📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 46 of Wolf Crawl

This week we are reading the first half of ‘Ascension Day, Spring–Summer 1539’. This runs from page 629 to 651 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “Call-Me wants a picture of the king” It ends: “When you look at him these days you think of Jupiter, planet of increase.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

A cold winter. Dispatches from Call-Me in Brussels, holding out hope for Christina’s hand for England. Wyatt in Spain. ‘I am at the wall. I cannot endure till March.’ England excommunicated, France and Spain beat war drums and no Englishman abroad is safe. Home is now ‘more like a castle than a realm.’

Norfolk rides north, condescending to Cromwell to drop the formalities. But he, Milord Cromwell, pictures himself with Thomas Howard’s sword sunk into his heart. The king’s leg is bad and so is his. ‘Decrepit,’ he tells his nephew. ‘Lord Cromwell in his Later Years.’

He questions Gertrude in the Tower and coaxes the cardinal to speak from whatever lofty place he now resides. Wolsey will not be tempted, though his servant grows desperate. Cromwell intends to secure a German alliance and a German bride, with alum added to strengthen his case.

The ambassadors are recalled. Eustace Chapuys bids farewell and Call-Me returns to warm embraces, his feet muddy from the road, his cap’s feather catching fire in Cromwell’s candle.

Wriothesley gets to work on Wyatt’s letters, as Cromwell keeps an eye on Gardiner. He, the king’s Secretary, plans a new order of precedence, putting secretaries of state above lords of ancient and noble blood. He, the king’s Vicegerant, looks down on little bishop Gardiner, and eyeballs Norfolk, with his sword.

He watches the king’s daughter for any sign of treason. She says she does not ‘let anybody tell her anything.’ His own daughter, an avowed heretic, writes from Antwerp and asks to be received in England. ‘If she comes she will be in danger, and a source of danger.’ We are England at Easter, 1539.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Rafe Sadler • Henry VIII • Edward Tudor • Thomas Wriothesley • Thomas Howard • Stephen Gardiner • Castillon • John Husee • Chapuys • Richard Cromwell • Christophe • Gertrude • Mathew • Lady Rochford • Richard Riche • Hans Holbein • Lady Mary • Jenneke

This week’s theme: Ascension

Christophe says, ‘If all your offices were counted, you should have a ladder on a chair, and a ladder on that, and a throne perched up in the clouds, to look down on Norferk and the foes, and spit on them.’

This week culminates in Cromwell’s plan to ascend to the heavens. The Feast of the Ascension usually takes place in May, marking the end of the forty days when Christians believe the resurrected Christ appeared to his followers before ascending into Heaven.

In 1539, England is going the other way – or so thinks half of Europe. Henry is ‘a man doomed to Hell’; excommunicated. ‘Who can deal with an excommunicate king?’ The mood is martial. Ambassadors are recalled. ‘… no formal declaration of hostilities. But it feels like war.’

And while everyone is looking out to sea for Spanish ships, he, Lord Cromwell, has drawn up a measure for the new Parliament. It’s rather innocently called the ‘Act for the Placing of the Lords in the Parliament.’ Diarmaid MacCulloch describes it as:

a major shake-up in the order of precedence for the most powerful men in the realm, a matter of huge importance when political realities were expressed through public ceremony and formal rankings in seating and processions.

Now, if you have a government job, you outrank everyone else, regardless of your family name and ancient title. The butcher’s dog and blacksmith’s boy may be the lowliest of barons, but as Chief Secretary to the King, he now sits above all barons. As Vice-Gerant, he looks down on all bishops. Hello, Stephen. As Lord Privy Seal, he towers above almost all dukes. Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, is also Lord Treasurer, so he keeps his seat. But make no mistake: this is a revolution in government.

This is Cromwell’s Ascension.

This week, we leave Cromwell in a position of immense power. His son will sit in the new Parliament, ‘a tractable one’ that will do the king’s and his bidding. ‘Henry and Cromwell. Cromwell and Henry.’ He is inching closer to obtaining the king a bride from Cleves, securing both the dynasty and the new religion in England. Everything is going to plan.

All he must do now is make sure nothing calls him away. He thinks, ‘I don’t want to find that, in my absence, the king has panicked and called Norfolk back from the borders, or put a plaice in my seat at the council board.’ A plaice? That’s fishy Gardiner, ‘with his mouth turned down and his underlip thrust out.’

Because no one hates Cromwell’s ascension more than Stephen. ‘Going out, as he’s coming in.’ ‘Coming in as he’s going out.’ They’ve hated each other since Wolsey’s day.1 But as he says to Gertrude Courtenay, ‘Old enemies bring each other down.’

Footnotes

1. Six Wives and Four Eyes

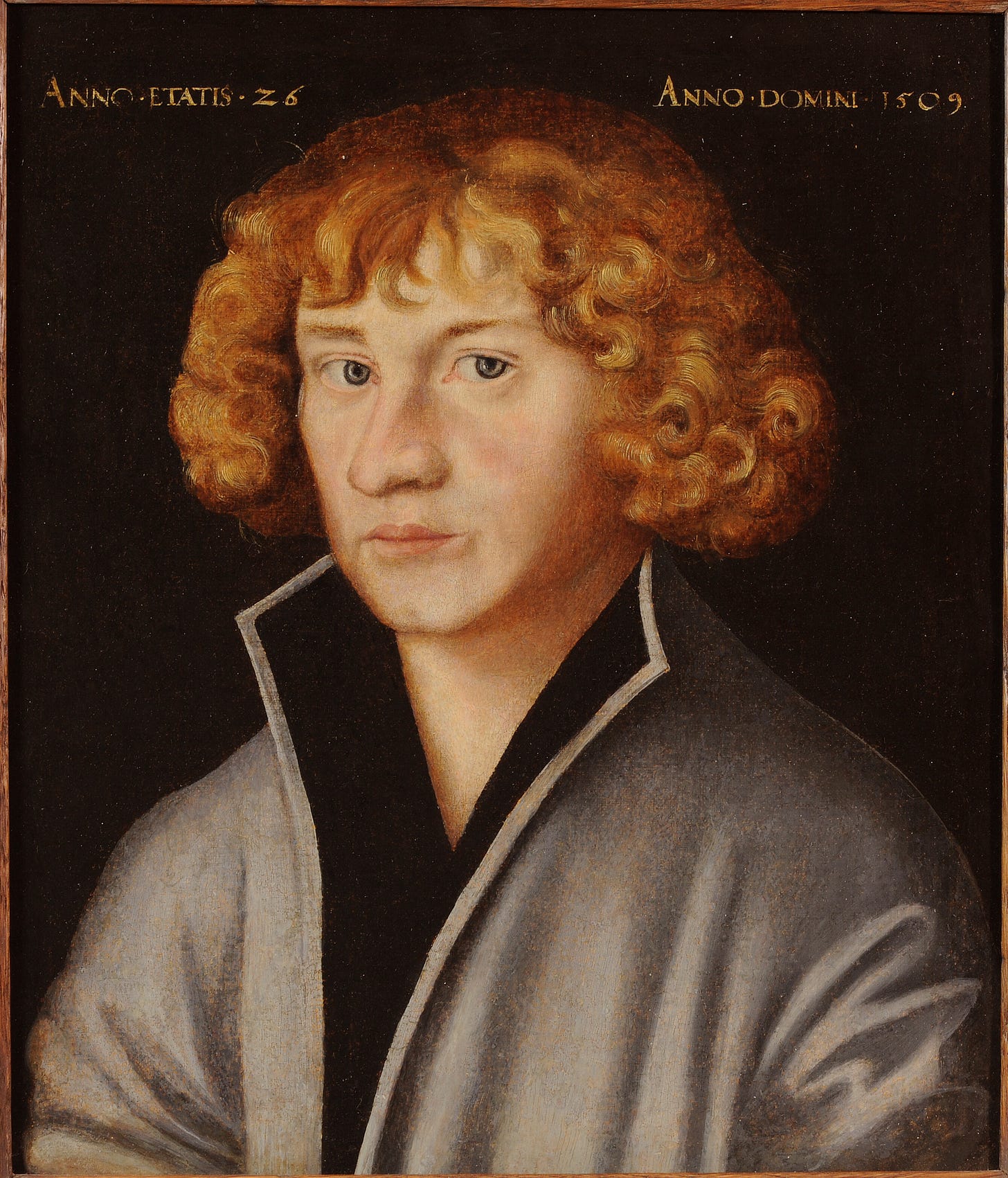

Henry owns more than a hundred looking-glasses. If they had a memory, we could send one that reflected the prince as he was at Christina’s age: tumbling curls, broad shoulders, damask skin.

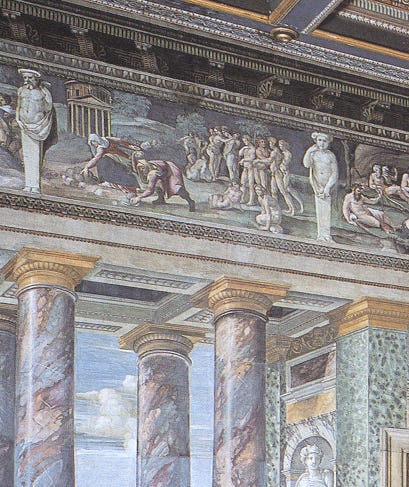

You may remember Cromwell reaching for his reading glasses in Bring Up the Bodies. Glasses first appeared in Italy in the thirteenth century and the glassworks at Murano in Venice became an important centre of manufacture. As you can see in the painting above, these glasses did not have arms and were either handheld or rested on the bridge of the nose.

Henry did indeed have a spectacular collection of spectacles. We know this from the inventory made at his death. Claire Ridgway of the Tudor Society has supplied a selective list of the royal eyewear in the link below.

Here, Mantel reprises the idea of a memory machine from Wolf Hall, and uses the king’s glasses as a means to meditate on lost youth. Both Henry and Cromwell are feeling their years.

Of course, these glasses are another mirror; but the reflected prince would be a lie, like a painting that flattered. These deceptive images are powerful. Cromwell tells Lady Rochford ‘We do not send pictures of our princesses abroad.’ But everything now rests on the picture of Anne of Cleves, which Hans Holbein has been dispatched to paint.

Further resources:

2. Fathers and sons

Never was a son so anxious to please his father, as Mr Wriothesley is to please you.

This is the third reference in recent pages to fathers and sons. Thomas Cranmer called the king ‘fatherly’ in his treatment of John Lambert. Cromwell agreed, thinking of his body burning in Walter’s forge. Cromwell told Rafe, ‘We shall prosper, son.’ Sadler is his protégé, a son in all but name. Unlike Call-Me, his loyalty is never in question, but his body is ‘meagre as a boy, breakable.’

When Thomas Wriothesley is in danger behind enemy lines, we wonder what Crumb would do if it were Rafe instead, or Thomas Wyatt, who he promised to protect like his own son. Would he try to rescue them?

Richard Cromwell, another adopted son, puts the question: ‘You used to have a plan of that fortress. Would we send a troop of men to break him out?’

They glance at each other, turn away again. Probably not.

That look, and that averted gaze, tells us all we need to know.

3. Necromancy

‘Sooner or later,’ he warns the king, ‘all such men grow desperate, and then they turn to necromancy.’ I also, he thinks. I sit at my desk day after day, waiting for the cardinal to whisper in my ear.

The license to John Misseldon is recorded in the archive, 13 February 1539. He may practice his ‘science or cunning in England’ as long as he sticks to ‘plain science of philosophy’ and does not dabble in ‘necromancy’. The detail is mentioned to remind us that Cromwell is also a desperate man tempted by the dark arts.

After his death, England will bring in the first modern law against witchcraft, ‘An Act against Conjurations, Witchcrafts, Sorcery and Inchantments’ in 1541. That act made it a capital offence to harm others with magic. It was repealed in 1547 and witchcraft remained a church matter until 1562 and 1603, when successive acts gave secular authorities power to prosecute alleged witches.

In the British Isles, the last person executed for witchcraft under statute was Janet Horne in 1727. In 1735 all witchcraft laws were repealed and from then on practitioners were considered con artists and not necromancers.

Further reading:

4. Jewels for a giant

Perhaps alum is not the foundation for a love match. But members of the king's council agree: you have reason on your side, Lord Cromwell.

Fans of Dorothy Dunnett’s The House of Niccolò books can squeal with delight at the mention of alum. The plot of Niccolò Rising, Dunnett’s baroque caper through fifteenth-century Europe, hinges on the discovery of alum at Tolfa near Rome. Alum was essential for dyeing cloth. As Cromwell notes, the papal monopoly made Agostino Chigi very wealthy but it was a pain in the neck for the cloth industry of northern Europe.

Diarmaid MacCulloch notes that Cromwell had an early education in the art of evading the alum monopoly. In Italy, he worked for the Frescobaldi.

The Frescobaldi were one of Florence’s great mercentile families, involved in trade with England since the thirteenth century. When Cromwell was a boy and over the course of his time in Italy, their English business grew massively in clandestine co-operation with King Henry VII, to include a large-scale alum-smuggling industry to northern Europe via England: they imported this vital dyestuff for the cloth industry from Egypt and the Ottomans in the infidel eastern Mediterranean.

Henry VII paid lip service to the papal monopoly and then ignored it, to the credit of England’s finances. For the young Thomas Cromwell, it must have been an invaluable education in the interplay of trade, power and religion.

5. Solace and Consolation

He takes papers out of his bag, and a package. Henry's eyes light on it. 'What have you brought me?' It is a work called The Solace and Consolation of Princes, written by an advisor to the princes of Saxony. Henry turns it over in his hands. 'A wife would be a consolation.'

The advisor was George Spalatin, a humanist and friend of Martin Luther. The book is mentioned in a letter from John Husee to Lord Lisle, as a gift from the astronomer Nicholas Kratzer to the king. Kratzer had a cameo appearance at Austin Friars in Wolf Hall.

Cromwell puts the book in Henry’s hands. It sounds like a Mirror for Princes and I think we are meant to contrast it with Niccolò Machiavelli’s book, which Lord Morley passes to Cromwell via his daughter, Lady Jane Rochford. ‘The king has nothing to learn from Niccolò’s book,’ Cromwell thinks. It tells a king how to use fear to control his subjects.

I suppose Spalatin’s book teaches a milder form of kingship and maybe Cromwell wishes his king would read it.

6. The Judgement of Paris

'Which one will he take? They say one has brown hair and one blonde.' 'I hope I shall not be called on for the Judgement of Paris.' 'Go for the blonde, is my advice.'

Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, began a fight between Hera, Athena and Aphrodite over who was the most beautiful. Aphrodite bribed Paris of Troy to settle the argument in her favour. The bribe was a bride, Helena, the fairest mortal alive. Paris abducted her from her Greek husband and so began the Trojan War.

If Cromwell is reluctant to be Paris, Lady Rochford is more than happy to be Eris, lady-in-waiting of discord and strife. Always ready to cause trouble, she served five of Henry’s six wives, until she was undone and died with Katherine Howard at Tower Hill in 1542. Speaking of which:

7. Katherine Howard

‘By the way, the Howards sent a little lass called Katherine, to see if we would have her among the new queen’s maids. Succulent and plump, and I doubt she has passed her fifteenth year.’

Katherine is Uncle Norfolk’s niece. With her mention in this chapter, we have all six wives included in the novels: Divorced, beheaded, died. Divorced, beheaded, survived.

'Send her away.'

Cromwell’s no fool. This is what the Howards and Boleyns have always done: putting their daughters and nieces where the king can see them. Now, Crumb must work hard and fast to bring Anna across the sea, so Henry can see her. And hope to God he likes her.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the second half of ‘Ascension Day, Spring–Summer 1539’ This runs from page 651 to 682 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “One morning after Easter he wakes with a heavy, aching head, his neck stiff.” It ends: “Five days. Wolf Hall.”

If you are enjoying this slow read, please consider recommending it to others so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. You can now give your friends, or your enemies, the gift of Cromwell with an annual subscription to Footnotes and Tangents.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

These are quotes from the first lines of ‘Paternity’ in Wolf Hall and ‘Crows’ in Bring up the Bodies. Both chapters introduce Stephen Gardiner to those novels. Gardiner’s first appearance in The Mirror and the Light is in ‘Corpus Christi’ and it mirrors the first two: ‘Stephen Gardiner, sweeping in.’

"Mon cher, I do not know when I shall return. Should we by some mischance, never again…"

Chapuys' farewell is an icy wind. A small man with a big presence in these books. We will miss his suppers with Crumb.

Note: there are numerous references to poison in this chapter (this week and next). Also note that Gertrude is eating almonds.

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/06/13/732160949/how-almonds-went-from-deadly-to-delicious