📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 40 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading ‘The Bleach Fields, Spring 1537’. This runs from page 399 to 435 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘When you become a great man’. It ends: ‘and somewhere it is written that Cromwell is his name.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Are you enjoying Wolf Crawl? I need your help!

This month, I will launch the 2025 slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. If you have enjoyed reading with us this year, I would love to hear from you. Your feedback will be enormously helpful for new readers deciding whether to join us in 2025. What were your expectations? What was your experience of reading slowly? What surprised you? And would you recommend this slow read? If you are happy for me to share your thoughts with future readers, please send me an email or a DM on Substack, or leave a comment below. Thank you so much for your time.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

Spring, 1537. A woman appears at his gates. She says she is from Stephen Vaughan’s household in Antwerp. Once inside, she recognises the woman in the weave on Cromwell’s wall. It is her mother, and she is Jenneke. Cromwell’s daughter.

When she leaves him, he speaks to Thomas Avery. He tells his accountant where his money is hidden, against the day his luck runs out and the dukes come to call.

Aske has written a little book. But while he, Lord Privy Seal, reads it, and the king talks of pardons, rebellion renews itself in the north. Rafe Sadler heads to Scotland on the king’s business, dodging Yorkshiremen as he goes.

Jenneke strips back her father’s memories. He remembers being the Italian in Antwerp and moving in with Anselma. In the present, he interviews the vicar of Louth in the Tower, while in Rome, Reginald Pole receives the cardinal’s hat.

His daughter unearths another Cromwell, lowering him into himself: back to a time when Lizzie lived. He remembers Walter before he died and his daughter Anne learning to read. Gregory’s bad dreams and Grace’s peacock wings.

Back in 1537, he must rescue his king from vanity as French merchants try to divert the royal war chest to a spending spree for Henry’s wardrobe. Aske goes north, where the rebels say, ‘Now forward on pain of death, forward now or else never.’

His daughter tells him of Tyndale’s death. He says, ‘It all goes back to More.’ Nothing ended when they killed More. ‘It only began.’ Pole’s treason. Tyndale’s burning. The north in rebellion. He ponders whether he can kill Pole with the same man More paid to capture Tyndale. Even in Utopia, someone has to shovel shit. ‘And somewhere it is written that Cromwell is his name.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Jenneke • Thomas Avery • Henry VIII • Rafe • Gregory • Thomas Wriothesley • Chapuys

This week’s theme: The original sin

'Christophe, wine for this young lady – will you take some wafers and spices, some raisins? An apple?' 'It was by eating of an apple that sin came into the world.'

The focus of this chapter is the unexpected appearance of Jenneke, Thomas Cromwell’s illegitimate daughter. Her mother, Anselma, is dead, and she has come from Antwerp to see her father and tell him about the death of William Tyndale.

Jenneke is one of the few fictional characters in the trilogy. As I’ll discuss below, Cromwell probably did have an illegitimate daughter, but Jenneke is entirely Mantel’s invention. Like Dorothea, she comes into the story to cast new light on Cromwell’s past and present.

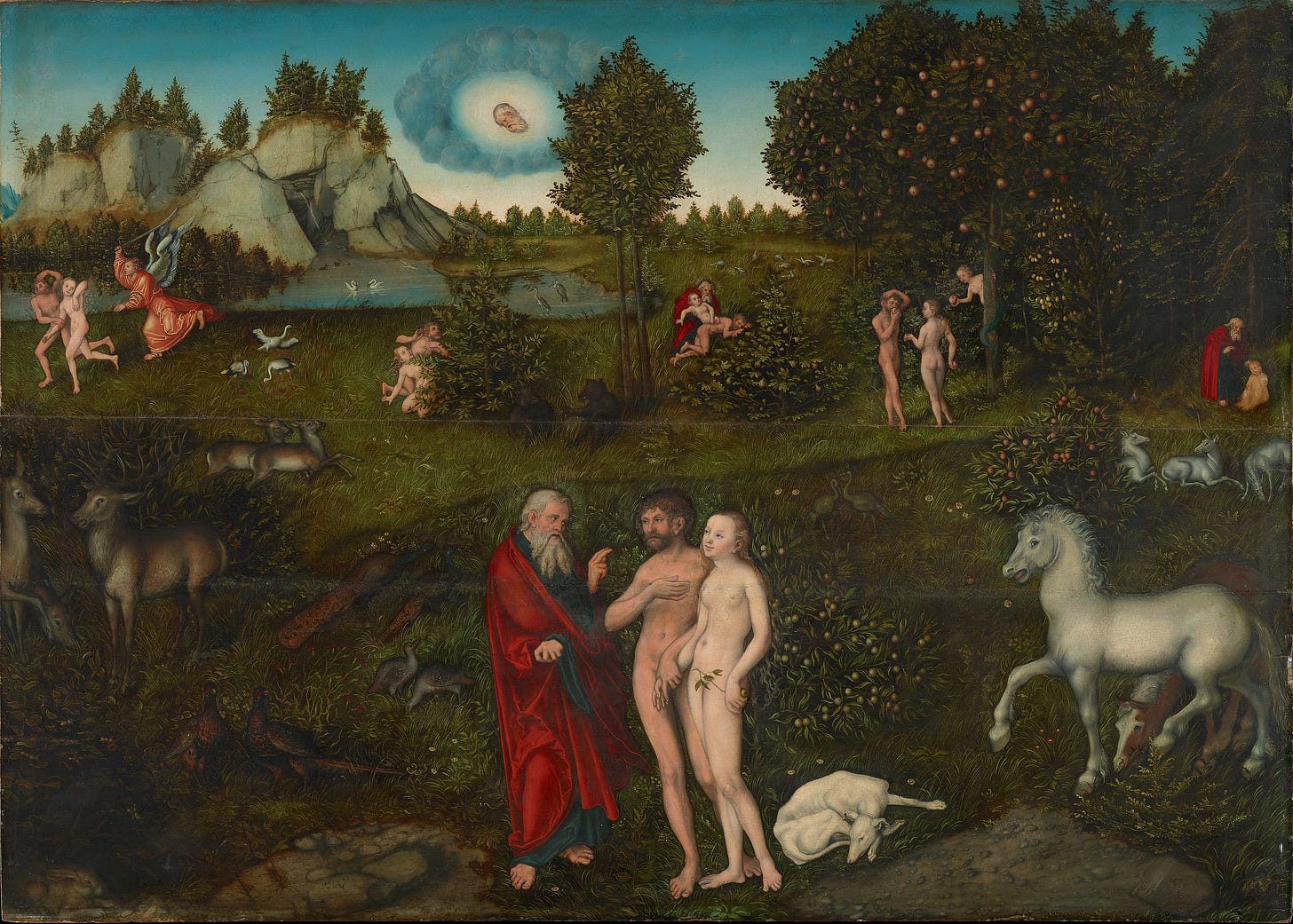

Jenneke reveals her identity while eating an apple that she compares to the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and were cast out of paradise. Jenneke gives Cromwell knowledge about himself, and for the second time in the book, he is shocked. It may be a stretch to call Cromwell’s preeminence a form of paradise, but Dorothea and Jenneke have conspired to cast him from his garden.

He thinks of Wolsey's daughter, knocking him back. He is not sure he has got up again.

Sin stalks the pages. As a ‘base’ daughter born out of wedlock, Jenneke is the embodiment of Cromwell’s sin with Anselma. ‘It is a stale sin,’ he tells Chapuys, ‘If it was ever a sin at all.’

Growing up, Cromwell was told that sins stored up extra time in Purgatory; prayers could shorten your sentence and fast-track your soul to salvation. When Cromwell returned from Europe, he found his father, a ‘new, reformed Walter’, a churchwarden with lawfully purchased land.

He believed in Purgatory in those days, and though he paid a priest to pray for Walter’s soul, he hoped Purgatory had a good strong lock on the door. He sees no need for Walter’s grandchildren to put him in their prayers.

The son wasn’t impressed by his father’s transformation. Cromwell has always positioned himself against Walter; he escaped Putney and his father’s brutality. ‘We not good enough for you?’ asks Walter. ‘No,’ replies his son. This memory reasserts and then undermines that narrative.

He has travelled a mile and more. But perhaps he isn’t that different from the mass of men.

He always wanted to be Walter, ‘but tidier.’ His father ‘patrolled his dreams’, and he still does: ‘sneering at him and fingering the king’s purple and silver curtains.’ His father’s sins are his own; his father’s dreams are his own. This story began with Walter’s words: ‘So now get up.’ He’s been following that command ever since.

What is sin? When he lived with Lizzie, ‘she kept a list of his sins, in the pocket of her apron: took it out and checked it from time to time.’ He lives long after her, not knowing whether he ever absolved himself of his failings; he suspects he did not. The greatest regret is that he saw so little of his daughter Grace, he ‘so often on the road, to provide for her future.’ She had none, no future; he lives with that memory, as sharp as sin:

Once, once only in all the nights, she had raised her head and looked at him from the darkness, her eyes open wide and the flicker of the candlelight inside them; perhaps she thought he was in her dream, as she was in his.

Since then, his sins have multiplied: ‘My list of sins is so extensive that the recording angel has run out of tablets, and sits in the corner with his quill blunted, wailing and ripping out his curls.’ Jenneke makes him embarrassed of his wealth, he tries to excuse it and explain it, but he knows in his heart, he wanted it: ‘Did I not have a doublet of purple satin, long before the cardinal came down?’

He must listen to the story of Tyndale’s death. He couldn’t stand the man, but he died for a cause he, Cromwell, believes in absolutely: the English Bible. Tyndale lived ‘like the poor apostles’ and died a martyr’s death. Now he ‘has put on the armour of light’ and joined the rest, men and women of virtue, their ‘human sins whited-out.’

Cromwell envies them. But envy is a sin, and he is a sinner. He must go on ( ‘Now forward on pain of death, forward now or else never.’), to plot Reginald Pole’s murder, make the king strong and rich, and shovel the shit in the republic of virtue.

Footnotes

1. A stale sin

‘You are aware that until this moment I did not know you lived?’

Jenneke is Mantel’s invention. However, the real Thomas Cromwell did have an illegitimate daughter called Jane. Traces of her remain in the historical record. In 1539, Cromwell paid for ‘apparel for mistress Jane’, then living with her half-brother Gregory. In 1580, the heralds called her the ‘base daughter of Thomas Cromwell.’ She married William Hough, the son of one of Cromwell’s servants, Richard Hough, evidently without the father’s consent. In his will, he complained that William had ‘married himself without his consent and goodwill to a stranger, not known who was her father.’

Diarmaid MacCulloch believes Jane may have been conceived in 1528–1529, in the uncertain months after the deaths of his wife and daughters and the fall of Thomas Wolsey. His life was collapsing around him and it was his time to ‘make or mar.’

Further reading:

2. The hidden picture

Her sectioned apple lies on her plate; he studies its green peel; he studies the plate beneath it, blue and white, Italian, the design half-hidden by the fruit. His mind completes the hidden picture.

When I read this, I immediately thought of Spode bone china and Blue Italian ceramics produced in England from the eighteenth century. These blue and white plates were ubiquitous in my childhood, and it is hard not to think that Hilary Mantel is deliberately evoking a vein of Englishness, the domestic and exotic entwined on the table, passed back through the centuries.

The moment is symbolic: Jenneke’s forbidden fruit half-hides the Italian design. Later in the chapter, ‘he sees himself then: sleek young Italian, face attentive, eyes busy. What’s left of that boy?’ He has to ‘complete the hidden picture’ of his Italian self, obscured now by the things he did in Antwerp and Austin Friars.

3. The woven woman

Anselma's woollen self has never aged. But he fears if she is carried too much across country, her features may fuzz and blur.

There’s something of The Picture of Dorian Gray about Cromwell’s woven woman. She has withheld her secret through the trilogy, until now. ‘Time to sail, Thomas,’ Anselma told him. ‘You are my past now, and I am yours.’ When he learns she is dead, ‘he consults his heart; it registers nothing, except the trace of the pen that, in the Book of Life, lightly inks a fate.’ On his wall is a reminder of the man he was and the other life he could have had: ‘a careworn couple, she purse-featured, he bald: but no doubt full of grace.’ Not the fat lord he has become, brimming with sin.

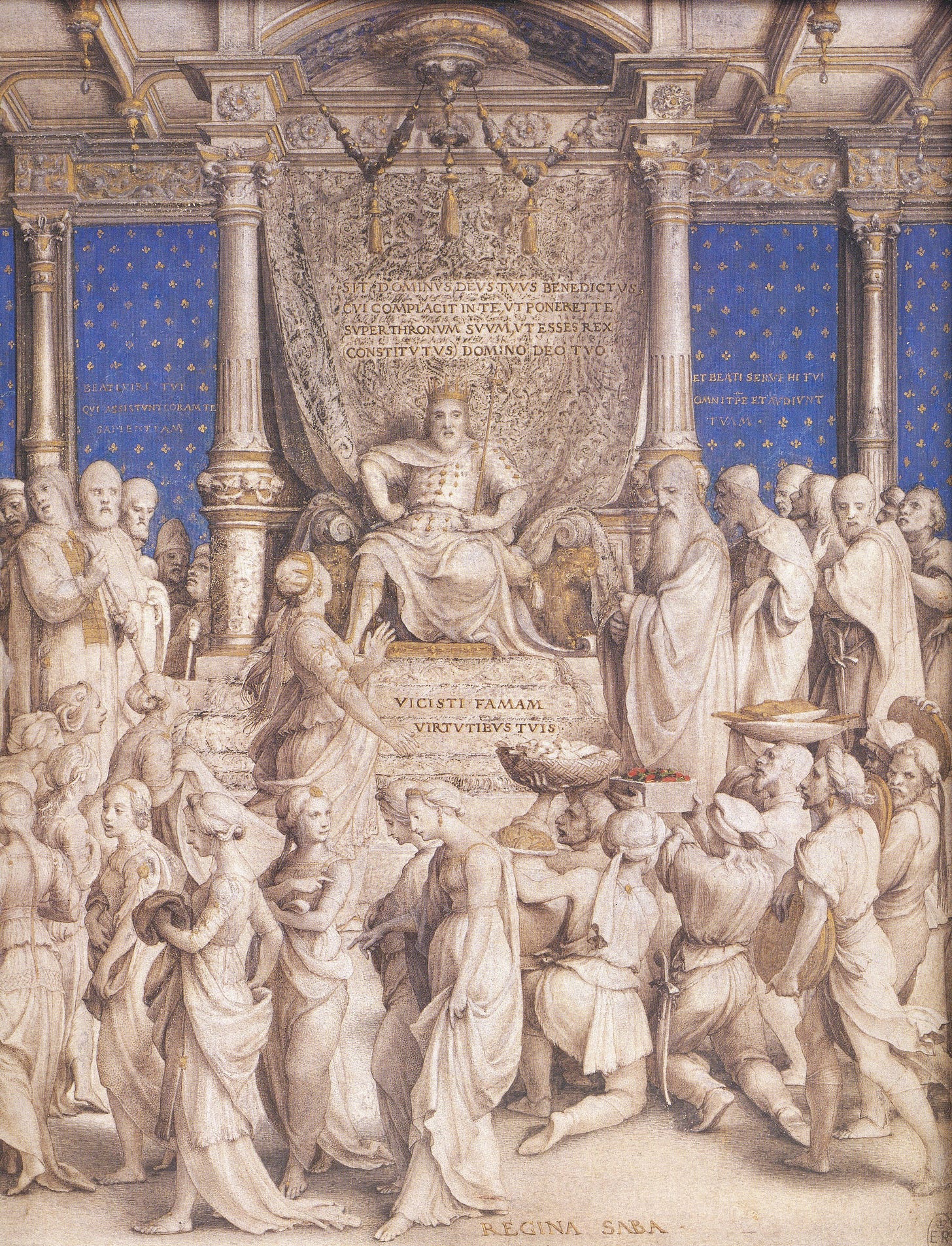

Cromwell refers to Hans Holbein’s painting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Holbein paints Solomon with ‘the face and garments of our own king’, his first image of Henry VIII. We see later in the chapter that the king has commissioned Holbein for a portrait painting: ‘The outer man, Henry knows, shows the inner man to the world; and if he knows it, how much more does Master Hans.’

This is why the king is buying new clothes. Cromwell has reason to think about how clothes show the inner man to the world. He wanted Jenneke to know he was happy in his lawyer’s black, but this was a lie: ‘I used it for concealment.’ Now, he is drawn to some ‘mulberry satin’ to ‘enliven’ his complexion. Call-Me says, ‘Be careful, sir.’ It is the colour of cardinals and ‘worldly prelates’.

Further reading:

4. Catastrophe

'It was a catatrophe,' she says. He is pleased that she knows the word. 'It started with one candle. All the timbers from the transept fell, and destroyed the chapels below. Some of us said it was God destroying idols.'

Jenneke tells Cromwell about the 1533 fire that gutted the cathedral in Antwerp. I like that he is pleased she knows a useful word like ‘catastrophe’. He notes that ‘the roof fell in’, a reoccurring image in the Cromwell books. And the observation that all it takes is ‘one candle’, should unnerve us all.

In 1352, work began on the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp. The largest Gothic church in modern Belgium was never completed. Jenneke saw divine judgement in the fire and her words are portentious. In 1566, an outburst of iconoclasm engulfed the Low Countries and a large part of the cathedral’s interior was torn down.

5. A crane called Thomas

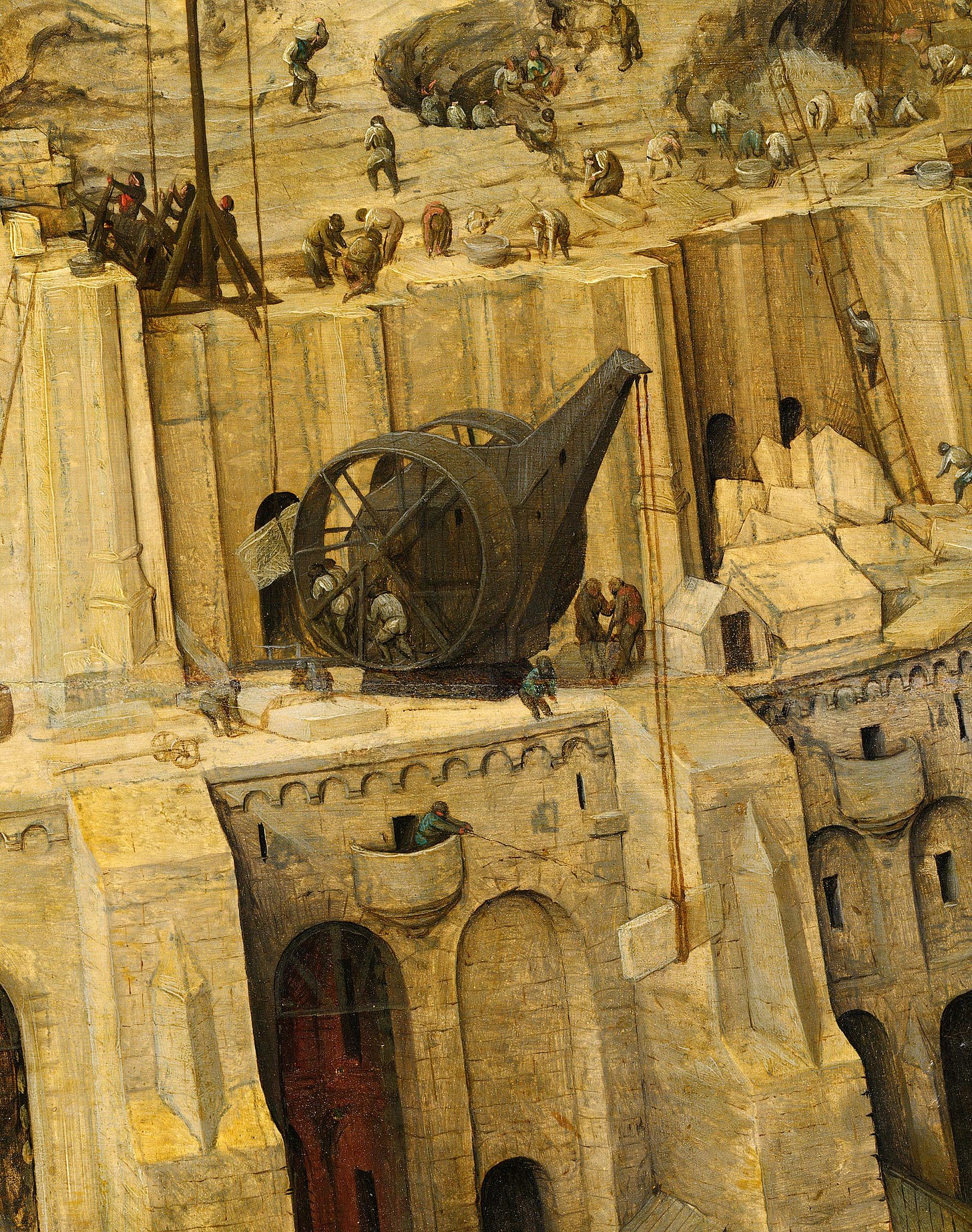

But he is a man who thinks about lifting heavy weights, about winches, beams and pulleys, and about joints, how to make them frictionless.

I love these colourful vignettes from Cromwell’s days in Antwerp. If you have read Dorothy Dunnett’s House of Niccolò books, you will recognise this picture of the cosmopolitan cityscapes of the early modern Low Countries. In Italy, he learned ‘cunning’, but in Antwerp, he learned ‘flexibility.’ And shopping! There is mention of the alum trade, which is critical to the dyeing of cloth to get those dangerous purple and red colours that he, Cromwell, finds so appealing. There are spices, cotton and silk, combs and – yes, of course – there are mirrors. Remember that some of these fine purchases will alarm Lizzie when he brings them to Austin Friars.

6. A sinner’s prayer

The church was bustling and noisy, but they could hear each other whisper: their heads close, her fingers sliding into his palm. Their breath mingled; she leaned against him, soft and warm. He said, 'Make me good, O Lord, but not yet.'

Saint Augustine’s wayward prayer picks up on this week’s theme of sin. Cromwell would like to be a more virtuous man, but he knows his weakness for good food, fine clothes and, most of all, power and prestige. But back then, his ‘vice’ was a simple one: love for an unmarried woman. Perhaps this was the day that Jenneke was conceived?

7. War machines

He goes to court: in his bag are plans for war machines. Better he has the king’s ear in these matters than Norfolk, whose ideas are old-fashioned.

The Mary Rose is the most famous English ship from the Tudor era. It sank in 1545 but was raised in 1982 and is on display at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. A 1536 document written by Thomas Cromwell states that The Mary Rose and six other ships were ‘made new’ in this year, paid for presumably by the influx of revenue coming in from the dissolution of the monasteries.

Mr Wriothesley grins. Warships: the message cannot fail to be carried home to France.

The redesign made it one of the earliest ships to fire a broadside, a coordinated volley of cannon fire from one side of the ship. ‘I mean to make her carry more ordnance’, boasts Henry. It is a hubristic threat: fighting the French in 1545, the ship took in water through its open gunports and sank. The chronicler Edward Hall wrote that the ship sank because of ‘too much folly… for she was laden with much ordinance.’ Out of a crew of 400, fewer than 35 men survived.

Further reading:

8. Tenterhooks

Jenneke impresses Cromwell with her English. But she does not know the term tenter-ground. After the fuller had washed the cloth, it was suspended on wooden frames for drying. The tenterhooks prevented the cloth from shrinking. Not only do these frames suggest some kind of medieval torture device, but they give us the expression ‘on tenterhooks’ for being in a state of nervous tension. It is a perfect Mantel metaphor, an unsettling twine of terror and fabric.

Jenneke confuses the tenter-ground with the bleach field, where cloth is whitened in the sun. Bleachfields were common before the invention of chlorine-based bleaching powders in the late eighteenth century.

But she has put in his mind an image of Tyndale strolling in the open air, the ground dissolving into a pale radiance, the city walls whispering into vapour, his shabby cross-grained countryman transfigured, and Meester Vaughan beside him, hood pulled up, his secret instructions hugged to his heart.

The tenter-ground and the bleach field appear to be metaphors for what is happening to Cromwell in the third book. His memories have been brought out of the dark and stretched on hooks. They have been set out in sunlight to be bleached white. The master of the shadows, of concealment and dissimulation, is exposed to the light of day. The cloth, now spun, must be finished.

9. Thomas More: Terrible to heretics

Sometimes it is years before we can see who are the heroes in an affair and who are the victims. Martyrs don't reckon with the results of their actions. How can they, when their mind is only on how to endure pain?

Cromwell is thinking of William Tyndale, but also Thomas More, the man for all seasons. ‘The name hovers at everyone’s lips these day, you would hardly think the man dead.’ More has reached out of his grave and pulled Tyndale into the fire. Everything comes back to More, and Cromwell regrets not killing him sooner. It is an unsettling conclusion.

10. Back again

We don’t know whether Cromwell travelled to the Holy Land. Hilary Mantel put him in Cyprus in one of his memories in Wolf Hall. She nudges him eastward to Palestine, on Frescobaldi business, to see the tomb of Lazarus near the village of Bethany. Chapuys thinks of Lazarus and wonders: ‘Was he truly welcome?’

It has crossed his mind before now. Were his family pleased to see him, or did they think he had been too self-important, in violating the laws of nature?

This is the premise of a fascinating book by Colm Tóibín called The Testament of Mary, where Christ’s mother witnesses Lazarus’ family’s dismay at his unwanted resurrection. The revived Lazarus is a husk of a human, his knowledge of death haunting him. Cromwell considers the tomb as ‘proof that miracles do not last.’

The crippled man walks, but only twice around the churchyard before he collapses in a flailing of limbs. The blind man sees, but the faces he knew in his young days are altered; and when he asks for a mirror, he doesn’t recognise himself at all.

Mirrors and memories: Cromwell is being made strange to himself, and to us.

Quote of the week: Last season’s blood

He thinks of Tyndale in the bleach fields, his human sins whited-out, speaking from within a haze of smoke. He thinks of the river at Advent, its frozen path. There is a poet who writes of winter wars, where sound is frozen. The soil beneath the snow seals in the noise of stampeding feet, the clank of harness, the pleas of prisoners, the groans of the dying. When the first rays of spring warm the ground, the misery begins to thaw. Groans and cries are unloosed, and last season's blood makes the waters foul.

Does anyone know which poet Cromwell and Mantel are referring to?

Last season’s blood is all the murder, from Thomas More and John Fisher to Anne Boleyn and William Tyndale. The killing time of 1535 and 1536. And further back to Little Bilney, John Frith, and Joan Boughton. The blood mingles with older memories: Anselma and the eel boy. The dead are crowding us out.

Thomas More wrote of Utopia, literally the ‘no-place’ of perfect government. Would there be a place for Cromwell in Utopia? He thinks so.

Somewhere – or Nowhere, perhaps – there is a society ruled by philosophers. They have clean hands and pure hearts. But even in the metropolis of light there are middens and manure-heaps, swarming with flies. Even in the republic of virtue you need a man who will shovel up the shit, and somewhere it is written that Cromwell is his name.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the first part of ‘The Image of the King, Spring–Summer 1537’. This runs from page 437 to 477 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Hans does not like the pavonazzo’ It ends: ‘Legs that could never stagger, feet never lose the path.’

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

I'd forgotten all about the arrival of Jenneke. I love these sent-to-the-nuns daughters showing up. First Dorothea, who as you noted, knocked him back, making him take another look at his actions during Wolsey's fall. Now Jenneke, who is making him think about his early life and what he left behind and what he's gotten in exchange. All through the books, his attention to women - the things they notice, the things that matter to them, has served him. He seemed even a little smug in his ability to read them/learn from them from time to time. Now - these two young women are showing him himself and how little he sees/knows that women notice, know, and even hide. That said, I'd love a peak at the list of his sins Lizzie kept in her apron pocket. :)

I think one of the things that makes Cromwell difficult to pin down is that no one is sure whom he serves - who is his master in the end? Himself? I think it's clear that H is his master but - with all the backroom deals and treachery - all the shit-shovelling - he performs in H's service - people imagine him to be without morals and therefore untrustworthy. Whereas, he seems to be very loyal - first to Wolsey, then to Henry. He says to Jenneke of H: 'Who else should I serve? A man cannot be masterless.'