📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 43 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading ‘Nonsuch, Winter 1537–Spring 1538’. This runs from page 523 to 562 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “‘My lord?’ a boy says. ‘A gravedigger is here.” It ends: “… and the name of the palace is Nonsuch.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

Winter, 1537. A gravedigger brings Cromwell a wax doll dug up from the frozen soil: the image of the baby prince, Edward, impaled with nails of iron.

The court is in mourning for our sweet mistress Jane, but the king’s council are restless. It is Cromwell’s job to deliver the message to Henry: England wants him to remarry. Norfolk favours a French princess; Cromwell considers Anna of Cleves and a Protestant alliance.

There is an Imperial proposal: Chistina, Duchess of Milan, the exiled queen of Denmark. But Henry is thinking of fellow red-haired Mary of Guise, nevermind that she is already betrothed to Scotland.

Meanwhile, the new French ambassador, Castillon, does not ingratiate himself with the king or his minister. Lewes Priory is to be blown up. And he, Cromwell, is a grandfather, with a little Henry to one day be councillor and friend to his first cousin, Edward Tudor.

Spring comes in: the hunting season; the doctors counsel the king against too many days in the saddle. Two men must be burned: a wooden saint from Wales and an unrepentant monk called Forrest. Oh, and Stephen Gardiner is coming home. But first:-

The king has taken a tumble. He lives, but once again Cromwell sees his future flicker before him. Henry must make him, Lord Cromwell, regent. ‘Set it down and seal it: multiple copies.’ But the king is talking to Norfolk and dreaming of a dynasty with Madame de Longueville. He, Cromwell, thinks: ‘What’s Henry up to?’

The Welsh idol Derfel is reduced to firewood to burn Father Forrest at Smithfield. He, Lord Privy Seal, watches dry-eyed and remembers his first burning, the Lollards and the dogs. He was never the same again.

Summer approaches. Henry’s future wives fade from view: Madame de Longueville arrives in Scotland and the Emperor loses interest in an alliance with the apostate English king. Instead, Henry turns his mind to a fairytale palace near Hampton Court. It will have no equal in Christendom. ‘And the name of the palace is Nonsuch.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Henry VIII • Christophe • Tom Truth • Meg Douglas • Lady Mary • Edward Seymour • Norfolk • Surrey • Thomas Wriothesley • Lady Rochford • Humphrey Monmouth • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Audley • Chapuys • William Fitzwilliam • Suffolk • Thomas Boleyn • Castillon • Gregory • Richard Cromwell • Eliza Tudor • Hugh Latimer • Doctor Butts • Doctor Cromer • Thomas Cranmer • Culpepper • Thurston

This week’s theme: Premonitions

‘My lord?’ a boy says. ‘A gravedigger is here.’ He looks up from his papers. 'Tell him to come back for me in ten years.'

Mantel is the master of mood, foreboding and dread. As the year turns, we must begin to think again: Who will the king marry and what will England look like after he is gone? A dangerous game of chess is underway. ‘He, the minister, must move on all fronts: bustle from board to board, pushing six queens at once.’

No one wants an early knock from a gravedigger. He may remind us of those jesting diggers in Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

‘What is he that builds stronger than either the mason, the shipwright, or the carpenter?’ ‘The gallows-maker, for that frame outlives a thousand tenants.’

And it is true: ‘Today’s will be a problem of bodies stacking up, the ground too hard to dig.’ Everywhere Cromwell looks, he sees the dead and dying. Truth dies in the Tower, the king slips from his horse, and a saint is burned at Smithfield to execute a monk, and exorcise the ghost of Joan Boughton.

Lately he has been tormenting Thurston with a design for a spit driven by a system of gears and pulleys, which uses the fire's draught to turn the meat at a steady speed. 'Voilà,' he says. Impaling a chicken.

‘The machinery is so much bigger than yon pitiful pullet,’ he tells Thurston. In our mind’s eye, we see a monstrous Tudor mechanism of turning wheels, dismembering ministers and wives in one smooth ‘regulated action.’

‘You kill your wives,’ the French ambassador tells Henry. From across the Narrow Sea, the King of England looks like a wild man from the woods. He marries only for love and then picks your bones clean later. His passion burns and leaves behind only charred remains. He is the same with his ministers. His Wolseys and Cromwells:

He says, ‘You know, Crumb, I may from time to time reprove you, I may belittle you. I may even speak roughly.’ He bows. 'It is for show,' Henry says. 'So they think we are divided. But take it in good part.'

This should reassure us when the king is dining with the Howards and the French ambassadors; when he is up-country with ‘the silken lout Culpepper’, far from Cromwell; when he is falling from his horse. But it does not reassure us.

I still have no plan, I have no route out, I have no affinity, I have no backers, I have no troops, no right, no claim.

The king admires his portrait and begins work on a palace. Neither portrait nor palace have survived. Fire took the painting. The Palace Nonsuch lacked an adequate water supply, and was dismantled by Charles II’s mistress to pay her gambling debts. If Henry is ‘the mirror and the light’, he will not shine forever. ‘He thinks, I must be ready for Henry’s death. But how shall I be ready? I cannot imagine.’

Meanwhile, the killing continues. ‘Beg pardon of your king!’ he tells John Forest, chained above a burning saint at Smithfield. He believes a man must bargain for his life. ‘Everybody wants something, if only for the pain to stop.’

He believes a man in Padua found the recipe for a long life: ‘One must eat the meat of the viper.’ And drink human blood. He watches Forrest burn and he does not cry.

So different from that child ‘at the wrong end of time’, heaving soundless sobs beneath a stand like the one where he now sits. The image of a burning woman, scarred on his mind’s eye. The dogs of London, hungry for Putney flesh. Closing in.

Oh, and Stephen Gardiner is coming home.

Footnotes

1. When life gives you oranges

Hilary Mantel opens this chapter with a beautiful sombre image of a wintry Thomas Cromwell:

The visitor pulls off his cap. He stares around; he sees a low-lit expanse, with nothing in it but Lord Cromwell before the barber gets to him, the Queen of Sheba hanging on the wall behind. Painted on the ceiling, the stars in their courses; on his desk, like a low winter sun, a dried orange.

Fresh oranges were a rare delicacy in Tudor England. Bitter ‘Seville’ oranges were imported from Spain: William Shakespeare makes a pun on their origin in the play “In Much Ado About Nothing” when a character is described as ‘civil as an orange.’

We can imagine Cromwell hankering after Meditteranean fruit from behind his desk in the cold dark winter of 1537. In 1562, Cromwell’s successor William Cecil, owned a solitary orange tree. But in the reign of Henry VIII, they were an expensive import and a luxury gift. Back in 1520, Henry Courtenay made the king a New Year’s gift of oranges; the Marquis of Exeter is currently enjoying his final winter on this good earth.

Cromwell meanwhile, has a little longer left.

Chapuys sends him a present of two hundred sweet oranges. He ships half down to Sussex for his son and grandson, and walks round Whitehall giving the rest out. The Bishop of Tarbes, newly arrived to join the French embassy, encounters him in air made lively by their zest.

When life gives you oranges, live like a lord.

Further reading:

2. Anna of Cleves

Norfolk asks Cromwell whether he has a list of prospective brides for Henry. Thomas Wriothesley says, ‘Of course he has a list … But he has more reverence than to produce it.’ However, it appears Call-Me knows at least one name on that list:

‘What do you hear from Cleves?’ 'No great praise, neither of the lady's face nor person.'

This is our first introduction to Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. Her appearance (in more ways than one) will be pivotal to the plot and the remaining months of Cromwell’s life. Hans Holbein will be sent out to paint her, but for now, we will make do with a lesser-known portrait of Anna, fortuitously featuring an orange.

Anna’s father John presided over a serious-minded court influenced by Thomas More’s old friend Erasmus and the ideas of the German Reformation. He married his eldest daughter Sybille to John Frederick of Saxony, the head of the Schmalkaldic League of Lutheran princes within the Catholic Holy Roman Empire.

So Anna is the ‘gospeller’s daughter’ that Uncle Norfolk thinks Cromwell prefers. In contrast, the arch-snob Thomas Howard believes Henry must marry a princess of royal blood.

3. Robin Hood

Robin Hood sings ballads about his deeds while he is doing them. A hundred times he escapes the noose and the sword. In the end he is betrayed and bled to death by a false prioress. His blood runs into the soil, red into green, and another Robin springs up, to wear his jacket and bear a quiver of arrows at his back.

Remember Henry dressed as a Turk? The king loves to dress up. In Wolf Hall, we encountered Anne Boleyn as Maid Marion, while Henry played at being an outlaw in the Greenwood. In 1510, he surprised his first wife Katherine by appearing in disguise as Robin Hood. Perhaps the merry rebel made him feel free, a role reversal of life at court? Henry’s green sleeves are waiting in his wardrobe for one final fateful outing.

Mantel ties Cromwell’s thoughts on Robin Hood to a new play he is commissioning about Thomas Becket: ‘Old stories can be rewritten. It is good to get such personages harnessed in the king’s cause.’ Only a few months ago, Jane Seymour was asking to visit Becket’s shrine at Canterbury. But Jane is now dead, and Cromwell is making an iconoclastic push against the saints and idols of old England:

‘Could you, he asks, write a play about the villainous Archbishop Becket, who defied his king? About the sorry end he came to, knocked on the head like a calf by four stout and loyal knights?’

I wrote about Thomas Becket’s story way back in Week 2 of Wolf Crawl. We will meet his bones later in our story.

Further reading:

4. Christina of Denmark

The Duchess Christina is at the court in Brussels, with her aunt, who is regent in those parts for her brother the Emperor. Early in March, he commissions Hans to go out with Hoby and paint her. On 12 March, Hans is granted a three-hour sitting. 'I think,' Henry says, when he sees the drawing, 'that we might have a little music tonight.'

Thomas Wolsey had originally tried to get Christina wed to Henry’s illegitimate son FitzRoy. The Duke of Richmond is now dead; and so is Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan.

The sixteen-year-old Christina did not hide how she felt about being married to the King of England: she sat for Hans Holbein in full mourning dress in a room hung with black velvet, black damask and a black cloth-of-estate. She supposedly said: ‘If I had two heads, one should be at the King of England's disposal.’

She had good reason to be wary. Katherine of Aragon was Christina’s great-aunt. Her uncle, Emperor Charles, may have entertained the idea of a political alliance with England, but the women in his family were understandably chilly about making another marriage with Henry Tudor. Christina was a favourite of her aunt, Mary of Hungary, who also opposed the match. In 1539, Christina fell in love with René of Chalon, Prince of Orange. More oranges! In the end, she would make a political match with the Duke of Lorraine in 1541.

But the council says, if a king makes a love-match once in his life, count him lucky. He can't expect to do it again and again.

The challenge Cromwell and the council face is that Henry is not especially disposed to political marriages. He believes he should love his wives. And among sixteenth-century nobility, this is a rather peculiar position to take.

Further resources:

5. The London wizards

The London wizards bear a grudge against Lord Cromwell, and no wonder. He has watched them since the cardinal’s death. He has confiscated their alembics and retorts, their snakeskins and secret bottles containing homunculi, their orbs and robes and wands. He has impounded their Clavicula Salomonis for calling up the dead, and read their texts in mirror writing; he has tossed to his code-breakers their almanacs in unknown tongues. Anyone who wishes may open his chests and inspect their cloaks of invisibility: which they claim he has converted to his own use.

Hilary Mantel is always playing with Cromwell’s proximity to magic. On the one hand, he is the modern sceptic and the enemy of all superstition. But like the cardinal before him, people suspect he must practice his own dark arts to have amassed so much power over a king and his country. Sometimes he encourages the idea.

Alembics and retorts are vessels used in chemistry. Clavicula Salomonis, The Key of Solomon was a treatise on magic attributed to King Solomon. Homunculi were reputedly miniature humans that could be artificially created in an alchemist’s workshop. Cromwell is indeed keeping a close eye on the wizards; the term homunculus was first used by the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. In his 1537 De natura rerum (“On the nature of things”) he explained how to make one:

That the sperm of a man be putrefied by itself in a sealed cucurbit for forty days with the highest degree of putrefaction in a horse’s womb, or at least so long that it comes to life and moves itself, and stirs, which is easily observed. After this time, it will look somewhat like a man, but transparent, without a body. If, after this, it be fed wisely with the Arcanum of human blood, and be nourished for up to forty weeks, and be kept in the even heat of the horse's womb, a living human child grows therefrom, with all its members like another child, which is born of a woman, but much smaller.

6. Burnings

Dry-eyed he watches, and watches everything. He does not steal one glance at the faces of his fellow councillors.

The climax of this chapter is a sequence of burnings. The Welsh saint Derfel fulfils the prophecy that he will burn a forest by being used as firewood at the execution of Katherine’s confessor, John Forrest. The Franciscan friar was burned for heresy in front of thousands of Londoners, including many evangelicals who had seen their own people burn at the hands of Thomas More and John Stokesley, Bishop of London. Was this revenge?

Hilary Mantel explores the idea by returning to Cromwell’s formative memory of the execution of the Lollard Joan Boughton. Mantel asks what witnessing such a death would do to a small boy lost in London:

It was years before he realised the boy who went to Smithfield was not the one who came home. The child Thomas still crouched under the stand, vigilant as the dogs, his hands cupped to catch the rain-water, the icy drops on his palm. It is a work he has never underaken, to go back and retrieve himself. He can see that small figure, at the wrong end of time; he can feel the heave of its ribs as it tries to cry without uttering. He can see and feel, without pitying the child; only suspect that, to keep the streets tidy, someone ought to collect it and send it home.

So striking that he, Cromwell, sees his former self as an ‘it’, a homunculus at the wrong end of time. This is one of two early traumatic events that Cromwell has trouble recollecting. The other has been hinted at in this chapter. But I will let you discover it for yourself.

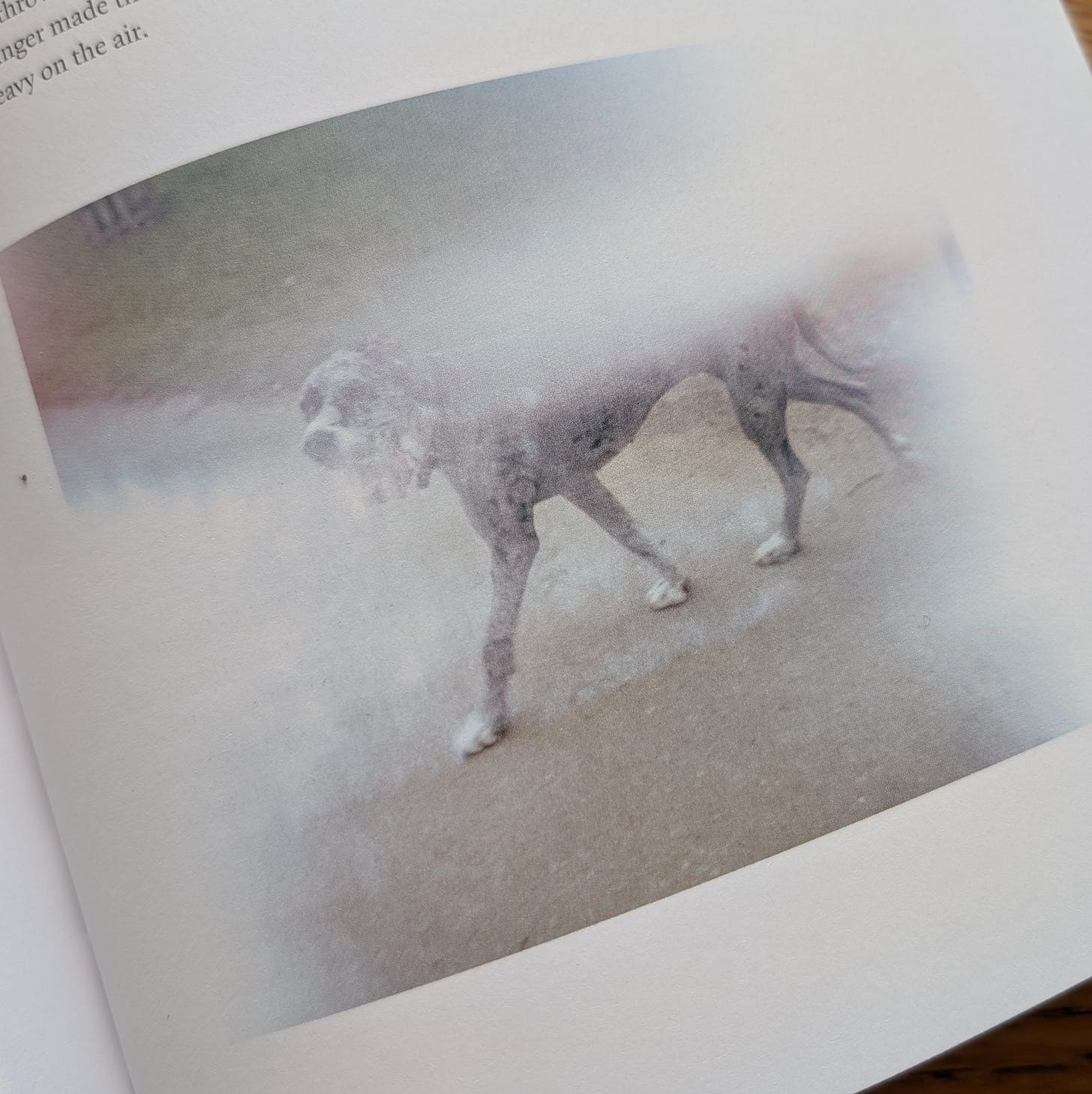

While writing The Mirror and the Light, Hilary Mantel collaborated with actor Ben Miles and his brother, photographer George Miles. They made images of modern London, looking for Cromwell’s shadow in the spaces he used to haunt. This photography is presented in The Wolf Hall Picture Book with quotes from the trilogy.

One image is an overexposed photograph taken by George Miles of a ghost-like dog on the streets of London. Hilary Mantel writes:

Wolf Hall includes an imagined scene in which the child Cromwell witnessed the burning of an old woman. One element was missing from that memory, which this picture supplied, and which is added when Cromwell remembers the event in the third book.

These dogs have no ‘name, kennel nor master’. They have no religion, no political allegiance. They are hungry and he is just a boy.

The Lollard was lean pickings, no more fat on her than a needle. When they realised nothing was left but her smell, would they turn on him? Chunk of Putney flesh: one can bite out his throat and lick his blood.

His memories hunt him and haunt him and in each reflection, he sees his own death, repeated over and over. ‘One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.’

The circle tightened. At any sound they crouched, froze. But still they close in.

Further resources:

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the first half of ‘Corpus Christi, June–December 1538’. This runs from page 563 to 598 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “Wyatt has followed the Emperor from the shores of Spain to Nice…” It ends: “It’s not worth it. Nobody’s worth it.”

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Mirror and Light really is all about memory. Cromwell turns back in his mind memories upon memories: his time with the cardinal, this Lollard burning, when he was married and his daughters were still alive. And everytime he does so, I get a little more worried. This book is like a slow boiling pot. The more we read, the more the tension rise. The higher Cromwell goes, the further he will fall.

You are right when you say it is so strange that Henry insists on a love match. I wonder why that is.

It's fascinating that there are two instances up to this point where Henry has almost died, and yet we are slowly creeping to Cromwell's death. "Nothing protects you, nothing. In the last ditch, not rank, nor kin. Nothing between you and the fire." Mantel is foreshadowing Cromwell's death in so many ways, it's astonishing.

How the specter of Death looms in this chapter. Crumb continues to crush the King's enemies at home, but this is not what Henry really wants. Cardinal Pole is rendered invulnerable to Cromwell's machinations by his own stupid incompetency and the king's disappointment is palpable. Meanwhile, Bishop Gardiner (himself, largely incompetent) looms ever closer. Henry will not kill you for incompetence, but we dare not disappoint. The more Cromwell accomplishes for his king, the more his king expects from him. Lately each chapter seems better than the last, the same can be said for your posts, Simon. Cheers!