📖 This is a long post and is best viewed online here.

👆 To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for 2024 Wolf Crawl.

🎧 This post is now available as a podcast. Listen on Spotify, YouTube, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Week 48 of Wolf Crawl

This week we are reading ‘Twelfth Night, Autumn 1539’ This runs from page 683 to 718 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “In August Hans rolls up the bride, brings her home, and slaps her on a panel for the king’s inspection.” It ends: “The king will meet her at Blackheath, conduct her to Greenwich palace, and marry her by Twelfth Night.”

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Give someone the gift of Cromwell in 2025

Wolf Crawl will run again next year for paid subscribers. All my posts will be revised and updated so that more readers can savour these extraordinary books in a slow year-long read. If you know someone who would enjoy this experience, consider a gift subscription so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. Paid subscribers can also join the War and Peace readalong, read any of my book guides, or take part in any of the other 2025 slow reads.

Last week’s post:

This week’s story

August, 1539. Hans brings him Anna of Cleves. The king is pleased with the painting of his bride-to-be, and copies are made. Edward Seymour and Charles Brandon give their full-throated support. Norfolk grunts.

He, Cromwell, must reassure his monarch. Anna has no English or French, does not sing or dance, play music or hunt. Worse still, she is not the Duchess of Milan. Norfolk suggests sending Surrey to seal the deal. Keep the Howards in command. Cromwell thinks, keep them out in the cold. The deal is done.

He must prepare Margaret Pole for a long incarceration at the Tower. He must assuage brother Cranmer, doubting Thomas. We must press on. Bishop Gardiner calls us heretics at council, causes a ruckus and is thrown out. Bishop Stokesley is dead. Clear skies at last?

At Leeds Castle, he gives Gregory his instructions. His son is to Calais to offer the Cromwell hand of friendship to the incoming queen. He, Gregory, tells his father how he feared him as a child. ‘You were too busy to strike me.’

Stephen Gardiner is interrogating evangelicals off the boat, hunting for a trail back to you. Your nephew digs up ancient lovers from the earth, then puts their bones back beneath his house. ‘I can live with them under my floor,’ he says. The German delegation arrives, and in October, at Hampton Court, the marriage is made.

All we lack for now is the queen herself. This winter, the last of the abbeys come down. The saints swept out. Anna will find a new England, ‘repainted, re-enamelled, bleached, scrubbed clean.’ Edmund Bonner bounces back to England to be Bishop of London, the English Bible in his hand.

Lady Rochford heads the new queen’s privy chamber. With her come a blizzard of Howard women and memories of Calais, Lady Carey and a knife to the throat. The day Gregory leaves, a leopard is brought to Austin Friars in a cage. It stares at him, with an expression of ‘awe, or fear, or rage.’

You turn your attention to Lady Mary’s marriage prospects; her suitor, the Duke of Bavaria, comes to fetch his bride. The year closes with you and Henry remembering the past, for we have so much of it. The king says he thinks you blame him for Wolsey’s death. And there’s nothing you can say to that.

Now, 1540 has arrived. And with it, Anna, on the road to London from the east. Our morning star to Greenwich Palace. She will marry England by Twelfth Night. And then, God willing, all will be well.

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Hans Holbein • Henry VIII • Edward Seymour • Charles Brandon • Duke of Norfolk • William Fitzwilliam • Margaret Pole • Thomas Cranmer • Stephen Gardiner • Thomas Audley • Call-Me • Gregory • Richard Cromwell • Charles de Marillac • Thurston • John Stokesley • Edmund Bonner • Lady Rochford • Katherine Howard • Dick Purser • Lady Mary • Rafe Sadler • Cuthbert Tunstall

This week’s theme: The Bean King

‘I am greatly altered these ten years. You, not so much. You do not surprise me as once you did. I do not think you will surprise me again, considering all that you have said and done – some of it miraculuous, Tom, I will not deny.’

This is the second time that a chapter has withheld its title within the text until the last line. The first instance was Nonsuch, Henry VIII’s fairy tale palace, which he built while hunting for a new wife. Like The Image of the King, it refers to something that was conspicuously impressive but also impermanent: the palace and the painting were destroyed.

Twelfth Night marks the Epiphany, the arrival of the three Magi bearing gifts to Christ at Bethlehem. Anna of Cleves is making her own journey from the east to arrive on Twelfth Night at Greenwich Palace. Our future depends on this epiphany and this night: Thomas Cromwell has twice helped Henry between wives; can he accomplish the three-card trick one more time?

History knows the answer. According to tradition, on Twelfth Night, a bean and a pea are hidden in a cake. He who finds the bean becomes king for a night. She, with a pea in her slice, will be queen. The Bean King and Pea Queen will appoint their court officials and don their paper crowns. But come morning, they will be king and queen no more.

Anna is the Pea Queen: the marriage will last a matter of months. And he, Cromwell, is the Bean King. Henry reminds him, ‘You have few friends’. Everything he is, all he has, comes from the king. ‘If the light moves he is gone.’

With his enemies on the run, Stokesley dead and Gardiner off the council, Cromwell goes to see his son at Leeds Castle in Kent. He hopes for ‘clear skies’ but there are ‘scudding clouds’ above, ‘reflected in the blue, the whole world fluid and flickering.’ Anyone familiar with English weather will recognise this scene: a blustery wind blowing clouds between us and the sun; so that the strength of light and its warmth comes and goes: strong then weak.

He gives his son instructions for Calais. Surely, it is his apotheosis, his moment of magnificence: his son conveying a future queen of England to her king. But Gregory twists on the hook and tells his father that he was afraid of him as a child. ‘You were too busy to strike me.’ Once again, someone else’s memory contradicts our own. Perhaps we were not the ‘tender father’ we thought we were. Perhaps the fear we felt of Walter was communicated through our own force of will into the heart of our son?

Remember the Damascene cat and Cromwell’s seven lives? He must be on his eighth or last life now. To emphasise the fact, two cats cross our path. Thurston has seen the cardinal’s kitten Marlinspike, remarkably still alive after all these years. He’s ‘torn up a bit … But aren’t we all?’ Then a leopard is brought to Austin Friars: ‘Such a distance it has come, perhaps from China: how can it be still alive?’

He tells Wiliam Fitzwilliam about it, who relates a chilling tale of a seal he had made into pies. Diarmaid MacCulloch tells us that this Autumn, 1539, Fitzwilliam and William Kingston (Constable of the Tower) plotted to bring Cromwell down. They took their plan to Cuthbert Tunstall, who refused to join the party. He remained loyal to Cromwell, and here in this chapter, he wishes our Lord Privy Seal good fortune:

‘I am in my sixty-sixth year. Age has some advantages. As you will learn, my lord, if I pray God grants you long life.’

Footnotes

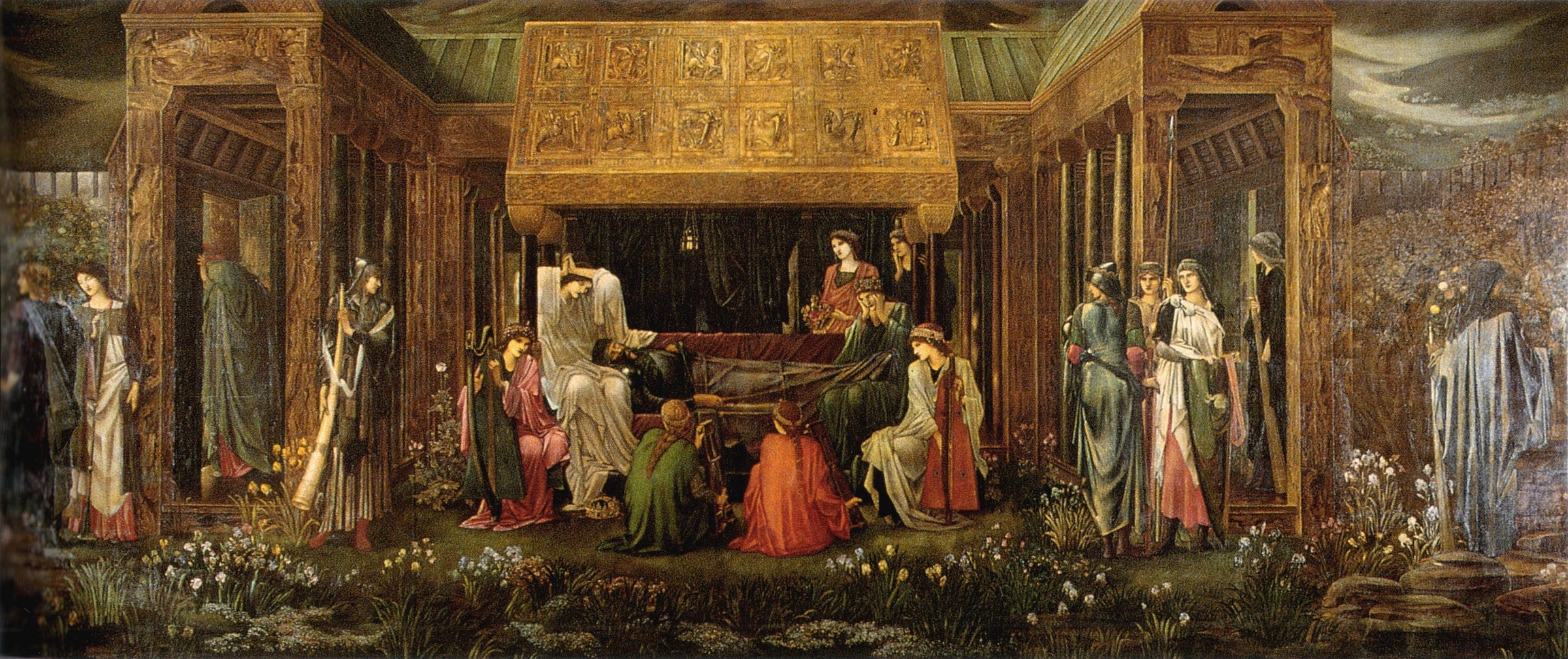

1. Anna’s Portrait

He steps back to admire her, a shining princess who is more metal than flesh. Her clothes mould her, like the armour of some goddess, and look as if they would stand up by themselves.

And so we get our first look at Henry VIII’s fourth wife. Holbein’s portrait is enormously consequential. In all Cromwell’s conversations with Holbein, there has been this tension between the artist and the politician. The German master believes in capturing face and character faithfully without flattery. Cromwell says, fine, but don’t push it. The king marries a painting of Anna and is less enamoured with her in the flesh. And the man who must deal with the difference is not Hans Holbein; it is Cromwell.

Anna’s portrait hangs in the Louvre. This year, it was beautifully restored, the queen emerging resplendent from the dark shadows. The detail and the colours are mesmerising. Anna looks like she may, any minute, lift her gaze and look straight at you. And perhaps for a moment, you feel you are Hans admiring your work: ‘Henry should like her … I would. You would. It is a good picture.’

A picture so good, it can kill.

Further resources:

2. The Knight of the Swan

The Duke of Suffolk gives his voice in council … do they not travel down the Rhine in boats drawn by silver swans? He, Cromwell, smiles. 'Perhaps in former times, my lord Suffolk.'

Charles Brandon is probably thinking of the Swan Knight, a medieval tale in which a knight comes on a swan-drawn boat to rescue a maiden in distress. If the maiden asks him his name, he will turn and sail home, never to return. In the Arthurian version of the story, he is Lohengrin, son of Percival, one of the knights of the Round Table. In 1848, Wagner based his opera Lohengrin on this legend.

In some tellings, the knight rescues the maiden. In others, she asks his name and is abandoned. We don’t know which version Brandon preferred, but we are sailing with our swans down the Rhine, hoping against hope for a happy ending. The tale rests on the danger of revealing one’s true identity: whether it be Cromwell’s conspicuously base beginnings or the living Anna behind the painting.

3. The Hinchingbrooke Dead

Two sets of bones: as Richard thinks, but they are not two nuns, as you might expect: one of them has a huge jawbone and giant-killer’s shoulders. Already the builders are making up stories about them.

In 1538, Richard Cromwell, alias Williams, son of Morgan Williams (brewer), bought the dissolved nunnery at Hinchingbrooke in Cambridgeshire. His son, Henry, enlarged the house which eventually transferred to the Montagu family. The royalist Montagus sent Henry’s grandson Oliver Cromwell to Parliament on their behalf in 1628. In 1649, Cromwell signed Charles I’s death warrant. In 1653, he became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth.

In 1834, builders came across two skeletons in stone coffins under the Grand Staircase at Hinchingbrooke House. For many years, these were believed to be the remains of two Benedictine nuns. However, more recent research revealed that one of the skeletons belonged to a tall male from the late 10th or early 11th century. The condition of their bones and burial suggest they were high-status:

Already the builders are making up stories about them. They are a runaway lord and lady, absconding for love of each other, whose flight has been arrested by a jealous count, or earl, or petty king. Standing hand in hand, they have been slain by their pursuers.

The story summons up a haunting image of a vengeful king hunting down his lord at the dawn of England, decades before William sailed the Narrow Sea and conquered it all. William I’s successor, Henry VIII, turns to his Lord Privy Seal and says, ‘Give me some credit, my lord. I am not a barbarian.’

Hinchingbrooke House is now a school. Since the 1960s, there have been many reports of ghostly apparitions, nuns at night, especially at the rear of the property where the old priory once stood; and at the Grand Staircase, where he, Cromwell, and his nephew Richard, now stand.

'And so?' 'So I put them back where I found them,' Richard says. 'I can live with them under my floor, they are not likely to get up and walk about at night.'

Further resources:

4. Marriage by proxy

That is what the French are like, the Germans say. A coarse nation, always pushing for things to be done their way.

In Early Modern Europe, dynastic alliances were frequently sealed by proxy marriages, against the day when the bride would be old enough and in a position to make the long journey to their new realm. Henry’s brother Arthur married Catherine by proxy, and his sister Margaret married James IV of Scotland by proxy at Richmond before travelling north.

These proxy marriages were often strengthened by symbolically consummating the marriage. The Germans are perhaps being disingenuous here. Charles V’s grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, married twice in this manner, his wives ritually lying down with his proxies.

The English endured this ‘coarse’ custom one more time in 1625, when Charles I made the controversial decision to marry by proxy the Catholic princess Henrietta Maria. Claude, Duke of Chevreuse, stood in Charles’s place at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris before spending a night side-by-side with Henrietta Maria to symbolically consummate the marriage.

Mary Tudor’s marriage did not last long; the French king Louis XII died the following year. Mary went on to marry a certain Charles Brandon, without her brother’s permission; they remained wed until her death in 1533.

Further resources

5. Christ in Albion, Arthur in Avalon and the end of the old magic

Adieu, Odilia, Aiden and Alphege, Wenta, Walburga, and Cesarius the martyr: sink from man’s sight, with your muddles and your mistranscriptions, with the shaking of your flaky fingerbones and the compound jumble of your skulls.

Cromwell wants a new England, free of myth and monks on the take. The gospel is a good enough story for Tom and his brothers. Good, because it is true. Cromwell, the iconoclast, lays waste to the Anglo-Saxon saints and the stories that go with them. What he sees are lies and confusion, superstition and extortion.

This is the beginning of what is sometimes described as the ‘disenchantment’ of the modern world. The argument runs that Europeans were a muddle of pagans and folk Christian mystics until the Reformation prioritised education, literacy and a popular understanding of Christian doctrine.

The problem, of course, is that stories are powerfully enduring. The old magic has deep roots, and men will not easily give up myth and metaphor:

No ruler is exempt from death except King Arthur. Some say he is only sleeping, and will rise in an hour of peril: if, say, the Emperor sends troops.

This is one version of a legend that is found all around the world: the king who sleeps in the mountain; the folk hero who will return when we need them most. Other sleepers include King David, Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. I have recently been reading The Weirdstone of Brisingamen trilogy written by British folklorist and writer Alan Garner, which explores a version of this myth in the Cheshire village of Alderley Edge.

Garner writes that myth is metaphor; we must tell stories because they give words to thoughts and feelings that have no words: yearnings, fears, imaginings, hauntings, miseries and ecstasies that, without myth, may scuttle away to shadow and dark.

Some say Jesus Himself trod this ground, a bruit that the townsfolk encourage: at St George’s Inn they have an imprint of Christ’s foot, and for a fee you can trace around it and take the paper home.

The legend is that Christ came to England with Joseph of Arimathea, who also brought the Holy Grail to the Vale of Avalon. What concerns Cromwell is that it is untrue, and is part of a spider’s web of fraudulent claims made by the unreformed church. The poet William Blake later incorporated this legend into his poem:

And did those feet in ancient time, Walk upon England's mountains green: And was the holy Lamb of God, On England's pleasant pastures seen!

Where Cromwell sees a lie, Blake extracts a metaphor, a symbol, a question:

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

The literal truth is less important than the yearning it conveys through metaphor: a thread tied between our familiar sense of home, an expression of the eternal and the perfect, and an exhortation to create an ideal society, ‘Jerusalem / In England’s green and pleasant Land.’ Adapted for music in 1916 by Hubert Parry, ‘Jerusalem’ has since become the unofficial national anthem of England.

Further resources:

Tangent: Alan Garner: The magical master of British literature

Tangent: Jerusalem — how William Blake’s poem became an anthem for all causes

6. Mary and Philip

The Duke of Bavaria has come into the realm, with a modest entourage as the king advised: unmarried, a very proper man.

I have run out of time this week, but a few small points relating to Lady Mary’s current marriage prospects. Remember that Emperor Charles V was manoeuvring to match Mary to Dom Luis of Portugal and that Cromwell stuck his oar in and made sure nothing came of it. Philip of Bavaria is a better pick for Cromwell's strategy of forming alliances with German Protestant princes.

Mary and Philip met and, despite their religious differences, appeared to like one another. Nevertheless, this match was overruled by her father, and the plan was abandoned. Mary would go on to marry another Philip, the emperor’s son and successor, Philip II of Spain.

She smooths her hands down her skirt, and hums a little. When sparrows build churches upon a green hill...

The tune is a warning, although I don’t think Call-Me and Cromwell can hear it. It is a fifteenth-century carol with the simple message that one should never trust women. A manuscript in the archives of Balliol College, Oxford, reproduces the line Mantel quotes as follows:

When sparrows build churches on a height

And wrens carry sacks unto the mill

On one of the seats at St George’s Chapel at Windsor, there is a carved image of sparrows carrying sacks on their backs into a windmill. The oak was carved during Edward IV’s reign, and Mary would have known the words well:

When these things following be done to our intent,

Then put women in trust and confident…

Here with Cromwell, Mary has coopted this misogynistic carol and given it a coded message: Do not trust me, Crumb. Perhaps Cromwell does get the drift, because he tells Mary not to play false, ‘say yes, yes, yes, and then at the last minute you say no. Because what would leave the king embarrassed.’

And there is nothing more dangerous than a king who feels a fool.

Further resources:

Footnote: ‘When to trust women’

Footnote: The carol in the archive and the chapel

Quote of the Week: You can write on England

My quote of the week is essentially a reprise of another great passage we encountered in week 15, Supremacy: ‘Beyond and beneath this whole realm of England … there is a buried empire.’ Back in 1534, Cromwell considered the impossibility of forcing the dead to swear allegiance to the king as head of the church and to his new marriage. Now, he wonders whether his iconoclasm will be enough to remake England:

Can you make a new England? You can write a new story. You can write new texts and destroy the old ones, set the torn leaves of Duns Scotus sailing about the quadrangles, and place the gospels in every church. You can write on England, but what was written before keeps showing through, inscribed on the rocks and carried on floodwater, surfacing from deep cold wells. It's not just the saints and martyrs who claim the country, it's those who came before them: the dwarves dug into ditches, the sprites who sing in the breeze, the demons bricked into culverts and buried under bridges; the bones under your floor. You cannot tax them or count them. They have lasted ten thousand years and ten thousand years before that. They are not easily dispossessed by farmers with fresh leases and law clerks who adduce proof of title. They bubble out of the ground, wear away the shoreline, sow weeds among the crops and erode the workings of mines.

Note the reference to Richard Cromwell’s ‘bones under your floor’ at Hinchingbrooke House. This theme runs through the trilogy: the dead hand of history, England’s buried empire of lives and stories gone before. Reformers like Cromwell, or revolutionaries like his descendent Oliver, will always try to build a new society – but these projects will be frustrated, complicated, obstructed, and undone by England’s entanglement with who and what it once was.

Of course, this now also has a personal inflexion. Thomas Cromwell has re-made himself as ‘Lord Cromwell, Lord Cromwell of Wimbledon, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal.’ But when a leopard comes to call, it sees only Tom from Putney and it is thinking ‘how to skin him from his furs, with one scalping flick of its paw.’ His memories, too, like uncaged beasts, roam wild in his mind and remind him that he is still the boy he was: beaten, a bully, and afraid.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we are reading the first half of ‘Magnificence, January–June 1540’ This runs from page 719 to 765 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: “The king’s new castle at Deal is a way station for Anna to wash her hands…” It ends: “The loss of the boy is like a cold wind on his neck.”

If you are enjoying this slow read, please consider recommending it to others so they can take part in Wolf Crawl 2025. You can now give your friends, or your enemies, the gift of Cromwell with an annual subscription to Footnotes and Tangents.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

Footnote: there are lots of indications in this chapter that Cromwell is losing his grip and is not as sharp as he once was. As one point he defends the church reforms with an anti-papal sound bite. He thinks, I suppose I could be more original. But I'm stuck on repeat. As Henry says, you don't surprise me anymore.

There's so much here! I love your play on words with doubting Thomas, referring either to Cromwell or Cramner.

In a lot of ways, the conversation between Henry and Cromwell about Wolsey feels like the climax in their relationship. It lays bare what has been happening between them. The first real moment I felt fear for Cromwell is when Henry consulted Norfolk (?) and Cromwell was surprised to learn that Henry witheld information from him. Cromwell definitely values power but I also think he values loyalty, while Henry only prizes what makes him feel good.

Cromwell is getting so swept in his past that Call-Me calls him out on it, and he forgets to mention Chapuys to Mary. Reading this last book makes me feel so apprehensive. I've become so attached to Cromwell that it's harrowing to get closer to the end.

There's so much light in this chapter. A poignant quote: "If God glanced down now, what would he see? Two ageing men in failing light, talking about their past because they have so much of it."