APOGS #2: The death of us

Part One, Chapter III. At Maître Vinot’s, Part Two, Chapter I. The Theory of Ambition and Chapter II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon.

Camille’s odd little face floated into her mind. If he’s not the death of us, she thought, I’ll smash my crystal ball and take up knitting.

Last Week | Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part One, Chapter III. At Maître Vinot’s, Part Two, Chapter I. The Theory of Ambition and Chapter II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon.

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can all be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

Danton arrives in Paris after a “lively” journey with a chatty, good-looking girl called Françoise-Julie. Danton will later incur a debt to Françoise, who will demand a large settlement for their illegitimate son. Danton becomes a pupil of the lawyer Maître Vinot, and Maître Perrin takes on Camille Desmoulins.

Danton meets his future wife, Gabrielle Charpentier, at the Café de l'École, owned by her father, a tax inspector, and frequented by lawyers. Danton tells M. Charpentier about his debt to Françoise-Julie Duhauttoir, due in the next four years. “I daresay something will happen between now and ‘91, to make your fortunes look up.”

Meanwhile, Danton and Desmoulins become friends. While Danton builds his career, Camille is the lawyer of lost causes, waiving his fee and visiting his condemned clients. “They always hang my clients.” Camille is a mess, and he knows it. Danton is worn down by his own servile careerism. Both men need “a holiday from the system.”

At the Café de l'École, Danton commiserates the civil servant Claude Duplessis on the death of his son-in-law. Danton knows the gossip: Camille Desmoulins is sleeping with M. Duplessis’s wife, Annette. Except he isn’t.

At the Duplessis house on Rue de Condé, the mother and two daughters are drowning in ennui – until Camille turns up. Lucile has a dark obsession with Mary Queen of Scots. When her mother, Annette, rejects Camille’s advances, the young lawyer proposes to Lucile. Danton thinks it deliciously depraved.

Claude Duplessis opposes the match, but Lucile threatens to tell her father about her mother's liaison with Camille.

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then this week corresponds to the following episodes:

In the 1780s, Louis XVI’s ministers at Versailles attempted to reform a crumbling system and reverse the crippling financial debt. The expense of the American Revolution compounded the situation. France’s impotence was being exposed by her inability to defend the pro-French “Patriots” in the Dutch Republic against the Orangists, backed by Britain and Prussia.

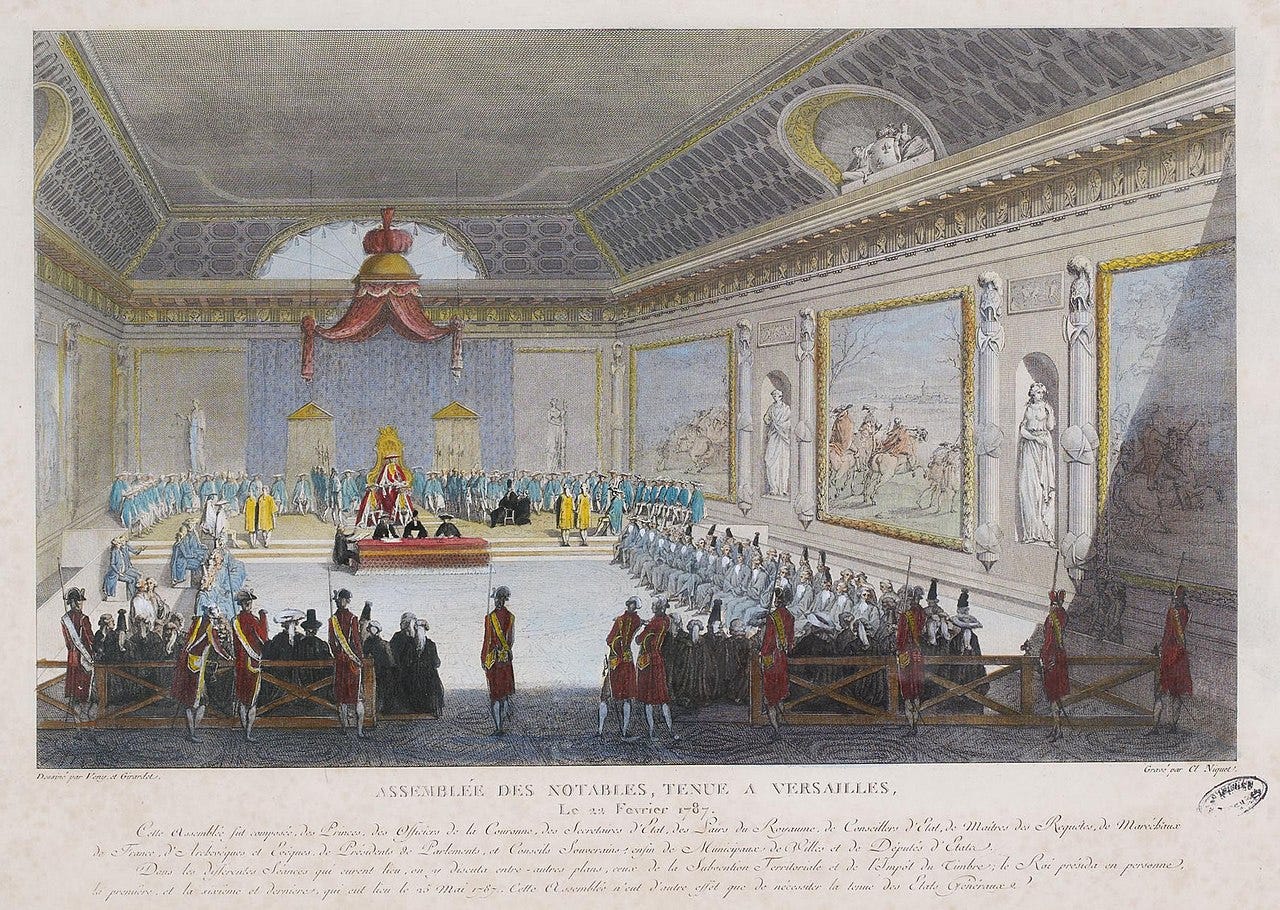

The king’s minister of finance, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, tried to raise confidence in the crown through increased spending. Calonne convinced the king to call an Assembly of Notables to agree on a package of tax reforms: a new universal land tax and the abolition of barriers to internal trade.

The assembly was composed of the traditional elite, and it met at Versailles in 1787. Louis and Calonne expected it to rubber-stamp the reforms. Instead, the elite assemblymen took their job seriously and scrutinised the proposals. The notables seized the opportunity to check the king’s power, while some began to call for an Estates-General, a meeting of all three estates, to resolve the national crisis.

Footnotes

1. Welcome to Paris!

‘What I like,’ she said, ‘is that it’s always changing. They’re always tearing something down and building something else.’

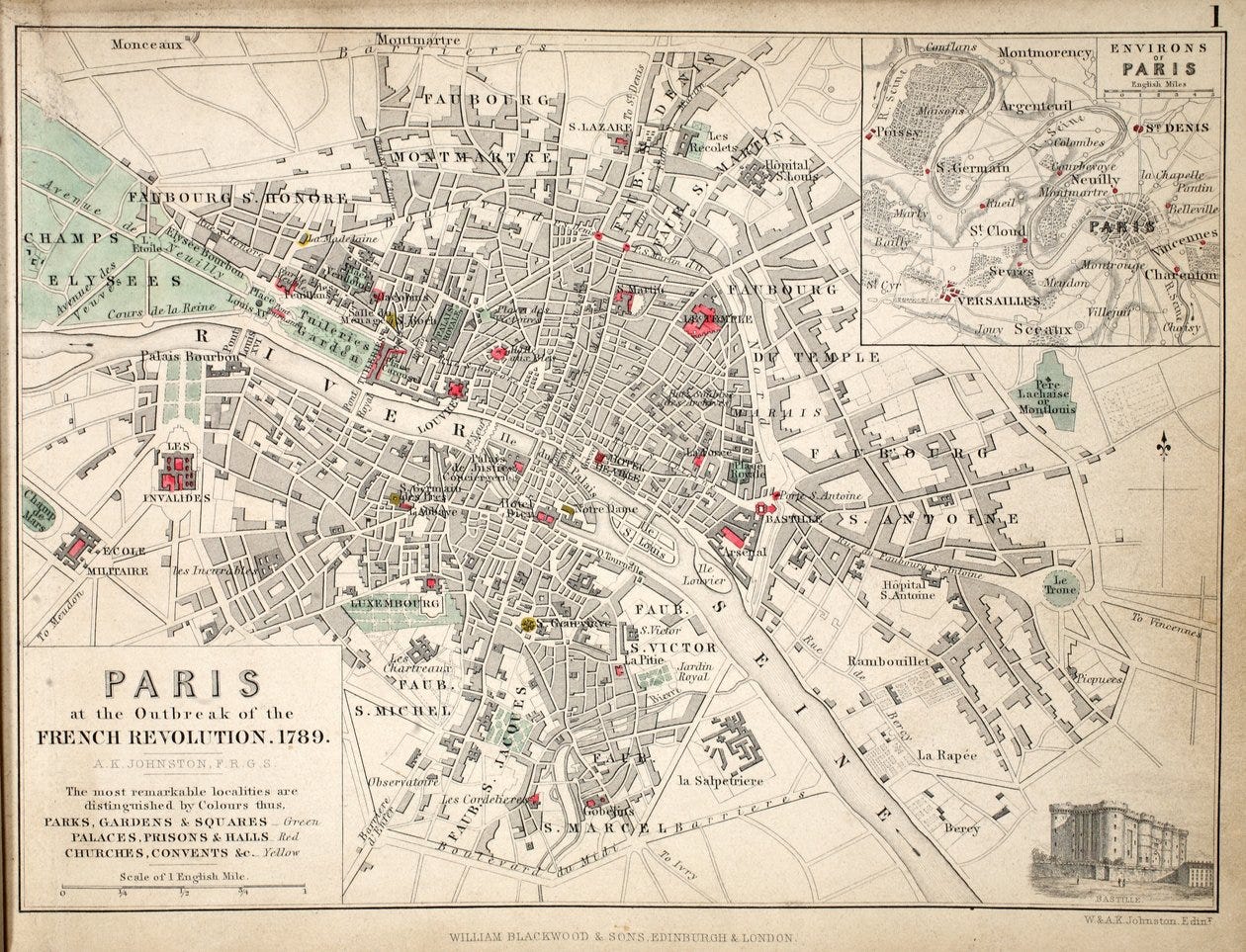

Danton arrives in Paris, our home for the next five months. Around 1700, the population of London surpassed Paris, but with 600,000 souls, it is still the second largest city in Europe. It is growing, mostly due to provincial Frenchmen like Danton and Desmoulins seeking work and opportunities.

Voltaire on Paris: “The centre of the city is dark, cramped, hideous, something from the time of the most shameful barbarism.”

The labyrinth of narrow, winding streets was ideal for insurrection and social unrest. After decades of revolt and revolution, Georges-Eugène Haussmann began tearing down the old city in the 1850s and replacing it with the grand boulevards and public buildings of modern-day Paris.

2. Merit and money

Elevation from here is not so much a matter of merit, as of money.

Did you notice that the two Parisian lawyers, Vinot and Perrin, are the same men mentioned on page 1 in the reveries of Camille’s father, Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins?

Nepotism gets Camille’s foot in the door. He’s “an old friend’s boy.” Danton intends to make his way on merit. But the legal profession is not a meritocracy. Venal offices are bought and sold, and Danton is soon required to buy one from the new husband of his old mistress.

It is a torrid, inhospitable climate that “wears down” the impatient and ambitious Danton. When Camille talks of revolution, his new friend considers a job opportunity:

‘This revolution – will it be a living?’

We must hope so. It will also be a dying.

3. Jean-Paul Marat

On the Pont-Neuf the public letter-writers had their booths, and traders set out their goods on the ground and on ramshackle stalls. He sorted through some baskets of books, secondhand: a published romance, some Ariosto, a crisp and unread book published in Edinburgh, The Chains of Slavery by Jean-Paul Marat. He bought half a dozen for two sous each. Dogs ran in packs, scavenging around the market.

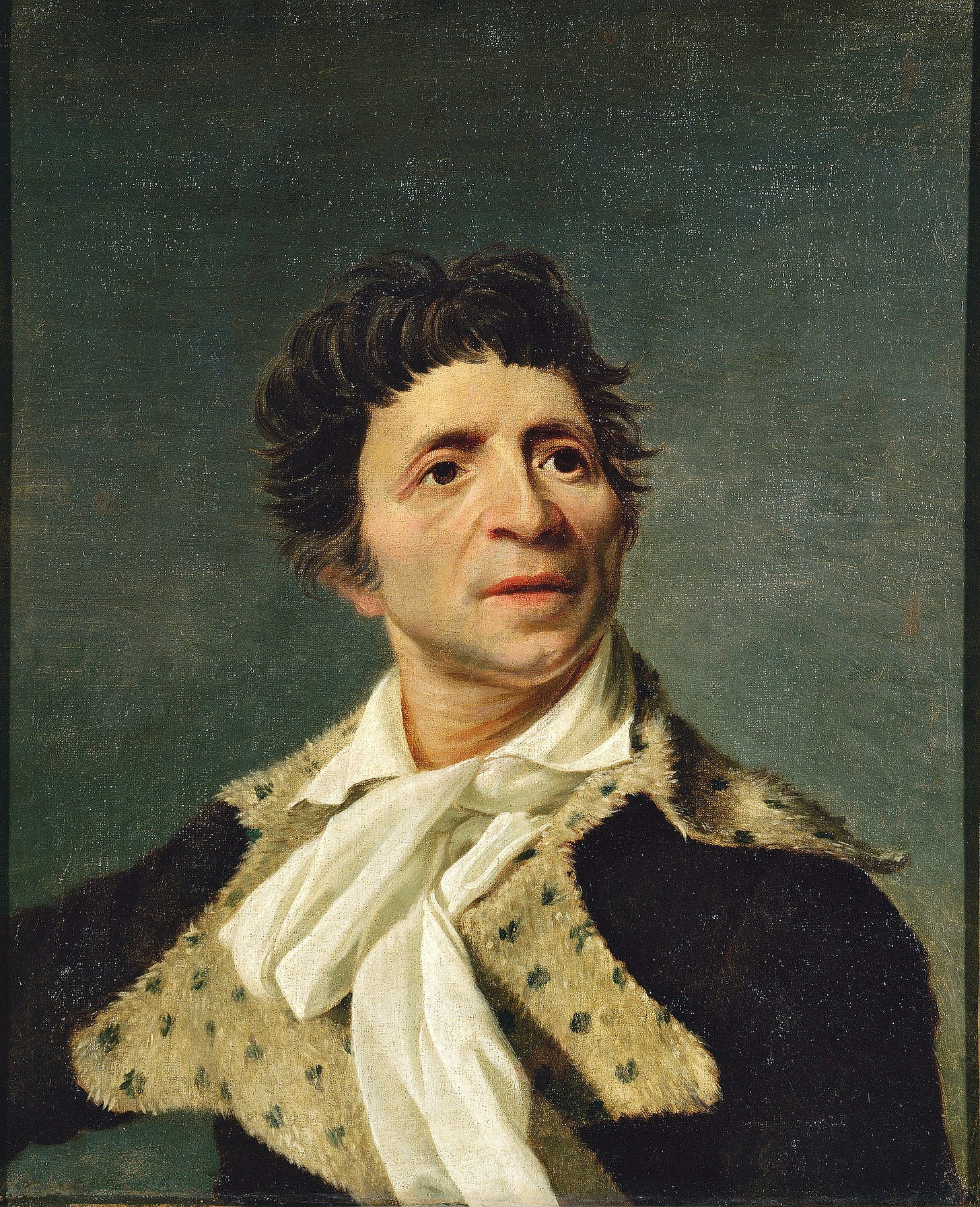

Danton picks up a copy of an early political work by Jean-Paul Marat. As a radical journalist and defender of the militant sans-culottes, Marat will play a major role in the Revolution. In her note at the beginning of the novel, Mantel says this about Marat:

There is one character who may puzzle the reader, because he has a tangential, peculiar role in this book. Everyone knows this about Jean-Paul Marat: he was stabbed to death in his bath by a pretty girl. His death we can be sure of, but almost everything in his life is open to interpretation. Dr Marat was twenty years older than my main characters, and had a long and interesting pre-revolutionary career. I did not feel that I could deal with it without unbalancing the book, so I have made him the guest star, his appearances few but piquant. I hope to write about Dr Marat at some future date. Any such novel would subvert the view of history which I offer here. In the course of writing this book I have had many arguments with myself, about what history really is. But you must state a case, I think before you can plead against it.

Unfortunately, we never got Mantel’s Marat. It would have been fascinating to read her alternative view of the Revolution.

The grammar in the above quote is ambiguous: is the “crisp and unread book” from Edinburgh also The Chains of Slavery? Perhaps not. But I was curious to read that The Chains of Slavery was written and published in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, my hometown.

Marat was born in a Prussian region in modern-day Switzerland in 1743. He lived in France and then England, practising as a doctor and hanging out with artists and intellectuals. Chains of Slavery is an attack on England’s constitution and the king’s influence over Parliament. Danton would be a sympathetic reader:

‘A parliament’s what we need, don’t you think? I mean a properly representative one, not ruined by corruption like theirs. Oh, and a separation of the legistlative and executive arms. They fall down there.’

At the time, France had 13 parlements. Unlike the English Parliament, these were not democratic legislative assemblies. They were courts of last appeal and the body that approved the Crown’s laws and edicts in their jurisdiction. The parlements were composed entirely of aristocrats who had bought or inherited their office.

More: A short biography of Jean-Paul Murat (contains spoilers!)

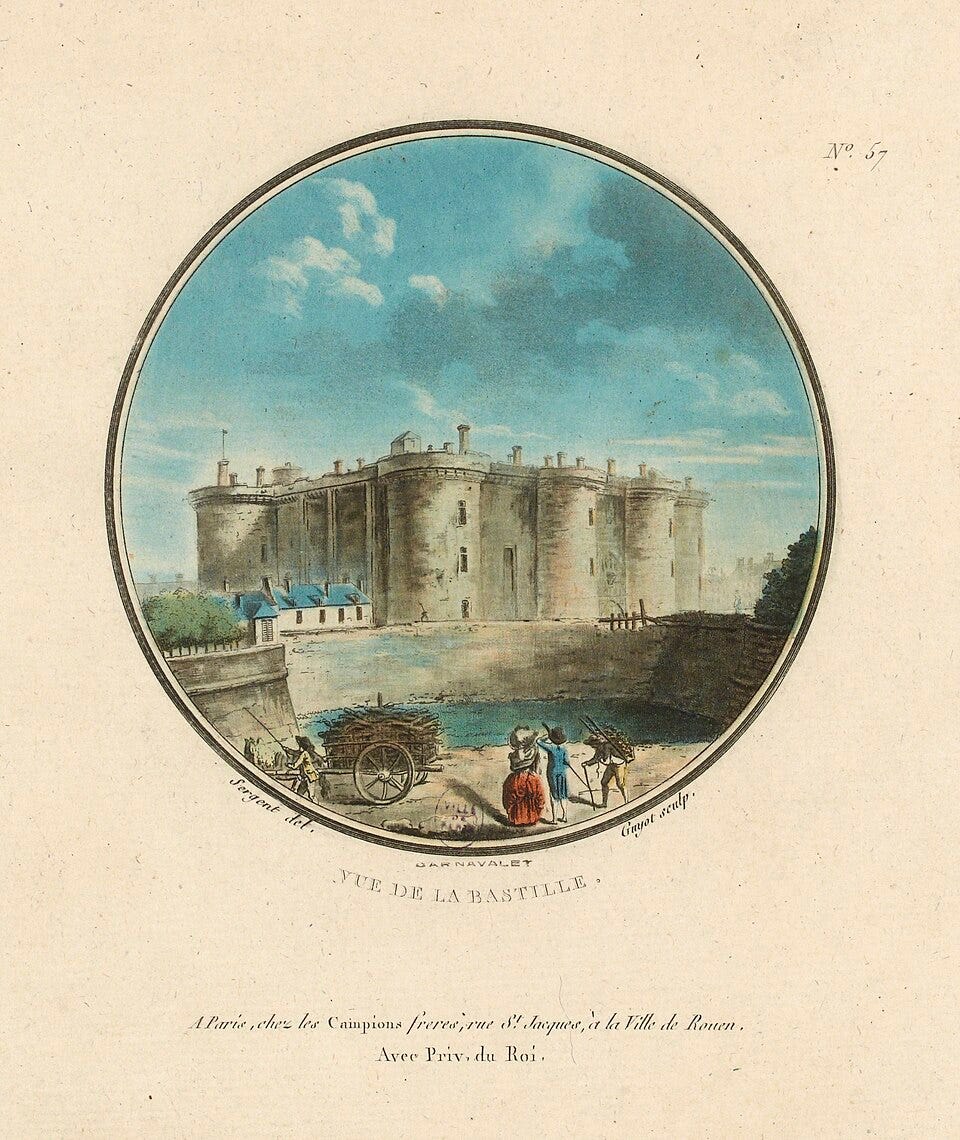

4. The Bastille

‘I expected it to be bigger.’

Of course, Danton is underwhelmed by France’s most famous fortress and prison. By 1780, its reputation is far greater than its reality. Ex-prisoners wrote about their terrible experiences within. Constantin de Renneville wrote about being chained up in its dungeons beside a forgotten corpse, the Abbé Jean de Bucquoy called it the "hell of the living”.

These accounts often exaggerated the horrors of the Bastille, creating a “Black Legend” that took hold of the popular imagination. As Danton notes, it is the stories that matter:

What really matters isn’t the height of the towers, it’s the pictures in your head: the victims gone mad with solitude, the flagstones slippery with blood, the children birthed on straw.

It is the idea of the Bastille: a symbol of a cruel and despotic regime. Already, in the 1780s, there are calls for its abolition and destruction. After spending time in the Bastille, Simon-Nicholas Henri Linguet wrote his Mémoires sur la Bastille, encouraging the king to destroy the prison. A conservative and defender of Louis XVI, Linguet will be guillotined in 1794.

5. A theory of ambition

‘Call yourself d’Anton,’ he advised. ‘It makes a better impression … It shows the right kind of urges. Have comprehensible ambitions., dear boy.’

D’Anton has the spurious air of nobility about it, at a time when ambition means buying or marrying your way into the aristocracy. “Build slowly,” Vinot says, and have a “Life Plan.”

Maximilien de Robespierre will drop his “de” to make his name sound less aristocratic. And it won’t be long before it will be necessary for us to disguise any noble blood in our veins, out of fear of having it spilt.

“I do have some ambitions of my own,” Camille tells Danton. Danton wants “to get to the top”. Camille wants to feel warm, eat “on a grand scale,” and “wake up every morning beside someone you like.”

I love these messy and confused portraits of Danton and Camille. Yes, they have radical and revolutionary ideas. But also complicated private lives, simple urges, familiar frustrations. Comprehensible ambitions.

6. Two Antoines

There wasn’t enough evidence to bring it to court. But then Antoine, he’s a lawyer too, so there wouldn’t be. I expect he’s good at fixing evidence.

Camille tells Danton about two of his relatives, both confusingly called Antoine.

Without getting into spoilers, both Antoine Fouquier-Tinville and Antoine Saint-Just will play a significant role in the fates of both Camille and Danton. So this section is all foreshadowing and foreboding. If you know, you know.

‘He’s one of these boys, sort of big and solid and conceited, incredibly full of himself, he’s probably steaming about at this very minute working out how to get revenge. He’s only nineteen, so perhaps he’ll have a career of crime, and that will take the attention off me.’

7. The Marquis de Lafayette

‘What is it that the Marquis de Lafayette has said?’

’He has said that the Estates-General should be called.’

We cannot let pass the first mention of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, without a quick flit across the water:

“America's favourite fighting Frenchman” fought in the War of Independence. Across the United States, there are towns, streets, squares, parks and even a mountain named after him.

He returned to France a hero and was appointed to the Assembly of Notables, where he was a liberal and radical voice, calling for a national assembly that represented all of France. The Estates-General was last called in 1614. As Perrin notes, the commoners of the Third Estate will always be outvoted 2-1 by the nobility and the clergy.

Danton resents Lafayette’s reputation and will later oppose him politically. But for now, he must defend the decorated war hero:

Yes, d’Anton thought, and while I was poring over the tomes in Vinot’s office, he was leading armies. Now I am a poor attorney, and he is the hero of France and America. Lafayette can aspire to be a leader of the nation, and I can aspire to scratch a living.

Danton wants to get to the top. And in Lafayette, he perceives ambition and, perhaps, an obstacle.

8. Mary Queen of Scots

Lucile Duplessis’ journals are lost, except her diaries of the summers of 1788 and 1789 and from June 1792 to February 1793.1 They reveal an intelligent and astute observer of life and revolution. Here is her in 1788:

What a sad fate it is to be a woman. How much she has to suffer – slavery, tyranny, that is her share. Yet they [masc.] want us to adore them. I believe that they would suffer us to erect altars to them and prostrate ourselves before them with censer in hand, asking them for forgiveness for the evils they make us suffer. To hear them speak, we are celestial beings, nothing is equal to us. Ah! may they deify us less and leave us free!

Mantel gives Lucile a morbid and melancholy obsession with Mary Queen of Scots, the Scottish cousin of Elizabeth I, executed at Fotheringay Castle on 8 February 1587. It could be said that Hilary Mantel had something of an obsession with the beheaded: all four of her major historical novels end with decapitation.

‘Three hundred people had assembled to watch her die. She entered through a small side door, surprising them; her face was composed. The scaffold was draped in black. There was a black cushion for her to kneel upon. But when her attendants stepped forward they slipped the black robe from her shoulders, it was seen that she was clothed entirely in scarlet. She had dressed in the colour of blood.’

This is a violent book. But the three main male characters so far seem relatively harmless compared to the dark interior world of Lucile Duplessis. Curiously, the first image of execution comes from the novel’s first extended reverie from a woman’s point of view. Death arrives first as the bored fancy of a young woman considering a marriage proposal:

… these death-wishes, these images, sweet Jesus, ropes, blades and her mother’s lover with his half-dead-already air and his sensual bruised-looking mouth.

Tangent: Mary Stuart’s last night is hauntingly evoked in Sandy Denny’s song Fotheringay:

How often she has gazed from castle windows o'er, And watched the daylight passing within her captive wall, With no-one to heed her call. The evening hour is fading within the dwindling sun, And in a lonely moment those embers will be gone And the last of all the young birds flown. Her days of precious freedom, forfeited long before, To live such fruitless years behind a guarded door, But those days will last no more. Tomorrow at this hour she will be far away, Much farther than these islands, Or the lonely Fotheringay

9. Dangerous books

Then she folded it and tucked it inside a volume of light pastoral verse. Immediately, she thought that she might have slighted it; she took it out again and placed it inside Montesquieu’s Persian Letters. So strange was it, that it might have come from Persia.

Camille’s love letter is first hidden inside a poetry book. But it tells us a lot about Lucile that she thinks this is inappropriate and relocates Camille within the pages of Montesquieu. Persian Letters (1721) is an epistolary novel about two fictitious Persian noblemen travelling in Europe. There is something exotic, mysterious and a little menacing about this young lawyer Camille Desmoulins.

Her mother, Annette, says, ‘Perhaps you would like to file it inside my copy of Les Liaisons Dangereuses.’ A very different epistolary novel written in 1782 by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. This tale of aristocratic corruption and depravity was a literary sensation, a bestseller that reached the Palace of Versailles, where Marie Antoinette owned an illicit copy with a blank cover.

At the end of the chapter, Lucile resolves to hide future letters in Gabriel Bonnot de Mably’s Doubts on the Natural Order of Societies. A dry philosophical text seems a much safer bet. But then again, like his friend Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Mably opined about liberty and the collective will. These ideas are set to change all our lives, including Lucile, and make our days considerably less boring and more dangerous.

Les Liaisons Dangereuses: A Book That Keeps Burning (The London Magazine)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Two, Chapter III. Maximilien: Life and Times and Chapter IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood.

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

I cannot find an English translation, and the French version is out of print. Let me know if you track down a copy.

I love this book. It was the first Mantel book I read, when I ordered it from the library as a teenager, and I still haven't got over it. I've read it a few times and still every time I read it it hits me again. It's hard to pinpoint why, but I love the sort of perspective it's written from, sort of zooming in and out. I love the way Mantel writes, it's as simple as it could be to paint the images she wants, and still it's very elegant. I love the slightly detatched, humourous tone of most of it, almost but not quiite hiding the depth: like Lucile, young and bored and her obsession with Mary Tudor and dying young is sort of funny... but at the same time it's incredibly emotionally affecting, you can't help but grieve for her and her early death, not of ennui at all.

In fact, they all seem like such normal people and I think that's part of the appeal of the French Revolution: that it was normal people who made such huge changes, who created something amazing and terrible, and died for it. Well, Camille doesn't seem normal but he is weird in a recognisable way too!

I enjoyed the Saint Just reference, I wish the book had more Saint Just and more Couthon. Or I suppose that would be a different story with a different focus, but I'd like to read Mantel's version of that anyway.

I always wonder why there isn't much of Danton as an older child at school - if I remember correctly there are some amazing stories about him out there

I remember being so interested in Anne Boleyn's life and death when I was in my teens and early twenties because of the drama of it all, so I can sympathize with Lucile. When you've had an apparently ordinary upbringing, the thought of all the historical drama captures the imagination. I'm sure Lucile never thought she would end up living (and dying) in such times as the ones she ended up in.

I'm so glad when she was reworking APoGS for publication, Mantel added in so much about the lives of the women. It's fascinating to see things through their perspective. I'll forever be sad that we didn't get Mantel's Marat novel, or her final book that was in conversation with Jane Austen.