APOGS #3: Do you want a revolution?

Part Two, Chapter III. Maximilien: Life and Times and Chapter IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood.

For there comes the bald question, the one choice out of two: do you want a revolution, M. de Robespierre. Yes, damn you, damn all of you, I want it, we need it, that’s what we’re going to have.

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Two, Chapter III. Maximilien: Life and Times and Chapter IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can all be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

Last week, we followed the fortunes of Danton and Camille in Paris. This week, we catch up with Maximilien as he begins his legal career in Arras. He’s a dapper but otherwise dull provincial lawyer, a credit to the town, the abbot and his respectable family.

He lives with his brother Augustin and his sister Charlotte. He writes poems about jam tarts and fears that one day he may have to sentence a man to death. When that day comes, he will be sick in the street. Maximilien takes on cases against corruption, waives his fee and starts making ‘political speeches’ in court.

Meanwhile, Danton marries Gabrielle without telling her about his son and his debts. And Lucile decides to marry Camille and arranges matters without informing her husband-to-be.

It is the summer of 1787, the Paris Parlement is at loggerheads with the king, and the reformist aristocrat Hérault de Séchelles buttonholes two nobodies called Danton and Camille. They are astonished. And now at the Café de Foy, here is the actor Fabre d'Églantine, up on a chair.

‘All the right people are drifting together,’ Camille said. ‘You can pick them out, just as if they had crosses on their foreheads.’

The first riot of the revolution, and Camille is there. Danton is not. But Georges-Jacques feels it coming: “Twelve months from now, it seems to me, our lives will look very different.’

Meanwhile, the Duke of Orléans is being set up as a rival king, an enlightened Father of His People. The King confronts the Parlement, and Orléans stands up to his cousin. An Estates-General now appears inevitable.

Camille relates the proceedings to a crowd at the Café de Foy. Danton notices in the moment that Camille does not stutter, “and that he talked to every person in the crowded room as if he were speaking only to them.”

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then this week corresponds to episode 7. The Séance Royale.

King Louis XVI’s ministers have a package of reforms they need rubber-stamped by France’s 13 parlements – judicial organisations composed of the aristocratic First Estate. But the nobles aren’t playing ball, and the parlements are using this opportunity to exert their power. Some liberal voices call for an Estates-General of all three estates: nobles, clergy and commoners.

The standoff between the King and the Parlement of Paris leads to a small riot, the banishment of its members from the city, and the prominence of the king’s cousin, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans.

Footnotes

1. Ben Franklin and a lightning rod for revolution

Why would M. de Vissery want to attract lightning? Well, he was in league with the devil, wasn’t he?

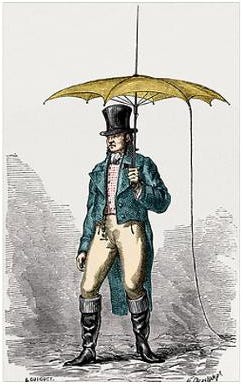

In 1752, the American polymath Benjamin Franklin proposed an experiment to conduct electricity from lightning using a kite. Franklin went on to invent a lightning rod to protect tall buildings. The invention has some curious spinoffs, including umbrellas and hats to protect individuals from bolts from above:

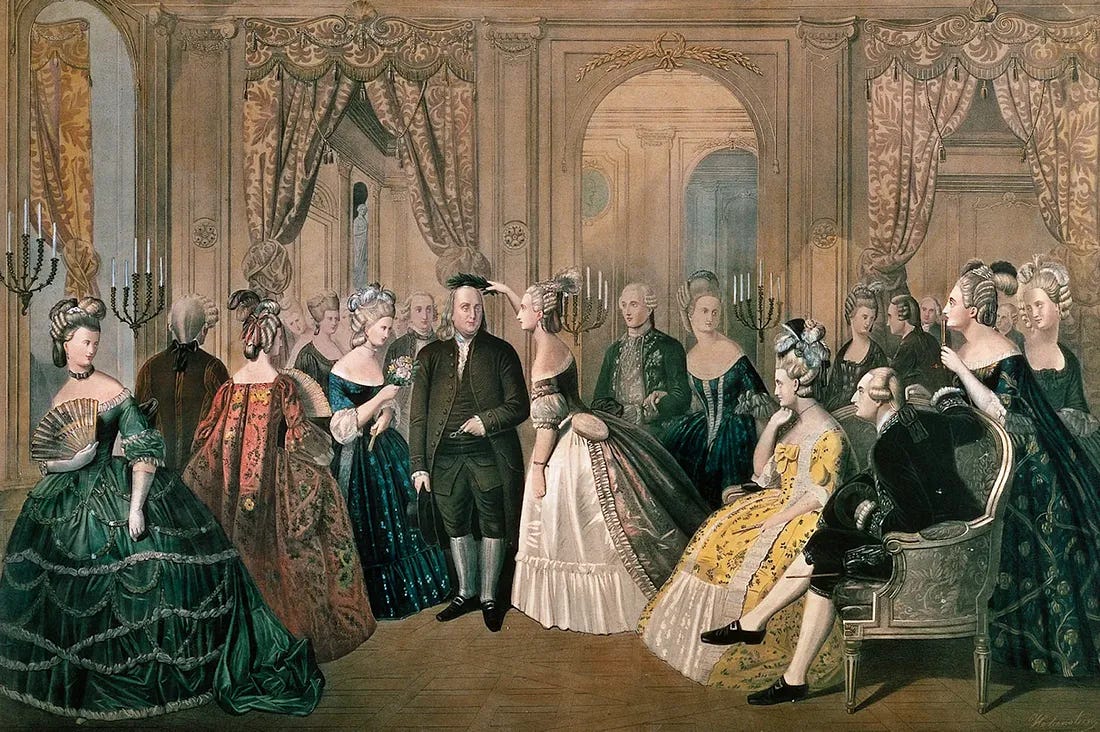

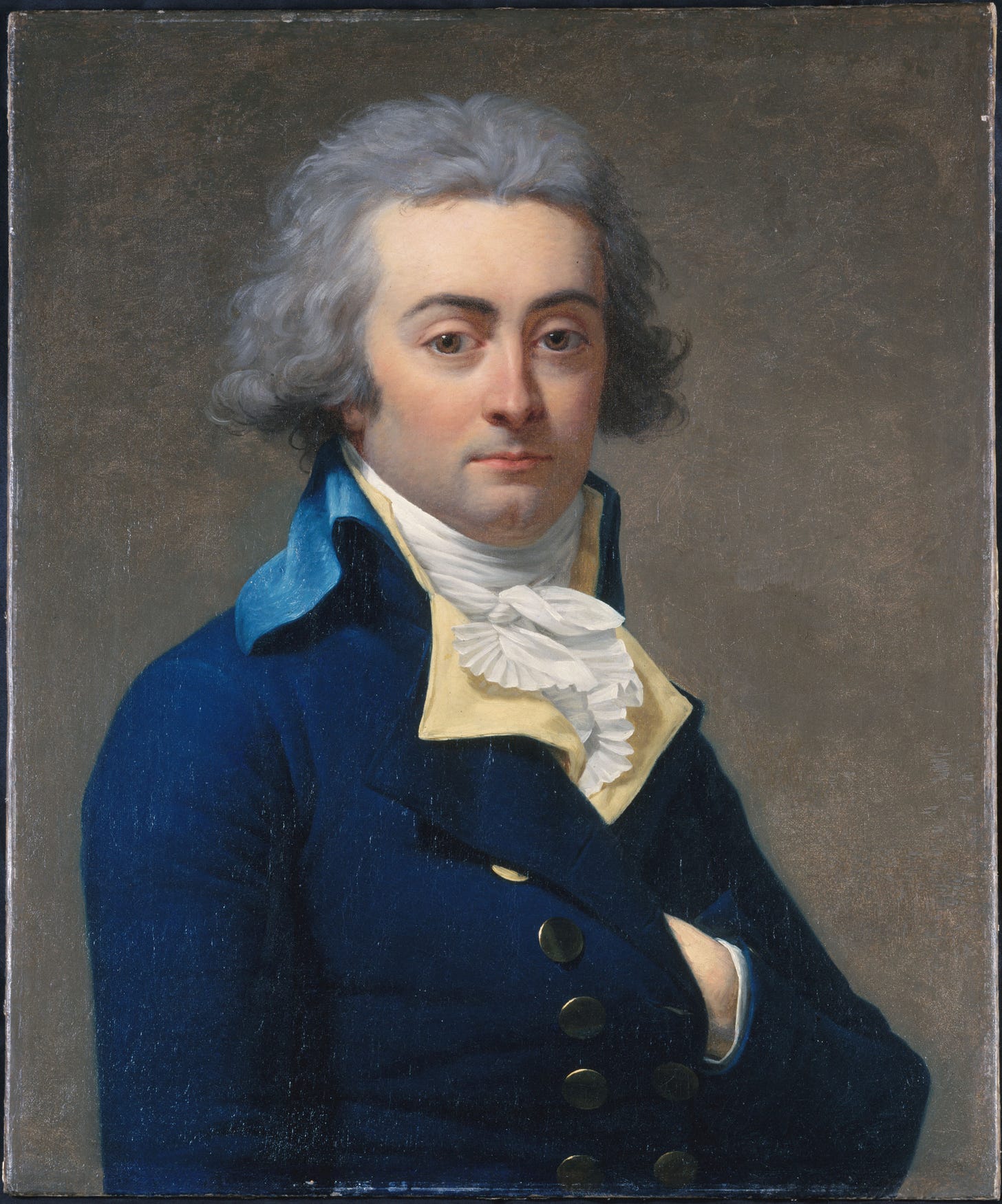

Franklin served as the first US ambassador to France, where the dressed-down diplomat stuck out in stark contrast to the elaborate costumes of the ancien régime:

“He seized the lightning from heaven and the sceptre from tyrants.”

— Anne Robert Jacques Turgot’s epigram of Benjamin Franklin

More: The Lawyer and the Lightning Rod (Historian Jessica Riskin)

Tangent: Struck with Style: Lightning Rod Fashion of the 18th Century

2. Brount

He lets Brount tow him through the streets, the woods, the fields; they come home looking not nearly so respectable as when they went out.

Robespierre’s doves from last week are apparently mentioned by his sister Charlotte in her memoirs. This may also be the source for Brount, Maxamilien’s “muddy dog” that Hilary Mantel makes a Great Dane. It doesn’t have to be a metaphor, but if it were, then Brount could be the angry mob Robespierre would later “lead” while doing his best to look respectable.

Animal-loving Max joins the great tradition of mass murderers who love their pets. Robespierre later notes that it is easy to put public safety before friendship because he doesn’t have any friends.

Then he thought, of course I have, I have Camille.

Shivers. A reminder that when they first met, Max was reminded of the dove in its cage, “soft and dead: little bones without pulse.”

Read: The 10 most famous dog-and-owner combinations in history (Country Life)

Read: 10 famous people in history and their bizarre pets (History Extra)

3. Ode to Jam Tarts

I give thee thanks who first with skillful hand Did fashion paste and pastry to command, And gave to mortals this delicious dish So nothing more was left for them to wish. Have they raised altars to thy glorious name, All consecrated to thy talents’ fame? Hundreds of lands are prodigal of vows The universe, its groves and temples, shows; But of thy genius they have little ken, Who brought Ambrosia on the earth to men Pies reign in honour at their festal board But thou’rt forgot as if by one accord.

That’s a translation of Max’s jam verse. You can read the original here.

Tangent: The short, sweet, and sticky history of jam (National Geographic)

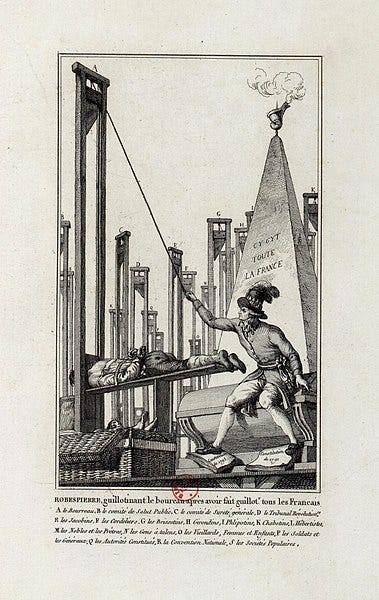

4. Robespierre and the death penalty

Today against his most deeply held convictions he has followed the course of the law and sentenced a criminal to death. And now he is going to pay for it.

It is a terrible irony that for most of his life, Robespierre was a vehement opponent of capital punishment. During the Revolution, he will call for its abolition.

5. My killers before they killed me

Two of the men Max meets in Arras will play a role in his destruction after the events of this novel are complete. For now, they are allies, “if not friends.”

Joseph Fouché, “with his frail, stick-like limbs,” proposes to Charlotte. Max is “a little overawed” by the captain of engineers, Lazare Carnot. Fouché will join the Jacobin club with Robespierre, and Carnot will sit on the Committee of Public Safety during the Terror.

Both men will work to overthrow Robespierre and later serve under Napoleon Bonaparte.

6. Louise-Félicité de Kéralio

Louise packed her bags and hurtled off into the future. He was dimly aware of a turning missed; one of those forks in the road, that you remember later when you are good and lost.

Louise-Félicité de Kéralio is another character who will return later. From minor Breton nobility, Kéralio will be very active during and after the Revolution. Not only was she the first “lady member” of the Académie of Arras, but she also joined the mostly male Cordeliers Club and became the first female editor of a journal, Le Journal d’État et du Citoyen.

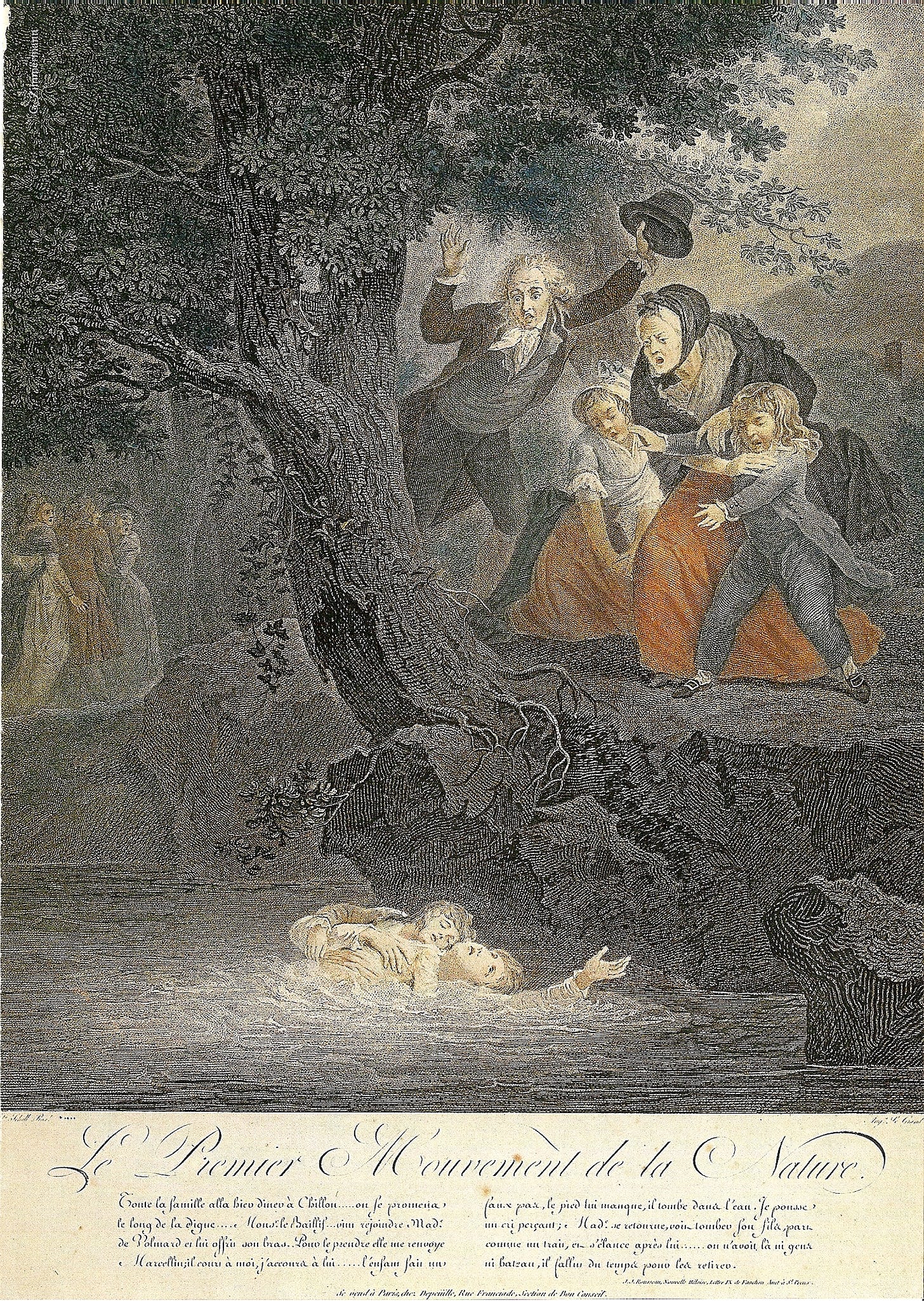

7. La Nouvelle Héloïse

Readers of War and Peace may remember that Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s bestselling epistolary novel is referenced by the old prince Nikolai Bolkonsky. He calls his daughter’s correspondent, Julie Karagina, “Héloïse”, an allusion to the book’s full title: Julie ou la nouvelle Héloïse.

It was the most successful work of fiction in the eighteenth century and made Rousseau the first literary celebrity, inundated with fan mail from his adoring readers. Napoleon was a fan, and here Camille implies that Robespierre considers it a “masterpiece”.

Also mentioned here is Rousseau’s Confessions, one of the first modern autobiographies. Camille finds Rousseau’s fiction too sentimental and his memoir… too confessional. Do I also detect a hint of jealousy from the young man so good with words about the most successful writer of their day?

8. Jean-Marie Hérault de Séchelles

A quote from Hérault’s The Theory of Ambition opened Part Two of A Place of Greater Safety:

We make great progress only at those times when we become melancholy – at those times when, discontented with the real world, we are forced to make for ourselves one more bareable.

As a member of the aristocracy and a lawyer, he was able to sit in the Parlement of Paris, which is currently the main embodiment of opposition to the king’s perceived despotism. Danton and Camille are just regular lawyers, with no political power or voice. Not yet anyway.

So they are “baffled” that Hérault has spent ten minutes bothering to talk to them. It’s almost as though Hérault knows that sometime soon, regular lawyers of the Third Estate are going to matter.

9. Café de Foy

Our protagonists have relocated to the Café de Foy in the Palais-Royal, the gardens and arcades surrounding the palace of the Dukes of Orléans. In 1781, the heavily indebted duke subdivided the Palais-Royal garden to create a shopping arcade. It would become a focal point of revolutionary activity.

When they arrived, a man was standing on a chair declaiming verses. He made some sweeping gestures with a paper, then clutched his chest in an agony of stage-sincerity.

The man is Fabre d’Églantine, whom we met in week 1, giving careers advice and public speaking tuition to a young Danton. Fabre is up on a chair with a sheet of paper. His performance foreshadows Camille, who will famously ascend a chair at the Café de Foy later in the story. He will not be holding a piece of paper.

The weight of the old world is stifling, and trying to shovel its weight off your life is tiring just to think about. The constant shuttling of opinions is tiring, and the shuffling of papers across desks, the chopping of logic and the trimming of attitudes. There must, somewhere, be a simpler, more violent world.

10. Duke of Orléans and Félicité de Genlis

Wolf Crawlers may recall that in Wolf Hall, Henry VIII’s ministers shave their heads to make the king’s baldness look like the latest fashion. The Duke of Orléans’ friends try the same stunt. “But no sycophancy can disguise the bald fact.”

Felicitie is a woman of sweet and iron wilfulnesss, and she writes books. There are few acres in the field of human knowledge that she has not ploughed with her harrowing pedantry.

War and Peace slow readers will hopefully remember Genlis as the cruel nickname the Rostovs reserve for Vera Rostova.

She is the mistress of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who has set himself up as a potential Alter Rex, an enlightened alternative to Louis XVI’s rule. He admired Britain’s constitutional monarchy and he plays a significant role in the early stages of the Revolution.

It is the first of many reminders that very few people expected these events to end in a republic. At times, the king is seen as an ally of the people against a conservative aristocracy. Camille Desmoulins’ views are, for no,w “eccentric” and “dangerous”:

‘I just like to see these people falling out amongst themselves, because the more they do that the quicker everything will collapse and the quicker we shall have the repbulic. If I take sides meanwhile, it’s only to help the conflict along.’

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Two, Chapter V. A New Profession (1788).

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Robespierre being so affected by passing the death sentence was a bit of a surprise, knowing what’s coming up. It's certainly a challenge to a common perception.

And, of course, we keep having to remember not to get too attached to any of these people - they may not be around for very long!

I'm certainly enjoying this,but I am finding it trickier than the Wolf Crawl - I think knowing more of the history would be helpful. At the moment, I'm not finding it easy to differentiate between the three major characters, but this may become easier as the cracks in relationships start to appear.

My favourite phrase? "(T)he chaste and peaceful sleep of emotional despots." It feels like the perfect take-down of a certain sort of manipulation.

I agree with Camille that Rousseau's Confessions is too confessional - I think Mantel is referring to the fact that in it Rousseau admits very explicitly to enjoying being spanked and also to dumping the children that he and his mistress had in orphanages and abandoning them, despite writing multiple books about how important it is to raise and educate children correctly. Pretty scandalous even for a memoir today!

I always think it's strange that people think Robespierre is cold when any account of him seems to be the opposite, like Mantel portrays him, rather as sensitive and sentimental and a bit of an overthinker.

I also think it's strange that a lot of people love Marie Antonette for... no reason that I can tell? when there were SO many cool women during the French Revolution, who were politicians, writers, journalists etc. Isn't that much more interesting and cooler?!