Welcome to week 20 of War and Peace 2024. This week, we have read Book 2, Part 4, Chapters 5 – 11.

Everything you need for this read-along and book group can be found on the main War and Peace page of Footnotes and Tangents. There you will find:

The reading schedule with links to daily chat threads for each chapter.

Weekly updates like this one.

These resources are free for all, thanks to the generosity of paying subscribers who support my writing and this slow book group. Paid supporters have access to All Tolstoy’s parties: every ball and banquet, reviewed, rated and ranked. You can also start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Thank you so much for your support!

This is a long post, and your email provider may clip it. It is best viewed online here.

This week’s tangent: The enchanted forest

I wrote this piece during our read-along in 2023.

Listen to this tangent:

When did it all begin?

With the Wild Hunt? The devil riding out into the hoar frost. Odin and his valkyries. Forewarning the end of the world, or worse? Demons in their stirrups pulling down young hearts to the underworld.

Or with the Joyous Shriek? Natasha, death reflected in her eyes. Behind which, a thousand dull afternoons, waiting for life to begin.

By that shriek she expressed what the others expressed by all talking at once, and it was so strange that she must herself have been ashamed of so wild a cry, and everyone else would have been amazed at it, at any other time.

Because this isn't any other time. No other place. This is the enchanted forest, the fairy kingdom.

That's it, come on! We are not long here. Why struggle? Why fight? ‘Nothing will remain. Then why harm anyone?’

Come in. There's herb-wine and vodka, pickled mushrooms, rye-cakes, sparkling mead and nut-and-honey sweets.

Warm your soul by the fire. Raise the cup to your lips. And dance, dance. Dance!

Tonight she is happy. Not happy as she was at the ball – a gift for men she hardly knew. A world that hardly cared. But happy in herself and in her soul. ‘No, I'm quite, quite all right. I feel so comfortable!’

Tonight, brother and sister ride together through Fairyland. The air is cold but deep with magic. Growing up means forgetting to dream. You marry an heiress and you stop shrieking for joy.

But tonight, we're young again. And remember other ways to live and dance and love. The mummers come. He puts on a dress. Sonya takes burnt cork and draws on a moustache.

It seemed to him that it was only today, thanks to that burnt-cork moustache, that he had fully learnt to know her.

Because we need crazy nights like these, where the world turns at full tilt. The sky is dark and the earth is gay.

‘Quite different and yet the same.’ Crossdressing moonlit kiss, outside a barn where some phantom tells the future.

This magic cannot last. The dance must stop and the chalk will fade.

But let no one say it didn't happen. Let no one say it wasn't real.

We danced. We kissed. We laughed. We shrieked. We were happy then.

Chapter 5: To get an old wolf

Nikolai waits at his post for the wolf to appear. He prays to God to grant him this one piece of luck. The wolf comes and Nikolai releases his dogs. He considers this the happiest moment of his life. Briefly the wolf escapes before being cornered by Uncle and captured by Danilo. Her cubs are killed and she is taken to show the others.

Nikolai • Danilo • Count Rostov • Uncle

Wild reading

The hunting chapters of War and Peace can be difficult for modern readers. Our sensibilities and sensitivity to animal cruelty can take over and get in the way of a broader appreciation of the brilliant writing on these pages. And perhaps the vivid and immersive way in which Tolstoy writes does not exactly help. He compels us to live these moments and feel every second, first from the perspective of the hunter, and then the dog, and then the wolf. Whatever we feel, we feel it with an immediate and tenacious intensity. These are wild chapters and require wild reading.

Suddenly the wolf’s whole physiognomy changed; she shuddered1, seeing what she had probably never seen before—human eyes fixed upon her, and turning her head a little towards Rostov she paused.

In a draft version of the novel’s epilogue, Tolstoy wrote: ‘The hunt is described so seriously, precisely because it is equally important.’ Contemporary critics felt it superfluous to the plot, modern readers find it gratuitous. We might not accept it as a description of sport or play, but Tolstoy wrote it as an unreserved, unflinching portrayal of the joy and full experience of living. In its essence it conveys the heart and soul of War and Peace. As Andrew Kaufman writes2:

You almost feel as if, rather than reading a work of fiction, you were experiencing, in Matthew Arnold’s apt description of Anna Karenina, a “piece of life … The author has not invented and combined it; he has seen it.” And heard, touched, smelled it—all of it. In these pages there is brutality and bloodiness and beauty almost beyond words. There is unbearable rightness of being. This, Tolstoy is saying, is what it feels like to live in the now.

How does Nikolai’s behave differently on the hunt compared to in battle?

Chapter 6: Natasha’s shriek

The count goes home, and the hunting party chase a fox. A rival hunt led by Ilagin takes the fox and Nikolai expects a fight. But Ilagin is courteous and friendly and the two hunts join together to chase hares on Ilagin’s uplands. The rivals race their expensive dogs but are both beaten by Uncle’s borzoi. In the confusion, Natasha lets out a wild, joyous and ecstatic shriek.

Natasha • Nikolai • Petya • Uncle • Ilagin

On happiness

If some of us struggle with the cruelty, others scratch their heads at the rivalry. I’m one of those readers. I’m not a competitive person. I always tried to get out of sports at school and have never really got my head around the passion of partisanship, of watching and taking part in the big game. I know this may be my handicap and possibly an impediment to my own happiness. I think Tolstoy might have thought so. Because this chapter is all about the thrill of the chase. At its climax, Uncle explodes with delight at his dog’s performance and Natasha lets out a glorious, joyous shriek. Kaufman again:

Uncle is in touch with a joy of living so visceral and truthful that it merges with disgust, pride, exhilaration, revenge, and a whole host of other feelings. Here is life at its rawest and most real, like something of Homer’s Iliad, a book that Tolstoy loved and read often, and to which he on one occasion proudly compared War and Peace. Natasha, sensing the intense energy of this moment, expresses its wild, epic thrill, not through words, but through “a joyous and rapturous shriek.”

In a way, I am indebted to Natasha’s shriek. For what I struggle to fathom in Nikolai, Ilagin and Uncle, I somehow understand in Natasha. For sometimes happiness comes upon us with such a wordless intensity, it can only be expressed in an explosion of sound.

Jeffrey Morris in Yiyun Li’s Tolstoy Together:

Natasha’s uncanny shriek during the hunt. What do you hear in it? I hear fresh air, exercise, and, just maybe, liberation from the suffocation of ballrooms, talk of money, talk of marriage, and marrying for money!

So what do you hear in Natasha’s shriek?

And are you competitive? When do you feel most happy and most alive?

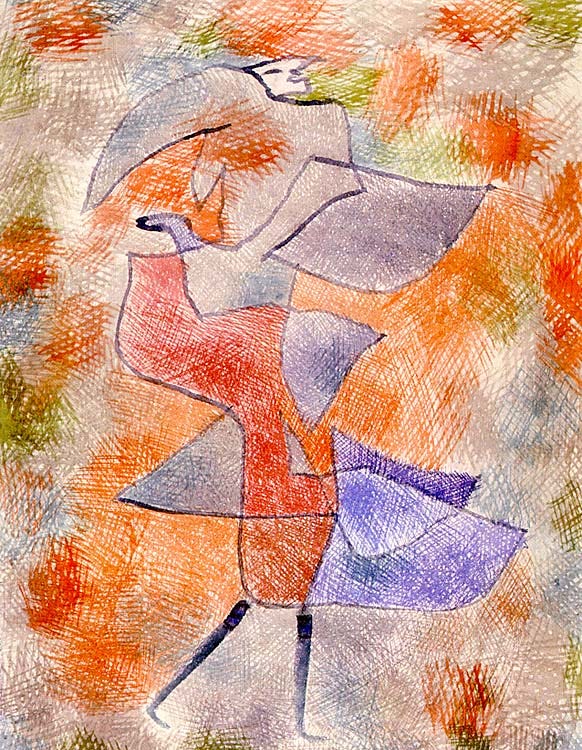

Chapter 7: Natasha’s Dance

Uncle invites them back to his cabin, where his housekeeper lays on a feast, and his coachman Mitka strikes up a tune on the balalaika. The siblings are children again and are swept up by the enchanting atmosphere. Uncle plays his guitar, and Natasha dances a folk dance perfectly. On the ride home, they laugh and sing, happy and in love.

Natasha • Nikolai • Petya • Uncle • Anisya Fyodorovna • Mitka

Thank you to

for find the music featured in this chapter. Mitka is playing the air of My Lady on the balalaika. You can listen to it here:On the guiter, Uncle plays Came a maiden down the street, which you can listen to here:

And here is the song to which Natasha dances, called ‘Like a powder evening’:

And finally, here is this scene in the 2016 BBC dramatization of War and Peace:

Uncle’s paradise

So we have come to one of my favourite chapters! Uncle’s house, full of fabulous food, music and dance. We see Uncle at rest. He has renounced public life for private pleasure, happiness and peace of mind. ‘Nothing will remain. Then why harm anyone?’ We meet the lovely Anisya, who at forty is ‘stout, rosy, good-looking’ (yes, you can be forty and beautiful in War and Peace). Her face says: ‘Here I am. I am she! Now do you understand Uncle?’

My favourite part of this chapter is the dynamic between brother and sister. Natasha lets Nikolai shake off all that silly manly posturing and be a child again. They can’t stop laughing. When he says it is excellent, she corrects him: ‘it’s simply enchanting.’ On the ride home, they enter into each other’s fantasies, Uncle is a dog and Rugay is a man. They are bound together to Fairyland. Under this enchantment they, and us, would like to hold the page and stop time. ‘Why should she marry?’ Why must Nikolai return to war? ‘We might always drive about together!’

This chapter is very famous for Natasha’s dance, and Orlando Figes thought it so consequential that he titled his cultural history of Russia, Natasha’s Dance. Here are a few quotes from the introduction of that book:

What enabled Natasha to pick up so instinctively the rhythms of the dance? How could she step so easily into this village culture from which, by social class and education, she was so far removed? Are we to suppose, as Tolstoy asks us to in this romantic scene, that a nation such as Russia may be held together by the unseen threads of a native sensibility? …

[This scene represents] … the writer’s yearning for a broad community with the Russian peasantry which Tolstoy shared with the ‘men of 1812’, the liberal noblemen and patriots who dominate the public scenes of War and Peace …

At its heart is an encounter between two entirely different worlds: the European culture of the upper classes and the Russian culture of the peasantry. The war of 1812 was the first moment when the two moved together in a national formation. Stirred by the patriotic spirit of the serfs, the aristocracy of Natasha’s generation began to break free from the foreign conventions of their society and search for a sense of nationhood based on ‘Russian’ principles. They switched from speaking French to their native tongue; they Russified their customs and their dress, their eating habits and their taste in interior design; they went out to the countryside to learn folklore, peasant dance and music, with the aim of fashioning a national style in all their arts to reach out to and educate the common man.

What would Andrei think of Uncle and this way of life?

What have you learned about Nikolai and Natasha in the last five chapters?

Chapter 8: The entangled net

Back at Otradnoe, the Rostovs have very unsuccessfully tried to downsize. There appears to be only one solution to their financial woes: Nikolai must marry the rich heiress Julie Karagina. He and his mother argue about it, and Nikolai grows closer again to Sonya. In Rome, Andrei’s wound has re-opened, and Natasha falls into a depressive state, feeling sorry for herself and the time she has wasted.

Nikolai • Countess Rostova • Count Rostov • Natasha • Sonya • Julie Karagina • Andrei

‘But, Maman, suppose I loved a girl who has no fortune, would you expect me to sacrifice my feelings and my honour for the sake of money?’ he asked his mother, not realizing the cruelty of his question and only wishing to show his noble-mindedness.

Tolstoy deftly packs a lot of complexity into one line:

Why is his question cruel? What do we know about Countess Rostova’s past and present relationships that add a sting to Nikolai’s talk of love and money?

Is Nikolai noble-minded? Or does he just wish to be so?

I think it is useful to compare his thoughts and behaviour here, especially towards Sonya, with his performance as a homecoming hero after Austerlitz:

On his return to Moscow from the army Nikolai Rostov was welcomed by his home circle as the best of sons, a hero, and their darling Nikolushka, by his relations as a charming, attractive, and polite young man, by his acquaintances as a handsome lieutenant of hussars, a good dancer, and one of the best matches in the city.

What has changed? And why?

Chapter 9: The Queen of Madagascar

It is Christmastide, and the house should be full of festive joy. But for Natasha, everything feels dull and the same. She takes out her tedium on the servants and behaves like a capricious tyrant in her island kingdom. ‘Oh, if only he would come quicker!’ she says. ‘I am so afraid it will never be!’

Natasha • Nikolai • Sonya • Count Rostov • Countess Rostova • Petya • Nastaya Ivanovna

‘No, it’s the chorus from The Water-Carrier, listen!’ and Natasha sang the air of the chorus so that Sonya should catch it.

The Water-Carrier is an opera in three acts by the Italian-born French composer Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842). It was first performed in 1800 in Paris and you can listen to it here:

This chapter reminds me of the opening section of Part Four, where Tolstoy describes the blessed idleness of the Garden of Eden, and its re-creation in military life. These last few chapters deal with different responses to leisure and the art of doing nothing. Countess Rostova has his patience, Sonya has her embroidery, Uncle has his untidy garden, his guitar and his quiet life. Nikolai and Natasha struggle in their own ways to find happiness at rest. Both are young and restless, in search of novelty, romance and adventure!

Have you experienced monotony and boredom like this? If so, when? And what did you do to cope?

On divination

In the next few chapters there are several references to predicting the future. Thanks again

for explaining one of them here:[Natasha requests] a rooster and some oats, a tradition tied to Christmas divination. A rooster is brought from the chicken coop, provided with grain and water. If the rooster pecks at the grain before drinking, it predicts a prosperous married life for the girl. However, if it drinks first, it indicates the future husband will be a drunkard.

And the buffoon makes a prophecy of sorts:

'Nastasya Ivanovna, what sort of children shall I have?' she asked the buffoon, who was coming towards her in a woman's jacket. 'Why, fleas, crickets, grasshoppers,' answered the buffoon.

This is ‘an oddly thrilling exchange,’ writes Yiyun Li in Tolstoy Together. ‘She’s fluent in nonsense. He, with an etymologist’s mind, is an nimble-witted as King Lear’s clown.’

Chapter 10: The Enchantment

Nikolai and Natasha share ‘poetic, youthful’ memories, while Sonya struggles to keep pace. Natasha sings and Petya announces the mummers. They all dress up and set off to one of their neighbours. Sonya’s costume awakens something in her and as they ride across a new and enchanted meadow, Nikolai discovers he is in love with the Circassian with the burnt-cork moustache.

Nikolai • Natasha • Count Rostov • Countess Rostova • Petya • Sonya • Dimmler • Madame Schoss

‘Mr Dimmler, please play my favourite nocturne by Monsieur Field,’ came the old countess’s voice from the drawing room.

John Field (1782–1837) was born in Dublin and settled in Russia in 1804. Known as ‘Russian Field’ he is credited with the invention of the nocturne, a musical composition inspired by, or evocative of, the night. You can listen to his 18 nocturnes here:

‘If we have been angels, why have we fallen lower?’

This chapter is extraordinary! Ever since the wild hunt and the joyful shriek, reality seems to have slipped from its axis. Uncle’s guitar is still humming in our ears, Natasha’s feet drumming the floor. Brother and sister circling each other with memories.

‘Did you know,’ said Natasha in a whisper, moving closer to Nikolai and Sonya, ‘that if you just go on and on recalling memories, at last you’ll begin to remember what happened before you were in the world…’

And now the mummers come, the troikas and the moonlight. Enchantment and transformation: ‘This used to be Sonya… This used to be Natasha…’

But here was a fairy forest with black moving shadows, and a glitter of diamonds and a flight of marble steps and the silver roof of fairy buildings.

What do you make of Natasha and Nikolai’s childhood memories?

What are your earliest shared memories?

When has an item of clothing changed who you are and how you feel?

Chapter 11: The empty bath-house

At the Melyukova house, the mummer party dance and play games. Nikolai does not leave Sonya’s side. They stay for supper and learn of the empty bath-house where you can hear your fortune. Despite or because of the ghost stories, Sonya asks to go. Nikolai follows her out the house and meets her on the path. They kiss and embrace, go to the barn and return, separately, to the house.

Sonya • Nikolai • Natasha • Melyukova

They were quietly dropping melted wax into snow and looking at the shadows the wax figures would throw on the wall…

The mummers are intruding on a bored bit of divination. More fortune telling, this time with melted wax. Followed shortly by a ghostly visit to the bath-house.

Outside there was the same cold stillness, and the same moon, but even brighter than before. The light was so strong and the snow sparkled with so many stars that one did not wish to look up at the sky and the real stars were unnoticed. The sky was black and dreary, while the earth was gay.

A mysterious barn where a man tells your fortune. Two cross-dressing lovers in the moonlight. Let’s all agree: Nikolai looks good in a dress. Sonya rocks that moustache. Burnt cork never smelt so sexy. Here is another chapter you want to climb inside and never leave.

What have you learned about Sonya in these last few chapters?

Have you ever tried to divine the future?

Have you ever been to a fairy forest? Or lived through an enchanted night?

Thank you for reading

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of War and Peace.

A quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus reviews of all the parties of War and Peace and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. You can also donate to my tip jar on Stripe. Thank you so much for all your support.

And that’s all for this week. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Have a great week, and I’ll see everyone here next Sunday for more War and Peace 2024.

Translation note: In the original Russian, the wolf is male. This has been retained in the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation. But Anthony Briggs and the Maudes decided to make the wolf a mother with cubs. It’s a curious switch that seems to me designed to elicit greater sympathy from the reader – I would be interested if anyone can shed light on this translation decision.

In Give War and Peace a Chance: Tolstoyan Wisdom for Troubled Times. Chapter 6. Happiness.

This is my comment of gratitude for the article. I just listened to your prose, and I'm already delighted, Simon.

Honestly, I have a very complicated relationship with Tolstoy, I hated him at school, then at the university (I studied philology and international journalism, where Russian literature was taught for 4 years). And there was such a stereotype at the university that you can truly love either Dostoevsky or Tolstoy. Both are impossible, because they are very different and determine your literary taste. And I was in Dostoevsky's clan. But now, thanks to this slow reading, I gave Tolstoy a chance, and I start to like him… He has so much stuff to dig through references and references.

“For sometimes happiness comes upon us with such a wordless intensity, it can only be expressed in an explosion of sound.” Beautiful, thank you, Simon 🥰