Welcome to week seventeen of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 2 Part 3 Chapters 10 – 16. Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. And until the end of April, I am running a flash sale on annual subscriptions. Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s tangent: The colour of the soul

I wrote this piece during my 2023 slow read of War and Peace.

‘And in my dream I knew that these drawings represented the love adventures of the soul with its beloved.’

– Pierre Bezukhov

This week, I fell in love again. With Pierre, Andrei, Natasha and the world.

I dreamed a dream, a song of songs, the book of books, the colours in my soul.

There are notebooks in the attic, diaries in the drawer: words for no one but myself. My shadows, writing back the years.

The years when I first saw you. The years when we first danced. How I dared to risk it all for misery or joy. How I dared to love you, though I didn't know you then. How I dared to love the world, in the dark before the dawn.

If you read what I wrote then, if you dreamed my dreams. You'd say it all was nonsense and it didn't mean a thing. You'd say I was delusional, a fantasist, unhinged. I heard music in the silences and saw colours in the soul.

But believe me when I tell you: that this is how it starts. To love you must imagine, you must step into the dark. You must risk reality against the weirdness of the heart. Its crooked stair, its narrow plank, its leap before you look.

There is a clock in my father's house: it's narrow, it's light grey. It chimes the hour, every hour, time never runs away. It will never stop, it will never break. Never love or hate.

But long before the clockwork men and the great reformers with their talk, we told the time by the sky above, we read the heaven's thoughts. The mysteries of the firmament: The stars, the sun, the moon.

Her soul was cobalt blue. His soul was lilac green.

And up there, the dance began – the universal waltz. The wine of our first love. The light we waited for so long.

In the end, we didn't need the clockwork men, nor their clever talk. We had each other then, and then. And then we had the world.

So believe me when I tell you, that this is how it starts. To love, you must imagine, you must step into the dark.

Chapter 10: The labyrinth of lies

Pierre keeps a diary, documenting the strivings of a lonely and tormented soul. He admits Boris into the Brotherhood while harbouring murderous urges towards him. His dreams are a maze of fantasy and longing: he is attacked by dogs of passion and lies down with a young Bazdeev. He draws the Song of Songs as a maiden and feels he is doing wrong.

Have you ever kept a dream diary?

What do you make of Pierre’s dreams?

In Yiyun Li’s Tolstoy Together, Olivia Wolgang-Smith writes:

Pierre’s diary entries are so heartbreaking. Usually Tolstoy’s narration gives the reader a kind of protective, loving, even sometimes humorous distance from his pain and confusion—one I only appreciated when this epistolary section stripped that distance.

This is one of my favourite chapters in War and Peace, and it is also one of the weirdest. We wouldn’t want 1,000 pages of Pierre’s inner turmoil, but for one brief moment, Tolstoy nudges open the cellar door and gives us a frightening glimpse of the dark shapes moving down below. He is clearly depressed and anxious and lost. But it ends on a rather glorious transcendent image of the Song of Songs in human form. Like so many of my own dreams, I don’t know what to make of it. And neither does Pierre:

And in my dream I knew that these drawings represented the love adventures of the soul with its beloved. And on its pages I saw a beautiful representation of a maiden in transparent garments and with a transparent body, flying up to the clouds. And I seemed to know that this maiden was nothing else than a representation of the Song of Songs.

Tangent: Love adventures of the soul

The Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon, is an ancient erotic love poem. It is unique in the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament in its celebration of human love and physical desire, without reference to God’s law or the relationship between men and God. It is one of the most beloved pieces of scripture and it has inspired art and music and literature. Here is it awakening something in Pierre.

Pierre feels he is doing wrong, and indeed, his Freemason guides seem to be encouraging this disquiet in him. But I don’t think he is doing wrong. I see these “love adventures of the soul” as representing Pierre’s love of life: something greater beyond the “labyrinth of lies” where he has found himself. To my mind, his dream is telling him to listen to his heart. But he remains too frightened to do so.

Chapter 11: Berg on business

As the Rostov finances go from bad to worse, the old count heads to Petersburg with his daughters. Berg bores everyone with his war stories. He uses his “good-natured egotism” to convince the Rostovs that he is an excellent match for Vera, whom they are ashamed of not loving quite so much. Berg presses the count for a dowry, and an embarrassed Ilya Rostov haggles the wrong way, landing the groom with an extra 20k the Rostovs don’t have and can’t afford.

Ilya Rostov • Vera • Berg

Footnote: The Finnish War

In the Finnish war [Berg] also managed to distinguish himself. He had picked up the scrap of a grenade that had killed an aide-de-camp standing near the commander-in-chief, and had taken it to his commander. Just as he had done after Austerlitz, he related this occurance at such length and so insistently that everyone again believed it had been necessary to do this, and he received two decorations for the Finnish war also. In 1809 he was a captain in the Guards, wore medals, and held some special lucrative posts in Petersburg.

At Tilsit, Russia and France ended hostilities and formed an alliance against Britain. The treaty was designed to impose the Continental System on mainland Europe, an embargo on all trade with Britain. Sweden’s refusal to comply became the pretext for a Russian invasion of Finland, which then remained part of the Russian Empire until 1917.

At first it seemed strange that the son of an obscure Livonian gentleman should propose marriage to a Countess Rostova; but Berg’s chief characteristic was such a naive and good-natured egotism that the Rostovs involtunarily came to think it would be a good thing, since he himself was so firmly convinced that it was good, indeed excellent.

What do you think Tolstoy means by ‘good-natured egotism’, and have you ever met anyone like Berg?

Chapter 12: Life in prose

Natasha is tormented by a promise she prised out of Boris four years ago. Boris has been living his life in prose, in his colourless climb up the social ladder. But Natasha is “his most poetic recollection”, and when he goes to visit the Rostovs, he is “disturbed and confused” by a much-changed Natasha. Against his better judgement, he keeps returning, spending whole days with the Rostovs. A neglected Hélène sends him reproachful notes every day.

Natasha • Boris • Countess Rostova • Hélène

Tangent: The clockwork man

Boris’s uniform, spurs, tie, and the way his hair was brushed, were all comme il faut and in the latest fashion. This Natasha noticed at once. He sat rather sideways in the armchair next to the countess, arranging with his right hand the cleanest of gloves that fitted his left hand like a skin, and he spoke with a particularly refined compression of his lips about the amusements of the highest Petersburg society, recalling with mild irony old times in Moscow and Moscow acquaintances.

Notice again how Tolstoy uses Moscow and Petersburg as shorthand for two opposing ways of being in the world: Boris has put away childish things and become a well-respected man of Petersburg society.

Later in life, Tolstoy wrote a novella called The Death of Ivan Ilyich about a man facing his own death and coming to terms with the fact that he has never lived. In his lecture on this novella, Andrew Kaufman argues that Boris Drubetskoy is an early blueprint for Ivan Ilyich. He demonstrates the hazards of a life lived conventionally with a focus only on the appearance of things: the spotless uniform and the cleanest gloves.

In contrast, Natasha embodies something wild and volcanic in human nature. Marya Dmitrievna called her the cossack. Berg thinks her “unpleasant.” Her vitality transfixed Denisov and made him do stupid things. Now, she has “disturbed and confused” Boris, compelling him to act despite himself and to live once again, if only briefly on borrowed time.

When have you resolved to do one thing, only to have instead followed your heart?

What is the difference between the worldviews of Berg and Boris?

Chapter 13: The colour of the soul

The two Natashas (mother and daughter) talk in bed. The mother worries about her daughter’s honour and future marriage prospects if she continues to flirt with Boris. Natasha says it does not have to be for love and marriage, ‘but just so’. She describes the colours and shapes of Boris and Pierre's souls. Her mother and Sonya wouldn’t understand, she thinks. She dreams of being admired and then falls asleep, ‘where everything was as light and beautiful as in reality, and even more so because it was different.’ The next day, her mother tells Boris to stop visiting the Rostovs.

Natasha • Countess Rostova • Boris

Tangent: The limits of language

In the chat, there is plenty of discussion about whether Natasha has synesthesia. Maybe, but I think far more interesting is how she is pushing against the limits of language and how we describe the world. Many of us have done this, especially at that young age, when words seem to fail to capture the depth and breadth of our feelings. Let us now talk of love and marriage, we are happy and things are “just so.” Boris is a light-grey clock, Pierre is a red and blue square.

What colours and shapes would you use to describe other characters in War and Peace?

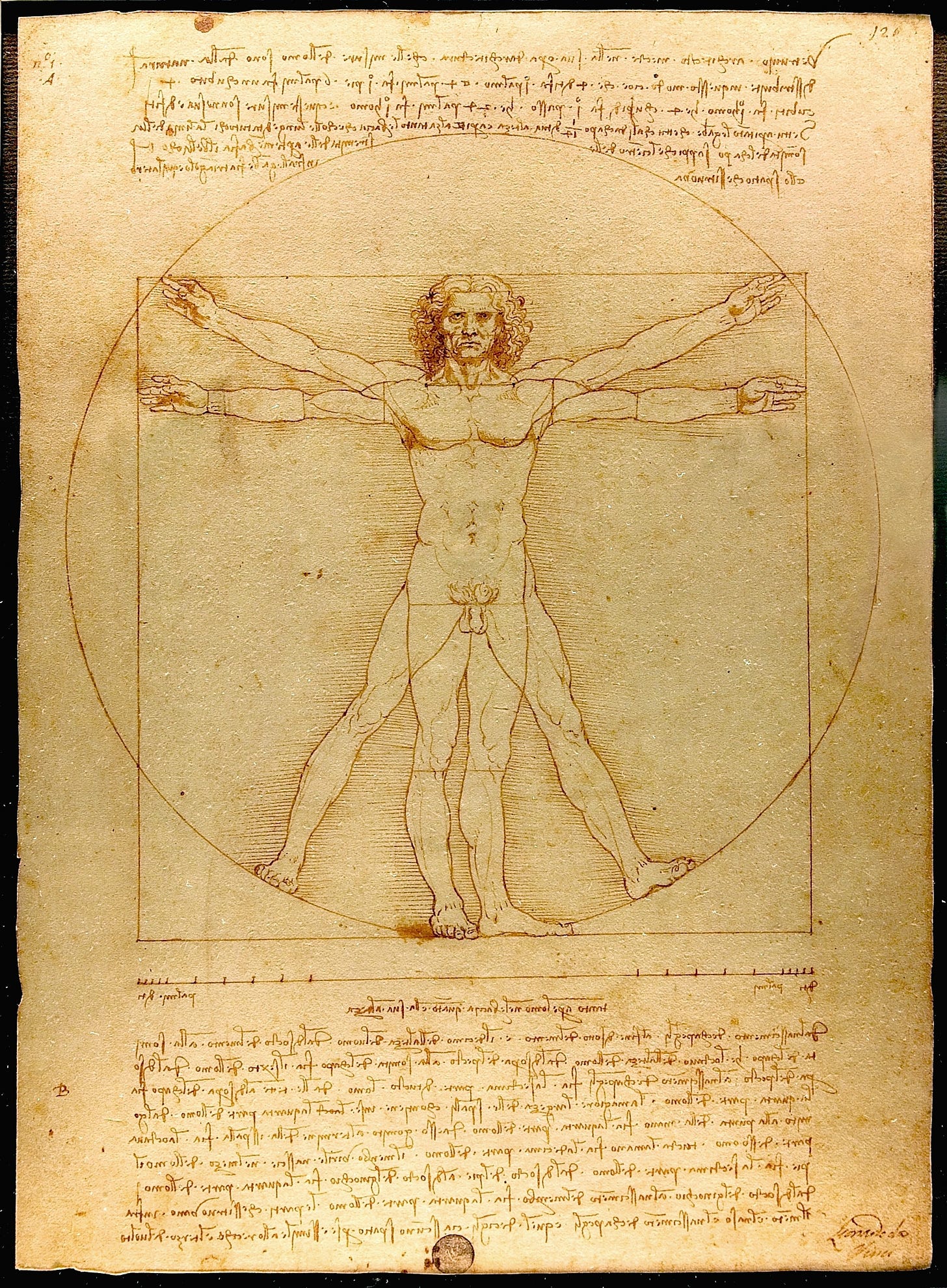

Square Pierre is interesting since only a few chapters ago, he was trying to grasp the mysteries of the square and its importance to Freemasonry. The square also recalls the ideal bodily proportions of the Vitruvian Man in Leonardo da Vinci's notebook sketch. Thank you

and for spotting these particular tangents.Tangent: The lives of Countess Rostova

'I'll tell you some things about myself. I had a cousin... 'I know! Kiril Matveich... but he's an old man.' 'He was not always old.'

Part of the art of fiction is showing the tip of the iceberg and letting us imagine what lies below. In three lines, Tolstoy makes us wonder again about the past lives of Countess Rostova. We know Prince Vasili once courted her, and her giggling in this chapter reveals a softer version of herself that is more like Natasha. I would love to read her backstory because I think there is so much more to this woman than we ever see in War and Peace.

What do you think she was like in her youth? Can you invent a story for her?

Chapter 14: You shall go to the ball

It is New Year’s Eve, 1809, and Natasha is going to her first ball. She’s been up since eight getting everyone dressed, but it is ten in the evening, and they are still not ready. The delay is mostly caused by Natasha’s dress, which is too long. The resourceful Dunyasha comes to the rescue with needle and thread. The count and the countess don their glad rags, and then we are all, finally, off to the ball.

Natasha • Sonya • Countess Rostova • Count Rostov

Tangent: An older love

Following on from the last chapter, I enjoyed reading the count complimenting his wife as she “came in shyly, in her cap and velvet gown.” In a book full of youthful expressions of love, lust and infatuation, the Rostovs are a rare example of the love between a couple growing old together.

Footnote: The English Embankment

The ball and midnight supper are being held at a mansion on the fashionable English Embankment. This street was where the British Embassy and English Church were originally located. In 1917, it was from these quays that the Battleship Aurora fired the shot to signal the storming of the Winter Palace during the Russian Revolution.

It was already five minutes to ten and the girls were not yet dressed.

This chapter reminds me of the times when it was considered rude to turn up at a party before 9 PM. These nights, I am tucked up before ten, ready to be up with my children before six.

How about you: are you normally the first to arrive, bang on time, or always late?

Chapter 15: Beauty and the Buffoon

We see the ballroom from Natasha’s eyes, her heart racing and her reflection blurred into “one brilliant procession.” The elderly Peronskaya points out the most important people there, including Hélène and her husband, the universal Freemason Pierre Bezukhov. He is on his way to introduce Natasha to dancing partners but stops to talk to Andrei. “Too proud for anything,” says Peronskaya of Andrei. They are the only two men she dislikes, and the only two noticed by Natasha.

Natasha • Sonya • Anatole • Hélène • Andrei • Pierre

Footnote: Marya Antonovna

'Ah, here she is, the Tsaritsa of Petersburg, Countess Bezukhova,' said Personskaya, indicating Hélène who had just entered. 'How lovely! She is quite equal to Marya Antonovna. See how the men, young and old, pay court to her. Beautiful and clever...'

Hélène is compared very favourably to Marya Antonovna, Tsar Alexander’s mistress. Their relationship lasted 18 years and she had four illegitimate daughters by Alexander. She tried to persuade him to divorce Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna, but he eventually left Marya Antonovna to return to his wife in 1818.

Chapter 16: Take this waltz

The Emperor enters, and the guests dance the polonaise. Natasha fears no one will ask her to dance – Boris turns away twice, and Anatole looks at her “as one looks at a wall.” She is left chatting with Berg and Vera, who, of course, don’t dance. Then Pierre approaches an “animated and bright” Andrei and introduces him to Natasha. We learn that Andrei not only likes dancing but is good at it. And when he dances with Natasha, the “wine of her charm” goes straight to his head.

Natasha • Andrei • Pierre • Vera • Berg • Boris • Anatole • Hélène • Sonya • Countess Rostova

Footnote: Let’s dance!

As the name suggests, the polonaise is one of the five historic national dances of Poland. One of the others is the Mazurka, which we have already encountered thanks to Denisov. The polonaise was popular at the French court and across Europe and was usually the first dance at a ball. In Polish, it is called “the walking dance”:

The waltz evolved in the late eighteenth century from a German folk dance and became all the rage at the Austrian court in Vienna. The word comes from the German to revolve or turn about, and at first was considered scandalous for the face-to-face position of the dancers and the “mad whirl” so different from stately formal dancing. It was the first dance that allowed the man to hold the woman’s waist. No wonder, Andrei is electrified:

… but scarely had he embraced that slender supple figure, and felt her stirring so close to him and smiling so near him, than the wine of her charm rose to his head, and he felt himself revived and rejuvenated when after leaving her he stood breathing deeply and watching the other dancers.

“Never have I moved so lightly. I was no longer a human being. To hold the most adorable creature in one’s arms and fly around with her like the wind, so that everything around us fades away.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

And here is the iconic scene in the BBC adaptation. Warning: it contains mild spoilers for the next few chapters:

Tangent: Dreams and nightmares

And before Dunyasha had left the room [Natasha} had already passed into another yet happier world of dreams, where everything was as light and beautiful as in reality, and even more so because it was different.

This week took us from Pierre’s nightmares to Natasha’s dreams. Whatever we think of Pierre, or Andrei or Natasha… whatever we think about their suitability for one another, their naivety and their self-delusion, we can meet them on the common ground of these dreams and fears. In seven chapters, Tolstoy shows us the depths of depression, the intimacy between mother and daughter, and the anxiety and excitement of your first ball and your first dance. Here is the richness of life in all its joys and misery. Here is the waltz of the world, “the love adventures of the soul with its beloved.”

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. And to celebrate completing Wolf Hall this week, I am offering a flash sale of 25% off for annual subscriptions:

You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

No wonder the waltz was seen as thrilling. The Polonaise looks deathly dull by comparison!

The beautiful dance even thawed my icy old heart a bit. Never could dance a step well but I could while watching this video. Thanks @Simon Haisell for sharing it.