📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 44 of Wolf Crawl

This week we are reading the first half of ‘Corpus Christi, June–December 1538’. This runs from page 563 to 598 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “Wyatt has followed the Emperor from the shores of Spain to Nice…” It ends: “It’s not worth it. Nobody’s worth it.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

Early June. Thomas Wyatt is back from his embassy at the imperial court, complaining about Spain, his king’s lack of trust, and Cromwell’s little man, Edmund Bonner. He’s seen Pole close enough to kill him. He, Cromwell, opens a gift of beavers from Danzig and bids Wyatt stay for supper.

Spain and France have signed a Ten-Year Truce. Henry is furious with everyone. He feels deceived and betrayed. He threatens to invade France and marry into the House of Cleves. Cromwell puts Hans on the road to paint more prospective brides for the King of England.

Late summer at Lewes with Gregory and his grandson. The sky: like a mirror, light without shadow. August: Geoffrey Pole is arrested. He, Cromwell, ‘is preparing to bring down two of the richest and most noble families in England.’

In July, the king watches the new Bale play about Becket.1 In September he rides down to Canterbury to open the former saint’s tomb. His dogs prowl and Becket’s two skulls are seized. He keeps them under lock and key in case his king changes his mind and makes the knave a saint again.

Bonner replaces Gardiner in France, and the Bishop of Winchester returns like a bad dream. He, Cromwell, writes to his daughter in Antwerp, but she does not write back.

All Souls and All Saints: Cromwell takes a hammer to Geoffrey’s cell wall, and Geoffrey takes a blade to himself. The prisoner helps Lord Privy Seal complete his grid, exposing a vast conspiracy against the Tudor regime.

Meanwhile, Gregory’s old tutor Margaret Vernon comes to see him. ‘You are stouter, Thomas,’ she tells him. ‘You look as if you don’t get any fresh air.’ He thinks he could make her his wife. Rafe is surprised he hasn’t already a thousand wives. But it’s not worth it. ‘Nobody’s worth it.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Wyatt • Thomas Cromwell • Dick Purser • Anthony • Henry VIII • Robert Barnes • Cuthbert Tunstall • Lord Lisle • Lady Mary • Chapuys • Mendoza • Castillon • Philip Hoby • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Wriothesley • Hans Holbein • Gregory • Geoffrey Pole • Christophe • Stephen Gardiner • Richard Riche • Francis Bryan • William Fitzwilliam • Richard Cromwell • Martin • Margaret Vernon

This week’s theme: Deception and Disappointment

England has been deceived by both Emperor and France. Henry is furious. Nothing will console him but theology.

The feast of Corpus Christi takes place in early summer, sixty days after Easter. It celebrates the mystery of the Eucharist, the sacrament in which a Christian congregation consume bread and wine in remembrance of the Last Supper and the death and resurrection of Christ.

In the sixteenth century, disagreement over the nature of this ritual divided Christendom. Catholic doctrine upheld the belief that wine and bread actually became the body and blood of Christ during Holy Communion. Lutherans and other reformers argued that ‘transubstantiation’ was a lie; Holy Communion is an allegory and nothing more. Corpus Christi is a deception.

We are feeling deceived. Thomases Cromwell and Wyatt compare notes on ‘prince’s tricks’: the monarchs who make them wait; the kings who belittle and then shower you with gifts. Wyatt knows he is being watched. We all are. ‘Lock up what you write,’ Cromwell advises. ‘Prose or verse.’

Cromwell goes in person to disinter Thomas Becket, patron saint of all Thomases.2 He finds two skulls, and it would not surprise him ‘if that treacherous knave had six heads’. All those pilgrims, all those Canterbury tales, came to kiss a double deception: the skull of a saint that wasn’t a saint and it wasn’t his skull.

Meanwhile, the Poles and the Courtenays think they are deceiving Henry Tudor with their oaths of loyalty; Geoffrey in the Tower is deceived into thinking Lord Privy Seal really will break his legs. Cromwell keeps his distance from a Lutheran embassy pledging to make England head of their confederacy. They are deceiving themselves, he thinks. Henry will not make friends with Lutherans.

But what is friendship? It is a Ten-Minute Truce between wolves looking for weakness:

Wyatt thinks himself shrewd, but he does not grasp what friendship is, as the world goes now. Friendship swears it will stand and never alter, but when the weather changes men change their coat. Not every man has a price in money: some will betray you for a kind word from a great man, others will forswear your company because they see you limp, or lose your footing, or hestitate once in a while.

He, Cromwell, has a slight limp left over from his Italian fever. He hesitates occasionally, but they have not noticed. If he has lost his footing, he has found it again. He does not think himself deceived. His fool sits at his gate: ‘Anthony, I thought you were in Stepney.’

At Canterbury, a phantom coat floats through the air. He feels the cold, ‘from leaf-fall to Advent.’ The king complains they have all 4let him down. ‘Francis Bryan said he would trap Pole. But he has disappointed me. Like you, Cromwell.’

Like you.

Footnotes

1. The Truce of Nice

Our official reaction to the treaty is disbelief. Instead of the Ten-Year Truce we call it the Ten-Minute Truce.

Europe’s two great powers have been fighting over Italian territory, on and off, for the last forty years or more. On the one side is Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, united under Charles Habsburg. On the other, France: England’s eternal enemy. Early in the conflict, Thomas Cromwell fought as a mercenary in the French army. Now, in the late 1530s, France has become the first Christian country to ally with the Muslim Ottomans against the Holy Roman Empire.

Remember last week we learned about Christina of Denmark, Charles’s niece and widow to Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan? Francesco’s death allowed Charles to grab the Duchy of Milan in northern Italy. Thomas Wyatt tells Cromwell that Charles is offering Milan as a wedding gift if Lady Mary marries Dom Luis of Portugal.

‘But he will never give up Milan,' Wyatt says. 'Not this side of the Last Judgement.'

At Nice, François and Charles refuse to speak in the same room, and Alessandro Farnese, Bishop of Rome, is forced to mediate. The truce leaves Spain in control of much of Italy and Charles is free to turn his attention to the Ottomans.

Or towards England. ‘If the treaty lasts our peril is extreme,’ thinks Cromwell. The conquest of England by Spain allied with France would be ‘simple enough and cheap.’ And the threat focuses Cromwell’s mind on the enemies within: ‘the friends’ waiting for a foreign invasion: ‘Pole’s people’ and ‘the Courtenays.’

The Ten-Year Truce lasts longer than ten minutes, but doesn’t go the full decade. In 1542, Spain and France will once again be at war. On that occasion, the Emperor will be allied to Henry VIII, engaged in his final military confrontation with France.

But by then, Thomas Cromwell will be long gone.

2. Edmund Bonner

Thomas Wyatt does not mince his words when it comes to ‘that runt Edmund Bonner’ who is about to replace Stephen Gardiner as England’s ambassador in France:

'I would rather live in a rats' nest than lodge with him. I have never met a man so quick to take offence, and so quick to give it. He makes me sweat with shame. I do not understand why either you or the king would promote such a ball of tallow.'

Cromwell ‘is silent on that’ and that silence is an ironical ellipsis by Hilary Mantel. ‘Hindsight is a depressing gift,’ writes Diarmaid MacCulloch about the man who will be known as ‘Bloody Bonner’ for his persecution of Protestants during the reign of Mary I.

Bonner had been Cromwell’s friend since Wolsey’s days and had been with their former master at his arrest at Cawood and death at Leicester in 1530. Bonner has been a dutiful servant in the cause of royal supremacy over the church and the translation of the English Bible. He also hates Stephen Gardiner. Cromwell does not know that this enmity will not last.

Here, Thomas Wyatt is warning Cromwell but Cromwell does not hear. In fact, with a further ironical twist, Cromwell goes on to think about how Wyatt ‘does not grasp’ the nature of fair-weather friends who will ‘betray you for a kind word from a great man.’ And with one last layer of dramatic irony, Cromwell impresses this lesson of caution on Call-Me, Thomas Wriothesley, Gardiner’s protégé: the man with two masters.

3. Beavers from Danzig

'Not seen since our grandfathers' time. I want to breed them. Fishermen will be against it.'

Thomas Avery’s accounts tell us that Cromwell had ‘four live beavers from Danzig’ but we have no evidence that Cromwell planned to breed them or release them into the wild. He had a variety of exotic animals at his London residences, including a ‘strange beast’ in the garden – we will return to that later.

Thomas Cromwell did have a particular interest in riverways, weirs and waterworks. Like the enclosure of land for sheep farming, illicit waterworks were a flash point for conflicts between competing interests in Tudor England. At the start of the decade, Cromwell gave powers to sewer commissions to regulate waterways. Diarmaid MacCulloch quips that, ‘had he lived longer’ Thomas Cromwell may ‘have gone down in history as the Hammer of the Weirs’ instead of the Hammer of the Monks.

In medieval bestiaries, the beaver is often portrayed eating its own testicles while being pursued by hunting dogs. This is an allusion to the ancient fable attributed to Aesop in which the beaver relieved itself of its prized possession in order to preserve its life. The fable entreats us not to put ourselves in danger for things we can live without.

I couldn’t help but think Mantel was presenting an open question to Cromwell and us readers: What form of self-castration could save Cromwell now? We think we can save ourselves if necessary. Cromwell remembered Thomas More as the man who came clos to beheading himself. But in an earlier chapter, Cromwell mused that ‘He is not a snake who can slip his skin.’ Nor a beaver who can bite off his own balls?

Further reading:

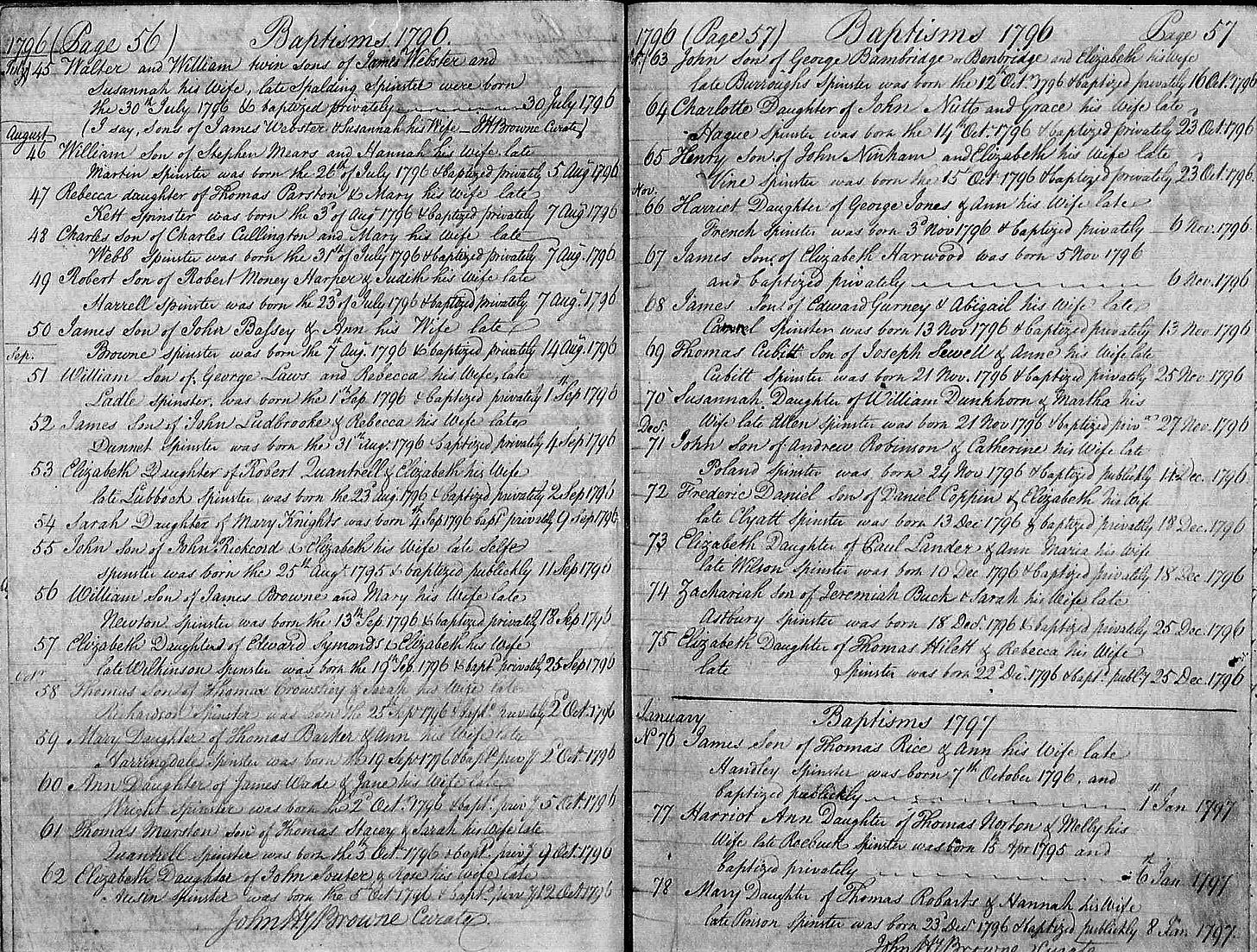

4. Parish Registries

In autumn, too, he brings in a way of counting people. Each parish must start a register to record baptisms, marriages and burials. From now on his countrymen will know who they are and where they come from, who their cousins are and what their grandfather was called.

In September 1538, Thomas Cromwell introduced parish registries in England and Wales. This small detail connects me and many of us back through time to this innovation by Henry VIII’s minister. Thanks to Cromwell we have this invaluable ancestral record reaching back into the sixteenth century.

Diarmaid MacCulloch speculates that a registry of baptisms was intended to identify those parishioners who had not been baptised. As we saw in Wolf Hall, Cromwell was on alert to stop Anabaptism from spreading to England. The radical sect that had briefly taken control of Münster not only rejected the idea of infant baptisms; they opposed all social authorities. Cromwell and Cranmer branded both monks and religious radicals as ‘sectaries’, dangerous to the social order.

5. Buried Alive

You sit down with his ambassadors, with Mendoza, with Chapuys; you pass a pleasant evening, you talk about books, you enjoy good food and a little music. But never forget: their regime buries women alive.

Cromwell and Cranmer burned Anabaptists. But across the Narrow Sea, the authorities in the Low Countries were burying heretics alive. Live burial was a punishment within the Holy Roman Empire for a variety of offences including rape, infanticide and theft. The last person to be executed for heresy in this manner was the Anabaptist Anna Utenhoven in 1597. Her death resulted in serious unrest in the northern provinces and the end of capital punishment for heresy.

Perhaps even more chilling than the idea of live burials, is the possibility that Cromwell considers this especially cruel and barbaric. After all, we have just sat through the gruesome immolation of John Forrest and we are about to stand uneasily by the door, as Cromwell feels the weight of a hammer in Geoffrey Pole’s cell.

6. The Last Fire

‘When the first candle is burned down, the bidding ceases. But then, who wants to make a hasty bargain? Buyer or seller, a man needs thinking time.3 A second candle is lit. There may be higher bids. When the second candle goes out the deal is done.’

‘Candle auctions’ became more popular in England in the seventeenth century, and John Milton and Samuel Pepys both recorded the practice of selling ‘by inch of candle’. Once again, Cromwell’s cosmopolitan knowledge of foreign practices puts him ahead of his fellow countrymen. His ways are strange to them and give the impression of the dark arts:

It seems the grid on the paper has filled the prisoner with dread. It makes no sense to him than a heptagram or other figure drawn by a magician.

This book is full of light; its capacity to illuminate and to burn.4 Time is running out for Geoffrey, for Cromwell, and for us. ‘When the last fire is done we will be in the dark. Then I will break your legs.’

Again, we return to the theme of bargaining for your life. ‘It is against his nature to think that no bargain can be struck.’ Cromwell lights the candles for Geoffrey but he must sense his own ‘last fire’ burning low. To Margaret Vernon, he compares himself to an overloaded sinking ship. At Canterbury, he feels ‘bone-weary’ from breaking up Becket’s shrine.

He hears the words of Robert Barnes, echoing in his head: ‘Suppose the king is losing his nerve?’

Quote of the Week: The beginning of the world

In the last chapter, Cromwell called Henry, ‘The mirror and the light of other kings.’ The title of the book comes from a piece of his correspondence which we will encounter in next week’s reading. Mantel said that one of her assumptions in writing dialogue was that phrases found on the record in the archive were probably rehearsed and fashioned first in snatches of conversation.

But that’s just the start of it. Metaphorical language doesn’t come out of nowhere. A writer finds it in the tug of their life: they absorb sensations, images and ideas that become language and words. These books root Cromwell’s world of words into a living England we can recognise because we have seen it ourselves.

So Hilary Mantel describes the Sussex Downs in evening light. It is something she saw, but could imagine Cromwell seeing. She lets it become part of his memory and imagines how it may have seeped into his language. His way of seeing:

Father and son ride out together in the evening, the sun a perfect crimson orb above the line of the downs. The sky has become a mirror, against which the sun moves: light without shadow, like the light at the beginning of the world. Gregory’s chatter stills; the creak of harness, the breathing of the horses, seems to muffle itself, so they move in silence, outlined against silver, tall against the sky; and as the upland fades into a pillowy distance, he feels himself riding into nowhere, a blank, where only memory stirs.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the second half of ‘Corpus Christi, June–December 1538’ and ‘Inheritance December 1538’. This runs from page 599 to 625 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “In the first week of November he arrests Lord Montague and the Marquis of Exeter.” It ends: “He is afraid it will answer back.”

If you are enjoying this slow read, please consider recommending it to others so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. You can now give your friends, or your enemies, the gift of Cromwell with an annual subscription to Footnote and Tangents.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Hilary Mantel thinking about her own work: ‘Some are young actors, not afraid of fresh plots, nor superstitious about putting new lines in the mouths of the dead.’

Last week, gravediggers. This week, a skull in our hands. Cromwell as Hamlet: “He turns up the skull between his hands. His fingers explore the calvarium. They emerge through the battered eye sockets. ‘Well – whence comes this second relic?’”

Note how this complements Cromwell’s advice to Rafe and Call-Me earlier in the chapter: ‘I urge you both, undertake no course without deep thought: but learn to think very fast.’

Light consumes but we dream of consuming it: ‘There is a pure, clean world, where men subsist on milk and apples, and bread so white and soft it is like eating light.’

Note: This chapter contains the second reference to the hidden memory from Cromwell's past. I won't draw attention to it just yet, but it is a fabulous easter egg for re-readers who haven't noticed it before.

Margaret Vernon: 'I shall set up housekeeping with some of my sisters. We shall be unruly women, with no master.' ... 'Folk will pity us and leave apples on our doorstep They will come to us for poultices and lucky charms.'

At least somebody in this chapter will be living the dream. ; )