📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 49 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the first half of ‘Magnificence, January–June 1540’ This runs from page 719 to 765 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “The king’s new castle at Deal is a way station for Anna to wash her hands…” It ends: “The loss of the boy is like a cold wind on his neck.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

Anna moves through the realm towards Cromwell and her king. He, Lord Privy Seal, sends her a welcome present: a gold chalice and fifty sovereigns. His sovereign, Henry, rips up protocol and sends himself, in disguise, upon the road to meet his bride. His chief councillor thinks it is a very bad idea.

It is his son, Gregory, who brings the news. Henry ambushed Anna at Rochester. She was warned, but she was not ready. First, she ignored him. And then she flinched. And nothing on Earth can roll back time and undo the damage done in that first glance.

He joins the king at Greenwich, where Henry is full with regret. He is looking for some way out. Next day, they are all at Blackheath to receive their new queen. The rain has abated, but here is Stephen Gardiner at our side, crowing at any sign of failure in Cromwell’s cause.

He breaks the bad news to the Germans: the king wants to delay. In the council chamber, there is talk of blame, and the king sees only dishonest men who have served him ill. ‘Walk with me,’ he tells Tom. Cromwell assures Henry that it can all be altered; all made right. The king shakes his head.

The Cleves delegation swears Anna is free to wed; she, herself, takes an oath. So, without further delay, they marry. Elaborate ceremonies keep the newlyweds from the conjugal bed: a new painting of the boy prince Edward, a play battle where Britain always wins. Master Sexton, as our Lord Privy Seal.

Next day, the news is bad. His king cannot do it, will not do it. And despite what Tom Culpepper says, he, Cromwell cannot do it for him. The doctors recommend abstinence. The council meet to discuss the disaster; an unseemly conversation ensues. He, Cromwell, insists this marriage is necessary for the good of England.

He visits his leopard with its murderous thoughts. He advises a show of affection to reassure England that all is well. He makes Fitz deliver the message to the king. Fitz and Henry reluctantly obey. Abroad, Wyatt works to prise apart the alliance between France and Spain.

He goes to Westminster Abbey to consider pendants and ladders. Edward Seymour is sent to Calais, and Rafe Sadler to Scotland.

The loss of the boy is like a cold wind on his neck.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Anne of Cleves • Charles Brandon • Richard Sampson • Thomas Cranmer • Duke of Norfolk • Henry VIII • Thomas Culpepper • Thomas Wriothesley • Gregory • Stephen Gardiner • Charles de Marillac • Bess Seymour • William Fitzwilliam • Bishop Tunstall • Thomas Audley • Christophe • William Kingston • Henry Bouchier • Katherine Howard • Jane Rochford • Master Sexton • Richard Riche • William Butts • Edward Seymour • Dick Purser • Mary Fitzroy • Thomas Wyatt • Rafe Sadler

This week’s theme: The Blame Game

'Blame himself?' Tunstall says. 'The king? When has that happened? You would think Cromwell had never met him.'

At Westminster Abbey, Cromwell looks up ‘at the fan vaulting of the new chapel.’ He is convinced the pendants are shifting, but the monks assure him otherwise. ‘It is only the building settling.’

The motif of a collapsing building runs through the trilogy. In Wolf Hall, Cromwell is Simonides, remembering ‘exactly where everyone was sitting, at the moment the roof fell in.’ The building was Wolsey’s world; and the people were those loyal to the cardinal, and those who destroyed him. In Bring up the Bodies, Cromwell invites the old families to a phantom supper in his mind’s eye. It’s an unholy and dangerous alliance against Anne Boleyn. ‘He glances up at the beams … Let us hope the roof doesn’t fall in.’

Now, he is standing in another great hall: England, 1540. If Henry VIII marries Anna, joins with Cleves and the Schmalkaldic League against Rome, we will be in a new world indeed. We will no longer have to choose between France and Spain, and perhaps the balance of power in Europe may shift north and towards a reformed church under a constellation of enlightened princes.

That’s the plan, anyway. But look up. Is that this brave new world settling into its foundations? Or have the pillars and pendants shifted? Is a fatal flaw in the architecture about to bring everything crashing down?

‘He wants to walk away: for his own protection.’ If the building collapses, you don’t want to be inside, alone with the king, ‘as in a wasteland.’

Henry says, ‘you cannot be blamed.’ Suffolk, Audley, Cranmer stand by the marriage. ‘He agreed to it,’ says Brandon. ‘He signed up. He cannot jib now.’ Hans cannot be blamed. Fitz will not be blamed. So who is at fault? And to quote Thomas Wyatt, ‘What means this?’

'It is his own fault, if fault there is. For rushing about the countryside like a love-lorn youth.'

He, Cromwell, picked his prince. He wrote The Book Called Henry. But too often these days, he finds himself thinking he could do a much better job himself. He thought so when Jane died. And he has got into the dangerous habit of saying these things out loud. No wonder, men are mocking him in earshot:

‘If the king cannot manage it with the new queen, Cromwell will do it for him. Why not? He does everything else.’

But he is not the man he was. He is ‘a man with a past’ who is undone; he does not know everything and, ‘He says to himself, I cannot think of everything. He hears the king’s voice saying, why not?’

Instead, he lies in bed, the storm raging about his house. He does not feel invincible tonight. He ‘should have a grand plan’ but is now ‘pushing through, hour to hour.’ He boasts to Stephen Gardiner that he cleared the skies for Anna at Blackheath. ‘I sold my soul,’ he says. It is the kind of thing Wolsey used to say, before the roof fell in.

But he is not the weather maker; the weather is unmaking him. ‘Losing, losing, all the time.’ It takes a doctor, William Butts, to tell it how it is:

'All men do sometimes fail,' Butts says. 'You need not look as though that is news to you, Lord Cromwell.'

Footnotes

1. Fortified England

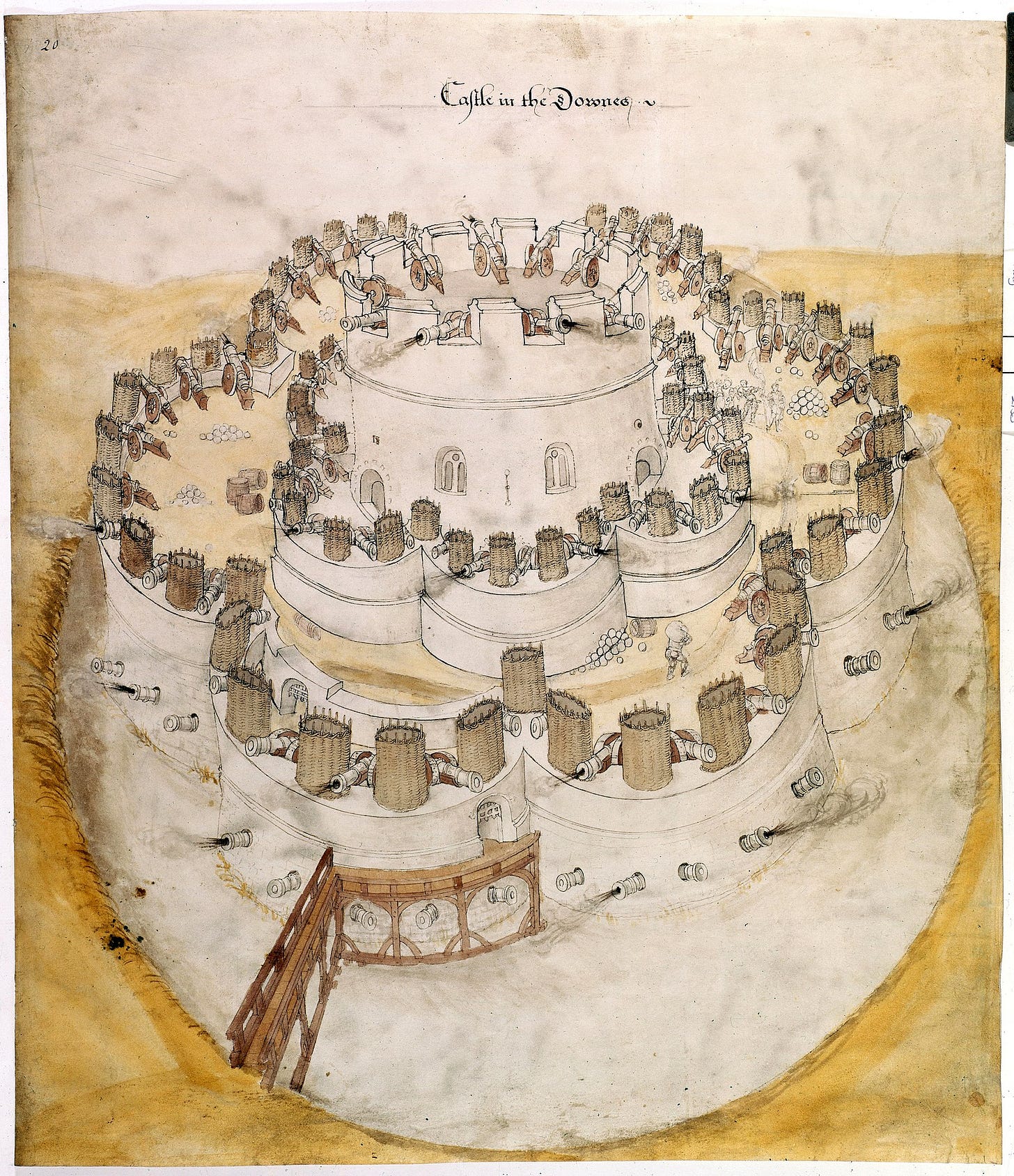

The king’s new castle at Deal is a way station for Anna to wash her hands, take a fortifying glass of wine, and then pass on to Dover.

The wine fortifies the bride, who wore her clothes like armour in the picture Hans painted. Cromwell has already alluded to the programme of fortifications that have turned England into a castle island. These were Henry VIII’s Device Forts, built to repel a joint invasion from France and the Empire. The programme cost £376,000, estimated at anywhere between £2 billion and £82 billion in modern money.

The Device Forts were financed by the dissolution of the monasteries, but were never needed during Henry’s reign. After a raid on the Isle of Wight in 1545, England faced no further invasion until the Spanish Armada in 1588, by which time many of the forts had been decommissioned, and the defences were out of date.

Further resources:

2. Little bundles of time

It is Rolewinck's history, where all the dates before Christ are printed upside down. Jane Rochford's father sent it, and he can never just leave you to read; he writes Mirabilia! beside events he particularly enjoys.

Lady Rochford’s father is Lord Morley, a scholar and translator. His reading material keeps finding its way to Cromwell’s desk: his daughter brought him Machiavelli’s book in an earlier chapter. Later in this week’s reading, Morley and Gregory are discussing the veracity of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of Britain.

Cromwell is currently thumbing a book by a Carthusian monk called Werner Rolevinck. It has the fabulous title, Fasciculus temporum or ‘Little bundles of time’. One of the pages he turns to has a picture of the Tower of Babel, the biblical building designed to reach high up to heaven. God punished men for their pride by confusing their languages so they could not work together.

This week, we are surrounded by references to time. Werner’s ‘little bundles of time’ is one version of history, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s is another. Cromwell suspects the chroniclers of ‘snipping sections out of history’ to make Henry VIII the one-hundredth king. Gregory thinks Geoffrey was ‘such a liar’ who probably never went to Monmouth.

Cromwell is ‘a man with a past’ but no future. He considers Lord Morley’s book and says: ‘We must roll back time.’ But it cannot be done. The Duke of Saxony sends a clock that you can hold in the palm of your hand. It is a modern mechanical marvel, but it does not excite the king:

'Thank you, my Lord Cromwell, you always have something new. Though sometimes not as new as one would wish.'

Yesterday’s man, all out of surprises and with nothing new to offer his king.

Further resources:

3. ‘A love-lorn youth’

In his imagined hall at Rochester, the light is failing. Below the queen's window, soundless, the bull-baiters roar. The dogs hang from the bull's flesh. Slow gouts of blood patter onto the paving.

Cromwell is not present for one of the most consequential meetings of his life. He has to picture it. We have accounts from the chronicler Edward Hall, the herald Charles Wriothesley, and the Master of the Horse, Sir Anthony Browne. It is Wriothesley’s version that mentions the bull-baiting.

‘It is what a king does,’ Henry tells him. ‘You cannot know, Cromwell, you are not a courtier born.’

Cromwell, the commoner, has been wrestling all this time with lords who insist on playing chivalric games in an era of Realpolitik. Gregory tells him he should have prevented it, and I wonder whether the 1534, 1535 Cromwell would have found a way, where Cromwell circa 1540 could not?

According to chivalric tradition, Anna should penetrate Henry’s disguise to recognise her true love. Caught off-guard in a strange land, she sees an old, overweight man in a marble cloak. She flinches. Gregory says, ‘Any man would have been stricken.’ But it is not Henry’s wounded pride that I think about most: it is the torrent of emotions Anna must have felt, and the way she picked herself up and carried on.

She is lovely in the shadows, then. And when facing front. He could almost laugh.

The king alone thought her unattractive. As Cromwell confirms later, ‘there is nothing to offend.’ This creates consternation amongst his councillors. There is nothing wrong with her, ‘except his dislike.’ Ordinarily, this would not be a problem: sixteenth-century princes did not marry for love. The problem is Henry, who wants to love and be loved.

And if he can’t be either of those things, then someone must be to blame.

Gregory says Anna took Henry for a ‘Jolly Jenkin’. This is a reference to a popular medieval carol where a lascivious cleric flirts with a maidan while performing mass. Alison extolls Jolly Jenkin’s art of seduction, but it is clear she is mocking him, as he winks and steps on her foot.

Henry says Anna looks like ‘the Cornhill Maypole.’ A maypole is a tall wooden pole raised during festivities on 1 May. London’s maypole was kept at St Andrew Cornhill, later St Andrew Undershaft. In 1517, it was attacked during the Evil May Day riots, an outburst of anti-immigrant violence when Henry was still a young king.

Further resources:

4. What Means This?

Three times he rises and opens the shutter. There is nothing to see but a muffled, starless black. But the drumbeat of rain falters, dawn stripes the sky in shades of ochre, and the sun feels its way out of banks of clouds.

How is it that we can always remember what the weather was like the day our lives fell apart? I love this long lonely night of Cromwell’s, listening to the wind and rain, Wyatt’s words in his head:

What means this when I lie alone?

I toss, I turn, I sigh, I groan.

My bed to me seems hard as stone

What means this?

Wyatt is, of course, writing about love. In another verse, he writes of sitting beside the woman he loves, ‘With loud voice my heart doth cry / And yet my mouth is dumb and dry.’ Like Cromwell, Wyatt is alone and lost for words. Meaning has bled from the world: ‘What means this?’

Cromwell does what we all do: He takes a work of art – a poem, a song, a novel – and transposes it into the language of his own heart.

Further resources:

6. Blackheath

By nine o’clock, when he is at Blackheath on horseback, there is a white haze over the fields: in that haze, the freefolk of England.

Blackheath is a wide expanse of open ground southeast of London. Many believed it earned its name as a mass burial ground for victims of the Black Death, but more plausibly, its name comes from the Old English for ‘dark soil.’ It is a bleak place to begin our last year on Earth.

Wat Tyler’s rebels rallied here in 1381. Jack Cade’s revolt camped here in 1450 before marching on London. And in Cromwell’s lifetime, the Cornish rebels were slain at the Battle of Blackheath in 1497. Henry IV met the Byzantine emperor on these fields, and London welcomed a triumphant Henry V back from the Battle of Agincourt.

There is too much history in these fields.

Further resources:

Quote of the Week: Stairway to Heaven

What did Francis Bryan say to Cromwell? ‘You climb so fast, my lord, the kingdom has not ladders enough.’ As a boy in Putney he was always up ladders, looking for a better view.

I love this quote about the Stairway to Heaven, especially the line: ‘easy to climb. Harder to know what to do when you get to the top.’ That question has dogged Cromwell since 1536: What is he for? Where is he going? He can almost touch the angels now, but what for? What means this?

There is an indulgence granted to those who attend a Mass here, which all of us will need one day: it is called the Stairway to Heaven. St Bernard in a vision saw souls ascending, rung by rung into eternity; angels give them a hand to balance, as they hop off the last rung into bliss. It is easy to climb. Harder to know what to do when you get to the top. As we labour upwards, the Fiend shakes the foot; and treads can snap, or the whole structure sink in boggy ground. He says to Riche, 'Ricardo, do you think there is a flaw in the nature of ladders, or a flaw in the nature of climbers?' But it is not the sort of question to which the Master of Augmentations likes to apply his mind.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the second half of ‘Magnificence, January–June 1540’ This runs from page 765 to 806 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “When the court moves to Westminster, they go by river.” It ends: “The flint sparkles like sunlight on the sea.”

If you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These donations always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

And if you are enjoying this slow read, please consider recommending it to others so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. You can now give your friends, or your enemies, the gift of Cromwell with an annual subscription to Footnotes and Tangents.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

I'm happy to have caught up again, having fallen disastrously behind. (House-moving and travelling are all very well, but they get in the way of the really important things in life: BOOKS.) In an effort to get back in the game, I've been listening quite intensely over the last couple of weeks, and I'm now definitely at the point where I can hardly bear to continue (but will, obviously...). Such darkness. So many burnings. So many horrible memories creeping out of Cromwell's past. Such a ridiculous king... Thanks, Simon, for your expert guidance (your "eel boy" exposition a couple of weeks ago was particularly memorable). I'm in now till the bitter end (albeit hiding behind the sofa).

The disguise bit when Henry surprises Anne of Cleeves is one of my favorite parts of the whole trilogy. What a delicious disaster!