Welcome to Wolf Crawl!

Welcome to Wolf Crawl, a year-long reading of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. You can find everything you need for the read-along here, including a reading schedule and a list of characters. Every Monday, I send out a discussion post for that week’s reading. This is the first of those, looking at the first two chapters of Wolf Hall. Each post includes a summary of the plot, links to character profiles, and areas of interest and discussion. Paid subscribers receive a bonus post: The Haunting of Wolf Hall.

To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for the Cromwell Trilogy.

This week’s story

We meet Thomas Cromwell as a 15-year-old boy in Putney in 1500. His father, Walter Cromwell, has beaten him almost to death. He resolves to leave home and become a soldier abroad. His sister Kat and her husband Morgan Williams give him money for the journey. He goes to the port of Dover, where he makes money with the “three card trick” and befriends three brothers from the Low Countries, across the Narrow Sea.

We fast-forward to the year 1527. We are at York Place, the London residence of the Archbishop of York, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Cromwell is now over forty and Wolsey’s “man of business”. He has just returned from Yorkshire, where he and his master Wolsey are much despised for Wolsey’s plan to close some thirty monastic institutions. But Wolsey’s mind is preoccupied by the king’s “great matter”: the divorce of Henry’s first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon.

This week’s characters

In order of appearance:

Walter Cromwell • Thomas Cromwell • Kat Williams • Morgan Williams • Stephen Gardiner • Thomas Wolsey • Thomas More • Katherine of Aragon • Henry VIII • Anselma • Liz Cromwell • Thomas Winter • Dorothea • Pope Clement • Emperor Charles • Henry VII • Arthur Tudor • Thomas Howard • Rafe Sadler

Poll: How many readers are joining us?

I currently have no idea! So let’s find out a little bit more about this group.

Focus: The Putney cobbles

‘So now get up.’

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned towards the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

In these updates, I will not make a habit of spoiling the plot. But one detail must be disclosed from the start. On 28 July 1540, an executioner at Tower Hill will remove Cromwell’s head and end his life. We read these books knowing where we are heading. We also know that Thomas Cromwell will one day be the most powerful man in England besides the king.

But this is where we start: felled, dazed, silent. A blacksmith’s boy on the floor. As low as we can go. Head turned to the gate, awaiting a last-minute stay of execution. “One blow” now separates him from the land of the dead.

How do you feel about spoilers in historical fiction?

Theme: Stitching the Story

The story of Wolf Hall is written in three places: bodies, texts and textiles. I will highlight these three themes in these weekly posts. And today, I would like you to notice the threads:

…if he squints sideways, with his right eye he can see that the stitching of his father’s boot is unravelling.

This is the first stitch of the story. Throughout these books, Cromwell’s eye will be drawn to many threads, embroidery and lacework, the measure of cloth and the depth of a tapestry. Pay attention to this stitching: it tells a tale. In chapter two, Paternity, Cromwell looks into Wolsey’s tapestry and sees his own past. Queen Sheba reminds him of Anselma, a woman he knew in Antwerp. A woman he could have married and written a different story with different children and a different Cromwell.

As we go along, our resident stitching expert

will be on hand to expand, embellish and embroider this very tactile aspect of Mantel’s writing. She has been reimagining the Cromwell books on cloth, and I will share some of her work in these posts.

NB: This is a long post and may be clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Bonus: The Haunting of Wolf Hall

For paying subscribers, here is the first instalment on the magic and malevolent mayhem in Mantel’s writing:

Mantel's Magic

This is a bonus post for paid subscribers to accompany this weekly discussion post of the Cromwell trilogy by Hilary Mantel. Wolf Hall is a ghost story. We don’t often talk about this. We are too taken up by the intrigue of the Tudor court and the barbed conversation in candlelit halls. Mantel’s books get shelved as historical fiction, where they twitch uneasily beside bodice and hose, ruff and rapier.

Language: He, Cromwell

Mantel’s writing style is probably the main challenge for a new reader of Wolf Hall. She adopts a very unusual narrative voice. But once you get the hang of it, you’ll realise how essential it is to the magic of her writing. Unless otherwise specified, “he” refers to Cromwell. The entire story is told from his point of view, and we know nothing that he does not see. As readers, we sit perilously close to his eye-line. We are him, and yet we are not him.

This voice switches between first, second and third-person. Cromwell is “I”, “you”, and “him” as our consciousness becomes enmeshed with his.

Take, for example, this paragraph:

Stephen sings always on one note. Your reprobate father. Your low birth. Stephen is supposedly some sort of semi-royal by-blow: brought up for payment, discreetly, as their own, by discreet people in a small town. They are wool-trade people, whom Master Stephen resents and wishes to forget; and since he himself knows everybody in the wool trade, he knows too much about his past for Stephen’s comfort. The poor orphan boy! [emphasis added]

This is about Cromwell’s nemesis, Stephen Gardiner. But that “your low birth” is directed at Cromwell and, by proximity, at us. “He himself” is Cromwell. And “the poor orphan boy!” is his own sly thought directed back at Stephen.

If you are having trouble getting used to this style, I recommend the audiobooks. Hearing the language can really help. Either way, once you are accustomed to this narrative voice, you’ll have little problem working out who “he” is, from one sentence to the next.

Why do you think Mantel writes Cromwell’s point of view in this way?

Theme: Fathers and Sons

This is a story about fathers and sons. Literal and figurative. Having fled Walter Cromwell, Thomas is a son without a father. The King of England is a father without a son. As Cromwell’s patron, Wolsey becomes a father figure to the talented and resourceful lawyer, rising in the world. Cromwell has his own son, Gregory. But he also takes many young men under his wing. We have just met one: Rafe Sadler.

Another theme that runs through these books is how women fight for space in this patriarchal society that grants them few rights and little protection:

‘I don’t see why he takes Leviticus to heart. He has a daughter living.’

'But I think it is generally understood, in the Scriptures, that “children” means “son”.’

Character focus: Cardinal Wolsey

All the characters in this trilogy were real people, with a few exceptions that we will encounter later. So at each turn, you may be tempted to scurry away and read more about this colourful cast. You should do so. Many of these people deserve to be the focus of their own story, and there is a near-inexhaustible mountain of fiction and nonfiction to read on Thomas More, Wolsey, Henry, Queen Anne and the rest.

At the same time, when we read Wolf Hall, we do well to remember that we are reading a work of fiction. We are interested in the real people who inspired these characters. But ultimately, these are Mantel’s creations. Mantel’s Cromwell, Mantel’s Thomas More. And Mantel’s Cardinal Wolsey.

“I needed to know Wolsey to understand Cromwell”, wrote Mantel. We know him mostly through the eyes of his enemies. A “butcher’s boy” who dared to eclipse the King of England in his ostentatious displays of wealth and power. By 1515, this lowborn prodigy of Magdalen College, Oxford, was a cardinal, archbishop and Lord High Chancellor of England. His lavish residences at Hampton Court and York Place rivalled the king’s own palaces.

This is how we see Wolsey, Mantel wrote: the “great scarlet beast” of an “old world”. Her way to the man leads through his first biographer, Wolsey’s own servant George Cavendish. A character we will meet next week. His book, Thomas Wolsey, Late Cardinall, his Lyffe and Deathe, paints a sympathetic portrait of a loyal councillor who released the young King Henry from the burden of governance. A renaissance man with a love of humanist literature, art and architecture.

Mantel’s Wolsey is Cromwell’s mentor. He explains to Cromwell how things really work at the centre of power. And how these things came to be. He is a kindly father figure and a magnificent host. But he has one particular failing: an impatient lack of interest in detail and practicalities:

When he once, as a test, explained to the cardinal just a minor point of the land law concerning – well, never mind, it was a minor point – he saw the cardinal break into a sweat and say, Thomas, what can I give you, to persuade you never to mention this to me again? Find a way, just do it, he would say when obstacles were raised; and when he heard of some small person obstructing his grand design, he would say, Thomas, give them some money to make them go away.

In this regard, Cromwell will outshine his master. Cromwell’s patience is frightening. His grasp of detail, alarming. Wolsey has put him in charge of what the historian Diarmaid MacCulloch calls Wolsey’s “legacy project”: finding money for his two colleges and princely mausoleum. Cromwell turns out to be very good at finding money and getting things done.

Quote of the Week

Each week, I’ll pick out a favourite quote and talk about it. This week, I have two I would like to share:

He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury. He will quote you a nice point in the old authors, from Plato to Plautus and back again. He knows new poetry, and can say it in Italian. He works all hours, first up and last to bed. He makes money and he spends it. He will take a bet on anything.

The boy of fifteen was good at “heavy work” and could “add”. Brains and brawn. But, there is a quarter-century between chapters one and two. It is a lifetime. Where has Cromwell been, and what has he done? For he is now a man of many languages and many talents. There are clues in this chapter: a woman in Antwerp, and shadowy memories of the holy city of Rome:

‘You don’t understand Rome.’

Wolsey can’t contradict him. He has never felt the chill at the nape of the neck that makes you look over your shoulder when, passing from the Tiber’s golden light, you move into some great bloc of shadow. By some fallen column, by some chaste ruin, the thieves of integrity wait, some bishop’s whore, some nephew-of-a-nephew, some monied seducer with furred breath; he feels sometimes, fortunate to have escaped that city with his soul intact.

We also learn that he fought as a mercenary in the French army. But in truth, we know very little about the real Cromwell’s years abroad. And it is this gap in the historical record that Mantel exploits so brilliantly in Wolf Hall.

At the end of the first week, what do you think of Thomas Cromwell? What sort of man is he? And would you care to meet him on a dark night in Rome?

Use the comments section to discuss any thoughts, feelings or ideas arising from this week’s reading, whether erudite or silly. All contributions welcome!

That’s all from me this week. If you found this post useful and have the means to do so, I encourage you to become a paying subscriber, if you haven’t already. This supports the book group and keeps the Duke of Norfolk from my door.

Until next week, I am your faithful servant,

Master Haisell

Cromwell Trilogy

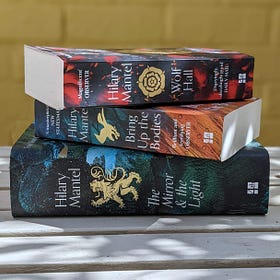

Welcome to the main page for the 2024 slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy: Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies, and The Mirror and the Light. Bookmark this page for reference. It will be regularly updated with everything you need, including the reading schedule, resources, character profiles, links to weekly updates, discussion and more.

What a great way to start my 2024 reading year!

I believe Mantel uses the "he" technique as a compromise between first person and close third. It's as close as we can get without the constraints of a narration.

And it allows her the flexibility to occasionally give us the POV of a third person as well, even if that POV is implicitly filtered through TC's mind.

The entire first chapter is a study of Tom's character assets, so artfully told. As in, of course he's picked up the Welsh language.

Here's what stood out to me in the text. Tom is trying to figure out how to make money to flee his father and considers helping people load their carts. Page 12.

"Men trying to walk straight ahead through a narrow gateway with a wide wooden chest. A simple rotation of the object solves many problems."

It's that ability to see a problem from a different angle that TC will use again and again.

This feels like the most daunting aspect of 'joining in'. My word, your readers are a very bright lot indeed.

I'm a simple soul coming at 'Wolf Hall' for the first time. On the evidence of the first two chapters, I'll be finding it hard to stay slow. It feels pretty compelling. All the nervousness I had about language, characters and complexity has dissipated. I feel a bit self-conscious that this is the level of my insight but, hey, here goes ... I like the story, and the words. The details are everything (I wouldn't spot hidden meanings if they jumped up and slapped me with a Cardinal's chamberpot) ... the visceral, raw, blood-soaked start had me gripped ... the mystery of the intervening years locked me in, and the intrigues of the Court are already playing out. It's a keeper; I shall try and keep myself from reading ahead. I am in awe of the clever folk in the comments!