📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 47 of Wolf Crawl

This week we are reading the second half of ‘Ascension Day, Spring–Summer 1539’ This runs from page 651 to 682 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “One morning after Easter he wakes with a heavy, aching head, his neck stiff.” It ends: “Five days. Wolf Hall.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

After Easter, he falls sick. It is the Italian fever and he leaves his chair at council vacant, for other men to fill. It’s a good day for Gardiner when Cromwell retires early to his bed.

Stuck at St James’s, he is burned in the forge, frozen in the ice. His memories pull him back through snow at Lewes Priory to the eel boy at Putney, the boy’s body sliced in the dark, while Walter sings at home.

Back in 1539, the fever recedes to reveal the damage done. He must act fast to secure the Cleves marriage. But Gardiner has been busy unpicking his work and six articles pass in Parliament, the king cleaving to the old religion. Hugh Latimer resigns and Cranmer sends his wife home.

He, Cromwell, no longer trusts Fitzwilliam and he no longer trusts Audley. He vows to bring Stephen Gardiner down. In boiling June, he talks with the new French ambassador, and at supper, Gardiner accuses him of murder. He, Lord Privy Seal, close to punches Uncle Norfolk.

Now he cannot hold the memories back. They distract him from his business, as he remembers the morning after he killed the eel boy, his own body bloodied on the cobbles. ‘One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.’

Parliament rises and the king begins his summer progress. Cromwell over plums, the fruits of success, marks out the itinerary. He recalls the day the king lost his hat while hunting, and all his party went bare and burnt-headed. ‘Mid-August,’ he writes. ‘Five days. Wolf Hall.’ He pictures Henry’s cap badge winking from above, seeing ‘us as we are now: girth thickened, sins multiplied.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • William Fitzwilliam • Thomas Audley • Stephen Gardiner • William Butts • Gregory • Henry VIII • Thomas Norfolk • Thomas Culpepper • Richard Cromwell • John Stokesley • Thomas Cranmer • Hugh Latimer • Charles de Marillac • Call-Me • Mathew

This week’s theme: ‘Eel boy, are you tired of life?’

Months, years have gone by, when Lord Cromwell has never thought of his early life; when he has pushed the past into the yard and barred the door on it.

The eel boy appeared first in the chapter ‘Wreckage (II)’ in a memory concealed within another memory. Cromwell recalled the day he stood over his sovereign as Henry murdered Francis Weston, with ink on paper. That memory compelled him to recall the day he ensured the eel boy was punished for something he, Cromwell, did.

Each stroke of the pen will translate into a stroke of the axe. Like the eel boy, they will understand that if Thomas Cromwell says, ‘You did it,’ you did it. No use arguing. It only prolongs the pain.

These are not memories he chooses to revisit. The next time the eel boy slips in, it is Spring, 1538, and he is thinking about how he has grown immune to insults. ‘Look at me,’ he thinks, ‘I take them as compliments. Norfolk calls me vile blood. The north calls me a heretic and a thief.’

The eel boy in Putney used to say to me, ‘Yah, Thomas Cromwell, you miserable gibbet-bait, you toss-brain, you remnant, you crumb: your mother died rather than look at you longer.’

This memory seems safe. It proves he has always risen above it, kept his face, and found a better way to be.

‘In reply he had said naught. He never said, ‘I’ll spit you, I'll stab you, I'll carve out your bloody beating heart.' Till, of course, he did.

He cuts the memory off before it has chance to take hold. But now it is Easter, 1539, and his Italian fever sends him back down to Putney.

Saturday night you chased him uphill.

The following section is addressed entirely in the second-person, to ‘you’, Thomas Craphead. His slippery pronouns have always kept us close. But now his memory is a monster, eyeballing us from the ceiling above our bed. We did this. I did this. You killed the eel boy.

You bend and pull out the knife. Something comes with it: a loop of his tripes. Your first thought is for the blade. You wipe it on your own jerkin, an efficient action, one-two.

Next day, he cleans it again then goes down to the brewery yard, unarmed.

Never underestimate Walter, his violence and cunning. The first blow came from nowhere and stunned him. There was blood in his eyes and after that Walter could do what he liked. He did it with his feet and he did it with his fists, till he, Thomas, was a bleeding jelly on the cobblestones, and his father stood over him and roared, 'So now get up!'

The first line of Wolf Hall. We have come full circle to the inciting incident of Cromwell’s story. Thirty-nine years ago he killed a boy in Putney and then his father almost killed him. ‘I’ve had enough of this,’ he thought, and hit the road. To Dover and the Three-Card Trick. Italy and Garigliano. The Frescobaldi and Scaramella’s off to war. Antwerp and Anselma. Liz, Anne, and Grace. The cardinal’s man: loyal dog when the house fell in.

Stephen Gardiner: ‘The lad you knifed in Putney died … You did well to run, Cromwell. His family had a noose for you. Your father bought them off.’

Fish face Stephen and the eel boy slip over each other in our mind. Cromwell remembers that, ‘The time he spends with his sister, it gets him out of Walter’s way, but then again it allows the eel boy to arm his band.’ While Crumb is in a fever, the king has ‘put a plaice’ in his seat. Gardiner is back. ‘He does not know how the feud began,’ but he knows how it will end.

Gardiner knows he is a murderer. But at Lambeth Palace, Stephen accuses him of poisoning Cardinal Bainbridge in Rome in 1514. It’s a feint, a ploy, to remind everyone sitting that Cromwell was Wolsey’s dog with a dark and murky past.

Now it is not Gardiner’s questions about Italy that trouble him: Italy keeps its secrets. It is Putney that works away at him, distant but close.

He once boasted of a prodigious memory. ‘The only things he cannot remember are the things he never knew.’ But the eel boy in the warehouse, the dogs at Smithfield, slink out of the shadows. Jenneke and Dorothea. They pull him down; the things he cannot forget.

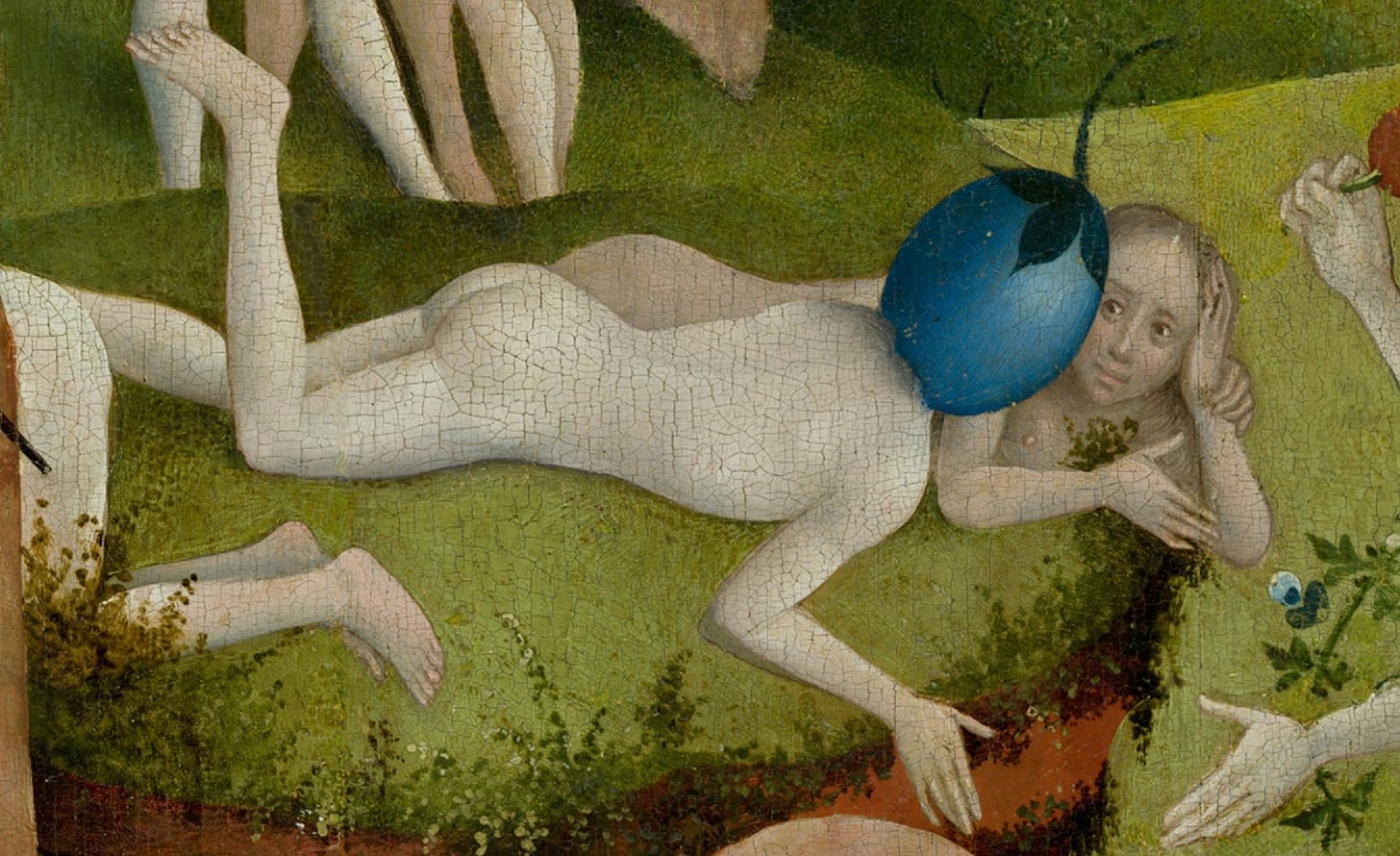

‘He dreams of a disembodied self walking in deep woods. There are mirrors set among the trees.’

Footnotes

1. Siege Perilous

His head is pounding. As the meeting rises, Audley says, 'Now don't be late again, my lord. We are the fellowship of the Round Table, you know, and that chair of yours is the Siege Perilous. It stood empty for ten thousand years, till Lord Cromwell came to fill it.'

This is the ‘perilous seat’ reserved by the wizard Merlin for the knight who will find the Holy Grail; to all else who sit on it, the chair proves fatal. In Thomas Malory's version of the tale, Galahad takes the seat and survives, proving him the most perfect knight. Galahad fulfils his destiny as the Grail Knight and ascends to heaven.

Thomas Audley has a bad habit of making jokes on grim occasions. William Fitzwilliam points out that they ‘dare not’ act without Cromwell. It is ambiguous whether this is because they fear Cromwell or Henry or both. I think both. We discover soon that Gardiner has taken up this perilous seat in Cromwell’s absence.

It is unclear, in this year, 1539, which of the two men the chair will destroy.

Further reading:

2. Abide awhile! Why have ye haste?

Back in ‘Broken on the Body’, the king is biding his time as his wife goes into labour:

In the evenings he tunes his lute and sings. He sends love tokens to his wife. Sometimes he talks about when he was young, about his brothers who have died. Then his spirits rally and he laughs and jokes like a good fellow among his friends. He sings a ditty Walter Cromwell used to sing: O peace, ye make me spill my ale … Where did he hear that? No women are assulted in the king's version, and the words are cleaner.

This is a version of the ballad Henry sings:

The night Cromwell kills the eel boy, his father starts up a bawdy version of the song: ‘By Cock, ye make me spill my ale.’ This violent song chases Cromwell as he stalks the eel boy to his uncle’s warehouse. They are still bellowing the tune when it is all over.

There is so much going on here. The ballad entwines low and high Tudor society: Cromwell has come so far but he’s barely left home. Putney is ‘distant but close.’ As Stephen Gardiner embodies the eel boy, the king is Walter. The father who sings out the night; then kills you for breakfast.

Further reading:

3. Axe have I

'Father, I am ready,' says Noah's son in the play. Axe have I, by this crown, as sharp as any in all this town. I have a hatchet, wonder keen, To bite well, as may be seen ... Then Noah and his sons make a ship. And sail forth, on God's tide.

Cromwell is thinking of ‘Noah’s Flood’, one of the cycle of Chester Mystery Plays, first performed in that town in the fifteenth century. The plays were performed at the Feast of Corpus Christi until they were outlawed during Queen Elizabeth’s reign. The Church of England regarded mystery plays as a form of popery and Chester was the last town to resist the ban, finally conceding in 1578.

The Chester plays were revived in the twentieth century at the 1951 Festival of Britain, and Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky both adapted ‘Noah’s Flood’ for opera.

The line Cromwell recalls is spoken by Noah’s loyal son, Shem. Together they build the ark and survive the flood; his axe and hatchet are used for good. But moments before, Cromwell pictures himself dragging his father out and felling him ‘in common view’ of the good folk of Putney, Mortlake and Wimbledon. A mystery play worth paying to see.

Walt’s rape song and gutting the eel boy. Man and boy, Cromwell hates his dad, but he is his father’s son. He cannot escape Walter Cromwell, no matter how far he runs.

Further reading:

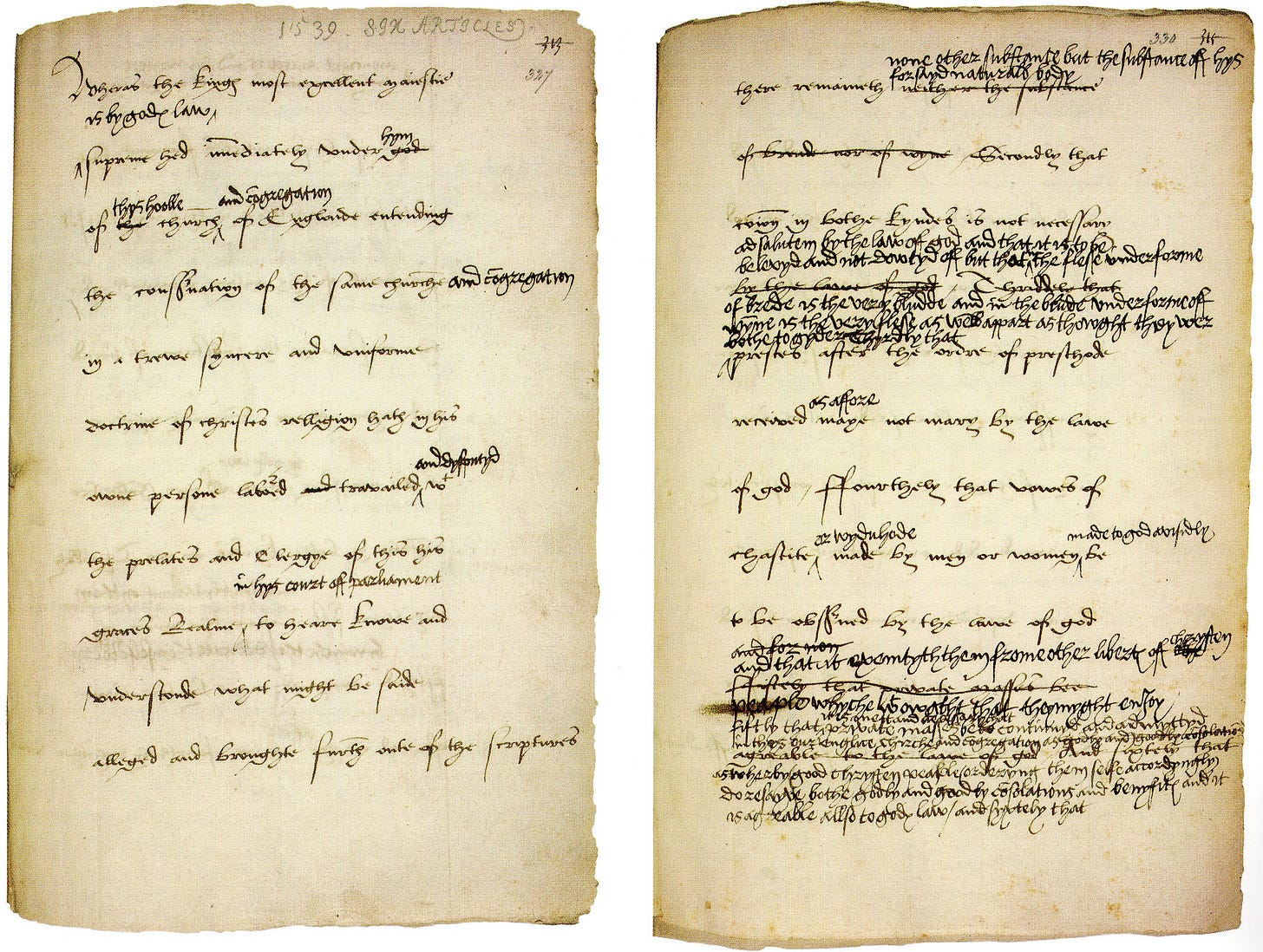

4. The Six Articles

There is no doubt, his sickness has set back the cause of the gospel – his brothers too afraid and too disunited, without him, to present a firm front.

In April 1539, Cromwell fell ill. Diarmaid MacCulloch writes that Cromwell’s description of his illness as ‘ague’ and ‘tertian fever’ suggests Lord Privy Seal had malaria. He later blamed his illness for allowing conservative bishops to take control of proceedings in Parliament.

The king had asked for religious unity. Reforming priests were saying mass in English and (like Cranmer) marrying without authorisation. In the wake of John Lambert’s execution, Thomas Audley drafted an act to reach a consensus on the eucharist – Corpus Christi. The matter was expanded to consider six articles of faith. A committee of eight bishops reached a settlement that sided with the conservatives on all but one: the divinity of confession.

The Act became law in June and the penalty was death, by burning or hanging. Hugh Latimer resigned and was imprisoned in the Tower. Parliament delayed the deadline for priests to put away their wives, giving Thomas Cranmer a period of grace to send his wife abroad.

To console his archbishop and reconcile the parties, Henry instructed Cranmer to hold a feast at Lambeth Palace for all members of the House of Lords. It was meant to bring everyone together. As we saw in this chapter, the result was the opposite.

5. Two comets and one death

From Italy come reports of two comets seen on one day. Suppose one comet stands for the end of the Empress: what else does He have up his sleeve, the creator of the moon and the stars?

On 22 May 1539, John Husee wrote to Lady Lisle: ‘These two days two comets have been seen the same day. Some said it was for the Empress and the son of the King of Portugal, others that it was for our Holy Father; one of the latter has been put in prison.’

The Empress was Isabella, wife to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. Despite long periods of separation managing their vast empire, Charles and Isabella had a mutual affection for one another. As Wyatt writes to Cromwell, the emperor retired to a monastery for two months. For the rest of his life, he wore mourning black and never remarried. Not so for our good king Henry.

6. Death of a cardinal

Any number of people would have employed Cremuello to watch Bainbridge’s back gate, and several did; he split the intelligence between them, with attention to what they wanted to hear.

As Cromwell correctly points out, he did not work for Wolsey when he was in Italy. Gardiner is rumour-mongering and he knows it. But Cremuello would have been happy to watch a gate for a fee. The ‘private business’ he refers to was a London legal case which brought him to Rome in 1514 where he made a lasting friendship with Bainbridge’s nephew, Lancelot Collins.

Diarmaid MacCulloch notes that the murderer Rinaldo de Modena was reputedly Bainbridge’s lover. Sex, money and power on a burning Italian night. The post-illness Cromwell slips into another reverie. He recalls the prostitute he met at Bainbridge’s gate. ‘How had one the energy, in that heat?’

7. St Hubert Squints

In Savernake, Hubert squints down, entangled in branches. In high summer we will ride the same paths and he will see us as we are now: girth thickened, sins multiplied.

Hubert of Liège was an eighth-century bishop and patron saint of hunters and knights. Hubert was converted by the vision of a crucifix between the antlers of a stag he was hunting. In 1444, the Duke of Jülich-Berg founded the Royal Order of Saint Hubert. That order is currently administered by Wilhelm of Cleves, the brother of a certain Anne of Cleves.

That is a tangent. This is a footnote: ‘When the wind takes off a gentleman’s hat, his companions at once take off theirs. The courteous man says, put on your hats again, do not suffer for my sake.’

Please remember that matter of protocol, as we enter our final weeks.

Quote of the Week: No defence against his memories

I leave you this week with this magnificent paragraph on the unravelling of Cromwell’s memory:

Months, years have gone by, when Lord Cromwell has never thought of his early life; when he has pushed the past into the yard and barred the door on it. Now it is not Gardiner's questions about Italy that trouble him: Italy keeps its secrets. It is Putney that works away at him, distant but close. When he was weak from fever the past broke in, and now he has no defence against his memories, they recapitulate themselves any time they like: when he sits in the council chamber, words fall about him in a drizzling haze, and he finds himself wrapped in the climate of his childhood. He is a monk who descends the night stair, still wrapped in dreams, so that the shuffling feet of his brethren are transformed to the whisper of leaves in the forests of infancy: and like a hidden creature stirring from a leaf-bed, his mind stirs and turns, on a restless circuit. He tries to tether it (to now, this time, this place) but it will roam: scenting the staleness of soiled straw and stagnant water, the hot grease of the smithy, horse sweat, leather, grass, yeast, tallow, honey, wet dog, spilled beer, the lanes and wharves of his childhood.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading ‘Twelfth Night, Autumn 1539’ This runs from page 683 to 718 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “In August Hans rolls up the bride, brings her home, and slaps her on a panel for the king’s inspection.” It ends: “The king will meet her at Blackheath, conduct her to Greenwich palace, and marry her by Twelfth Night.”

If you are enjoying this slow read, please consider recommending it to others so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. You can now give your friends, or your enemies, the gift of Cromwell with an annual subscription to Footnotes and Tangents.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Phenomenal chapter, phenomenal write up. The moment Walter says, "So now get up!" was a jolt. I read the trilogy the first time as the books were released and didn't see that Mantel had brought us full circle. This time I FELT it. And to realize the poor beaten child we first met in WH had just become a murderer, it's a lot to process.

I notice the way that the bawdy song is reflected in the dialog between eel boy and Cromwell. Mantel shows that those drinking songs contain real horror.

The pictures Mantel paints in this chapter are so vivid, I could not help but feel Cronwell's sickness and the heaviness he must have felt. The way Mantel ties books and stages of Cronwell's life together is genius. The way you let us see these connections in the story is done so well and I always look forward to these listen alongs, although I am getting more reluctant to come to the end!