The house of love and ruin

War and Peace Week 12: Book 2 Part 1 Chapter 12 – Part 2 Chapter 2

Welcome to week twelve of War and Peace 2024. This week, we read Book 2 Part 1 Chapter 12 – Part 2 Chapter 2. Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These posts are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Thank you for your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

The week’s theme: The house of love and ruin

May you be born a Rostov.

May you be loved. And born into love. May you know happiness from first breath to last. And never hear cruel words spoken.

In this house, joy is everything. It is in the air, and the food and the music. It is a drug, a spell, an enchantment.

If you are a guest – like little Denisov – you will be bewitched. Joy will overflow. And move your feet and move your heart. You'll compose verse and dance and sing. You'll be the fool and fall in love and say so many stupid things. For love and joy.

The house of light guards its doors with an old magic. When demons and devils come knocking, the woodwork holds firm. Dolokhovs will not be admitted.

"I'll never marry," says Natasha, "but will be a dancer." The bright flame at the heart of the house. Like any fire, she cannot see the darkness, only the light she casts.

Wounded devils drag themselves away. From the duelling ground and the drawing room, to some dark hole. Between two candles, where a demon shuffles the deck and lays down the cards.

"None but fools trust to luck in play."

May you be born a Rostov.

A little Nikolushka in his crib. Breathing joy and love and happiness. As other poor souls breathe air and sorrow and hate. So natural to him is happiness that he cannot see the darkness. On the battlefield it is unthinkable that anyone would want to hurt him.

"To kill me? Me who everybody loves."

Now his friend sits across from him, cold face and red hands, deciding his fate. Designing this boy's ruin and the family too. The ruin of the house of joy.

Down in the hole, separated from the light, little Nikolushka sees everything now. As though for the first time: "I did not realize how happy I was!"

For he was so happy he did not know how lucky it is to be a beloved brother, a son, a friend. And he will be different now. He will forgo the cards and the drink and fill his sister's album with verse. He will hold onto her voice as it rises. "This is real."

But the music stops. The bubble bursts. The spell is broken. And ruin has come to the house of love and joy.

Chapter 12: Dancing Denisov

Natasha, Nikolai, Sonya and Denisov go to Iogel’s ball. And they have a fabulous time. Sonya glows with pride for Dolokhov’s proposal and her refusal. Natasha is in love with everyone. Denisov is spellbound by Natasha, and once he is coaxed into dancing the mazurka, he enchants everyone, and the old men begin to talk about the good old days.

Sonya • Natasha • Nikolai • Denisov

Footnote: The mazurka

Dance plays a key part in War and Peace. We have already seen Count Rostov’s Daniel Cooper, now here is Denisov with the Polish mazurka. Tolstoy describes the dance as “newly introduced” to Moscow, a souvenir from Russian imperialism in neighbouring Poland (see below). The dance master Iogel has clearly tried to restrain and domesticate this folk dance, much to the impatience of Vaska the cat.

Learn more about the mazurka in this short video:

And this is what the nineteenth-century German dance master Friedrich Albert Zorn wrote about the mazurka:

The Mazurka is, beyond question, the most beautiful social dance of our time, and I know, from more than fifty years of experience, that everyone who has learned the dance prefers it to all others. The Mazurka is a combination of exaltation, boldness, knightly gallantry and the most graceful devotedness. There is in this dance a certain inspiration not to be found in any other. Nearly every Mazurka dancer feels an incredible sensation entering his very soul and driving away all fatigue, the moment the strains of Mazurka music fall upon his ear.

Footnote: The good old days

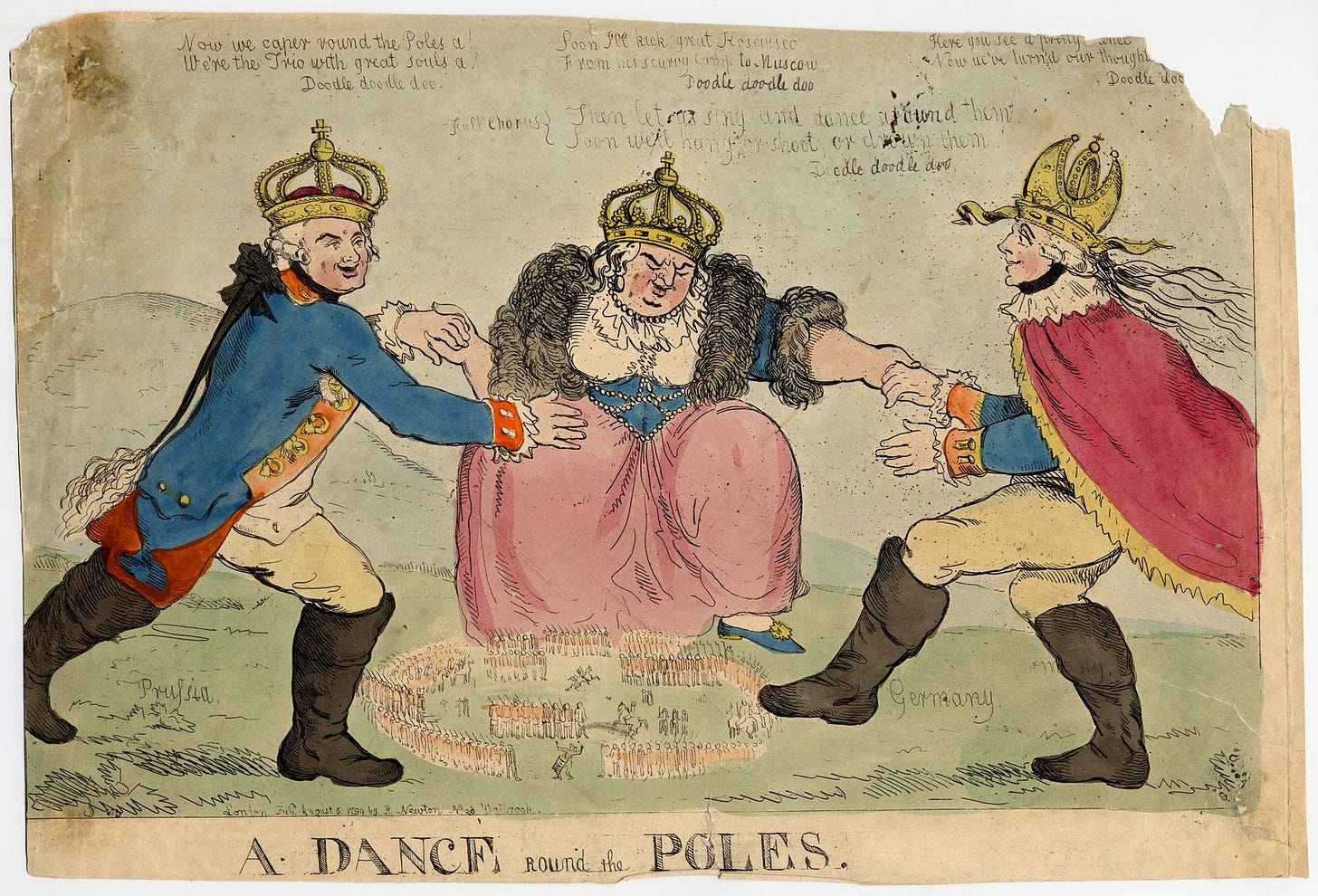

There’s a sinister footnote at the end of this chapter. While the young dance, “the old men began smilingly to talk about Poland and the good old days.” Tolstoy doesn’t elaborate, but these men probably fought in Poland under General Suvorov during Catherine the Great's reign. Between 1772 and 1795, three partitions of Poland carved up the country between the empires of Russia, Austria and Prussia. Poland remained under partition until 1918.

Chapter 13: Don’t ruin yourself

After Sonya’s rejection, Dolokhov stays away from the Rostovs. Then, before leaving to join his regiment, he invites Nikolai to a farewell feast. There, between two candles, he challenges Rostov to cards. “Or are you afraid of me?” he asks as the stakes get higher. On the fate of a seven of hearts, the young Count Rostov watches his “newly appreciated and newly illuminated” happiness plunge into misery.

Nikolai • Dolokhov • Ilya Rostov

Beneath his smile Rostov saw in [Dolokhov] the mood he had shown at the Club dinner and at other times, when as if tired of everyday life he had felt a need to escape from it by some strange, and usually cruel, action.

Tangent: Strange cruelty

Why did Dolokhov challenge Pierre? This chapter makes me consider two possibilities. One is that Dolokhov, the warrior, finds it very difficult to adapt to civilian life, which leads him to take risks with other people’s lives and his own. The other theory is that Hélène rejected him. He responds to Sonya’s refusal with adolescent vindictiveness. For those of us who maintain that Hélène was faithful to Pierre, here is some evidence that Dolokhov acted from jealousy and out of revenge.

Footnote: Gamblers and cheats

Dolokhov is based on Tolstoy’s relative, Fyodor Tolstoy, “The American.” A notorious cardsharp, he was known to say, “only fools rely on luck,” almost the same motto that Dolokhov brings to his game with Nikolai. Dolokhov even boasts about rumours that he is a cheat. But Nikolai is too afraid to challenge him on the matter.

Leo Tolstoy inherited his own gambling addiction from his grandfather (Ilya Tolstoy, the blueprint for Ilya Rostov). It appears to have been a common affliction among Russian writers. Alexander Pushkin wrote the classic gambling story The Queen of Spades and gambled away his own manuscripts in a game of cards. Dostoyevsky, author of the novella The Gambler, was also a compulsive gambler who on one occasion bet and lost everything he owned.

The game Nikolai and Dolokhov are playing is faro, popular among nineteenth-century gamblers before the advent of poker. You can learn how to play here. Please gamble responsibly.

Chapter 14: The rupture

The card game continues, but it is no game. Rostov mounts up a forty-three thousand rouble debt, to be paid tomorrow to the man with the red hands. “When did it begin?” Rostov asks himself as he tries to pinpoint the moment he slipped from happiness to misery. “And I did not realize how happy I was!” he thinks. Dolokhov makes it clear what this is about: Lucky in love, unlucky in cards. “Your cousin is in love with you.”

Losing at the card game gives Nikolai the same epiphany as the lofty sky gives Prince Andrei, though being destroyed slowly by a friend is a hundred times more terrifying than dying on the battleground.

— Yiyun Li in Tolstoy Together

Do you agree?

Tangent: Breaking points

Tolstoy prepares the precise and appropriate breaking point for each of his characters. Andrei almost died to learn that he had never lived. Pierre was forced to act on the duelling ground, to discover all his actions and inaction so far in life have been folly. Nikolai betrays his family’s trust and love by being betrayed by a man he believed loved him. In doing so, he discovers he never really knew how happy he was and how much he was loved. Epiphanies can be found in lofty skies. Or in dark holes.

Footnote: Tolstoy the gambler

On 28 January 1855, Tolstoy sat down for a game of cards. He was stationed at a village near the Belbek River in Crimea, with a senior officer called Odakhovsky who had a reputation for cheating at cards. That evening, Tolstoy lost six thousand rubles and was forced to sell the house he was born in to pay the debt. His home, with its three stories and forty-two rooms, was dismantled, hauled away, and rebuilt on a neighbour’s estate, eleven miles away.

The loss plunged him into emotional turmoil. There were moments of enlightenment, writing in his diary his intention to start a new religion. And moments of self-hatred, scribbling down that “It’s amazing how loathsome I am, how altogether unhappy and repulsive to myself.” And, of course, he continued to gamble.

Chapter 15: Face the music

Nikolai returns home to the house of joy. Denisov is composing a song, and everyone is coaxing Natasha to sing. So intense are their feelings that sister and brother cannot comprehend or conceive of each other’s happiness or misery. But when Natasha begins to sing, the finest part of Rostov’s soul is moved into a moment apart and above everything in the world. “This is real.” If only it could last forever.

Nikolai • Natasha • Denisov • Sonya • Vera • Shinshin • Countesss Rostova

Tangent: Gaining a wider perspective

This episode is explored at length by Andrew Kaufman in Give War and Peace A Chance: Tolstoyan Wisdom for Troubled Times. In the chapter “Rupture”, Kaufman discusses how Rostov’s experiences on the battlefield and at cards force him to widen his perspective and see the world differently. The Rostov family name comes from the verb rosti, “to grow”, and in this chapter he grows, choosing not to put a gun to his head, but to fill his lungs and sing. Kaufman is worth quoting at length:

What [Tolstoy] is showing is that in this moment of emotional crisis Nikolai taps into a reality larger than himself. This swashbuckling young man who only a day earlier was on top of the world, and more recently has come to feel the weight of the world bearing down upon him, suddenly senses that there is something in life that is bigger than his own ups and downs, his narrow concepts of himself, or his familiar frameworks of understanding. Nastasha’s irrational joy infects him now, and just as mysteriously as his life had been transformed only hours earlier—undeniably for the worse, it seemed to him—so is Nikolai suddenly transported again, only this time to a state of momentary bliss.

Had he not lost forty-three thousand rubles, had his world not just been turned on its head, would he have been able to hear the full beauty of his sister’s voice? Surely not. Tumultuous times, Tolstoy tells us, can jar us into heightened awareness, expanding our sense of both ourselves and life’s possibility. Losing something valuable, that is, we gain in return something invaluable: a radically widened perspective.

Chapter 16: Explaining Nonsense

Nikolai tells his father about the forty-three thousand. “Nonsense,” says Ilya Rostov. Nikolai is ashamed of how he tries to make it seem like nothing, and his father’s flustered acquiescence makes it even worse. Natasha tells her mother that Denisov has proposed to her. “Nonsense,” says the countess. Natasha said it happened accidentally and Denisov says “I have done w’ong.” Nikolai spends the next two weeks with Sonya and Natasha, pays Dolokhov and then joins his regiment in Poland.

Nikolai • Natasha • Denisov • Countesss Rostova • Sonya • Ilya Rostov

Footnote: How much is 43 thousand rubles?

It is difficult to convert historical currencies into today’s money. I have seen 43,000 rubles in 1806 calculated as anywhere between 321,000 and 1,2500,000 dollars. Perhaps a better reference point is one of Nikolai’s horses, purchased earlier in the novel for 1,000 rubles. Forty-three fine horses might be the equivalent of 43 expensive cars. And it is over seven times greater than Tolstoy’s 1855 gambling debt that compelled him to sell his medium-sized country estate.

Whichever way you look at it, this is a serious amount of money, even for the Rostovs.

Tangent: Great and true storytelling

It’s interesting sharing this book with readers, a chapter a day, and seeing in real time people jotting down their expectations, hopes and fears about the chapters to come. “I’ll be angry if…”, “I only hope that…” Will Nikolai bargain away Sonya? Will he challenge Dolokhov to a duel? All these alternative plotlines fan out each day in our daily chat.

Of course, what Tolstoy does is far better than anything we can think of. We live through Nikolai’s initial state of shock and humiliation, his incomprehension of the happy life continuing on around him, his momentary bliss as Natasha’s voice allows him to forget himself, his involuntary blasé attempt to shrug off the debt, his instantaneous repulsion at his own words, and then the terrible realisation that his father is not going to punish him.

In the end, we don’t need any duels or dark bargains, and we don’t get a son cast out or a father losing his temper. No cheap tricks here, just great and true storytelling.

Congratulations on finishing Book 2 Part 1. Here is your next merit badge courtesy of

:Book Two, Part Two

Chapter 1: Delayed, for lack of horses

After leaving his wife in Moscow, Pierre set out to Petersburg. He is delayed at a post-station, where he finds himself asking life’s big questions: What do we live for? What is life, and what is death? Another man joins him: an ancient traveller with bright eyes who fixes him with a steady and severe gaze.

It was as if the thread of the chief screw which held his life together were stripped, so that the screw could not get in or out, but went on turning uselessly in the same place.

Tangent: Paperbacks in life’s waiting lounge

Madame de Souza was a popular French writer whose husband was guillotined during the Revolution. Confusingly, the book mentioned by Pierre is by another French writer, Sophie Cottin. Regardless, I couldn’t help but think of the cumulative hours spent worldwide in airports waiting for delayed flights. The cheap paperbacks bought in desperation and the many million existential questions asked while watching other people’s planes take off without you. There is nothing like waiting at a bus stop to make you ask, “What do we live for?”

Chapter 2: Look at your life

The stranger is Bazdeev, a freemason. Pierre tells him they are very different and will not understand one another. But Pierre hates his life and wants answers. The more Bazdeev speaks the greater is Pierre’s “sense of comfort, regeneration, and return to life.” On parting, Bazdeev tells him to seek out Count Willarski in Petersburg.

Bezdeev comes across as a bit of a spirituality peddler, not to mention a whack job. Still, he’s not a complete sham; there is something genuinely kind and attractive about him, not least when compared with those high-society vultures Pierre’s been moving among lately. Moreover, he gives Pierre something he badly needs in this moment: hope.

— Andrew Kaufman in Give War and Peace A Chance: Tolstoyan Wisdom for Troubled Times.

Footnote: The Freemasons

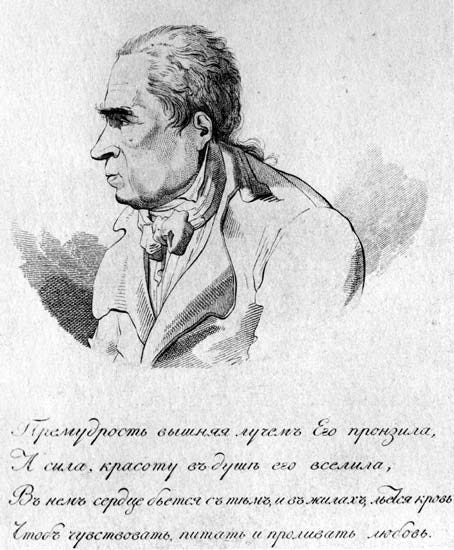

Bazdeev is loosely based on a leading freemason from this time, Osip Alekseevich Pozdeez. Freemasonry arrived in Russia around 1760 where it was suspected of political subversion and repressed during Catherine’s reign. Alexander I allowed secret societies to flourish before outlawing the Freemasons in 1822.

Before anyone asks, there is no evidence Leo Tolstoy was a Freemason. In 1866, he told his wife that researching their history for War and Peace put him in a “depression” and “all those Masons were fools.”

But we can talk more about the Freemasons and Pierre’s search for meaning next week.

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

This book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and have found it useful, please consider a paid subscription or put a few pennies in my tip jar on Stripe. Paying subscribers can read bonus reviews of all the parties in War and Peace and start their own threads in the chat area. Thank you for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

As always, the Sunday summary is enriching! Loved the videos and the artwork.

Honestly I think Pierre possibly becoming a Freemason is the biggest twist of this book. I think it really falls outside of my expectations for the scope of the book, and I’m so curious to see how Tolstoy uses it to develop Pierre’s character.