This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to week 31 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the first section of ‘Salvage, London, Summer 1536’ This runs from page 27 to page 77 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘Where is my orange coat?’ It ends: ‘…feeling as if for the first time the beat of his own heart.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

It is the last day of May. He puts on an orange coat he has not worn since the cardinal came down, and goes to court to congratulate the newlywed royal couple of England.

The king shows his gratitude: he is to be Lord Baron Cromwell of Wimbledon and Lord Privy Seal. It is the morning of a new world; Henry Tudor has ‘come out of Hell into Heaven, and all in one night.’ Jane Seymour is mobbed by her family and keeps them guessing.

Power is reshaping itself at court: Boleyns out; Howards, twitching. Chapuys takes notes; Nicholas Carew reminds Cromwell of their bargain, and he, Cromwell, touches his hand to his heart and to the coat pocket that conceals the knife.

In the king’s privy chamber, Henry is doubting what he’s done. ‘Did I do right?’ he asks Master Secretary. Cromwell listens to the king talk of curses, his own death and the rule of queens; all things Henry Tudor fears. The king asks him whether he sleeps at night, and where he comes from. ‘Putney, Majesty,’ he replies, usefully.

Outside, Charles Brandon thrusts out his vast hand. Suffolk wants to be friends. He wants his king to sleep easy at night. We all want that: to press on, move forward and never look back.

At Austin Friars, he removes his orange coat and goes to see the cook. Thurston is laying into Matthew of Wolf Hall, who has come to learn accounts and not to kill eels. He, Cromwell, can do both. Thurston gives him the gossip. It’s nothing he doesn’t already know.

Supper with Chapuys. Eel served two ways. If Cromwell helps Mary back into the line of succession, it will be for a German alliance and his own neck, not for Nicholas Carew and the old families. The two men remember Italy and the ravioli.

He will send Call-Me and Rafe to Lady Mary to prepare her for a reconciliation with the king. Call-Me is jittery – when is he not? – and spooked by the whispers and stares at court. He, Lord Cromwell, retires to his rooms, with Christophe and then with his thoughts.

At night, he cannot sleep: he counts money in and money out. He counts clerks and Howards, bodies and heads, and Anne’s four waiting women about his bed. He remembers her brother George in the Tower, rehearsing the fear he will hide from the world on the scaffold. He remembers his wife and her last stitch in a cushion cover, a deer running away.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Christophe • Gregory • Richard Cromwell • Thomas Wriothesley • Henry VIII • William Fitzwilliam • Eustache Chapuys • Jane Seymour • Margaret Douglas • Mary Fitzroy • Lady Margery • Edward Seymour • Tom Seymour • Nicholas Carew • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Howard the Lesser • Charles Brandon • Thurston • Matthew • George Boleyn

This week’s theme: Hand on heart

Last week, Thomas Wriothesley hoped the Cromwells would know how to distinguish their friends from their enemies. He, Thomas Cromwell, reminded himself that Uncle Norfolk is not our comrade. ‘He is slapping us to appraise how solid we are.’

This week, this theme of sizing up our dangerous allies continues. Sir Nicholas Carew ‘heaves’ his ‘plush frontage’ into Cromwell’s way, reminding Master Secretary that ‘We made a bargain with you.’ We, the old families of England, the Poles and Courtenays, the friends of Princess Mary.

He doesn't answer Carew, merely adjusts him so that his path is clear. Passing him, he touches his hand to his heart. It looks like the gesture of a man suddenly anxious. But that's not what it is, and that's not what he's doing.

What he is doing is revealed a few pages later when he is safe at home in Austin Friars. His hand goes to his heart, and he removes the knife, concealed in the pocket inside his jacket.

'Still?' Richard says. 'Even now?' 'Especially now.' Without the weight next to his heart, he would hardly know himself.

Richard tells his uncle that he ‘cannot imagine the circumstances in which you could use it.’ It is a grave offence to spill blood in the proximity of the king, the punishment being the removal of the offending limb. Cromwell remembers his first blade, the one Hilary Mantel called an ‘evil tooth’ to kill Cornish rebels. ‘That was a good blade,’ he thinks, ‘and he misses it every day.’

At dinner with Chapuys, he recalls the moment in January when he picked up the Turkish dagger with the sunflower handle, when he heard the king was dead. What Mantel reveals here, which was hidden from us in Bring Up the Bodies, is that he already had another knife in his coat. We learn that during his ‘third life’ in Italy, he ‘carries a knife but keeps it in his coat.’ It appears he has always carried a concealed weapon since our story began. What else has he hidden from us?

Now we live in an age of cocercion, where the king’s will is an instrument reshaped each morning, as if by a master-forger: sharp-pointed, biting, it spirals deep into our crooked age.

A few pages on, he considers how he serves a king whose lies are ‘so deep and subtle he does not know he is lying; he thinks he is the most truthful of princes.’ Ambassadors turn to him, Cromwell, to discern the truth. He is the mirror to the king’s light, and ‘he puts his hand on his heart,’ and says, ‘By my faith.’

And there lies the cunning beauty of the gesture. The hand on the heart is a sign of sincerity, or its performance. It may signal fear, as he might like Carew to think he is afraid. Or it may give him strength, as he reminds himself of the knife he carries within.

Truth will slip away from us in this world beyond May 1536. As Chapuys observed, Cromwell’s imagination ‘is the most powerful in England’: he can dream other men’s treason into existence. He knows the gentlemen in the Tower were not guilty, but Tom Wyatt’s evidence was kept private, along with the reason for the annulment of the king’s marriage: ‘The truth is so rare and precious that sometimes it must be kept under lock and key.’

Cromwell is midwife to a post-truth era at Henry’s court. And we know the dangers of this fact-free existence in our own age. One who works in rumour and conspiracy, may soon enough become their victim. No wonder, then, Cromwell listens keenly to what they are saying about him behind his back:

He admires these speculative worlds, that grow up in the crevices between truths.

Everything points now to a dangerous time, where it pays to carry two blades and neglect no precaution. Austin Friars is now a fortress, ‘walled and guarded’, with gaps on either side of its inner doors, so an intruder may be simultaneously stabbed and shot. Thurston thinks it excessive. Cromwell disagrees.

‘The times being what they are, a man may enter as your friend and change sides while he crosses the courtyard.’

Footnotes

1. Coats of many colours

‘Where’s my orange coat?’ he says. ‘I used to have an orange coat.’

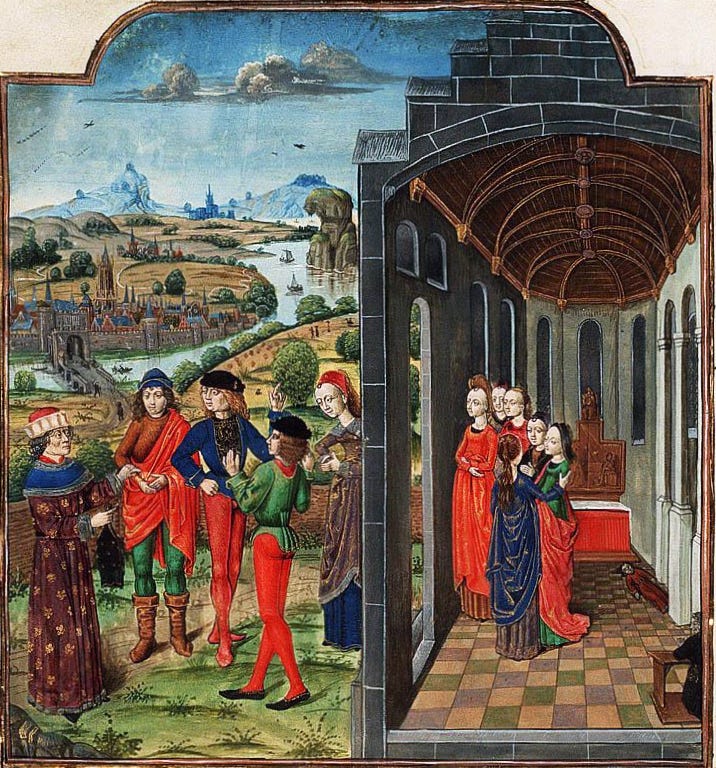

Let’s move away from the knife in the coat, to the coat itself. Clothes matter in these books, and colour is the mark of status, allegiance and intent. Sumptuary laws constrained what you could wear based on your office and position in society. Only the king and his family could wear purple. When Anne became queen, he, Cromwell ‘went into crimson.’ When her predecessor died, she celebrated in yellow. Now, she is dead, and he will wear orange.1

Thomas Wriothesley, son of heralds, is quick on the uptake: this is the livery of the late cardinal. He had no heart for it before, but now he is ‘feeling cheerful’. He is also feeling triumphant, and his coat is a blazing banner of Wolsey reanimated and returned to vanquish all his enemies. At home, he takes it off.

In the dimness of the room, shuttered against the afternoon, it blazes as if he handled fire. There are certain miserable divines, in darker days than these, who said if God had meant us to wear coloured clothes He would have made coloured sheep. Instead, his providence has given us dyers, and the materials for their craft. Here in the city, amid dun and slate, donkey’s back and mouse, gold quickens the heart; on those days of grey swilling rain that afflict London in every season, we are reminded of Heaven by a flash of celestial blue. Just as the soldier looks up to the flutter of bright banners, so the workman on his daily trudge rejoices to see his betters shimmer above him imperial purple, in silver and flame and halycon against the wash of the English sky.

This passage does a few things rather beautifully. Anyone in England knows those colourless days. We know what it means to see light illuminate life, and we invest a great portion of our hopes, longings and desires in the possibility of colour. To be English is to live in grey and look for rainbows.

Cromwell has felt gold quicken his heart. He’s been that city mouse, the workman on his daily trudge. But what he perhaps forgets in his triumph is that men do not rejoice to see their betters shimmer in purple. We are not generous in spirit; the English see red in rage and green in envy; we are spite, and we are malice.

Further reading:

Take a look at Robert Dudley's sleeves for an example of love knots, the pattern worn by Jane Seymour in this chapter.

An overview of sumptuary laws during the reign of Henry VIII.

2. Cromwells in our new Eden

But let us return to the England of our dreams.

For this is England, a happy country, a land of miracles, where stones underfoot are nuggets of gold and the brooks flow with claret. The Boleyns' white falcon hangs like a sorrow sparrow on a fence, while the Seymour phoenix is rising. Gentlefolk of an ancient breed, foresters, masters of Wolf Hall, the king's new family now rank with the Howards, the Talbots, the Percys and the Courtenays. The Cromwells – father, son and nephew – are of an ancient breed too. Were we not all conceived in Eden? When Adam delved and Eve span / Who was then the gentleman? When the Cromwells stroll out this week, the gentlemen of England get out of their way.

The verse When Adam delved belonged to one of England’s most famous rebels: the priest John Ball, a prominent participant in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Here, Cromwell is the pugnacious rebel rising, levelling the land against lords and gentry. But we are only a few months away from the Pilgrimage of Grace, the most serious uprising of Henry VIII’s reign. Those rebels will want to tear Cromwell down, who they believe is delivering England not into Eden, but into Hell.

John Ball’s verse was commonly known and reproduced in the sixteenth century and beyond. It would later be used by radical movements such as the Levellers and the Diggers. In Hamlet, Shakespeare has the gravediggers discuss its meaning: Was Adam a gentleman? asks one.

First clown: He was the first that ever bore arms. Second Clown: Why, he had none. First Clown: What, art a heathen? How dost thou understand the Scripture? The Scripture says 'Adam digged:' could he dig without arms?

3. The Mirror and the Light

In Wolf Hall it was the play. In Bring Up the Bodies it was the chase. The metaphor that holds together the third novel is the mirror: reflected light; the image doubled; the world reversed.

He thinks of Wyatt in his prison, as dusk slips through the runnels and esturaries of the Thames, where the last light slides like silk, floating, sinking; it is the light that moves, when the stream is still. Wyatt seems distant to him, as if held in a mirror; or as if he had lived a long time ago.

In the coming weeks, we will have plenty of opportunities to explore all the meanings of mirrors. When the king ‘draws him into a window embrasure’ to promote Cromwell to the House of Lords, he sees ‘small rainbows flit and dance across the stonework.’ As we have already seen, colour is status, and colour is nothing but reflected light.

And we need not be in any doubt who is the source of all light in England. Cromwell’s next job is to bring Mary into ‘the light of’ the king’s presence2. ‘Princes’, he tells the ambassadors, ‘are not as other men.’

They have to hide from themselves, or they would be dazzled by their own light. Once you know this, you can begin to erect those face-saving barriers, screens behind which adjustments can take place, corners for withdrawal, open spaces in which to turn and reverse.

My advice as we go forward: watch the light. Pay attention to reflections and to shadows and the things that move there. It is what Cromwell is doing. The future is the Medusa: ‘you cannot look in her face. You must trap her image in polished steel. Gaze into the mirror of the future: the unspotted glass, specula sine macula.’ The perfect mirror.

4. New characters: Tom Truth, Meg Douglas, Matthew

I would like to draw your attention to three new characters, and I am relieved to say that only one is called Thomas.

Unfortunately, he is another Thomas Howard, half-brother of Thomas Howard, Uncle Norfolk. Hilary Mantel reassures us,

No danger of confusing the two. The Lesser is the worst poet at court. The Greater never rhymed in his life.

As a poet, he goes by the name of Tom Truth, another way in which the theme of truth and its manipulation will resurface in the story.

Waiting on Jane Seymour are two ladies. One is Mary Fitzroy, Norfolk’s daughter. Richmond has spoken several times to Cromwell about his young bride. But the second lady is new to us:

Meg Douglas is a pretty lass, nineteen or twenty now. She stands up with a flash of red hair, and steps back to her place. Her hood is the French style that Boleyn favoured, but most of the ladies have reverted to the older sort, concealing the hair.

Margaret Douglas is Henry VIII’s niece and will be grandmother to James Stuart I and VI, King of England and Scotland. Now that all of Henry’s children have been declared illegitimate, she is high in the line of succession. The prospect of a woman ruling England weighs heavy on Henry’s mind:

‘I ask you – a woman, weak in body, weak in will – can she rule, with all the frailty of her sex? No matter if she is blessed with firmness, with nimble wit – still the day comes when she must marry, and bring in a foreigner to share her throne – or else exalt a subject, and who can she trust?’

This question will play out for both Henry’s daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I. More imminently, it will be of grave concern for Henry and Cromwell when Margaret Douglas chooses her husband.

Finally, there is Matthew, Cromwell’s new servant from Wolf Hall. Almost all the characters in the trilogy are based on real historical people. Christophe is one of the exceptions; and so is Matthew, who is named after a member of the cast of the stage adaptations of the novels. I felt Christophe was almost aggrieved to make space for Matthew in Mantel’s imagination, deploring ‘the ridiculous Matthew. I hear he is promoted.’

Matthew supplies Cromwell with another lost boy; another protege. His accidental apprenticeship in Thurston’s kitchen allows Mantel to nimbly retrace Cromwell’s own ascent from kitchen to countinghouse in the house of the Frescobaldi. He, and we, hear again the fountain drumbeat and the singing refrain: Scaramella off to war. It is one of his more happy, hopeful memories.

5. He, Lord Cromwell

With Anne out of the way, Thomas Cromwell’s route to the top lies open and unobstructed.

Now he becomes Baron Cromwell of Wimbledon. ‘He cannot call himself Lord Cromwell of Putney,’ he muses at the end of Bring Up the Bodies. ‘He might laugh.’ But Putney was part of the manor of Wimbledon, and in assuming the lordship, Cromwell reaffirmed his natal connection while acquiring some prime real estate. As Diarmaid MacCulloch writes:

This assumption of a title from Wimbeldon was a statement that the Putney boy had come a long way: a symbolic return of the native.

He declines the opportunity of creating a fictional lineage with Ralph Cromwell of Tattershall Castle and reasserts his link to Putney, Walter Cromwell and his other father, the cardinal. He will keep Wolsey’s choughs on his shield.

All of this is designed to offend the noble establishment of England, and especially the arch-snob himself, Uncle Norfolk.

Cromwell also acquires the Privy Seal from the outgoing Thomas Boleyn. This is the king’s personal seal, distinct from the Great Seal of England kept by the Lord Chancellor, Crumb’s mate Thomas Audley. This is Cromwell’s highest promotion to date and consolidates his position as ‘the second man in England.’

6. The nine lives of Thomas Cromwell

His sixth life was as Master Secretary, the king’s servant. His seventh, Lord Cromwell now begins.

I never noticed this before. Last week, Cromwell was the Damascene cat. So, of course! Thomas Cromwell has nine lives. He has entered his seventh. Will we decipher the other two, or has Mantel kept the analogy loose and the metaphor mercurial?

Where does this phrase come from? In Romeo and Juliet, Mercutio asks Tybalt, ‘good king of cats’, for ‘one of your nine lives.’ An English proverb runs: ‘A cat has nine lives. For three he plays, for three he strays and for the last three he stays.’ But Cromwell, king of cats, strayed in Italy and Antwerp, and returned for lives five through to seven.

So much for proverbs. And anyway, Cromwell’s personal tragedy is he never gets to life his last life.

7. The curse

Already, the end walks with us:

We shall not escape these weeks. They recapitulate, always varied and always fresh, always doing and never done.

On the one hand, Cromwell has begun his seventh life. On the other, there are only two worlds: the time before and the time after Anne’s head came off. He now thinks of last month as ‘the old days’, and at night, he and his king dream over and over…

Ah, he thinks, you see her too: Ana Bolena with her collar of blood.

Henry asks him, innocently, ‘Do you sleep at night, Crumb?’ But he does not, he cannot. He counts his money and the king’s money and the king’s men and his. William Stump? ‘Who could forget Stump… Get out of my dream, Stump.’

The four women who attended Anne at her death appear to him about his bed. They are veiled, so he does not know their names. ‘Lady Kingston, he thinks, would tell me who those women were. But must I know?’ The only things he cannot remember are the things he never knew.

They ‘swaddle that gasping head in cloth’. Gasping? ‘At his feet, eels are swimming in a pail, twisting and gliding; interlacing in their futile efforts, as they wait to be killed and sauced.’ Wait to be killed?

He remembers George Boleyn, sobbing, his young, strong arms, ‘springing with life’ locked around him, ‘as if grappling with Death.’ George asked him: ‘… can you explain it to me, Master Cromwell? How I am alive and dead at the same time?’

He cannot, although that is how we feel when we read The Mirror and the Light. Acutely alive, inescapably dead. We shall not escape these weeks.

The Haunting of Wolf Hall

You can read more on the spectral and fantasmal in this week’s bonus post:

Our Crooked Age

This is a bonus post for paid subscribers to accompany the weekly discussion post of the Cromwell trilogy by Hilary Mantel. It is part of a series exploring spectral and haunting themes in the Cromwell trilogy. You can read all of them here.

Quote of the week: History inks the skin

Cromwell once told himself that he never backs off. He never hesitates. He tells the king, ‘Go forward, sir. It’s the one direction God permits.’ He, Cromwell, finds himself walking towards, ‘always towards the king, his naked hands held out, no weapon.’

But at night, he takes the knife, and memories pull him back and down into the ‘subsoil of himself.’ The more we push on and up, the further down we must go.

History inks the skin: it writes on the hide of sheep long slaughtered, or calves who never breathed; the dead cut away the ground beneath us, so that when he descends a stair at Austin Friars, the tread falls away under his foot, and below him there is another stair, no longer visible except in the mind’s eye; and down it goes, to the city where the legions of Rome left their ashes beneath the earth, their glass in the soil, their bones in the river. And down it plunges and down, into the subsoil of himself, through France and Italy and the pays bas, through the lowlands and the quicksands, by the marshes and meadows esturine, through the floodplains of his dreams to where he wakes, shocked into a new day: the clang of the anvil from the smithy shakes the sunlight in a room where, a helpless child, he lies swaddled, startled from sleep, feeling as if for the first time the beat of his own heart.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we start the second section of ‘Salvage, London, Summer 1536’ This runs from pages 77 to 116 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘In his room at the Tower, Thomas Wyatt is sitting at the table where he left him…’ It ends: ‘…his burdened and oppressed flesh the place where all arguments come to rest.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

The orange coat appears in an inventory of Cromwell’s possessions on 16 June 1527. This list includes 'an outside of a cushion, needlework, wrought with an antelope.’ Mantel refers to it here as Liz’s final piece of embroidery.

See also: ‘In the shifting twilight, shadowed like water, he can see a figure of the king’s daughter: huddled into herself, her face pale and set. It entrances him, the stealthy movement of the light where she forms herself, a living ghost.’

God, I love Margery Seymour:

'Lady Margery’s glance stabs the old dames. None of them have kept their looks as she has, nor have their girls become queen. She makes a deep, straight-backed curtsey to her daughter, then rises with an audible snap of knee-joints. The poet Skelton once compared her to a primrose. But now she is sixty.'

Additional: The orange coat is a like a thread stitching 1536 back to 1527… I was struck this week by how this chapter manages to be both joyful and fretful, layered with hope and melancholy, life and death.