Welcome to week 19 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 2, Part 3, Chapter 24 – Part 4, Chapter 4.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s theme: Never Never Land

Welcome to Never Never Land, where we wait for life to begin again.

At the start of Part Four, Tolstoy tells us that humanity lost its ability to enjoy pure idleness when it was banished from the Garden of Eden:

If man could find a state in which he felt that though idle he was fulfilling his duty, he would have found one of the conditions of man's primitive blessedness.

When Nikolai Rostov doesn't think too hard about it, military life offers him these blessed conditions. That is, if you forget the trauma of war, the hollow hunger, the nightmare of the hospital, and the nagging feeling you are wanted at home.

‘For God's sake, I implore you, come at once, if you do not wish to make me and the whole family wretched.’

It is worth remembering, then, that Nikolai's ineffective shrubbery-based rage and bloodlust on the hunt are ripples on the water caused by stones thrown at Schöngrabern, Austerlitz and Tilsit. He is hunted by the shadows behind him.

This week, four young people are waiting for their lives to move forward.

Andrei takes the water cure in exile, waiting for a year to pass in Switzerland. His father set the test, and he accepted it. But alone on his magic mountain, he has too little to do and too much time to think. He begs the future to come take him.

Marya sees little light at the end of the tunnel. Her only solace is a pilgrim fantasy of ‘hempen rags’ and ‘an assumed name’, a dusty road that may lead to a ‘place where there is no sorrow or sighing, but eternal joy and bliss.’

Natasha waits for her betrothed to return. She is ‘even-tempered and calm, and quite as cheerful as of old.’ This blessed idleness strikes her family as unnatural. It makes them doubt the seriousness of her feelings. But remember Eden.

Nikolai engages in a different kind of idleness: the fantasy of the hunt, play-acting at war and at life. He has been promoted by his superiors and is loved by his family, but memories of Austerlitz and of Dolokhov rise in his mind to remind him of his unlucky star.

The wolf hunt leads us away from soirées and ballrooms to the edge of the world. Here, the normal rules do not apply. A young woman defies her menfolk to join the chase. A serf castigates his master. An elderly man takes a woman's name.

This is carnival time. The world outside the world, before life and death return to bite.

Chapter 24: Hearts of gold

Andrei visits the Rostovs regularly, but the betrothal is kept secret. The betrothed couple gets to know one another and finds common ground. Andrei tells Natasha to confide in Pierre, who "is a most absent-minded and absurd fellow" but with a "heart of gold." Andrei remembers his parting with Natasha for a long time afterwards. For the next two weeks, Natasha becomes quiet and withdrawn. When she returns to normal, something subtly changes in her character.

Andrei • Natasha • Sonya • Pierre • Countess Rostova • Count Rostov

Is Andrei right to tell Natasha to trust Pierre’s advice and guidance?

How do you interpret Natasha’s sudden changes in mood?

Chapter 25: Dear Julie

At Bald Hills, the old prince's health and temper are getting worse. He takes it all out on Marya, attacking her religion and the way she cares for Andrei's son. Andrei visits and Marya notices he is more gentle and happy than he has been for a long time. She writes to Julie, who has just lost her brother in the war. She does not believe the rumours about her brother and Natasha.

Nikolai Bolkonsky • Marya • Mademoiselle Bourienne • Julie • Andrei

What do you think about Marya’s opinion of Natasha? Do you think she is right?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of Marya’s religious convictions?

Chapter 26: The Secret Pilgrim

Six months pass. Andrei writes to Marya from Switzerland, informing her of the betrothal. He asks her to give the letter to their father and get his agreement to shorten his exile. The letter angers the old prince, who threatens to marry Bourienne. "Wait until I am dead," he says. Marya thinks about her private dream to become a pilgrim, running away to a place without "sorrow or sighing".

Andrei • Marya • Nikolai Bolkonsky • Mademoiselle Bourienne

Marya’s situation has no easy solution. What advice would you give her at this point in the story?

Andrei taking the waters

Andrei writes to Marya:

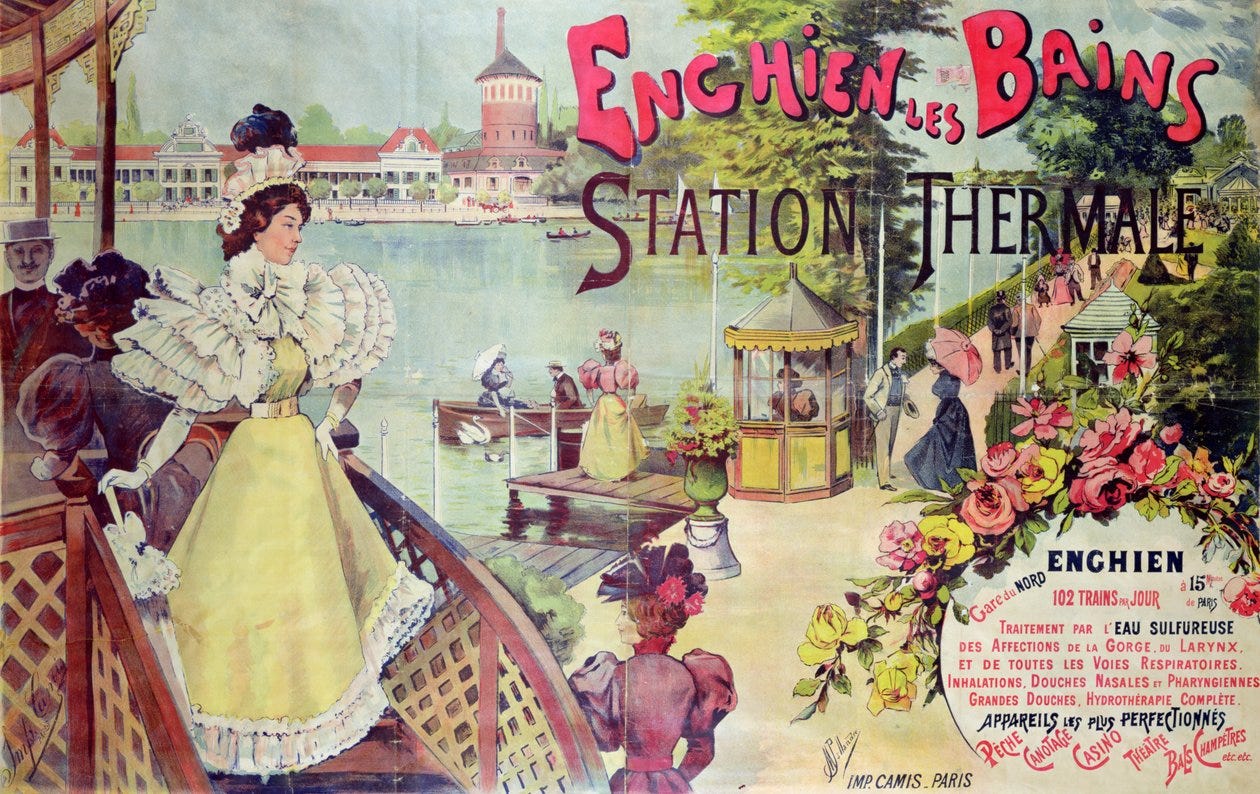

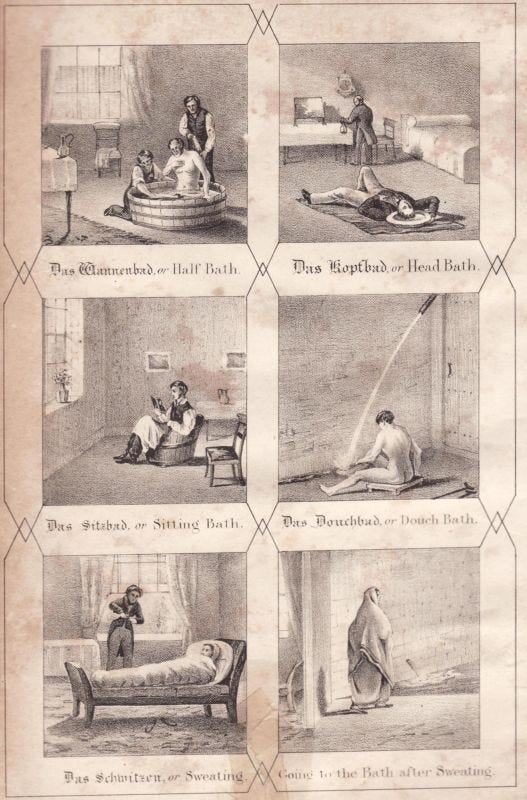

If the doctors did not keep me here at the spas I should be back in Russia, but as it is I have to postpone my return for three months.

This section of the book closes with a worrying note from Andrei, impatient to return home but detained by his doctors at a Swiss spa resort. We know that he sustained an almost fatal wound at the Battle of Austerlitz, which took many months to heal. Marya tells Julie that he “has grown physically much weaker. He has become thinner and more nervous.”

Andrei is caught up in the modern revival of hydrotherapy, or the water cure, the belief in the medical benefits of drinking and bathing in pure water from natural springs. Later in the century, spa resorts became more established across Europe, and famous water cure patients included Charles Dickens, Florence Nightingale and Charles Darwin.

Alongside hydrotherapy, the nineteenth century saw the spread of sanatoriums in alpine and countryside retreats for convalescent patients. These were especially associated with the treatment of tuberculosis, known then as consumption, and first identified as a single disease in the 1820s.

Alpine sanatoriums provide much inspiration for literature. In our discussion, readers mentioned the most famous example: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, as well as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night, and Hernan Diaz’s Trust. Let us know of other examples in the comments.

Congratulations on completing Book 2, Part 3 of War and Peace. Have a badge!

BOOK 2 PART 4

Chapter 1: The matter-of-fact man

Nikolai has taken over Denisov’s squadron and lives a blessed life of idleness in the army. His mother’s ominous letter recalls him home. At Otradnoe, life goes on as before, but with an uneasiness caused by the bad state of their affairs. Nikolai thinks Natasha does not seem like a girl in love, and their mother also has doubts about the marriage.

Nikolai • Natasha • Count Rostov • Countess Rostova • Sonya • Petya

Do you agree with Tolstoy’s thoughts on idleness? Can we be truly happy doing nothing?

How has Nikolai changed since the start of the novel?

Dancing the Trepak

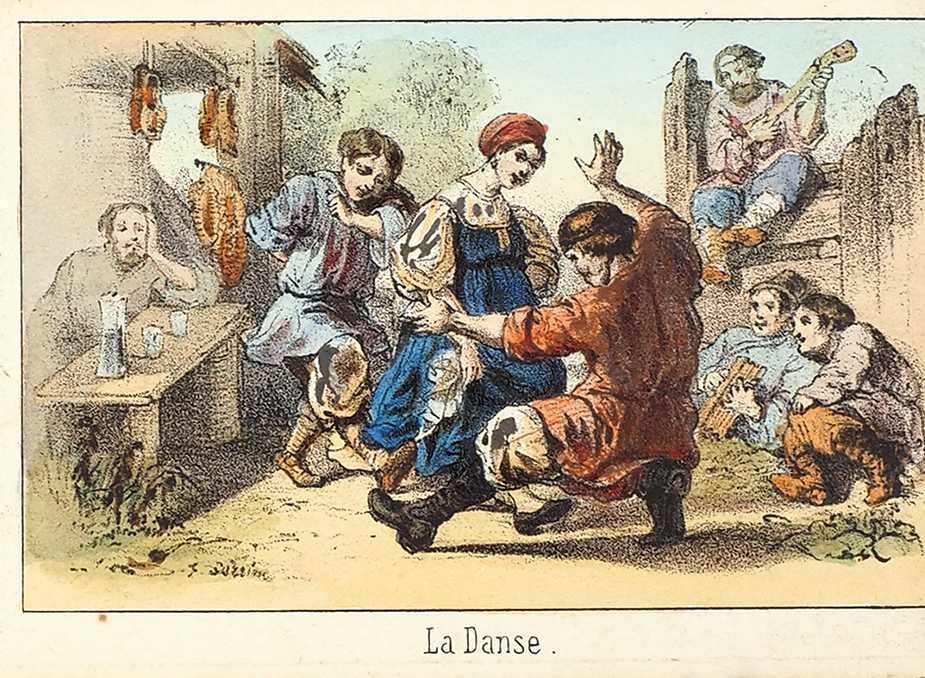

Nikolai is given a fabulous send-off before returning home:

His hussar comrades—not only those of his own regiment, but the whole brigade—gave Rostov a dinner to which the subscription was fifteen rubles a head, and at which there were two bands and two choirs of singers. Rostov danced the Trepak with major Basov; the tipsy officers tossed, embraced, and dropped Rostov; the soldiers of the third squadron tossed him too, and shouted ‘hurrah!’, and then they put him in his sledge and escorted him as far as the first post-station.

This is reminiscent of Denisov’s glorious farewell booze-up on leaving Moscow. Speaking of which, the lisping dandy is mentioned three times in this chapter, but there are no further details about his whereabouts.

The trepak or tropak is a traditional Cossack dance from Russia and Ukraine. It is an especially energetic dance and was famously adapted for ballet as the “Russian Dance” in Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker:

Chapter 2: An account of everything

Nikolai decides to get business matters out of the way first and demands an account of everything from a frightened Mitenka. Nikolai loses his temper, and Mitenka ends up in a shrubbery. He calls the steward a thief, and his father is embarrassed by the whole situation. Nikolai tears up a debt owed by Anna Mikhailovna, abandons business affairs and devotes himself instead to hunting.

Nikolai • Mitenka • Count Rostov • Countess Rostova

Would you agree that Nikolai does everything wrong in this chapter? What would you have done differently?

Chapter 3: Hunting season

It is mid-September, and the weather is perfect for hunting. Nikolai consults with the head huntsman, Danilo, a man disdainful of everyone. Just before they set off, Natasha and Petya arrive and demand to come too. “It is my greatest pleasure,” says Natasha Rostova.

Nikolai • Danilo • Natasha • Petya

What do you think attracts Nikolai to the hunt?

Are you surprised that Natasha wants to join the chase?

The weather was already growing wintry, and morning frosts congealed an earth saturated by autumn rains. The verdure had thickened, and its bright green stood out sharply against the brownish strips of winter rye trodden down by the cattle, and against the pale yellow stubble of the spring sowing and the reddish strips of buckwheat. The wooded ravines and the copses, which at the end of August had still been green islands amid black fields and stubble, had become golden and bright-red amid the green winter rye. The hares had already half changed their summer coats, the fox-cubs were beginning to scatter, and the young wolves were bigger than dogs. It was the best time of year for the chase.

Tolstoy and hunting

The next four chapters concern the Rostov hunt on their Otradnoe estate. For some, these are a few of the best chapters in War and Peace – with their contrasting images of gore and beauty, wildness and civilisation, life and death, joy and fear; it condenses the essence of the book down into one vivid extended scene. For others, it is the worst part of War and Peace, with its casual depiction of animal cruelty. I know some readers just choose to skip these four chapters entirely.

The young Tolstoy had a passion for hunting. In the winter of 1858, he and his brother went bear hunting. Tolstoy killed the first bear but a second one almost killed him, leaving him with a permanent scar on his forehead. A few weeks later, he caught up with the bear, and its skin became a rug at his home at Yasnaya Polyana. Many years later, he wrote it up as a story for children.

In the 1880s, his views on hunting radically changed. When he went out with his dogs he hoped his quarry would escape. In 1884, he abandoned hunting altogether and became a vegetarian.

Chapter 4: The hunt

The count joins the hunt, and they run into Uncle, a distant relative and neighbour of the Rostovs. Like Nikolai, Uncle clearly disapproves of the presence of Natasha and Petya. The count holds back with his old attendant, Semyon, as the hunt goes on ahead. They are joined by Natasha Ivanovna, the buffoon. Suddenly, the hunt turns towards them, and a wolf appears and escapes. Danilo curses and raises his whip to the shamefaced count.

Nikolai • Count Rostov • Natasha • Petya • Uncle • Danilo • Semyon • Natasha Ivanovna

Why do you think we start the hunt from the count’s perspective?

What do we learn about him from how he interacts with his serfs?

The Buffoon

We are familiar with court jesters and fools over in our slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy. By the nineteenth century, the tradition of household jesters declined in Western Europe but continued to flourish in Russia.

Natasha Ivanovna contrasts with the other cross-dressing character we met at Bald Hills: Ivanushka, one of Marya’s God’s folk, a woman dressed as a male pilgrim. Ivanushka is based on Marya Gerasimovna, a holy fool who visited Tolstoy’s mother at Yasnaya Polyana. She wandered Russia in men’s clothes and called herself ‘Ivan the Fool’, and became godmother to Tolstoy’s sister, Masha.

These are two different cultural traditions of foolishness. Ivanushka and Ivan the Fool belong to a tradition of ‘holy fools’ where their unconventional behaviour is associated with their religious devotion. In contrast, Natasha Ivanovna is a secular fool kept in the household for entertainment.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

I love the weekly audio. A great summary as always and very educational. Thank you Simon. Enjoy the rest of your weekend. Back tomorrow👍

Thank you for the systematization and questions, Simon. It immerses you very much in reading 📖

This story about “Ivan the Fool” is so tragic. It seems that the woman was not dressing up for fun at all, but for protection. Women in the early 19th century were generally not allowed to wander alone, at least everyone would have had a question. I wonder if Maria Bolkonskaya (pilgrim version) would end up dressing up as a man. or she would have to find a male companion.