Welcome to week 28 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 3, Part 2, Chapters 2–8.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus posts on all Tolstoy’s parties and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: Life’s Retreat

This is one of my favourite weeks of War and Peace. Every chapter is golden, and together, they demonstrate the great breadth of Tolstoy’s writing and the stories held within this book.

As the Russian army retreats towards Moscow, life retreats from the body of the old prince, Nikolai Bolkonsky. The book opened in medias res with chatter about Napoleon in a high society salon. Now Anna Pavlovna’s soirée is brutally bookended by the terror of a burning city under bombardment and the horror of watching a loved one die.

Each chapter offers us a different perspective on events. And with remarkable agility, Tolstoy abandons our main cast of characters, to tell the story of Alpatych at Smolensk and Lavrushka with Napoleon. These snapshots help demonstrate Tolstoy’s argument in the chapter we read last Sunday, where he wrote:

…the innumerable people who took part in the war acted in accord with their personal characteristics, habits, circusmtances, and aims. They were moved by fear or vanity, rejoiced or were indignant, reasoned, imagining that they knew what they were doing and did it of their own free will, but they all were involuntary tools of history, carrying on a work concealed from them but comprehensible to us.

With hindsight, the events appear inevitable and even deliberate. But the role of the historical novelist is to forget this and focus on those ‘innumerable’ lives being lived in that moment.

And above all these lives, the sky watches without pity: the sun, ‘a huge crimson ball in the unclouded sky’, beating down on a retreating army; at night, ‘the sickle of the new moon’ shining strangely over a burning city.

Chapter 2: The Unread Letter

After Andrei left Bald Hills, the old prince broke off relations with Mademoiselle Bourienne. Marya interprets this as done to wound her. Julie writes (in Russian) to express her patriotism, and Andrei writes to advise his father to leave Bald Hills. The old prince refuses to discuss the war and seems confused about the French position. Instead, he immerses himself in a building project.

Nikolushka • Marya • Nikolai Bolkonsky • Mademoiselle Bourienne • Dessalles • Tikhon

Nikolai Bolkonsky appears incapable of protecting his household. Who should take control instead?

Every time we return to Bald Hills, my heart is not my own. The house is permanently in the shadow of tragedy: past, present, and future. Nikolai Bolkonsky’s actions are always painfully ambiguous — even more so now that his mental faculties are failing. Why does he stop seeing Mademoiselle Bourienne? To hurt Marya? Or to belatedly follow his son’s wishes, regretting the bitter way they parted? Or a cry for help to his children from within a mind closing in on itself?

The non-reading of the letter is heart-wrenching. The old prince is confused about where they are and the war they’re in. He cannot contemplate the idea that his home might be at risk. And instead he turns to the plans for a new building. A building that is unlikely ever to be built.

Chapter 3: The Time War

Mikhail Ivanovich returns Andrei’s letter to the old prince. But Bolkonsky is busy with his will and issuing instructions to Alpatych, who will ride out to Smolensk. Later, the old prince struggles to sleep and has his bed moved to a place where he has not slept before, free from oppressive thoughts. There, he remembers the letter, reads it and briefly understands it. But the past pulls him back in search of peace.

Nikolai Bolkonsky • Mikahil Ivanovich • Alpatych

How does this chapter change how you see the old prince?

‘Leave me in peace!’

‘Oh, quicker, quicker! To get back to that time and have done with all the present! Quicker, quicker – and that they should leave me in peace!’

Some of the biggest battles in War and Peace take place inside the minds of its characters. I love this chapter for the rare glimpse we get of Nikolai Bolkonsky's thoughts. We see his happy memories of being young and healthy and at the centre of things.

Now, he's putting in an order for a bound case to hold his will. Now he's meditating ‘contemptuously at his withered yellow legs.’

‘No peace, damn them!’ He re-reads his son's letter and dimly grasps its meaning. But instead of acting on it, he turns in on his dissolving memories. We'd hardly expect him to do otherwise. So many of our characters are looking for peace. The old prince is perhaps further — and closer — from it than most.

Do we think he was ever happy and at peace?

Chapter 4: A Good Day for Harvesting

Alpatych goes to Smolensk with the prince’s instructions and a letter from Marya for the governor. The French bombardment of the city is underway. Alpatych stays with an innkeeper who beats his wife for wanting to leave the city. The governor of Smolensk tells Alpatych that the Bolkonskys should leave for Moscow immediately. Looting begins, and the innkeeper sets fire to his shop. Andrei appears and writes a note to his sister: leave for Moscow now. Berg is there to complain about the looting and for Andrei to ignore him.

How is this ‘war chapter’ different from all previous scenes of battle in the book? What do you think this might mean for the story ahead of us?

What do you make of the civilians’ response to the bombardment? What surprised you?

Wonder-worker

Smolensk is a little over 200 miles southwest of Moscow on the Dnieper River. This sacred city was home to the ancient icon Our Lady of Smolensk, which Russians believed was the same venerated icon made by Saint Luke and lost when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

Napoleon expected Russia to engage the French army outside the city walls to prevent Smolensk’s destruction. As we saw in Chapter One, nothing happened as Napoleon or Alexander intended. The army remained within the fortified city and then abandoned it to burn. The icon survived Napoleon’s invasion only to be destroyed along with most of the city during the Second World War.

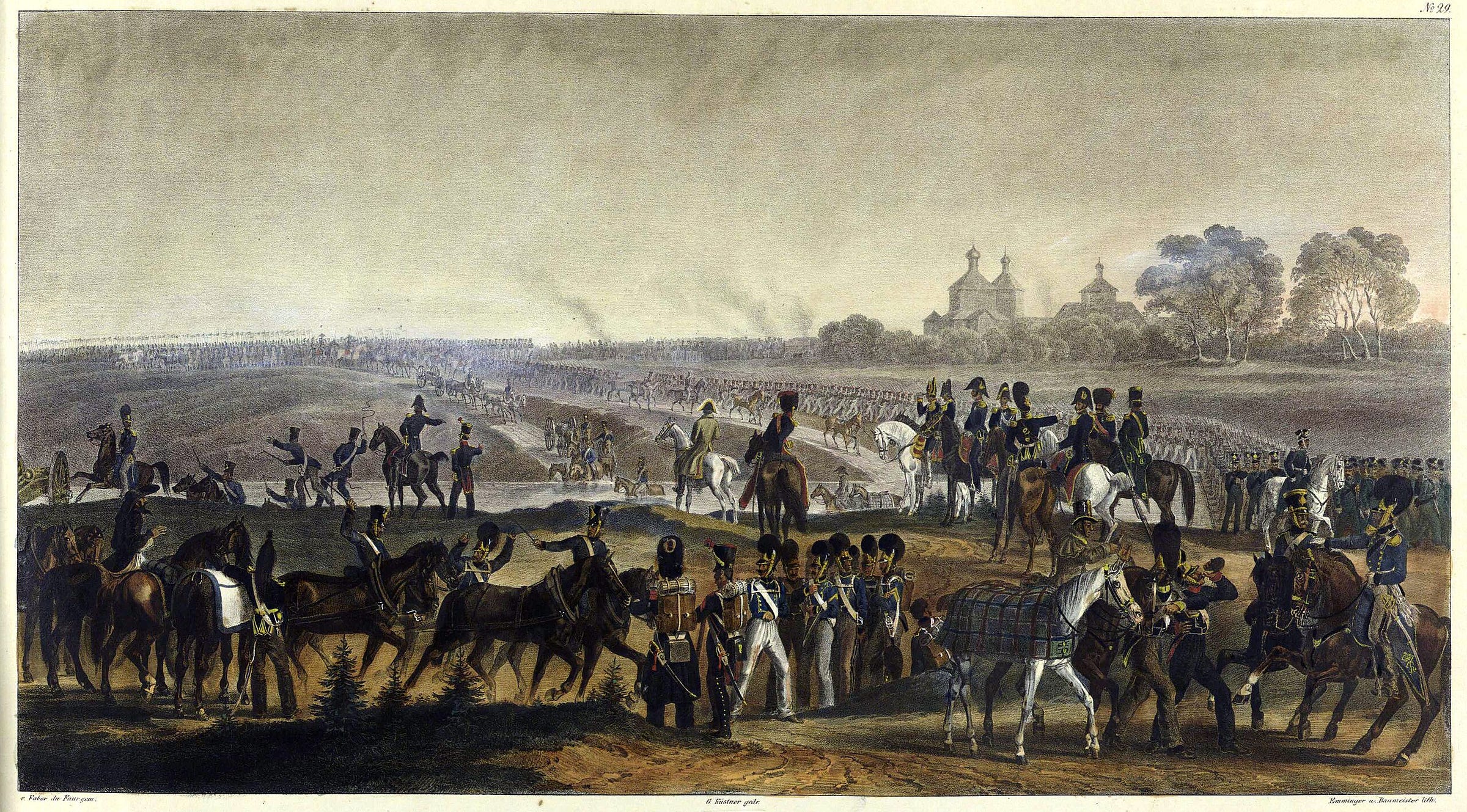

Sickle moon over Smolensk

What struck him most was the sight of a splendid field of oats in which a camp had been pitched, and which was being mown down by the soldiers evidently for fodder.

Tolstoy wants to tell us about how Smolensk was lost and how the fire began. He's got any number of fleshed-out characters to be witnesses. But no, he introduces us to Alpatych – Bolkonsky's servant of 30 years standing – and writes a short story entirely for him. It’s brilliant, full of drama and horrors and humour and humanity.

Alpatych’s sendoff lets us know the family he leaves behind (so we can worry about whether he will get back safely). But he’s no hero: see how he proudly copies Bolkonsky’s mannerisms and prejudices. He ignores the innkeeper’s brutal treatment of his wife while they ignore the danger of the French bombardment.

And the shelling is terrifying. This is one of those scenes where Tolstoy makes you care bitterly about people you've only just met – I do hope the cook is OK.

It is a long and intense chapter with so much vivid imagery: the soldiers harvesting oats for fodder before they, too, become fodder for cannons. The sickle of a strange new moon that portends rebirth, or else: the end of the world.

And finally, Berg, poor old Berg. He’s got himself a ‘very agreeable and high-profile’ position in the First Army. But I don’t care. I just hope that the cook gets safely out of Smolensk.

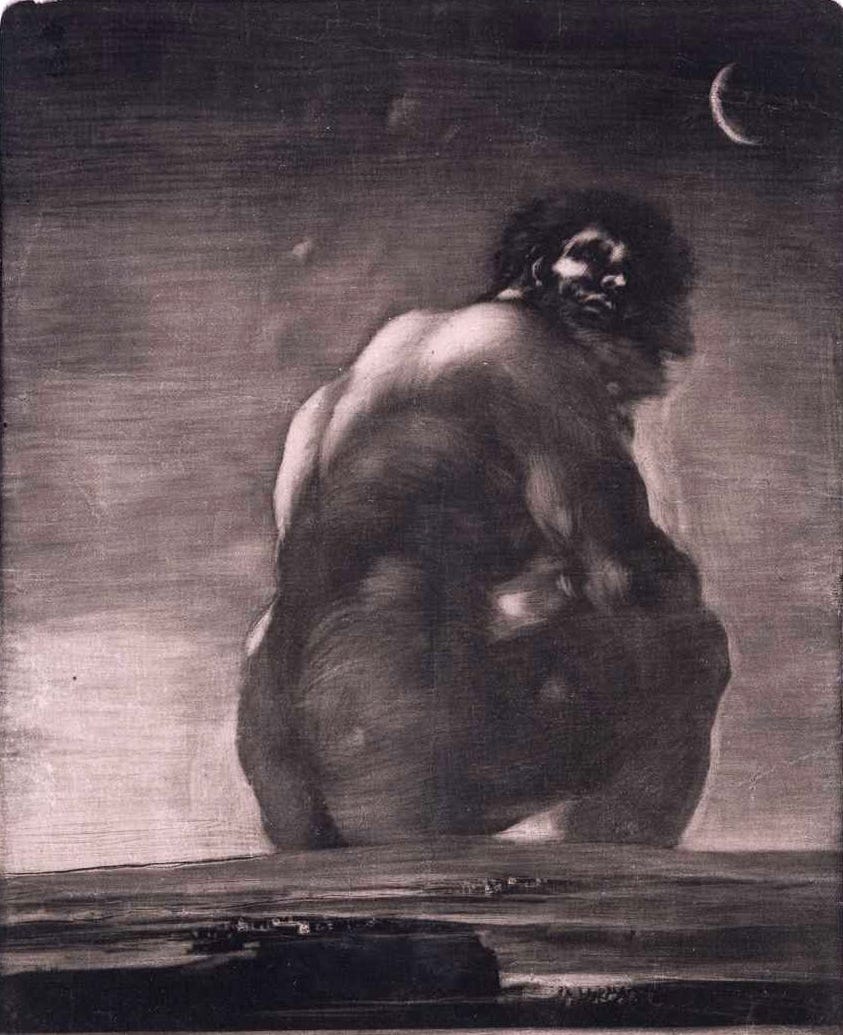

Goya’s Giant

Thank you

for suggesting this week’s main image at the top of this post. In the chat, she wrote that this chapter reminded her of Goya’s The Colossus, a giant rising like the Grim Reaper over the city of Smolensk. There’s some disagreement over whether this is actually a Goya painting. But that aside, I’ll be sharing artwork from Goya’s ‘The Disasters of War’ and his ‘Black Paintings’ as our story continues.Goya’s art captures the horrors of the Napoleonic Wars in Spain and complements Tolstoy’s writing on the war in Russia. Here, I have included another Goya painting of a giant with a sickle moon reminiscent of that strange light above Smolensk in this chapter.

Chapter 5: Green Plums

Andrei leads his regiment in retreat towards Moscow. The heat is unrelenting. On his way, he stops at Bald Hills, which has been abandoned. He talks to Alpatych and sees two girls stealing plums from the hothouse. When he returns to his regiment, the soldiers are bathing. The naked bodies fill him with horror and disgust as he realises they, and he, are cannon fodder. Bagration writes to the Minister of War demanding that the army be better led under one commander.

Andrei • Alpatych • Bagration • Timokhin

How does Andrei’s visit to Bald Hills affect him?

Andrei is running from his past. What do you think he is running towards?

A new sensation of comfort and relief came over him when, seeing these girls, he realised the existence of other human interests entirely aloof from his own and just as legitimate as those that occupied him.

What a beautiful and sad chapter. It is a melancholy tour of ransacked greenhouses and shuttered windows. Late summer, a bountiful and wasted harvest. And these poignant images of people moving in the growing shadow of a darkening day: Alpatych sobbing as he clings to Andrei's leg. An old deaf man sitting in an ornamental garden, ‘like a fly on the face of a loved one who is dead.’

And the little girls with sunburnt feet scrumping green plums and scampering across the meadow. For me, it is one of the most haunting images in the entire book; it comes back to me often, as though it were a memory of my own.

And finally, the soldiers bathing naked in a green pond: ‘Flesh, bodies, cannon fodder.’ It is one thing for the generals on high to see their men like this. But Andrei looks down at ‘his own naked body’ and sees meat for butchering. Andrei has already foreseen his own death at the hands of Anatole. Now, he sees it coming for him as he bathes alone in a deserted barn.

Chapter 6: The Land of the Blind

Meanwhile, in Petersburg, the battle of the salons continues. Bilibin joins the pro-French gaggle at Hélène’s salon. Prince Vasili flits between his daughter’s circle and Anna Pavlovna’s. He often forgets what is correct to say where. As Kutuzov’s star ascends, Vasili is forced to change his opinions overnight. The blind courtier becomes the ‘very wise man’ who will save Russia.

Prince Vasili • Anna Pavlovna • Bilibin • Kutuzov

This chapter is very similar to the opening chapters of War and Peace. Has your response to the salon chatter changed? Why?

‘A fine idea to have a blind general! He can't see anything. To play Blindman's Buff? He can't see at all.’

How jarring it is to flit from these war scenes to the sedate salons of Petersburg.

Instantly recognisable is Prince Vasili's flip-flopping over the appointment of the one-eyed Kutuzov as Commander-in-Chief. Public figures who are all form and no substance: a toe in each camp, and terribly confused about what they should say.

So the big news is that the one-eyed general has been made a prince and is now in charge of the whole army. But the worst thing you can do at these salons is point out anyone’s hypocrisy. The ‘man of great merit’ lacks the ‘courtly tact’ of Vasili and Anna Pavlovna. He says:

‘But they say he is blind, Prince?’

’Eh? Nonsense! He sees well enough.’

A chapter all about seeing one thing and saying another.

Chapter 7: A Little Bird Told Me

Nikolai Rostov’s orderly, Lavrushka, is captured by the French and brought before Napoleon. The French historian Thiers gave an account of this conversation between a cossack and the emperor. Tolstoy revises it to switch the roles and make Lavrushka cunning and Napoleon a dupe. The emperor lets him go, and he returns to Rostov, thinking up new and better stories to tell.

How does this chapter challenge the role of historians in the ‘making’ of history?

Napoleon rode on, dreaming of the Moscow that so appealed to his imagination, and the bird restored to its native fields galloped to our outpost, inventing on the way all that had not taken place but that he meant to relate to his comrades.

A rather neat little chapter here, with Tolstoy reading (and writing) in between the lines of the history books. The historian Adolphe Thiers writes that Napoleon duped a Cossack with his plain appearance. Tolstoy says the Cossack was drunk and entertaining himself by outwitting the French emperor.

For both Lavrushka and Napoleon, their imagination and the stories they tell matter more than what actually happens. This creates a nice bit of symmetry with the previous chapter and the chatter in the salons, where everything is form with no substance, and lies abound.

Little birds

It is probably accidental, but I can’t help noticing the repetition of bird imagery from Chapter Four. There, artillery bombardment is described incongruously as ‘swooping downwards like a little bird.’ Shortly after, we hear the cook wailing: ‘Little birds, dear white little birds! Don’t let me die!’

Napoleon imagines the Cossack Lavrushka as a bird set free, but Lavrushka is perhaps a bird that can never be captured. I don’t know what to make of this little nest of avian images, but I like it nonetheless.

Chapter 8: Dearest

Andrei’s father and sister are not in Moscow. At Bald Hills, the old prince awoke as from a dream and vowed to defend his home to the death. Marya refused to leave him and he said much that could not be unsaid. Soon after, he had a stroke, and Marya took him to Bogucharovo. Three weeks pass. He asks to see Marya, telling her with great difficulty that he loves her and wants her to forgive him. He dies on a hot and sunny day, as Marya walks through the lime trees Andrei planted.

Marya • Mademoiselle Bourienne • Nikolushka • Nikolai Bolkonsky • Tikhon

In the end, did Marya hear what she needed from her father?

How do you expect his death will change Marya’s life?

Andrei’s oak and Marya’s lime trees

Princess Marya stayed on the veranda. The day had cleared, it was hot and sunny. She could understand nothing, think of nothing, and feel nothing, except passionate love for her father, love such as she thought she had never felt till that moment. She ran out sobbing into the garden and as far as the pond, along the avenues of young lime trees Prince Andrei had planted.

The lime or linden tree was sacred in ancient Slavic mythology. In Baltic mythology, the goddess of fate took the form of a cuckoo and lived in a linden tree. Ovid’s Metamorphoses tells the story of an old married couple called Baucis and Philemon. When they died, the woman became a linden, and the man was turned into an oak.

Andrei, of course, learned to live again through his proximity to a gnarly oak growing new shoots in Spring. Until then, he had been living only for himself and his family at Bogucharovo, improving his estate and – among other things – making a pond and planting lime trees.

These young virtuous trees now connect Marya to Andrei at the moment of their father’s death. Andrei planted them when he believed only in his family. She runs among them as her love for her father engulfs her. Both children have struggled to escape his orbit. Now, their dark star is gone, and now they must find new ways to navigate an uncertain fatherless future.

‘I wished for his death! Yes, I wanted it to end quicker … I wished to be at peace … And what will become of me? What use will peace be when he is no longer here?’

‘Dreadful mystery’

Tolstoy had a lifelong fascination with and curiosity about death. In other places, he imagines what it might feel like to die. Here, he shows us what it is like to lose someone we love. He shows the ‘torment of joy and terror’ in finite expressions that cannot be repeated. He explores the guilt of outliving someone else and wishing ‘it to end quicker’. And he presents Marya with the thing itself, the absence of a life:

All the force of the tenderness she had been feeling for him vanished instantly and was replaced by a feeling of horror at what lay there before her. ‘No, he is no more! He is not, but here, where he was, is something unfamiliar and hostile, some dreadful terrifying repellent mystery!’

This chapter rises far above our limited understanding of Nikolai Bolkonsky and his children. Like so much of War and Peace, it is a mirror to our own inner life, and it breaks our hearts not because of how we think about the Bolkonskys but because of how we feel about those we have lost, and those we stand to lose.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that I must be doing something right!

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

Reading your wonderful post, Simon, it’s hard to believe how much ground we’ve covered this week—and it feels like we’ve read a series of short stories, each one so powerful and complete in itself…

Hello. I've not posted for some time because I regret to inform you that I couldn't do the slow read of War and Peace.

I HAD to keep reading at breakneck speed and finished the book two months ago!

I'm posting now to let you know, if you don't know already, that there is a critically acclaimed film adaptation in Russian from the 1960s by Mosfilm.

In four episodes. Each episode is over two hours long.

Free to view on YouTube.

I've just started to watch it and so far so good. It is done on a grand scale and is very evocative of the period.