chapuys

This week’s theme: Big fish

He greets Mary’s usher. ‘Big fish today.’ He speaks for everyone to hear. ‘A Spanish gentleman has come from the Emperor, to assist Ambassador Chapuys in wooing the Lady Mary.’

Always pay attention to what’s on the plate in Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. It is Lent, so red and white meat are off the table: we must eat fish and game. War on the seas means fish is scarce, so the king will also allow us eggs and cheese.

'Naught but yellow and white,' Thurston says.

Cromwell’s cook is back from fighting rebels. His grumbling is instructive: ‘Englishmen were never made to eat fish. Salt water gets in your brain … an Englishman is bred on bacon and beef.’

He’s not the only unhappy eater. ‘God forgive me,’ Cromwell says to Call-Me, ‘but I wonder why He ever made pike?’ Thurston tries ‘a new cod dish’ that ‘looks as if they’ve sicked it up.’

Thurston would likely blame a lack of red meat for the king’s ailing health. The queen imports quails from Calais, ‘cracking and sucking the tiny bones.’ The ‘jelly creature within her’ needs fattening up: you can’t grow a king on fish alone.

Cromwell is now a ‘big fish’ himself. Norfolk once accused him of being ‘a person’, but now this person dictates terms to lords: warning Arthur Plantagenet that he ‘will have him out of his post and at the gallows’ foot, if he tries to play me for a fool.’ He’s arranged a wife for Gregory that will make him, Tom of Wimbeldon, uncle to the king.

On the street, Londoners shout ‘Cromwell, king of London!’ and ‘his stomach lurches.’ No longer turning circles in a pond in Putney, he is now swimming with sharks. Just occasionally, he feels the watery depths beneath him, cold and dark.

Meanwhile, there is the matter of painting Henry. How do we dress up this pale king so he can ‘awe the whole world’? We paint him crimson. Blood red. In the country, repentant rebels are made to wear the red cross of St George, ‘a red ribbon, or sew a red thread that connects you to your sovereign.’ The king’s two bodies are sick and starved, but we must live a lie in England: we wear red and eat rashes, even if only in our minds:

'I've no strength to beat anybody,' Thurston says. 'An egg won't do it for me. I want a rib of beef. I could kill Christ for a taste of bacon. I reckon that was Eve's sin – she never erred for an apple, she went wrong for a fat rasher.'

Footnotes

1. Hans Holbein’s Whitehall Mural

The king has not decided yet what kind of portrait he wants. He might ask for anything, from a picture that covers a wall to a miniature you can hold in your palm. But he agrees to be crimson. Each ruby is a tiny kindling fire.

I wondered whether Hilary Mantel had over-egged the metaphor in that last line until I realised the painting was destroyed by a fire in 1698. The crimson picture dreams of its own immolation.

We know what the painting looked like because it was copied many times during Henry’s life and afterwards. It is the most significant painting from his reign; perhaps the most famous painting of an English king. It is a piece of perfect propaganda that transforms ‘the sick man’ (Mantel’s words) into a picture of health, bulging masculinity and a towering kingly presence.

As Mantel’s Hans notes, he gives Henry ‘an extra inch or so’ in the leg and ‘a generous wad of quilting’ for a codpiece. Part of Holbein’s cartoon survives, a full-sized outline used to transfer the image to the wall. He stands in front of his royal father in a traditional three-quarter view position.

Hilary Mantel invents the occasion that transforms this version of Henry into a ferocious head-on portrait. Only last year, Henry fell from his horse while jousting. Through Bring Up the Bodies and The Mirror and the Light, the king has become a wounded beast with a festering leg. Anyone who has held a pose for a portrait may know what it takes to stay still. Here, Henry falls. And he, Cromwell, seeks to erase the moment of frailty with an eternal amendment to Holbein’s sketch:

'Turn the head. Turn it full on. Make him look at us.' 'God in Heaven,' Hans says, 'that will be frightening. Turn body and all?' Frowning face and massive shoulders. Bloated waisted, padded cod. Legs like the pillars that hold the globe in place. Legs that could never stagger, feet never lose the path.'

Most of us discover Henry VIII first through this painting and its iterations. This is how we meet him: the giant king, looking straight at us. The image is designed to convey England’s strength to France and Spain.

But it is also a picture of Henry looking at us, Thomas Cromwell. This is the man who made us, the king we must meet every day, and the Henry who, when all is said and done, will come to kill us.

Further resources:

2. Launde Abbey

In the blink of an eye, in the space of an Ave, he is somewhere else: he is at Launde Abbey, on the cardinal's business: on a day of buzzing heat, a young fellow laughing with the monks in a garden. This abbey, where he ate honey scented with thyme, stands in the heart of England, far from the dangers of salt water. It basks in woods and fields, and summer or winter the air is sweet. When he visited for the cardinal he looked at figures as he was bidden, but he found it so blessed a spot that he could not see it through the grid or lattice of an account book. Now he thinks: I'll have Launde for myself, when its surrender comes. I'll build a house, and live there when I'm old, far from the court and council. It's time I had something I want.

The famed dissolution of the monasteries is underway: an enormous land transfer from the Church to the Laity, nobles and gentry. All this wealth flows through the Court of Augmentations under the watchful eye of the young father, Richard Riche. ‘Any increase in Riche’s benevolence is of public interest.’ A word in the right place, money in the right pocket, will land you and your descendants a fine manor house fit for a fat abbot or a worldly cardinal.

In 1540, Cromwell made a note in his papers: ‘Launde for myself.’

By giving Cromwell this 1537 daydream, Hilary Mantel tells us many things about our Thomas Cromwell. He’s already thinking about the complete end of monastic life in England. ‘Launde will not come down yet’, Riche tells him. ‘I can wait’, is his steely reply. It tells us that our Cromwell is not just a man who loves money (‘It is my favourite subject,’ he tells Edward Seymour), but a lover of gardens, sweet honey and sweet air. He apparently has everything, but he believes he does not yet have what he wants. What does he want? He pictures himself old, ‘far from court and council.’ Like Francis Weston and George Boleyn, he dares to dream he has a future to be fifty, sixty, seventy.

We will return to Launde before we are done.

3. Somerset House

Chester Place belongs to the ancient bishopric, and Seymour is even now wrangling over the lease. A shame if he has to move now he has had the ancestors painted, and the chapel reglazed at his own expense. Winter light filters through the plumage of the Seymour phoenix; the slumbering fire beneath the feathers is so deep a red you want to warm your hands at the glow. Glass angels coo and flutter: they hold tabors and shawms, scourges and crowns of thorns. Some hold hammer and nails, to nail God to the cross: Easter will arrive, and the Man of Sorrows must bleed.

Cromwell is not the only man looking to secure his inheritance. While he looks around for a good match for his widowed sister, Edward Seymour hopes to hold on to his London townhouse at Chester Place.

After Henry’s death, Edward became the Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector, uncle to the boy king, Edward VI. He was the most powerful man in England until a power struggle in the Council of Regency resulted in his execution in 1550. By then, he had begun a massive building project, turning Chester Place and surrounding buildings into a grand palace: Somerset House. Since 1550, it has been owned by the crown. Redesigned in 1776, it is a massive public building that stands on the Victoria Embankment on the north side of the Thames.

4. Lady Lisle and Anne Bassett

'In return for quails, and cherries when they are ripe, Jane agrees she will give a position in her household to one of Lady Lisle's daughters.

If you want to know why we hear so much about Lord and Lady Lisle, over in Calais, it is because they have left behind such a rich historical record. When Arthur Plantagenet was arrested in 1540 (only weeks before Cromwell joined him in the Tower), his letters and papers were seized by the crown. There are about 3,000 documents, and I am pretty confident Hilary Mantel has read every single one.

Significantly, the crown did not secure Cromwell’s papers. They were probably destroyed by his loyal servants as soon as they heard of his arrest. The result: Lord and Lady Lisle come in loud and clear through the centuries, while Cromwell is a will-o'-the-wisp on the wind for Mantel’s ghostwritten hand.

Lady Lisle’s daughter, Anne Bassett, comes to court as a lady-in-waiting for Queen Jane:

Anne Bassett must have finer linen, so fine the skin shows through. She needs a gable hood, and a girdle sewn thickly with pearls. When she reappears by the queen's side, it is with her hair hidden, her skull squeezed, and in a gown belonging to my lady Sussex.

Anne has arrived with her hair uncovered in a French hood, a little too reminiscent of the other Anne, bisected last May. Rumours will surround Anne Bassett. She may have been the king’s mistress at some point. As John Husee notes, he keeps a list of everything the Seymours’ have ‘so my lady can get the same.’

5. Antonello da Messina

‘I am not your enemy, you know,’ Hans says to him. ‘Even though I did paint you.’

Hans Holbein says his painting of Cromwell was a failure. ‘You should have been painted by some other master, a dead one, for God He Knows, you looked dead.’

His portraits of Cromwell and Henry are both acts of concealment. They hide the private man and show his public image. Cromwell’s face is carefully arranged; it gives us nothing. He looks away, his mind on the weighty affairs of state. And Henry’s sick body is hidden behind the image of the king.

Hans Holbein recommends a dead painter: Antonello da Messina:

He has seen this master's work. When Antonello painted the grandees of Venice, he captured the sceptical raised eyebrow, the flicker of a sour smile. But the Venetians didn't like his work; he knew too much about them.

Looking at these paintings, you can see why a man like Cromwell might think twice about commissioning Antonello to take his portrait.

6. I wish the cardinal were here.

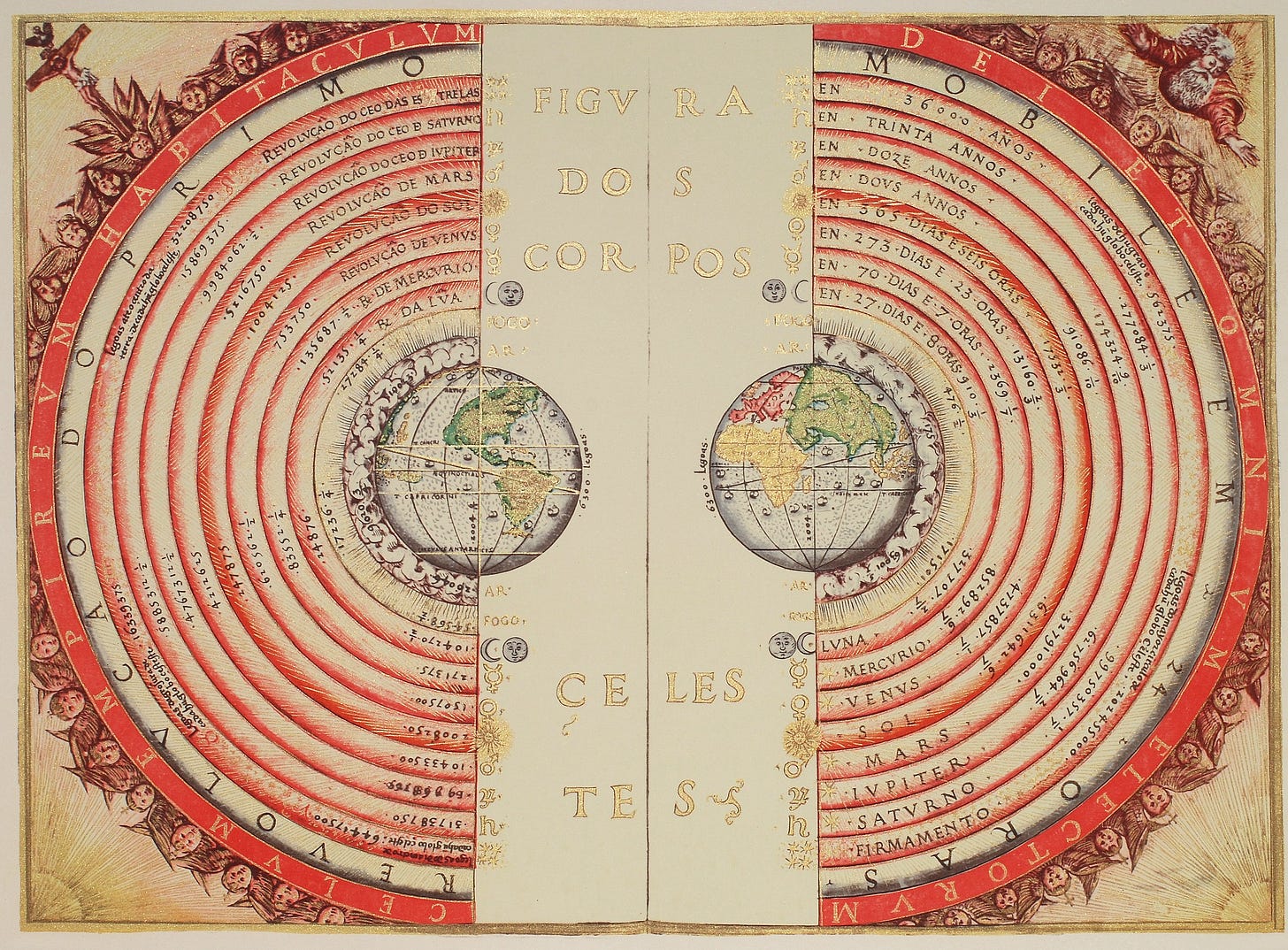

The noise recedes: laughter below; laughter above, perhaps, the cardinal applauding from somewhere beyond the primum mobile. The dead watch us, zealous in old causes.

The primum mobile is the outermost sphere in the medieval geocentric model of the universe, with Earth erroneously at its centre. Wolsey’s distant laughter is a reminder that the cardinal no longer appears close at Cromwell’s side. Wherever he is, he’s not with our Lord Privy Seal.

The cardinal had laboured long hours for this moment. The king would like him here to celebrate the good news. That Henry and Cromwell both miss the cardinal is something they share; a mirrored emotion in the half-light. What separates them is that Cromwell tried to save his old master, while it was the king, Henricus Rex, who killed him.

Quote of the week: A confusion of bodies

In ‘Vile Blood’, we see how Cromwell’s relationship with the king is like a marriage; he feels Henry’s loving embrace and senses the danger there: its stifling enclosure. Mantel reprises this image here with a mesmerising description of the two men working late into the night:

Sometimes, sitting beside the king – it is late, they are tired, he has been working since first light – he allows his body to confuse with that of Henry, so that their arms, lying contiguous, lose their form and become cloudy like thaw water. He imagines their fingertips graze, his mind meets the royal will: ink dribbles onto the paper. Sometimes the king nods into sleep. He sits by him scarcely breathing, careful as a nursemaid with a fractious brat. Then Henry starts, wakes, yawns; he says, as if he were to blame, 'It is midnight, master!' The past peels away: the king forgets he is 'my lord'; he forgets what he has made him. At dawn, and twilight, when the light is an oyster shell, and again at midnight, bodies change their shape and size, like cats who slide from dormer to gable and vanish into the murk.

This is Cromwell’s ‘image of the king’. It is intimate, close-up and frightening. He ‘allows his body to confuse with that of Henry’ and ‘imagines’ how ‘his mind meets the royal will’. These illusions are real: he is channelling the king’s power into dribbling ink. But they are also fiction: Cromwell is not the king. As he sits there, ‘scarcely breathing’, he must wonder how easily thoughts slip between duty and treason.

This is where we are, 1537, our sense of self spinning faster, changing shape and size, our mind always focused, on the image of the king.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the second part of ‘The Image of the King, Spring–Summer 1537’ followed by ‘Broken on the Body, London, Autumn 1537’. This runs from page 478 to 520 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘As July comes in Lord Latimer is down from the north.’ It ends: ‘My lord father, who will you let the king marry next?’

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

"Her voice runs on, rehearsing her gratitude. But she won’t look at him, he notices. her eyes are everywhere, but never on him."

"He thinks, Mary looks at me as if she doesn't know who I am."

What's going on here? I think Cromwell has tried to remind Mary she owes him, but then... princes do not like to be reminded that they owe anything to common men. And she will have spoken with the Poles and Courtenays. They have stiffened her heart against him. He has lost her, if he ever had her. And if he survives Henry, he won't survive Queen Mary Tudor.

On food, there is also a theme of sugar and sweetness: Thurston imaging the pope stuffing himself with sugar, while the English subsist on salted fish ('Salt water gets in the brain'). Cromwell's marzipan cake for the king at Easter, the sweet honey and sweet air of Launde, far from salt water. The sour smiles of the Venetians in the paintings of Antonello da Messina.