Vile Blood (2/2)

Wolf Crawl Week 39: Monday 23 September – Sunday 29 September

This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 39 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the second half of ‘Vile Blood, London, Autumn–Winter 1536’ This runs from page 356 to 395 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Bess Darrell is a flitting presence by candlelight.’ It ends: ‘Try and keep cheerful.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Are you enjoying Wolf Crawl? I need your help!

I will run this slow read again in 2025 for paid subscribers. Soon, I will begin advertising Wolf Crawl and I would like to share testimonials from this year’s readers. What has been your experience? How did it compare to how you usually read? Would you recommend the read-along to others? I will be delighted if you are able to take the time to write something to help others decide whether this slow read is for them. You can send me a DM on Substack, leave a comment or hit reply to send me an email. Thank you so much for all your support.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

He catches up with his spy among the Poles and the Courtenays, Bess Darrell. The old families have been discreet, abusing Lord Cromwell always, but the king, never. He, Cromwell, is summoned at a late hour to see Lady Mary. The king’s daughter is keeping her distance, from the rebels and from the vile blood of Thomas Cromwell.

A memory from forty years back: how to make sweet treats from summer berries ‘to tempt the jaded palate’ of the winter king. He, Henry Tudor, is melancholy and lonely. He accompanies himself on the lute. It is the Cromwells’ job, father and son, not to laugh.

The Pilgrims take Hull. Lord Darcy surrenders Pontefract Castle. Norfolk hurries north to negotiate, to buy time before winter. Down in the kitchens at Windsor, Cromwell finds Patch playing with a ball. ‘Your head,’ he says, as he sends it over the wall.

He is studying his Greek, he is sleepless. In November, Robert Packington is shot in the mist on his way to Mass. A gospeller is gunned down in London, and Robert Barnes gives the eulogy. Cromwell has no choice but to lock Barnes up for his own safety. While at the Tower, he drops in on Tom Truth to read him some poetry.

Cromwell plants an idea in the king’s mind to invite the Pilgrims to Christmas. He, vile blood, makes himself scarce at Stepney. There, he admires his apple trees while the gardeners warn him off climbing any ladders. Alone, he amends The Book Called Henry. 'Do not turn your back on the king,’ he advises. And try and keep cheerful.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Bess Darrell • Jane Rochford • Lady Mary • Christophe • Henry VIII • Gregory • Rafe • Thomas Wriothesley • Sexton • Packington • Stephen Vaughan • Robert Barnes - Thomas Avery • Martin • Tom Truth • Richard Riche • Richard Cromwell • Chapuys

This week’s theme: The King and I

The king has given him a set of covers and bed hangings, purple woven with silver tissue, emblazoned with the royal arms. You are mine asleep or awake, Henry is saying: like a lover.

The intimate relationship between the king and his minister is under the microscope this week. Who will marry Lord Cromwell? There is a startling moment in a mirror, when Lady Mary’s face stares back at him, with her heart in her mouth. He says:

‘Would you not like to marry an Englishman?’ 'Who?' The question jumps out at him.

Read her lips, and the word ‘who’ sounds and looks a lot like ‘you’. It is enough to make your head heavy upon your shoulders. ‘Let’s leave it there.’ They are saying in the north that Cromwell wants to marry Meg Douglas, the king’s niece. ‘I tell everyone,’ says the king, ‘Cromwell would not presume. Not even in his dreams.’ Instead, Rafe proposes Kate Parr.

'Shame on you!' he says. 'When you know I am pledged to the Lady Mary, and to Margaret Douglas. I swear I will not marry below royal degree.'

The irony is that Katherine Parr will be royal when she marries Henry VIII in 1543. Cromwell will never re-marry, and his statement here seems to allude to both Mary I and Elizabeth I’s assertion that they need not marry, for they were married to England. And then there is another implication in Cromwell’s words: he is already married to a royal. He is married to the king.

The rebels make much of the idea. They compare Cromwell to Edward II’s favourite, Piers Gaveston. Many believed that Edward and Gaveston were lovers. Cromwell notes that people did not hate Gaveston because of ‘any unnatural vices’ but because ‘he was base-born’ – although not as base-born as Thomas Cromwell.

As Richard Riche observes, Henry would not use the Lord Privy Seal as a ‘catamite’. However, their relationship is increasingly intimate. The king calls upon him at all hours to divulge his melancholy memories of childhood and dredge his vast, unfathomable wells of self-pity. The king says, ‘I have my share of human vanity.’ He, Cromwell, ‘is afraid Gregory will laugh.’

Like a loving partner, he knows how to listen. Thomas Wriothesley, understudy, thinks Cromwell has been rendered speechless. ‘You were at a loss there,’ he says. No, not true. ‘He has mastered silence, but to better effect than More.’ ‘There is a time to be silent. There is a time to talk for your life.’ Call-Me’s misapprehension is why Cromwell will not give him, or Richard Riche, The Book Called Henry. ‘I doubt if there is much I can teach them. Or much they can learn.’

Thomas More had said once, can a king be your friend?

He, Cromwell, pictures himself as the Fox who trembled in the presence of the Lion. He crept forward, ‘And what did I see? I saw his solitude.’ He offers the king companionship, a partner to carry ‘the burden of kingship.’ Practically, by doing all the bloody and boring work; and emotionally, by being here for him, in the king’s chamber, where ‘two hours’ feels like ‘seven centuries’.

The king sings in Spanish. He is ‘a mountain girl’, ‘the dark girl, the rose without thorn.’ His lover, listener, Thomas Cromwell, is not fooled: the king has thorns. ‘Keep your eyes clear,’ he writes in The Book Called Henry. ‘Remember he is a king first and a man second… Do not turn your back on the king. This is not just a matter of protocol.’

The king adorns Cromwell’s bed with the royal arms; we follow the king as he retires to his own bed.1 Eight yeomen prick his straw mattress with daggers, roll upon it until they ‘are satisfied there is nothing sharp or noxious beneath,’ and pummel the feathers so you can ‘hear the steady thud of fist on down.’ The ritual is a confusion of sound and motion: sexual and violent. It precedes that other ritual of the king’s procession to the queen’s chambers, where the gentlemen try not to think of ‘her blushes and sighs’ and ‘his sweat while he ruts.’

The king’s embrace. No wonder, one must ‘try and keep cheerful’. Bess Darrell says ‘blood’ is ‘the precipitation of our age.’ A member of Parliament is shot down in the street, and he, Cromwell, ‘is told he is not safe in his own streets – not in his own house, not in his own bed,

where Walter stands at the bedpost, sneering at him and fingering the king’s purple and silver cutains.

His father’s ghost taunts his son, the king’s catemite. However, he is not afraid. ‘He feels a fierce exultation.’ He feels invincible. ‘He feels light, no plate armour, no chain links, only the knife under his shirt.’ He thinks of the king, a sword by his bed. For, ‘in the last instance, a king must defend himself.’

Further resources:

Footnotes

1. Melancholia, Black Bile

The songs tonight are Spanish: a boy sings about contests with the Moors, airs less martial than melancholy. Messages are brought to the Moorish king: God keep your Majesty, here is bad news.

The tune is “De Antequera sale el moro”. It is quite beautiful, and you can listen to it here:

The air of melancholy hangs over this chapter. Melancholia comes from the Greek word for black bile, one of the four temperaments or humours in medieval medicine. An excess of black bile was associated with depression, delusions, lack of appetite and sleeplessness.

The lack of appetite is alluded to by way of a forty-year detour to Lambeth Palace and Cromwell’s apprenticeship in the kitchens. Uncle John says, ‘Nothing is so green as a summer in England, Thomas.’ Hilary Mantel had lived in Botswana and Saudi Arabia. As someone who has also lived abroad, I felt this line deep in my melancholic spleen: ‘Those who have voyaged yearn for it. They dream of a bowl such as this.’

On the silk road; in the heat of the plains where neither rill nor brook trickles in three days' march; in the fortified towns of barbarians, where you can cook an egg by cracking it on the stones; in the places at the edge of the map, where the lines blur and the paper frays: by Mother Mary, says the traveller, by the maidenhead of St Agatha, I wish I were in Lambeth and had a dish of gooseberies and a spoon.

Summer is a season, a country and a kingdom. November 1536 feels like a place on the ‘edge of the map’ where ‘the idea of summer has dropped out of the world’, and we must ‘tempt the jaded palate’ of a melancholic king.

Remember that earlier in the year, in happier times, the king dressed as a Turk. Now, he sings sad songs of medieval Spain with bad news winding its way to a Moorish king. In high and low spirits, the king cloaks himself in an oriental costume.

Further reading:

2. ‘He must lie for his country’s good.’

Like the old king’s ministers, he labours day and night for his prince’s increase. The Italian Niccolò says that when a prince has such a servant, he should treat him with respect and kindness, advance him to honours and promote his fortune. Perhaps when the book is put into English our prince will read it.

Cromwell describes the frescos of Good and Bad Government by Ambriogio Lorenzetti, which one can still view in Siena today. He thinks about the Italian Niccolò Machiavelli and his book, The Prince. Cromwell read it back in Wolf Hall.

Someone says to him, what is in your little book? and he says, a few aphorisms, a few truisms, nothing we didn’t know before.

He is working on his own book, The Book Called Henry. He will not give this guide to Richard Riche, who he calls Ricardo because he studies Machiavelli a little too literally. Ricardo ‘understands that there are sins that governors may, perhaps must, commit… We do not need a translation from the Italian, to understand that.’

Further resources:

3. Make haste slowly

As we reach the end of 1536, I am aware of how far we have come and how close we are to the end. If I squint, I can see a fine web of rules set about us. Aphorisms and codes of protocol. To survive, we must know when to stand and when to kneel. When to stay silent and when ‘to talk for your life.’ Some of these rules are stored in The Book Called Henry. Others, we carry on our body: memories of bruises and burns and broken bones. If we forget one of these rules, even for a moment: we are dead.

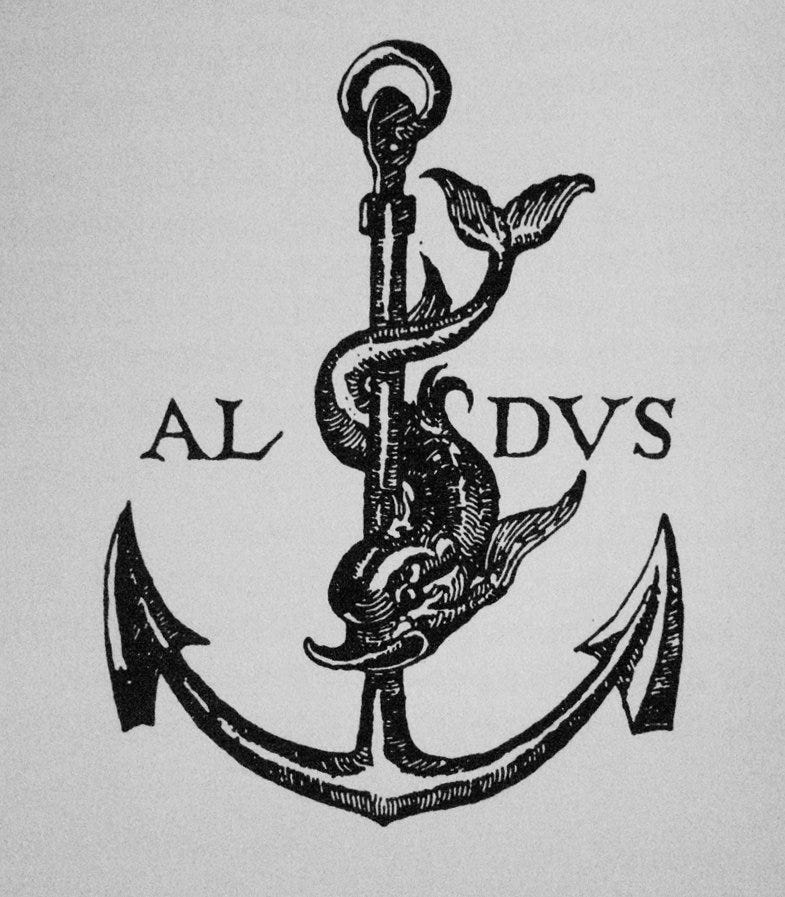

Cromwell recalls a book he bought, ‘long ago in Venice.’ It bore the imprint of Aldus: a dolphin-and-anchor, associated with the motto festina lente, meaning ‘make haste slowly.’ When Erasmus included it in his book of proverbs, he complimented the printer: ‘Aldus, making haste slowly, has acquired as much gold as he has reputation, and richly deserves both.’ Cromwell hopes ‘Erasmus will not rise, to write more books.’

He, Cromwell, has been slowly making haste, deliberately and diligently gathering land, titles, power; overturning old laws and making new ones; studying his Greek:

He says, 'I learned that ars longa, vita brevis: I learned how to say it in Greek.'

Skill takes time and life is short. Ask Robert Packington, mercer. Well, ask his ghost. London’s first victim of assassination by handgun. In the Tower, Cromwell stops to talk to Martin. ‘I trust it shall be many a day before I see you here,’ says the gaoler. Cromwell himself has said, ‘I ought to get myself locked up… Then I might learn a thing or two.’ It is not as though he doesn’t see his end. It is just that his future flits by candlelight, around corners and out of sight. Like the Cornish giant, Bolster. ‘Wherever you arrive, he has arrived first.’

He writes:

Never enter a contest of wills with the king.

4. Cromwell, the giant’s errand boy

When you are a child you think you have to kill the giant, but as you grow up you think different. Suppose you meet him by chance one day: you about your common business, picking up sticks or inspecting your rabbit traps, and he taking the air at the entrance to his cave, or toiling on a mountainside to uproot great oaks. Giants are lonely; they don't know any other giants. Sometimes they want a boy like Jack to amuse them, to run errands and teach them songs.

More giants in this week’s chapter. More Bolster. British folklore is full of giants. In the trilogy, the giants appear at the beginning of An Occult History of Britain: ‘Whichever way you look at it, it all begins in slaughter.’ Now, Cromwell appears to identify the king, kingship and the kingdom with the giants: ‘It’s here at Windsor, the swollen Thames surging under your walls, the water gurgling in downspouts and ditches – it’s here, after all the years, you find your confluence.’

He tells Robert Barnes, ‘Nothing about killing interests me.’ To believe this, we must put aside the events of this spring and summer. Or regard them in a different light. But this is how he sees himself: ‘sprightly Jack’ who has learned a less murderous, more efficacious way to tame and tempt the giant. Barnes calls Henry, ‘our dread sovereign’, but Cromwell thinks he can lure the giant-king away from the ‘priest in the head’ and towards true religion. It sounds like ‘a contest of wills with the king’, a course of action he has advised himself against in The Book Called Henry.

Further reading:

Quote of the week: Is a prince even human?

We began by wondering whether the king is our lover. We end the year 1536, dreading the giant, Henry Tudor, as he moves like Bolster, from west to east:

A shaft of light makes its way over the fallen snow, picking a path to the year ahead. The court rides through the city of Westminster and east to Greenwich, a moving trail of darkness against the frost. The Thames ia a long glimmer of ice: a road in a frozen desert, a trail into our future, a highway for our God.

In this chapter, something subterranean has breached the surface. A long time ago, at Calais, in Cyrpus, in Antwerp, we could have walked away. ‘I could have been a Frenchman like you,’ he tells Christophe. Or led ‘a safer life in Constantinople.’ Gone east instead of west. Picked another prince. But here we are, at the end of the year, ‘distilled to a single heartbeat, to the instant of the cut’. Now, the king has chosen to preserve our vile blood against the rebels. We are still alive and free because we, more than anyone alive, understand the king and what he is. ‘Keep your eyes clear.’ Do not turn your back.

You think of the prince as living on an exalted plane, finer and higher than other men. But perhaps Gregory has a point: is a prince even human? If you add him up, does the total make a man? He is made of shards and broken fragments of the past, of prophecies and of the dreams of his ancestral line. The tides of history break inside him, their current threatens to carry him away. His blood is not his own, but ancient blood. His dreams are not his own, but the dreams of all England: the dark forest, deserted heath; the stir in the leaves, the dragon's footprint; the hand breaking the waters of a lake. His forefathers interrupt his sleep to catigate, to warn, to shake their heads in mute disappointment. At a prince's coronation, God transfigures him, his human faults falling away, his human capacities increased; but that burst of light has to last him. That instant's transfusion of grace must sustain him for thirty years, forty years, for the rest of his mortal life.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading ‘The Bleach Fields, Spring 1537’. This runs from page 399 to 435 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘When you become a great man’ It ends: ‘and somewhere it is written that Cromwell is his name.’

Before I go, a reminder that I am looking for testimonials to recommend this read-along to readers joining us in 2025. If you can help, just drop me a DM on Substack, send me an email or leave a comment below. And if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Notice how this description of the king’s night rituals is the sequel to his dressing described in last week’s reading. The making and unmaking of a king.

"What survives from this year past? Rafe's garden at midsummer, the lusty cries of the child Thomas issuing from an open window; Helen's tender face. The ambassador in his tower at Canonbury, fading into twilight. Night falling on the rock of Windsor Castle, as on a mountain slope."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouldwarp

"The ignorant and fantastical people of the north say Henry is the Mouldwarp, the king that was and the king to come. He is a thousand years old, a rough and scaly man, chill like a brute from the sea... When you think of him, fear touches you in the pit of the stomach; it is an old fear, a dragon fear; it is from childhood."