Mirror (Part 2/2) / Light

Wolf Crawl Week 52: Monday 23 December – Sunday 29 December

📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 52 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the second half of ‘Mirror, June–July 1540’ and ‘Light, 28 July 1540’. This runs from page 847 to 875 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “Edmund Walsingham, the Lieutenant of the Tower, comes next day.” It ends: “…tracking the light along the wall.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Next year, I will be revising these posts and turning them into a podcast, furnished with some original music and illustrations. In Wolf Crawl 2025, I am collaborating with two exceptionally talented people.

will bring weekly pieces from the archive to complement our reading, and is making a series of maps to help us navigate Cromwell’s world.Please recommend this read-along to anyone you think would enjoy it. And if you are in a position to do so, consider giving someone a gift subscription to Footnotes and Tangents, so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

He is moved to the Bell Tower, where Thomas More spent his last months. More had the liberty of the garden, but he will be under lock and key. When he enters the lower room, More gets up to leave. Martin tells him you can hear Bishop Fisher in the room above, whether you believe in ghosts or not.

Rafe reads his master’s letter twice to the king, who says, ‘I could free Cromwell, could I not?’ But Gardiner has told Henry that Cromwell will always be the cardinal’s man, and he will never ever forgive. Sadler cries and curses Seymour, Cranmer and Wyatt while he, Cromwell, imagines the king’s opportune death.

He teaches Christophe the three-card trick and picks up the images in his memory. Wolsey returns at last to talk, and he sees More at the table. He wonders how they will remember him, and how it is that men like Riche, Pole and Lord Lisle could better him in the end.

There are fresh allegations of corruption, and Norfolk boasting about his niece. He, Cromwell, warns Thomas Howard as Margaret Pole once warned him: ‘The ground beneath our feet is slippery.’ The cardinal comes in to complain about his burial, and he, Cromwell, remembers More at Lambeth Palace, giving Tom of Putney pennies to stay quiet. He never did.

Now Gregory must write a letter repudiating him. Richard must not wear black. On the afternoon of 27 July, he is told the hour and the manner of his death. Tomorrow, by the axe, at Tower Hill. 28 July 1540. The king will marry, and he will die.

‘Get me up, get me up –’ His father’s last words. The Cromwell household is dissolved, and Call-Me moves into Austin Friars with the leopard. On his last night, Cromwell prays, his inner self roaming back into the past and out towards an uncertain future. He sleeps.

He wakes. He eats, takes his coat and coin for the headsman. He pictures the world carrying on without him. Wyatt is at the foot of the scaffold, his last friend before he climbs. Up there, he listens to his heart. But here is our entirely beloved Christophe cursing the king, saying what you must not.

He pays the headsman, and he kneels. He looks for his master to follow, but his father is here. Walter Cromwell bellows, ‘So now get up. So now get up.’

But he cannot, for it is over.

‘This is what life does for you in the end; it arranges a fight you can’t win.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Christophe • Martin • Rafe Sadler • Stephen Gardiner • Norfolk • William Kingston • Thomas Wyatt

This week’s theme: And now no more for lack of time

'So now get up.' Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned towards the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

The opening lines of Wolf Hall placed us behind the eyes of a fifteen-year-old boy, beaten close to death by his father. Walter’s words were a sneer, directed at us; a presumption of failure. We weren’t expected to get up. The world did not want us to succeed. It is as though everything that has happened since has been our reply to Walter; which is why when Cromwell was made an earl, he wished to tell his father, ‘and see his face.’

Walter’s last words, ‘get me up, get me up –’ are a reversal of those he hurls at his son. Walter believed the Cromwells had been cheated and robbed by life, lords and lawyers. Full of grudge and grievance, he believed they owed him to get him up.

When Cromwell left home, he made money with the three-card trick. Your opponent must find the queen, but you make sure they don’t. Later, he would play the game for real: making Katherine and Anne disappear, then finding Anna and Jane. In 1532, he went to Calais. While looking for the memory machine, he found Christophe:

'You understand me, monsieur.' Christ, of course I do. You could be my son. Then he looks at him closely, to make sure that he isn't; that he isn't one of those brawling children the cardinal spoke of, whom he has left by the Thames, and not impossibly by other rivers, in other climes. But Christophe's eyes are a wide, untroubled blue.

Christophe is his only living companion the night before he dies. He teaches Christophe the three-card trick, ‘So if you are ever without money or food, the lady will provide.’

The lad was about fifteen when we first met him, the same age as Cromwell at the start of Wolf Hall. One of the few entirely fictional characters in the books, he is Cromwell’s shadow, a Calais version of himself. On his way to the scaffold, he orders Christophe not to interrupt his prayers. ‘No fighting.’

But Christophe has no guile. His role in the novels is often like a fool, to say what Cromwell cannot. Cromwell tells Wyatt that he forgives the king. For the sake of his family, he will die a penitent traitor. But here is Christophe, claiming Cromwell’s name and cursing Henry Tudor:

‘Henry King of England! I, Christophe Cremuel, curse you. The Holy Ghost curses you. Your own mother curses you. I hope a leper spits on you. I hope your whore has the pox. I hope you go to sea in a boat with a hole in it. I hope the waters of your heart rise up and spout down your nose. May you fall under a cart. May rot rise up from your heels to your head, going slowly, so you take seven years to die. May God squash you. May Hell gape.’

Christophe’s words echo Cromwell’s own thoughts about Thomas More: ‘When the Giant kills Jack, the Giant himself begins to fail. He is worn down and diminished with loneliness and regret. But it takes the Giant seven years to die.’

In a little under seven years, Christophe’s curse will get its man: Henry died on 28 January 1547. One imagines that Christophe Cremuel does not survive long after this speech, having so publically wished for the king’s death. In reading the trilogy we feel something of the suffocation and claustrophobia of the Tudor court. But thanks to Christophe, at the end, we can hear ourselves howl.

His surrogate son is hauled away. He doesn’t know whether his real son, Gregory, or Rafe or Richard, are in the crowd. He doesn’t look. ‘And now no more for lack of time.’ Instead, he looks to where he must follow. To the two fathers who began this story, Walter and Wolsey. Wolsey and Walter. As always, he wants to follow his master’s scarlet robe. But as always, it is Walter, not Wolsey, who stands above him now:

‘So now get up.’ He lies broken on the cobbles of the yard of the house where he was born. His whole body is shuddering. ‘So now get up. So now get up.’

Here is the song, ‘The Jolly Forester’ or ‘I Have Been a Foster’, which Cromwell hears as he walks to the Bell Tower:

‘So I won't see August, he thinks. The hares that flee the harvester, the cold morning dews after St Bartholomew's Day. Or the leaf fall, the dark blue nights.’

Footnotes

1. Martin

'Martin, is it you? You look well. How's my god-daughter?'

We first met Martin at the end of Wolf Hall, when his ward was Thomas More, and Cromwell was the one asking all the questions. Martin’s daughter is named Grace, after Cromwell’s own daughter, and the gaoler is a good Gospeller – although perhaps not good enough to teach Grace how to read. He has seen More and Fisher, George Boleyn, Harry Norris, Thomas Wyatt, Tom Truth and Geoffrey Pole all pass through his cells. He once said, ‘I trust it shall be many days before I see you here.’

'Why not trust it will be never?' Avery says.

Ah, yes, Thomas Avery. A fellow Putney lad. Cromwell decides he does not need to send a message to his accountant on his way to the scaffold. ‘Avery doesn’t need telling twice.’ He is charged with securing Cromwell’s offshore trust fund for his children.

2. The Pillar Perished

‘Wyatt will write a verse about me,’ Cromwell tells a tearful Rafe. Sources suggest Wyatt did attend Cromwell’s execution, but like his other friends and allies, he would have been careful not to defend Cromwell publicly. And this was Wyatt. As the king told Cromwell, ‘What he says he does not mean, and what he means he does not say.’ But shortly after Cromwell’s execution, he adapted verse by Petrarch into one the earliest examples of the English sonnet. It may well be a verse about Thomas Cromwell:

The pillar perish’d is whereto I leant;

The strongest stay of mine unquiet mind:

The like of it, no man again can find,

From east to west still seeking though he went.

To mine unhap; for hap away hath rent

Of all my join the very bark and rind;

And I, alas! by chance am thus assign’d

Dearly to mourn, till death do it relent.

But since that thus it is by destiny,

What can I more but have a woeful heart;

My pen in plaint, my voice in woeful cry,

My mind in woe, my body full of smart,

And I myself, myself always to hate

Till dreadful death do ease my doleful state.

3. Cromwell imagines the king’s death

The thought has entered his mind before now: what if a fever rises this very night, what if he coughs and strains to breathe, what if his lungs fill with water again and the poison from his leg kills him?

Many times during these books, our characters have come up against the tripwire of treason: imagining the king’s death; picturing a world without Henry. Here, Cromwell cannot help but hope that his life would be spared if the king choked on his own venom tonight.

The dramatic irony is that Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, will be saved from execution by the timely death of Henry in 1547. Uncle Norfolk was attainted for treason on 27 January and was due to die the next day. His king died in the early morning of 28 January, and Edward VI’s councillors chose not to begin the new reign with bloodshed.

4. The cardinal complains of his burial

‘Why do I not have the right tomb?’ he says, ‘when I paid so much to that Italian of yours?’

Readers with long memories will remember that Cromwell was in charge of Wolsey’s legacy project: his colleges at Oxford and Ipswich, and his grandiose sarcophagus that Henry pinched, but ultimately will contain Lord Horatio Nelson. It was carved by Italian craftsmen, and the cosmopolitan Cromwell was Wolsey’s ‘Italian’ fixer.

In Wolf Hall, Cromwell and Cranmer were summoned in the early hours to the king’s bed-chamber, where Henry was troubled by dreams of his brother Arthur. ‘The dead do not complain of their burial,’ Cranmer reassured his king. Well, here’s Tom Wolsey, to prove otherwise.

Or is he? Cranmer argued that Henry had not seen his brother’s ghost. Cromwell cynically convinced the king that his brother wanted him to fulfil his Arthurian destiny. On other occasions, Cromwell clearly states that he does not believe the dead speak. The gaoler Martin tells him he has heard Bishop Fisher at night.

'You shouldn't believe in ghosts,' he says uncertainly. 'I don't,' Martin says. 'But who are they to care, if I believe in them or not?'

This is a key idea that holds the trilogy together: Cromwell is the rational-minded moderniser who wants to sweep away all superstition. But the past holds fast, and even if we don’t believe in them, the ghosts believe in us. They are memories, shared and individual, folded into places and objects, sounds and smells.

So Cromwell’s Wolsey is a piece of him. Like Thomas More, or the eel boy, ‘looking at him from the corner of the room.’ Why has Wolsey returned at this late hour? I think it is because the charge of treason has levelled them. When he was magnificent, Cromwell feared he had become great by clambering over the cardinal’s corpse. Dorothea said as much. Now they are both dead; and he can talk to Wolsey once more, as equals; ghost to ghost.

5. The Quaresima Torture Protocol

No rain falls. The heat does not falter. It seems Henry means to kill his slave through sheer disuse.

While Cromwell is waiting to learn whether he will be beheaded, burned, or disembowelled, his mind wanders back to Italy. There was indeed a ruler of Milan called Galeazzo II Visconti, who devised with his brother ‘a torture regime that lasted for forty days.’ Hilary Mantel likely read of this in Barbara W. Tuchman’s brilliant history of the 14th Century, A Distant Mirror.

The Visconti perhaps used their Quaresima as a threat to frighten people. They were masters of the horror genre, like Thomas Cromwell and Hilary Mantel herself. There is very little actual blood and gore in the Cromwell trilogy. The worst scenes are the public burnings of Joan Boughton and John Lambert. As Cromwell tells Wriothesley in Bring Up the Bodies, ‘the mind is its own best torturer.’ These books haunt us by setting our imagination to work and by putting us in the chair.

6. The first flight of Daedalus

He sees Icarus, his wings melting, plummeting into the waves. It was Daedalus who invented the wings and made the first flight, he more circumspect than his son: scraping above the labyrinth, bobbing over the walls, skimming the oceans so low his feet were wet. But then as he rose on the breeze, peasants gaped upwards, supposing they were seeing gods or giant moths; and as he gained height there must have been an instant when the artificer knew, in his pulse and his bones, This is going to work. And that instant was worth the rest of his life.

Back in Week 33, I shared this painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, and the poem it inspired by W. H. Auden. Our instinct is to compare Cromwell to Icarus, the boy who flew too close to the sun. He told Francis Bryan that he had wings, and the Vicar of Hell told him to ‘flit into the dusk … before they melt.’

But Cromwell identifies with Icaraus’ father. He wondered, ‘Why do we blame Daedalus for the fall, and only remember his failures?’ Daedalus is the inventor, the master craftsman who outwitted King Minos by escaping the labyrinth on wings made from feathers, thread and beeswax. Daedalus designed the labyrinth that became his prison. Cromwell perfected the machinery of justice that will kill him.

This quotation is one of my favourite passages from the entire trilogy. Cromwell asks us to forget for a brief moment the death of Icarus and the failure of the fall. It is what Mantel has been doing throughout the books: letting us feel the full ecstasy of the fleeting moment while simultaneously seeing the shadows on the future. How do we capture the vitality of that instant, while knowing its sad conclusion? That has been Mantel’s task, and her accomplishment.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder captures another moment. Icarus has fallen and drowns in the bottom right corner of the painting. His picture shows the world untroubled and unconcerned by this tragic end. In his mind’s eye, Cromwell paints his own world without him:

It occurs to him that when he is dead, other people will be getting on with their day; it will be dinner time or nearly, there will be a bubbling of pottages, the clatter of ladles, the swift scoop of meats from spit to platter; a thousand dogs will stir from sleep and wag their tails; napkins will be unfurled and twitched over the shoulder, fingers dipped in rosewater, bread broken.

7. Afterlives

Walsingham says, 'The Duke of Norfolk has asked that your lordship be informed – the king marries Katherine Howard tomorrow.'

Oh, how Uncle Norfolk must have loved that! In case you missed it, there is an Author’s Note at the end of The Mirror and the Light, where Hilary Mantel tells us what happened to our characters after Cromwell left the stage.

Henry’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, will go to the block on a charge of adultery with Thomas Culpepper. Jane Rochford will be beheaded for her role in the affair.

As mentioned above, Norfolk narrowly avoided his execution on the eve of Henry’s death. His son, the spidery Earl of Surrey, was beheaded the week before. Thomas Wriothesley and Richard Riche both served as Lord Chancellor, and under Mary I, Stephen Gardiner and Reginald Pole persecuted their religious opponents: burning both Cranmer and Latimer at the stake.

Gregory Cromwell died young. Richard gave Cromwell’s name to his descendant, Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of what Mantel describes devilishly as ‘the first English republic.’ Rafe Sadler survived and thrived in royal service, dying in 1587, ‘the richest commoner in England.’ Not bad for a half-drowned hedgehog.

8. Brave New World

He says to the sheriffs, 'There is a Plymouth man, William Hawkins, has fitted a ship for Brazil. He is taking lead and copper, woollen cloth, combs and knives and nineteen dozen nightcaps. I would have liked to know how that works out.'

The attention to detail here makes me think Mantel saw a document that passed over Cromwell’s desk in 1540, concerning William Hawkins’ voyage to Brazil. If so, it wasn’t his first. In around 1528, he became the first Englishman to sail to the South American mainland. His son, John Hawkins, played a prominent role in establishing the Atlantic slave trade. John’s cousin was Francis Drake, another slaver, and the captain of the second circumnavigation of the globe.

When the cardinal died, Cromwell thought: ‘What was England before Wolsey? A little offshore island, poor and cold.’ In the 1530s, Cromwell had built a dubious case for calling England an empire, and Henry its emperor. In asking about Hawkins’ ship, Cromwell nods to England’s dark future as a global superpower built on naval dominance and a trade in human lives.

9. I am as I am

At the foot of the scaffold, Cromwell sees Wyatt. ‘Between his prayers,’ he hears Wyatt’s poem, ‘I am as I am’. One verse reads:

Yet some that be that take delight

To judge folks thought for envy and spite,

But whether they judge me wrong or right,

I am as I am and so do I write.

Mantel’s Cromwell believed Henry would lament killing him. And true enough, in winter 1541, the king attacked his council for making him ‘put to death the most faithful servant he ever had.’ The ever resourceful Bess Seymour took advantage of the king’s contrition to get her husband’s land and titles restored, and Gregory elevated to the peerage as Baron Cromwell.

Diarmaid MacCulloch’s biography makes the compelling argument that Cromwell was a masterful statesman with a fascinating life story. But I don’t think Hilary Mantel’s trilogy is about rehabilitating his reputation or lionising Master Secretary. It is not about judging him ‘wrong or right’, as Wyatt says. It is about seeing Cromwell as a man who was alive. Mantel said, ‘History is not the past – it is the method we have evolved of organising our ignorance of the past.’ Historial fiction is not the past either, but it is the imaginative work that must be done so that we can meet the dead as we do the living: listening with our full selves.

Brother men, you who live after us,

Do not harden your hearts against us.

François Villon, opening epigraph to The Mirror and the Light.

For you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. When the darkness is dispelled, our descendants will be able to walk back, into the pure radiance of the past.

Petrarch, closing epigraph to The Mirror and the Light.

Quote of the Week: Winter is here

The last paragraph is the last pulse-beat of Thomas Cromwell. As the old wives predicted, this summer, we have it hot. Like a good Englishman, he complains of the weather: ‘An Englishman dies drenched, in the rain that has enwrapped him all his life.’

But death is cold: it takes him to Launde in the snow. He pictures the former abbey where he hoped to retire. Earlier in the novel, he described Launde as standing ‘in the heart of England, far from the dangers of salt water.’ Now, death takes him from Launde, from England, ‘from the waters salt and fresh.’

Death comes like the Thames – the tug of the tidal river has flowed through these books as it bisected Cromwell’s life: born in Putney on the south bank and dead at Tower Hill, downstream on the north shore.

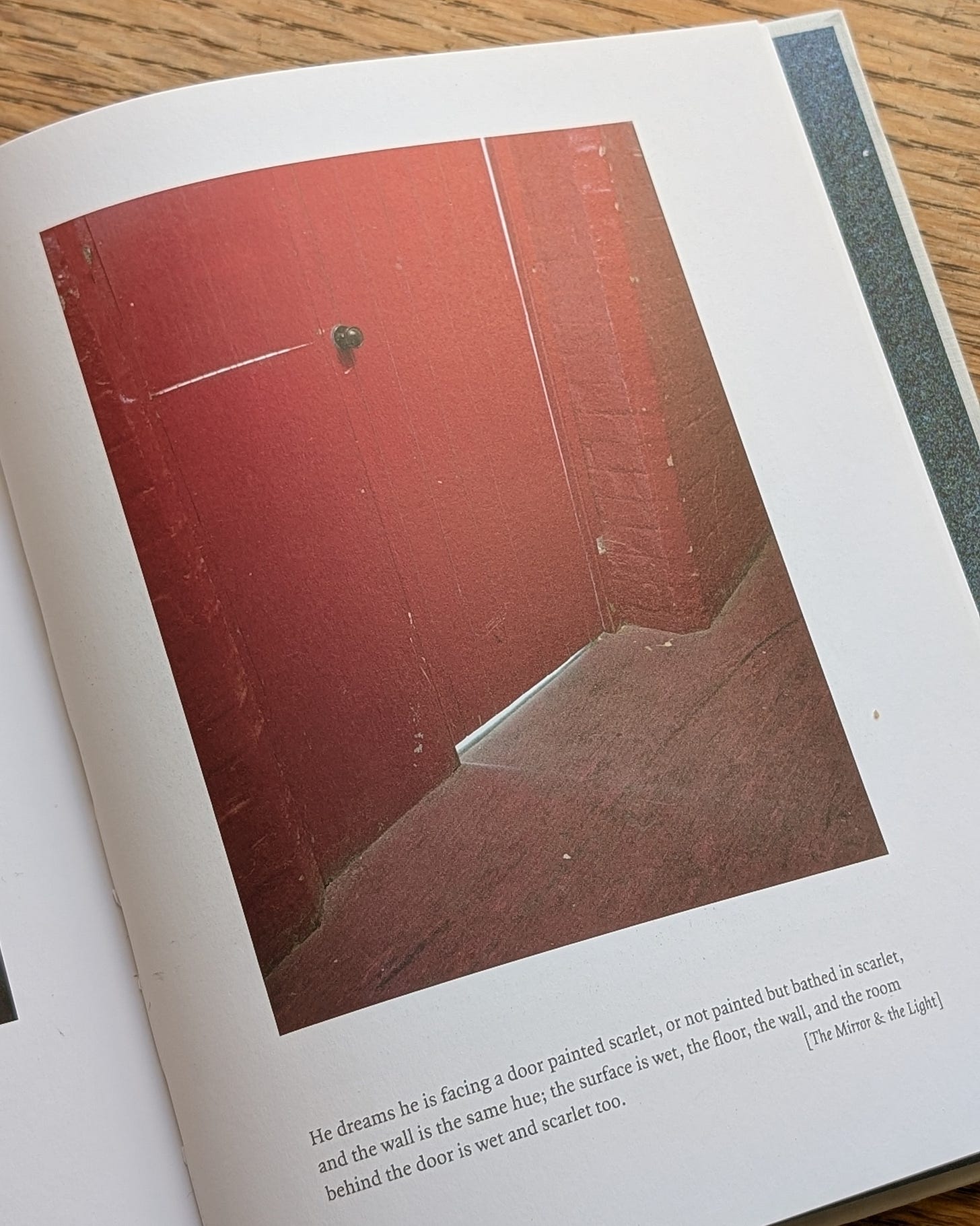

In the Tower, he dreamed of a door ‘bathed in scarlet’. He can tell his story in doors, in chairs and stools, steps and ladders. In mirrors and light. His last ripple of conscious self feels for that door, and tracks his last light along the wall.

He is very cold. People imagine the cold comes after but it is now. He thinks, winter is here. I am at Launde. I have stumbled deep into the crisp white snow. I flail my arms in angel shape, but now I am crystal, I am ice and sinking deep: now I am water. Beneath him the ground upheaves. The river tugs him; he looks for the quick-moving pattern, for the flitting, liquid scarlet. Between a pulse-beat and the next he shifts, going out on crimson with the tide of his inner sea. He is far from England now, far from these islands, from the waters salt and fresh. He has vanished; he is the slippery stones underfoot, he is the last faint ripple in the wake of himself. He feels for an opening, blinded, looking for a door: tracking the light along the wall.

Thank you

We have come to the end of our slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. Thank you so much for joining me on what has been a labour of love and a tribute to Mantel’s magnificent creation. If you have found this journey rewarding and would like to show your appreciation, I’ll rattle my tip jar one last time:

Next year, I will be revising these posts and turning them into a podcast, furnished with some original music and illustrations. In Wolf Crawl 2025, I am collaborating with two exceptionally talented people.

will bring weekly pieces from the archive to complement our reading, and is making a series of maps to help us navigate Cromwell’s world.Please recommend this read-along to anyone you think would enjoy it. And if you are in a position to do so, consider giving someone a gift subscription to Footnotes and Tangents, so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025.

I have been your guide, Simon Haisell, and this has been Wolf Crawl.

Thank you for reading and happy new year!

Yesterday, December 23, while my family was out doing holiday tasks, I finished baking Christmas cookies. As I worked, I listened to the last few chapters of Mirror and the Light. (A slightly odd juxtaposition of task and mood, I grant you. But, like Cromwell, I was running out of time.) I had actually been delaying reading them because I didn’t want it to be over. Even though we know the end when we begin! Thank you so much, Simon, for all your efforts; a true highlight of 2024!

I cried through the final pages — I am stunned again and again at Hilary Mantel’s wizardry of writing — and then had to answer the door when a neighbor dropped off a quick bread Christmas gift. I decided there was no way I could explain my red eyes and had to let her think whatever she might. How could I explain how much Cromwell had gotten into my head this entire year? How sad I was to be saying goodbye to him at the scaffold? How deeply pleased I was by the decision to join Simon and everyone else for this 2024 reading adventure? This has been one of the enduring sparks of joy in this disturbing year. My hat is off to you, Simon, for a beautiful job well done!