APOGS #1: History is fiction

Part One. I. Life as a Battlefield & II. Corpse-Candle

Camille Desmoulins, 1793: ‘They think that gaining freedom is like growing up: you have to suffer.’

Maximilien Robespierre, 1793: ‘History is fiction.’

Main Page | Reading Schedule | Cast of Characters | Further Resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part One. I. Life as a Battlefield & II. Corpse-Candle. Once you have read these two chapters, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can all be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

We begin with three boys bursting forth into the world.

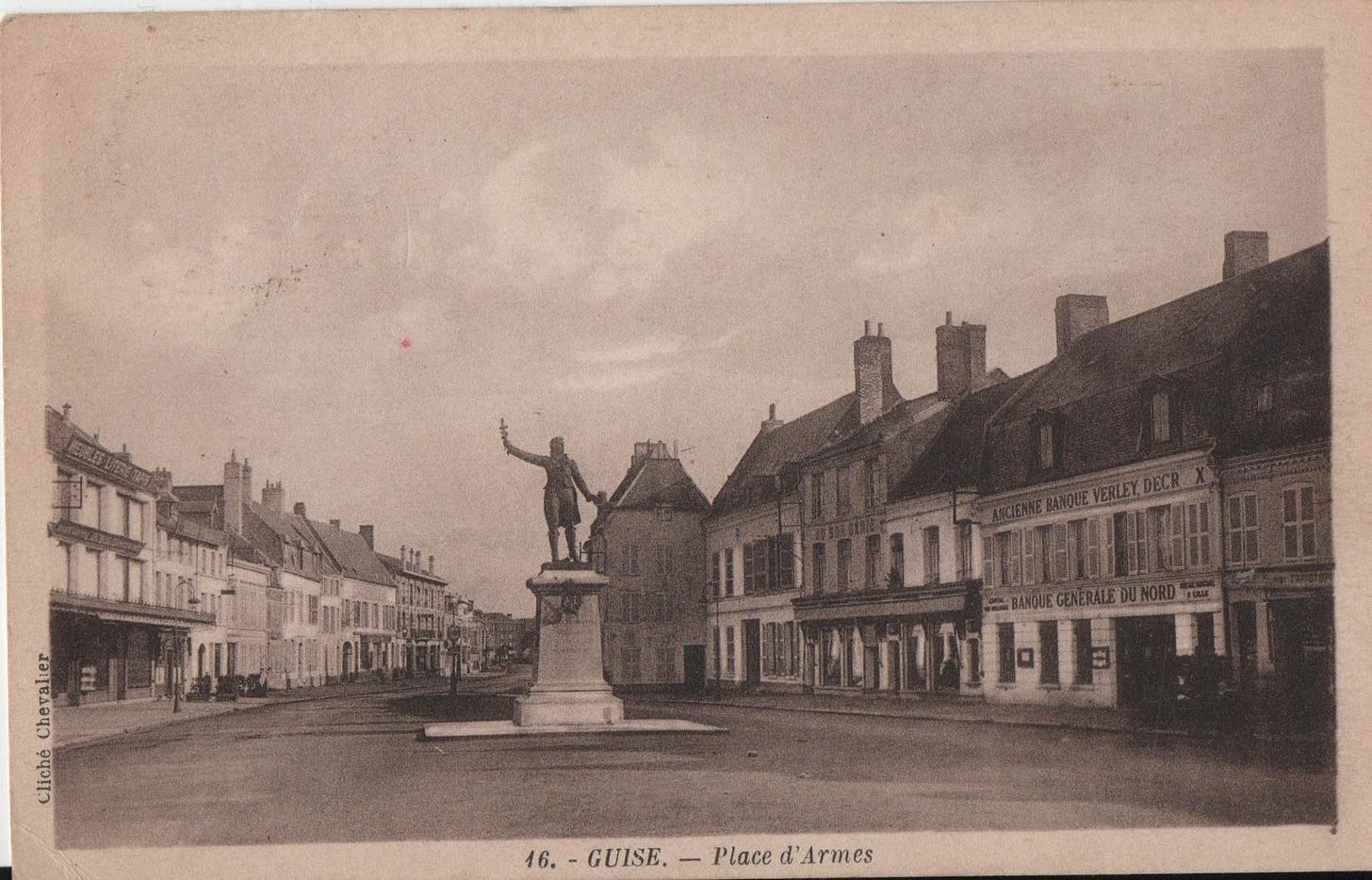

In Guise, Camille Desmoulins is the eldest son of the lawyer Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins and his wife, Madeleine. Everything astonishes Camille. In Arcis, Georges-Jacques Danton is savaged by a bull and trampled by pigs, his face disfigured for life. “That’s positively the last time I’ll be trampled on by any animal,” he tells the world. “Four-legged or two-legged.”

In Arras, Maximilien Robespierre is born, the love child of François de Robespierre and Jacqueline Carraut. His mother dies giving birth to her fifth child, and Maxmilien is taken in by her father, a brewer.

But we must get on with life. Camille Desmoulins is sent to school and comes back disturbingly intelligent with a disconcerting stutter. His mother’s relatives foot the bill for his education at Louis-le-Grand in Paris, where he meets a scholarship student called Maximilien Robespierre. In 1775, Robespierre is chosen to address the King and Queen during a visit to the school. It is raining, and they do not stay to hear him finish.

Georges-Jacques Danton would also like to be in Paris. He wants to be somebody, but he doesn’t realise this until one day he meets an unemployed polymath called Fabre d’Églantine, who draws his dislikeness and teaches him how to speak, and go on speaking, for hours, days at a time. “Study law”, he advises Danton. “Law is a weapon.”

We are now in the 1770s. Bread prices and national debt are rising. The rich love their lawyers, and Camille’s father is in demand. One day, when Camille is back home with his father, he tells the district’s premier nobleman what he thinks: “In fifteen years you tryants and parasites will be gone.”

Danton visits his sister, Marie-Cécile, in a nunnery. She will pray for his soul, all day every day, so he doesn’t have to. He will not depend on God. He is going to Paris to be somebody, and make his fortune.

Background

For a breezy, accessible overview of the events of the French Revolution, I recommend Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast. Each week, I’ll link to the relevant episodes that correspond to the narrative in A Place of Greater Safety:

France was the most populous country in Europe on the eve of the revolution, with around 28 million people. Society was divided into “three estates”: the church, the nobility, and the rest. This “third estate” comprised 98% of the population, from the poorest peasants to the emerging middle class (the bourgeoisie).

This would later be known as the Ancien Régime: the old social and political system before the revolution.

Revolution was not inevitable, but change was desperately needed. The French monarchy was on the verge of bankruptcy; the tax burden fell disproportionately on the poorest, with collection farmed out to unscrupulous and deeply resented agents.

Public offices were bought and sold; the legal system served privilege rather than justice; customs duties hindered internal trade; and agricultural land was divided into small, inefficient plots of land.

At the same time, thinkers of the French Enlightenment corresponded in a “Republic of Letters” across Europe and America, challenging received opinions in science, philosophy and politics. Figures like Voltaire and Montesquieu envisioned a society organised by reason rather than tradition.

In 1774, Louis XVI inherited this broken regime, hopeful that it could be reformed by the “enlightened absolutism” of a strong monarchical government. But the challenge was too great, with entrenched resistance to reform and the growing demand from the Third Estate for a say in how the country would be governed.

Footnotes

1. Camille Desmoulins

Everything astonishes him: his father’s diatribes, the speckles on an eggshell, women’s hats, ducks on the pond.

Christened Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins, this boy will die aged 34, one year older than his father is now. His father is disillusioned by the world. He thinks that when his son is “forty”, Camille will be “greying, and worried sick about” his eldest son. Camille will not live long enough to lose that look of surprise.

It is Guise, Picardy; he is thirty-three years old, husband, father, advocate, town councillor, official of the bailiwick, a man with a large bill for a new roof.

Is the roof a reference to fixing it while the sun is shining? In this chapter, we are encouraged to follow Jean-Jacques Rousseau in seeing the family as a microcosm for society:

The head of the state bears the image of the father, the people the image of his children.

The quotation is from The Social Contract (1762), one of the books that influenced the French Revolution. Camille’s father is sympathetic to Rousseau’s ideas of political equality and liberty. But he is also a lieutenant-general of the bailiwick, administering the king’s government in Guise. He is also employed by the Prince de Condé1, a prince of the blood and the district’s premier nobleman.

His son has no conflicting interests:

‘You are making a nation of Cromwells. But we can go beyond Cromwell, I hope.’

For those reading Wolf Crawl, this is Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, after the English cut off their own king’s head. It is not his ancestor, Thomas Cromwell. Until Mantel wrote Wolf Hall, Oliver was the more famous of the two men.

The dead don’t come back, to quibble or correct.

More: Introduction to Rousseau and the Social Contract (Then & Now)

2. Georges-Jacques Danton

Did you notice how our three protagonists are associated with animals?

From his window, Camille watches a dog catch a rat. ‘Oh, poor rat.’ Later, he compares himself to Romulus, the founder of Ancient Rome, left on a hillside and suckling a she-wolf.

There is a story that Georges-Jacques Danton suckled a cow, inciting the jealousy of the bull that tore up his face. Was there something in the milk? For Danton grew up to be as big as an ox with the bellow of a bull.

If you are going to be ugly it is as well to be whole-hearted about it, put some effort in.

Notice our fathers. They are men with great dreams and greater disappointments.

Danton’s stepfather is Jean Recordain, He is “inventing a machine for spinning cotton. He said it would change the world.” It sounds a lot like the Spinning Jenny, invented in secret by James Hargreaves in the 1760s. The Spinning Jenny will change the world. M. Recordian will not.

His stepson, in contrast, is impatient to “get on” in this world and rise to the top.

Tangent: James Hargreaves and the Invention of the Spinning Jenny (ThoughtCo)

3. Maximilien Robespierre

‘He’s a chilly little article.’

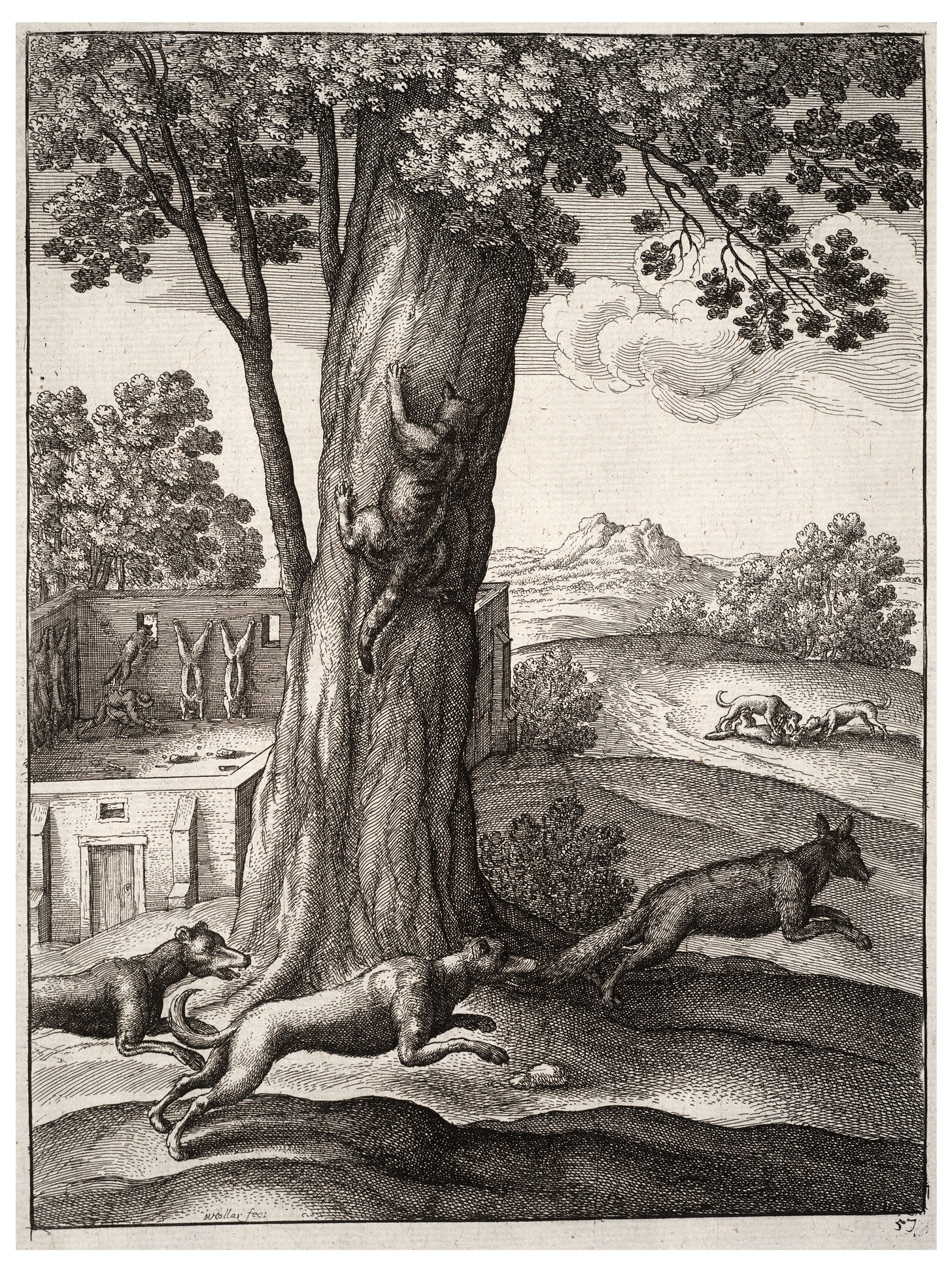

Camille is the rat. Danton is the bull. Maximilien Robespierre is the cat. When his aunt read him one of Aesop's fables, ‘The Fox and the Cat’, he “slid down on to the floor, and played with the bit of lace at her cuff.”

In the story, the wily fox has many tricks, but the cat has one. The fox is caught and killed; the cat climbs a tree. Maximilien has one trick, and from his tree the world is clear. When he addresses the king, it doesn’t matter that the king isn’t there:

Without a smile, he bid a fond and loyal goodbye to the monarchs who were no longer in sight, and hoped that the school would have the honour, at some future time…

Well, a cat may look at a king.

In the room above him, his mother is dying. He, Maximilien, sees the pages of his aunt’s book fan over. He is the tortoise who wins the race, the wise crow that fills the pitcher with pebbles so he can drink. The honey bear that upsets the beehive and is stung and stung, again and again.

What do we think of freedom? Was it easier for our ancestors to bear their lot, for they did not know they were not free? Ask Maximilien’s dove, given to his sisters in a a pretty gilt cage. “We put the cage outside so he would feel free,” said Charlotte. Maximilien said:

‘He was not a free bird. He was a bird that needed looking after. I told you. I was right.’

Later, ideas from the American Revolution will vault the walls of the Louis-le-Grand and infect the minds of Maximilien and Camille. ‘You think it is better if people’s hopes are not raised?’ Maximilien asks the liberal-minded Father Poignard.

The French are caged doves, lashed by the rain, “the thunder rolling overhead.”

4. Louis-le-Grand

Maximilien and Camille will be friends of a kind; co-revolutionaries. One will kill the other. So when they first meet, Maximilien recalls the dead dove in the gilt cage:

He put his glasses back on. The child’s large dark eyes swam into his. For a moment he thought of the dove, trapped in its cage. He had the feel of the feathers on his hands, soft and dead: the little bones without pulse. He brushed his hand down his coat.

Later, he tells Father Poignard that he is Camille’s “keeper”. It is an allusion to Cain’s words to God after he has murdered his brother Abel: “Am I my brother's keeper?” Cain is the first murderer, and Maximilien and Camille are brothers-in-revolution.

At Louis-le-Grand, they meet another future revolutionary, Stanislas Fréron, and Louis Suleau, who correctly predicts that they will be on opposite sides of the coming conflagration:

There will be a war in our lifetime, he told Camille, and you and I will be on different sides. So let us be fond of each other, while we may.

5. Corpse-candle

What Camille finds outside the walls excites and appals him. It is a benighted city, he said, forgotten by God; a place of insidious spiritual depravity, with an Old Testament future. The society to which Freron Fréron to introduce him is some huge poisionous organism limping to its death; people like you, he said to Maximilien, are the only fit people to run a country.

We are now in the year 1774. Do not deceive yourself. You may think you are reading a book, in broad daylight, and you are safe from what is coming. You are wrong.

It is not a midday luminary, but a corpse-candle to the intellect; at best, it is a secondhand lunar light, error-breeding, sand-blind and parched.

A corpse-candle is an omen of death; small bright lights that portends your end. You have seen it. Now you have little choice but to follow.

6. The Last King of France

Louis XV died at Versailles on 10 May 1774, “in the huge antechamber known as the Œil de Bœuf.” The name refers to this circular “bull’s eye window”:

Optimism surrounds the coronation of the new king, Louis XVI and his Austrian princess, Marie-Antoinette. There is the suggestion that Louis is the resurrecteed Henri IV (1589 – 1610), known as “Good King Henry” or “Henry the Great”.

Henri IV was the first king of the House of Bourbon and reconciled the Catholic and Protestant factions after the French Wars of Religion. Raised a Protestant Huguenot, he pragmatically converted to Catholicism in 1593, declaring that “Paris is well worth a Mass.” He was killed by a Catholic assassin in 1610.

Our current king does not have the same appetite for government. When one of his ministers resigns, he says, “You’re lucky … I wish I could resign.”

7. The price of bread

‘Under Robespierre, blood flowed, but the people had bread. Perhaps in order to have bread, it is necessary to spill a little blood.’

In April and May 1775, bread riots swept France. This was known as the Flour War, and was the first outbreak of unrest that led to the Revolution. As Mantel explains, the price of bread, grain hoarding (real and imagined) and speculation were central issues in the events to follow.

More: The Flour War (World History)

8. Fabre d’Eglantine

Everthing he said was both serious and not serious.

There’s something attractive about Fabre d’Eglantine. He breezes into the book. He’s a frank failure and he might just be our friend. History will mostly remember him for giving new names to the months after the Revolution: Germinal, Floréal, Prairial… But Hilary Mantel has him give Danton career advice and tuition in public speaking:

‘You could play the villains. You’d be well recieved. You’ve got a good voice there, potentially.’

D’Eglantine and Danton’s futures are now entwined, whether they want it or not.

9. Beyond Cromwell

The episode involving the Prince de Condé is referenced in biographies of Camille Desmoulins. Camille’s mention of going “beyond” Oliver Cromwell foreshadows his radical republicanism during the revolution, where he accused moderates of aping the military despotism of the English revolutionaries:

“The true Jacobins are of this party, because they want not the name of the Repubhc, but the thing; because they do not forget that in the Revolution of 1649 England, under the name of a Republic, was governed monarchically, or rather as a mihtary despotism by Cromwell … This word Republic which Cromwell had everlastingly in his mouth does not deceive me.”

The first two chapters have referenced the English and American revolutions. English republicanism led to a constitutional monarchy and military rule under Cromwell. Radicals like Camille look to England as a warning of a revolution betrayed. From America, come ideas and young men who have been fighting for freedom and democracy.

10. The Austrian

‘I am terrified of being bored,’ she says.

Marie Antoinette was the daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I, and her marriage secured an unpopular dynastic alliance with Austria after the Seven Years' War. She was 14 when she left her home behind and arrived at the Palace of Versailles.

Her lavish lifestyle and foreignness made her a target for criticism of the Regime before and during the revolution.

Hilary Mantel has written about Marie Antoinette in various essays.2 In 2013, she wrote a piece titled “Royal Bodies” that discusses the precarious position of female consorts in the public eye, comparing the fates of Marie Antoinette, Anne Boleyn, Princess Diana and Kate Middleton, now Catherine, Princess of Wales.

Marie-Antoinette was a woman eaten alive by her frocks. She was transfixed by appearances, stigmatised by her fashion choices. Politics were made personal in her.

The essay provoked predictable outrage in the British press, cynically incapable of getting past the opening description of Kate Middleton as “a disjointed doll on which certain rags are hung.” The full article is well worth reading, as is everything Mantel wrote on how misogyny operates in the body politic.

More: Royal Bodies by Hilary Mantel (paywall)

Tangent: Who owns the royal body? Public interest in royal health reveals anxieties about our rulers (The Conversation)

11. The death of Voltaire

In May, he died. Paris refused him a Christian burial, and it was feared that his enemies might desecrete his remains. So the corpse was taken from the city by night, propped upright in a coach: under a full moon, and looking alive.

This ghoulish image has a spectral hold on the story to come. Voltaire was an outspoken critic of the church and a defender of freedom of speech and freedom of religion. Like Rousseau, he is one of the undead sentinels of the revolution. His posthumous flight from Paris foreshadows Louis XVI’s failed attempt to escape the city by night. Voltaire was dead. Louis soon would be.

More: How Voltaire Went from Bastille Prisoner to Famous Playwright (Smithsonian Magazine)

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part One, Chapter III. At Maître Vinot’s, Part Two, Chapter I. The Theory of Ambition and Chapter II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Readers of War and Peace may be interested to know that the prince’s grandson was Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien. His execution in 1804 caused international outrage and contributed to the outbreak of war in 1805 between France and Russia.

Fatal Non-Readers, London Review of Books (paywall); The Perils of Antoinette, The New York Review (paywall); Unsolved Mystery of the Dauphin’s Private Parts, Literary Review.

This feels incredibly timely. Men with troubled childhoods, sent away to school, feeling that they know how the world should be run (SPOILER ALERT: they will make a mess of it), becoming disruptor and causing chaos? Along the way, they attract the support of the poor, even though they will continue to suffer?

Thank God it couldn't happen here...

A couple of people have told me that they gave up on the book. I think, having started on the Wolf Crawl, that I've picked up on Mantel's style - so I can work out whose perspective we're viewing something from.

Like Wolf Crawl (I assume), we're going to be following great men to their early deaths. Again, we're going to be interest not so much in the 'what?' as the 'why?' of events.

I notice Mantel throws in a life expectancy statistic. I assume - but may be wrong - that if you survived the first few years of life you had a pretty good chance of living to a ripe old age (if you were a man, that is: maternal mortality, as we see, presenting a severe risk).

We're already seeing the impact of wheat prices, soon to be a factor in the uprising. Some years ago, I went round the customs museum - Musée national des douanes, and well worth a visit (seriously!) - which had a display about how salt was also an important factor.

It looks like we're in for a fascinating few months.

And thanks to Simon for posting on a bank holiday. I'm not sure that the revolutionaries would approve, but I certainly appreciate it.

I have been off Substack for a while as it was feeling overwhelming in conjunction with general life. I had to end my other two subscriptions and I have been focusing on what grounds me away from the majority of things social media related. I realised even trying to re-read War and Peace and Wolf Hall was too much at this moment. However, I have had 'A Place of Greater Safety' slow read at the back of my mind and when I saw Simon posted yesterday on Instagram about it starting today a wee voice in my head encouraged me to read it again. So here I am, back on Substack only for this one account and raring to begin APOGS with a lot of lovely people.