This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 38 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the first half of ‘Vile Blood, London, Autumn–Winter 1536’ This runs from page 321 to 355 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Aske: he is a petty gentleman…’ It ends: ‘I could smell him from here.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

The north is rising, a rebellion led by Robert Aske and calling itself the Pilgrimage of Grace. They want the king’s council drained of vile blood, by which they mean Thomas Cromwell. He leads the response from Windsor, while beyond London, versions of himself become stranger and more ghoulish.

The queen asks him how to petition the king to bring Lady Mary back to court. In private, she looks for advice on the nature of the king’s dreams. The king’s dead brother, she says, has returned again to haunt him.

Jane’s request to Henry is made at court. She starts well enough, but soon strays into dangerous territory: she asks for the return of popery and an easing of the tax burden. Her family rescue her as Henry’s blood boils. Cromwell thinks, who has put these words in her mouth?

England is collapsing. As the rebels move on York, the king’s body grows sicker. Henry idles away his hours with Gregory, past jousts and talk of Merlin. The king feels betrayed but trusts his vile blood, his mushroom men, his Thomas Cromwell.

Norfolk and Surrey are sent north. He writes to his nephew to warn Richard to stay out of their way. He remembers being a boy when the Cornishmen came with the giant Bolster, who no one ever saw. He remembers how his uncle John helped him escape Putney and learn a trade.

York falls. The king goes to St George’s Chapel and demands a feast. The overworked Lord Privy Seal is late to the banquet, where the jester Patch is the lord of misrule. Master Sexton warns him that ‘the pilgrims will crumb you’ and advises: ‘Keep walking. Trot on till you get to Putney.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Henry VIII • Thomas Wriothesley • Robert Aske • Richard Riche • Gregory • Eliza Tudor • Lady Mary • Margaret Vernon • Mercy • Jane Seymour • Jane Rochford • Rafe • Nan Seymour • Richard Cromwell • Christophe • Sexton

This week’s theme: Cromwell’s two bodies

Once the king leaves his inner rooms and enters his privy chamber, his natural body unites to his body politic: here he is dressed and presented to the world, a bulky, new-barbered man scented with rose oil. As rebels run free in the north, and the members break faith with the head, a kind of mutiny or civil war has broken out in the king's body.

The Pilgrimage of Grace provides Hilary Mantel with a narrative problem. It is the greatest rebellion against the Tudors, a popular uprising across the north, and we, Cromwell, don’t see any of it. ‘He could go north himself,’ he thinks. He knows the roads; he rode them for the cardinal. But these days, his person – his body – is too valuable to risk with rebels. So, he stays with the king and the king’s body.

Stuck behind Cromwell’s inner eye, we see the rebellion from a distance. ‘All information that comes in, if it is fresh, is wrong: if it is stale, it is possibly accurate, but also useless.’ Meanwhile, versions of himself get stranger ‘the further he travels from London’: he is a swindler, a renegade Jew, a magus, a child-eating ghoul. Cromwell’s shapeshifting body is compared to ‘a calf with two heads’, which rumour twists ‘from abortion to Antichrist’ in half a day.

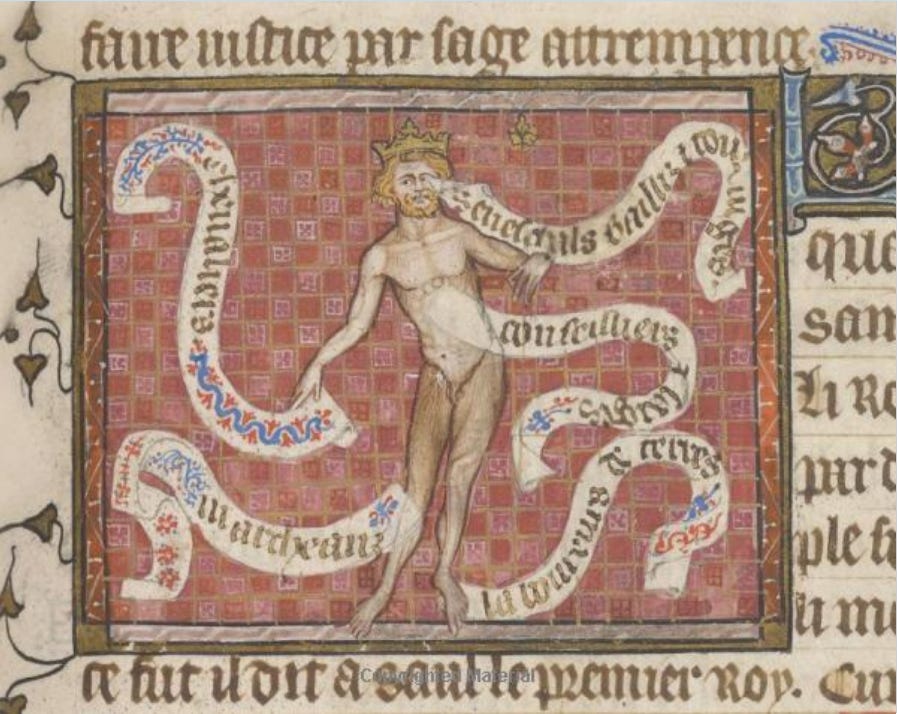

In this chapter, Mantel uses the medieval concept of the king’s two bodies1 and applies it to our Lord Privy Seal. This is the idea that Henry is divided between his corporeal ‘body natural’ – increasingly obese, sick and afflicted by bad dreams – and his ‘body politic’, the good government of his realm.

There are those who believe – and perhaps the king is one of them – that the health of the land depends on the health of its prince, and on his beauty besides. If you speak of an ordinary man you might say, ‘He cannot help his face.’ But a king must learn to help it. If he is ugly, so is the commonwealth. If the king is sick, so is his realm.

Queen Jane lets us know that Henry is once again haunted by dreams of his dead brother Arthur.2 ‘He thinks he killed him.’ Henry doubts his own legitimacy; he fears he is a usurper like Richard III. According to the Tudor version of history, Richard was a hunchback with a broken body who stole his brother’s kingdom and killed his nephews. He ended in blood and battle in the field where the Tudors’ reign began.

‘England is collapsing in on herself, like a house of straw.’ The body of England is rotting as ‘the most deft of the esquires cleans and re-bandages the sore leg’ of the king’s body natural. The doctors implore Cromwell to persuade Henry to watch his waistline. The rebels call for the king’s council to be bled of ‘vile blood’, by which they mean us, Thomas Cromwell: mushroom man.

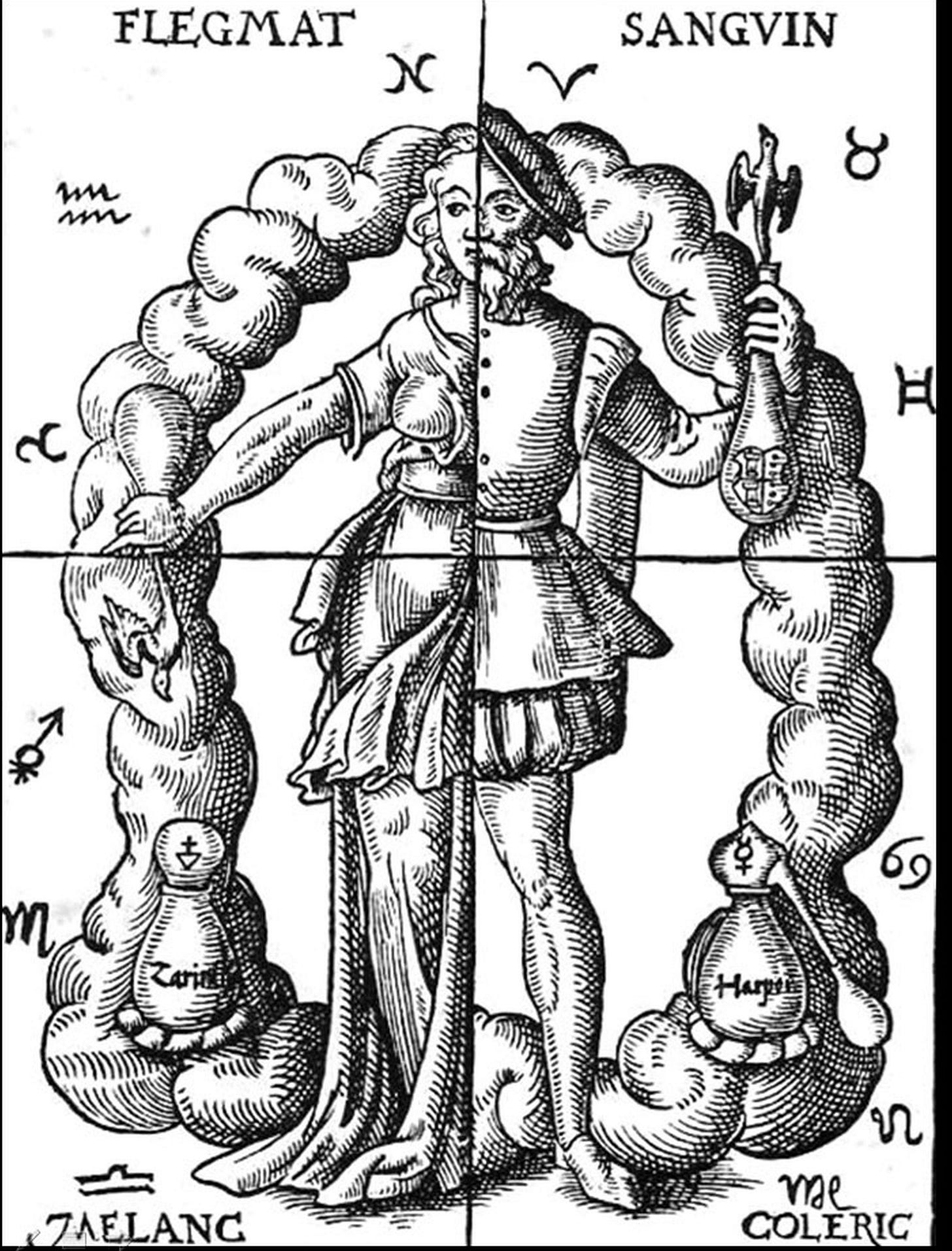

Cromwell’s body also suffers. Always on the road between Windsor and London, ‘he might as well be with the armies, so uneasy his bed, so spare his diet.’ The cold and wet have upset his balance of humours. Always in movement but far from the action, he feels ‘this frustration, this constraint’, which takes him back into his memories. ‘His dreams are oppressive’ and ‘his flesh’ has dissolved into an infinite sea where ‘his stories merge, all memories flatten to one.’

The memory is of his body being beaten by brigands who want ‘him to go through a window for them’, like Oliver Twist for Bill Sykes. He says no, ‘because I fear God’s punishment’. The thief Edwin calls his knuckles ‘a gift from me’ to learn the precept Cromwell’s father, Walter, lives by: might makes right, which is anything you can get away with.

The memory gives him two reasons for running from Putney: material and spiritual. Like a two-headed Cromwell. Stay and live your life as a labourer working for Walter; or learn a trade and leave to find a better justice than Walter’s boot and Edwin’s fist. Beyond Putney, Cromwell’s body and soul have better prospects. Beyond Putney, there are ladders.

He remembers his body broken in Florence, in the game called calcio. ‘At calcio, nobody ever declared war. The result was wreckage, all the same.’ He swears he’s not going back to Putney, whatever Patch says. He’s run to fat, but ‘he does not take his belly, as the king does, as an insult to God’s design.’ He’s content now to be ‘coddled by clerks’. Like the cardinal, his belly is a badge of magnificence.

But if the Pilgrims get hold of him, the law of Putney will rule again. ‘They will crumb you,’ warns Sexton, ‘till you are crumbed back to flour.’ And then, perhaps, Walter will have been correct all along: ‘right is what you can get away with, and wrong is what they whip you for.’

Footnotes

1. Rogues’ Gallery

Following the failed Lincolnshire uprising in the east of England, a widespread and popular revolt spread across the north. The rebels had diverse grievances, but chief among them were Henry’s break with Rome and the dissolution of the monasteries. Like previous revolts, anger was directed not at the king but at his councillors, specifically Richard Riche, Thomas Cranmer, and Thomas Cromwell.

Interestingly, Robert Aske provides a mirror to Thomas Cromwell: they are both lawyers of Gray’s Inn, and they are both masters of presentation. Cromwell uses the oath of supremacy to bind Henry’s subjects to his religious reforms. Aske makes his own ‘oath of the honourable men’ to turn a riot into something more respectable: ‘a Pilgrimage of Grace for the Commonwealth.’

Being a lawyer, Aske cannot claim ignorance. He is aware it is a gross presumption to offer oaths in the name of the king. And he must foresee – for he must be acquainted with the chronicles – what the end will be: how rank the puddle in which he swims and will one day sink.

In this chapter, both Cromwell and Henry list rebels and disloyal subjects from England’s past. Jack Straw3 joined John Ball and Wat Tyler during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, in the reign of Richard II. As Crumb notes, ‘these rebels wrecked palaces and stormed the Tower of London,’ beheading, among others, the Archbishop of Canterbury and almost killing the future Henry IV. No wonder the singing of John Ball’s words instilled fear in our current archbishop, Thomas Cranmer: ‘God help us, for now is the time.’

In 1450, Jack Cade led a revolt from Kent into London, which led to a bloody battle between citizens and rebels on London Bridge. Walter Cromwell and the men of Putney may have expected a similar confrontation with Cornishmen in 1497, but the west country rebellion was destroyed by the king’s army at Blackheath. Those rebels targeted Henry VII’s ministers, John Morton and Reginald Bray. In this chapter, we are reminded that Cromwell gets his first big break working in Morton’s kitchens for his Uncle John. And Bray is the original ‘mushroom man’, Cromwell’s patron saint of ladders – more on him later.

John Amend-All was a pseudonym for Jack Cade. As Cromwell notes, none of these rebels ‘went by their right names.’ Your name is your bond, and our lord of Norfolk would tell us that men without names ‘have no honour.’ But Henry Tudor remembers rogues among the great houses. Norfolk’s grandfather fought on the losing side at Bosworth in 1485; ‘he fought against my father!’ says Henry, teaching Richard Riche a lesson.4 He, Cromwell, suspects the current Howard of sympathising with the papist rebellion – which is why Uncle Norfolk is so eager to be seen crushing it.

Henry depends now on the northern families to put down the Pilgrimage, among them the Earl of Derby, Edward Stanley. ‘All Stanleys are turncoats,’ says Henry. ‘They will watch to see which way the battle goes before they join in.’ Edward’s ancestors had held back at Bosworth before finally siding with Henry Tudor. Richard III had the earl’s son hostage, to which William Stanley had reputedly said: ‘Sir, I have other sons.’

2. Educating Eliza

She is still a bastard, of course. But even a bastard daughter has value on the marriage market, if the King of England acknowledges her: so her education should be that of a princess.

Recall from Wolf Hall how Thomas More blazed a trail by having his daughters educated in Latin and Greek. Anne Cromwell asked her father, ‘Why should Thomas More’s daughter have the pre-eminence?’ She began to study Greek. Cromwell and More believe in the virtue of classical education for women as well as for men. Note Cromwell’s astonishment on discovering that Jane’s sister Bess knows Latin. We can see our Lord Privy Seal mentally revaluing the widow Oughtred as a potential marriage prospect.

In this chapter, Cromwell is seen making arrangements for two female tutors: Margaret Vernon for Gergory and Cat Champernowne for Lady Eliza. Champernowne was highly educated and directed the future queen’s acquisition of mathematics, geography, history, astronomy, French, Italian, Flemish and Spanish. Kat married John Ashley, who had Cromwell’s old job at the Jewel House. She became First Lady of the Bedchamber, and died in 1565, the sincerely missed friend of Queen Elizabeth I.

Cromwell ‘trusts Eliza will live to thank him.’ Mantel layers irony upon irony. Elizabeth will outlive Cromwell by over sixty years, but she is unlikely to credit her mother’s murderer with much. However, while Eliza may never thank him, England has reason to be a little grateful of Thomas Cromwell. Back in Wolf Hall, he prayed for ‘this child, his half-formed heart’ from which he hoped to ‘build my own prince.’ If he had lived to see her, Cromwell would surely have been impressed with the result.

‘Let me not be forgotten’, wrote Margaret Vernon to Thomas Cromwell in 1528. There are 21 surviving letters from the prioress Margaret Vernon to Cromwell. None of his letters survive. As he says, ‘No one should think he hates nuns, or monks either.’ Indeed, his friendly relations with Margaret Vernon cause his mother-in-law to raise an eyebrow. But we are used to the widower Cromwell’s romantic misadventures by now. We will meet Margaret Vernon later in our story.

Further reading:

3. The Power of Stones

‘Where is the Mirror of Naples?’

The magical properties of stones are invoked in this chapter. Queen Jane tells Cromwell that ‘agates are helpful’ in aiding conception and pregnancy. Agates are colourful quartz that have been used in ornaments for thousands of years. Jane's dabbling in crystal magic reminds us of Anne Boleyn’s dietary regimes for conceiving a boy. The soul-crushing pressure on both these women to be ‘fruitful’ (Henry’s word) must have been suffocating.

Meanwhile, when York falls, Henry feels emasculated. Looking down on his ancestors in St George’s Chapel, the current king must feel their judgement. No male heirs and a kingdom falling apart. He calls for the Mirror of Naples, a magnificent jewel consisting of an enormous pearl dangling from a fat table-cut diamond.

The Mirror was a bridal gift from Louis XII to Henry’s sister, Mary Tudor. The elderly king of France died a few months later, after which Mary married a big beardy man called Charles Brandon. Henry was furious with the match, and to soften her brother’s anger, Mary sent him the Mirror of Naples. Francis I insisted it was part of the Crown Jewels of France and demanded its return.

‘Tell François my claim to that country is stronger than his. One day I shall ask for more than jewels.’

England had fought for that claim during the Hundred Years’ War. In his library, the king considers the ‘mirrors for princes’, the manuscripts that Henry V brought back from France. He, Henry Tudor, sees his reflection in those mirrors and in ‘Great Harry’ and finds himself lacking.

Far below them – in the mirror of time you can see them – the Garter knights weep in their stalls, their dead skulls rattling inside feathered helms.

Cromwell considers Reginald Bray, who built this chapel and fought rebels too, and for a moment considers himself a poor copy of yesterday’s man. It is a delicate time: queen, king and minister seem insufficient to the moment. For now at least, it is one-eyed Robert Aske who rules all.

Further reading:

4. St George’s Chapel

The chapel at Windsor Castle is hallowed ground. Edward III commissioned the chapel as part of the mythmaking that replaced Edward the Confessor with the warlike Saint George as the patron saint of England.

The building had been enlarged under the supervision of Reginald Bray during the reign of Henry VII. He left his mark in some 175 examples of his rebus5 in the stone, metal and glass. And he is buried there. Henry VIII and Jane Seymour will be interred in the chapel too. In contrast, Cromwell’s remains will rest at the Chapel Royal at the Tower, alongside fellow traitors, his victims, Anne Boleyn and Thomas More.

Mantel throws in another body: John Schorne, ‘a priest who conjured the devil into a boot.’ The miracle worker’s remains had been moved from North Marston to the chapel in 1478. Cromwell clearly thinks this conjurer doesn’t deserve his place.

And another king will be buried here. In 1649, after being refused a burial at Westminister Abbey, the head and body of Charles I were conveyed to Windsor and interred beside Henry VIII and Jane Seymour. Fifty-nine commissioners had signed the king’s death warrant. One of them was a kinsman of our Lord Privy Seal, an East Anglian gentleman called Oliver Cromwell.

Quote of the week: A pity he is not made of glass

We are Thomas Cromwell. Mushroom men. ‘Grown up overnight,’ the king means. ‘Being humble-born, they have no interests of their own – only solicitous to serve their master, from whom they derive all their fortune.’

Of course, Cromwell does have his own interests. And he and the cardinal made him more than Henry Tudor. If Henry is not deluding himself, he is issuing his minister with a warning: don’t overreach yourself, Crumb. When Mantel writes of the king’s two bodies, how his corporeal self is entwined with the fate of the realm, she is also telling us that Cromwell’s life – our life – depends entirely on the capricious nature of this mutinous, disintegrating royal body. Only Mantel can make us terrified of pisspots and what they may contain:

The poor labourer owns his sleep and his stool, and can sell his piss to the fuller, whereas the king's piss and stool is the property of all England, and every fantasy that disturbs his night hours is recorded somewhere in a book of dreams, which is written in the clouds massing over the fields and forests of his realm: every stir of lust, every frightful waking. Should he be costive, he is ordered a potion; should his bowel be loose, its product is taken away in a bowl under an embroidered cloth. They can only judge what is within him, by what comes out: a pity he is not made of glass.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the second half of ‘Vile Blood, London, Autumn–Winter 1536’ This runs from page 356 to 395 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Bess Darrell is a flitting presence by candlelight.’ It ends: ‘Try and keep cheerful.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

The concept was first named in this manner by Ernst Kantorowicz in his 1957 book, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology.

The king’s dreams of Authur are the main subject of the Wolf Hall chapter, The Dead Complain of Their Burial.

Jack Straw’s legacy includes a late sixteenth-century play about his exploits, a pub named after him near Hampstead Heath (reputedly the highest pub in London), and the former Labour Party government minister, born John Straw, who adopted the rebel’s name as his own.

‘A king is made by God, not Parliament.’ Henry’s lesson refers back to Richard Riche’s testimony against Thomas More, where he claimed to have asked More: ‘Suppose Parliament were to pass an act saying that I, Richard Riche, should be king?’ William Fitzwilliam alluded to this conversation in the previous chapter when he says Riche is a witness to the king proclaiming Cromwell king. Richard Riche is a notoriously poor witness.

A rebus is a puzzle that represents words with images. Reginald Bray’s rebus incorporated a hemp-bray, an implement used to process hemp cloth.

Your identifying Cromwell’s life with OUR life relying on the king really hit home—it helps explain why I’m still rooting for Cromwell so instinctively even though he’s done some quite questionable things by now. Mantel has fused us with his personhood so effectively.

I was also agape when Henry uses the nickname Call-me! That was a funny moment. I also liked the passage when Riche says the wrong thing about where a king derives his powers and the others try to minimize the damage.

Simon, I like how Mantel handles the close third person of Crumb in the context of the rebellion. We're as uncertain as he is.