This is a long post and is best viewed online here. To get these updates in your inbox, subscribe to Footnotes and Tangents and turn on notifications for Wolf Crawl 2024. This post is now available to download as a podcast: search for Wolf Crawl wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to week 32 of Wolf Crawl

This week, we are reading the second section of ‘Salvage, London, Summer 1536’ This runs from pages 77 to 116 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘In his room at the Tower, Thomas Wyatt is sitting at the table where he left him…’ It ends: ‘…his burdened and oppressed flesh the place where all arguments come to rest.’

You will find everything you need for this read-along on the main Cromwell trilogy page of my website, including:

Weekly updates, like this one

Online resources about Mantel’s writing and Thomas Cromwell

Writing footnotes and tangents is a full-time job, so I am enormously grateful to paying subscribers who allow me to offer this book guide for free in 2024. As a paid supporter, you can read the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area. Alternatively, you can leave a tip to keep me fully caffeinated as I write. Thank you so much for all your support!

This is a long post and may get clipped by your email provider. It is best viewed online here.

Last week’s posts:

This week’s story

In the Tower, Thomas Wyatt is reading Petrarch. He wants to be free and put on the road, but the mood at court is still carnivorous, and he, Cromwell, wants Wyatt to live. Wyatt says he is in love with Bess Darrell, Katherine’s former maid of honour, and she is carrying his child.

At St James’s palace, the king’s bastard, Henry Fitzroy, is ailing. They are removing all memory of Anne from the architecture; not fast enough for the Duke of Richmond. ‘With every breath he commits treason’: he imagines his father’s death and himself as king. These are the fantasies of his friend, the Earl of Surrey, Norfolk’s headstrong son.

Rafe and Call-Me return from their interview with Lady Mary. ‘Never send me there again,’ Wriothesley pleads. He looks like he has been mauled by a lioness.

Parliament convenes at Westminster. Richard Riche honours the king with biblical allusions, and he, Lord Cromwell, Vicegerent in Spirituals, sits above the bishops in convocation. The bishops are in a reforming mood, while he, Baron Wimbledon, has his eyes on the manor houses of the archbishop.

He glides past a brace of Howards into the royal presence. A book has come out of Italy, from the king’s cousin, Reginald Pole. ‘Three hundred leaves, each leaf veined with treason.’ Henry believes the plot is to marry Pole to his daughter Mary and lead England back to Rome.

Now, it is clear why Cromwell did not fear his debt to the old families. The king sends him to question Reginald’s kin, where he explains that he is all that stands between them and Henry’s displeasure. At council, the king talks of bringing his daughter to trial, and Crum throws Fitz out the door for raising an objection.

The king tells him to ‘bring this matter to a conclusion.’ But what does he mean?

‘I think,’ says Edward Seymour, ‘he wants you to kill her.’

This week’s characters

Click on each link for more details and plot summaries for each character:

Thomas Cromwell • Thomas Wyatt - Martin - Gregory • Richard Riche - Christophe • Henry Fitzroy • Francis Bryan • Rafe Sadler • Thomas Wriothesley • Master Sexton • Henry VIII • Reginald Pole • Thomas Cranmer • Hugh Latimer • Norfolk - Tom Truth • William Fitzwilliam • Thomas Audley • Margaret Pole • Henry Pole • Richard Cromwell • Edward Seymour

This week’s theme: Murderous minds

After Anne’s head fell, Richard asked his uncle: ‘It is over, then?’ He replied: ‘Over? Oh no.’

Henry is ‘sincerely sorry, he will not do it again. And in this case perhaps he will not. The temptation to cut off your wife’s head does not arise every year.’ However, the queen’s death leaves a question hanging. Henry is king, but who will rule hereafter? Surely not ‘the ginger pig Eliza’. But then who?

This week is all about imagining royal deaths. For Henry’s children, it is not enough to know the evil stepmother is dead. ‘Tell me how she died,’ Mary asks. ‘She should have been burned alive.’ Richmond concurs: ‘I would have punished her more straitly.’

How? he wonders. What would have you done, sir? Hacked her head off with a rusty kitchen knife? Burned her with green wood?

Fitzroy goes further. He is sick, but his royal father is sicker still: his leg rots, and he will die. ‘When I am king,’ Richmond tells Cromwell, ‘I shall reward you.’

God help me, what are princes? They think on murder all day long. A patricide, now: as if the season does not hold enough surprises.

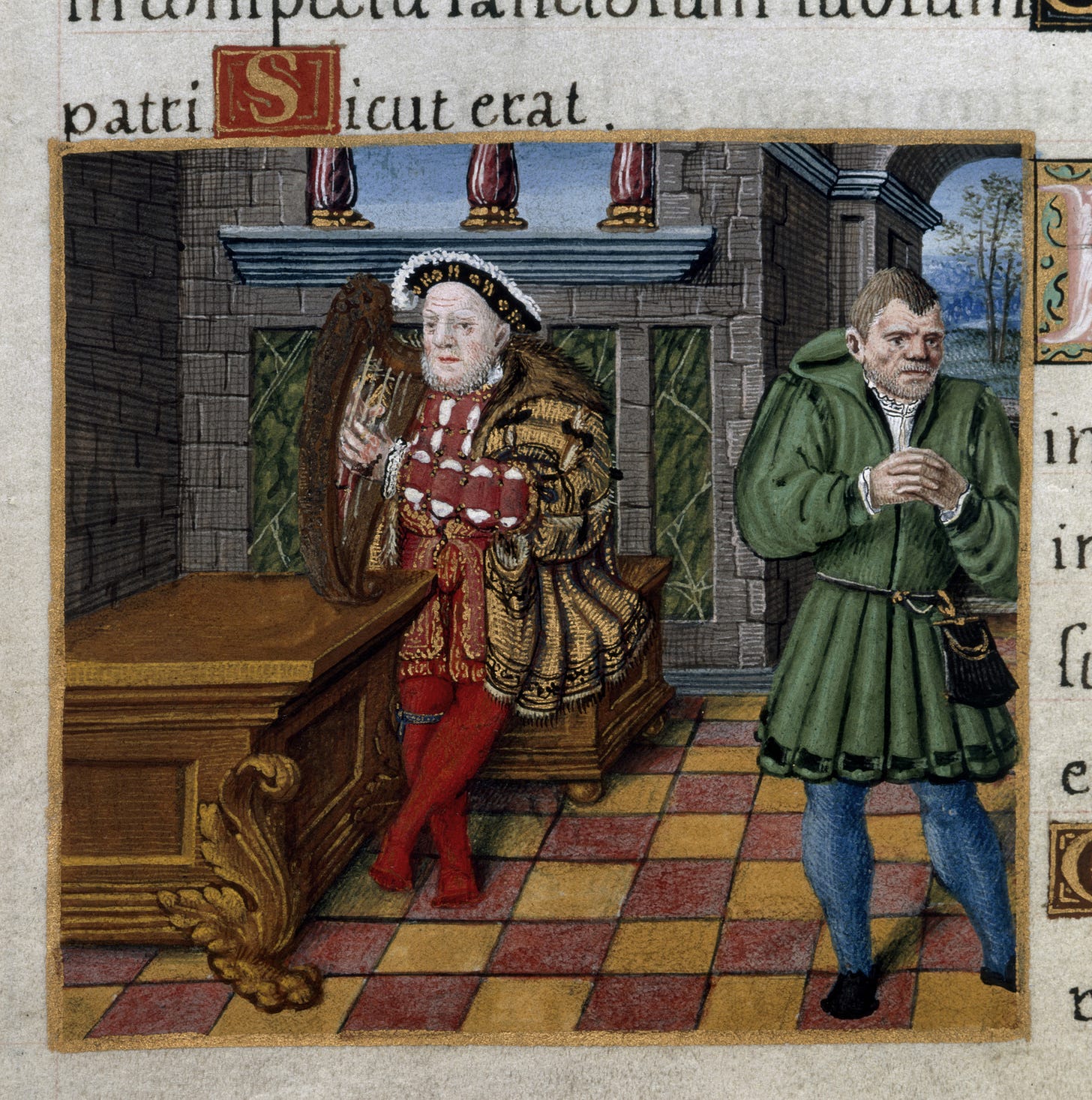

At the opening of Parliament, Richard Riche compares Henry to Absalom, the handsome son of King David. Gregory, student of stories, wonders whether the king will think he is being mocked. No one notes that Absalom fought his father and died a traitor’s death. No one but Cromwell recalls that Absalom had no sons to remember him by.1

Meanwhile, the king’s cousin Pole has written from across the sea. He damns Henry to hell, but hopes to scare him back to Rome. The king supposes Mary schemes against him to marry Reginald. He calls on the judges to bring her to trial. He asks Cromwell to take matters in hand. He means us to kill his daughter.

So, how are we to proceed? The future is a ‘curious blank’ where it is dangerous for our minds to go. ‘The Treason Act,’ says Margaret Pole. ‘I see its trip-wire. It is a crime to envisage the future.’ To imagine the king’s death.

‘We are trapped in the hour we occupy.’

At Austin Friars, Gregory says, ‘It’s not treason to say all men are mortal.’

'No, but it's not your best idea either.' He thinks, that was Anne Boleyn's mistake. She took Henry for a man like other men. Instead of what he is, and what all princes are: half god, half beast.'

So we need a better idea. How do you salvage the future from the wreckage of the past? How do you obey a king’s murderous mind, imprisoned in ‘his burdened and oppressed flesh’, and still staunch the blood and stop the rot?

Footnotes

1. Your journey to the underworld starts here

This week’s reading opens with Wyatt in the Tower reading Petrarch. Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, translated the Italian poet and introduced his metre and style into English, paving the way for Shakespeare’s sonnets later in the century.

Wyatt says:

‘In this edition the verses are arranged in an order that corresponds to the poet’s life. They tell a story. Or they seem to. I always want a story, don’t you?’

I can’t help but think that this is Mantel’s nod to the reader. Cromwell’s story is not linear. Time does appear to roll forward, but his past is full of gaps and half-rememberings. The Mirror and the Light has a story, but it requires the backstitch and the loop of thread lost beneath layers of cloth. To go forward we must go back.

Wyatt alludes to another Italian writer as he resigns himself to follow Cromwell:

‘I reach the crossroads and I throw the dice, and whichever comes up, it is the same – it is the swamp, or the abyss, or the ice. So I shall follow you as the gosling its mother. Or as Dante followed Virgil. Even to the underworld.’

This is not the first time Cromwell has been linked to the underworld. In Bring Up the Bodies, he was the glass-winged avenging angel from the cellars beneath the Vatican. Earlier in this chapter, the French ambassador asked him, ‘why do we lie and lie?’

‘And when we make our deathbed confession, will force of habit carry us to Hell?’

Now Reginald Pole is here, telling Henry he is damned. ‘Hell gapes for me,’ the king simmers. ‘Or so he says.’ Pole calls Cromwell a devil, pulling England down into the fires. His mother says, ‘You are a snake, Cromwell.’

'Oh no, no, no.' A dog, madam, and on your scent.

Wyatt’s father told of how a cat brought him a pigeon when Richard III had him locked in the Tower. ‘Prisoners believe all sorts of things,’ says his son. ‘A cat will come and save us. Thomas Cromwell will come with the key.’

He, Cromwell, Damacene cat, butcher’s dog, England’s devil… or our guide to the underworld in the court of Henry Tudor.

2. My master died of a broken heart

Wyatt says: ‘The Lord Cardinal was a great man for speed.’

He says: ‘He was a great man for everything.’

This week, Wolsey’s memory is invoked three times: by Wyatt, Richmond, and the fool Patch. They were all, like Cromwell, in the cardinal’s care and service. Patch mocked him, while Richmond remembered ‘a very splendid man.’

‘His end was not natural,’ says the king’s bastard. 'They tell me that his heart broke on the road, and that is what killed him.’ Cromwell recalls the day of Wolsey’s arrest, his hand on his ribs: ‘I have a pain… A pain as cold as a whetstone.’

If his heart broke, who broke it? No one but the king himself.

Master Sexton wonders why he is still alive, since all who harmed Wolsey are now ‘dead as you could require.’ But he, Cromwell, thinks only of Stephen Gardiner’s question: ‘what revenge will Thomas Cromwell seek on his sovereign, his prince?’

3. The future burns bright back into our present

For Hilary Mantel the future is no ‘curious blank.’ Historical fiction lends itself to dramatic irony because the readers are always better informed than the characters. The trick of the historical novelist is to take us into the half-lit dark of the historical present and forget the future has already happened.

But there are echoes from the future. Francis Bryan reports the thoughts of Cromwell’s nemesis, Stephen Gardiner:

‘He wonders why you are so fond of Katherine’s whelp. He claims you are protecting Mary, and it will undo you.’

When Mary ascends the throne in 1553, one of her first acts will be to release Stephen Gardiner from the Tower. He will return the favour by placing the crown on her head at her coronation. If Cromwell had not protected Mary in 1536, the new queen in 1553 may have been Anne’s whelp, Elizabeth. And Gardiner would have stayed locked up.

He, Cromwell, does not see this future. But he can smell Hugh Latimer’s fate:

Latimer smells of burning too. The air sparks around him as he walks.

Released from the Tower, Gardiner pursued Anne’s bishops, Thomas Cranmer and Hugh Latimer. Both were burned at the stake in Oxford, along with Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London. A memorial to the three ‘Oxford martyrs’ stands on Broad Street where they are believed to have died.

4. Ha! We are watching the past rewrite itself

‘We’re knocking down the HA-HAs, sir.’ The initials, he means, of Henry and the late queen: so fondly intertwined, like snakes breeding.

At the start of Bring Up the Bodies, builders were busy replacing Katherine’s pomegranates with Anne’s falcons. Now, the Seymour phoenix is rising, and all reminders of the Other One must go. They were not entirely successful.

sent me pictures of HA-HAs at Hampton Court, in lover’s knots like the one that slipped from Jane’s dress last week. Here is Bea’s own stitched HA-HA from her Book of Queens project:5. Cromwell’s Empire

'Thomas ...' the archbishop says. He pauses. His face mirrors an inner struggle. 'Thomas ... about the manor at Wimbeldon ... Since it pertains to your new title... you will want it, I suppose. At present it belongs to me – to the archdiocese, I should say.' 'And the house at Mortlake,' he says. 'If you would. The king will compensate you.'

Mortlake is upriver from Putney on the south bank of the Thames. Thomas Cranmer surrendered the Mortlake and Wimbledon manors to the king, possibly as recompense for his defence of Anne Boleyn. Henry then gifted these houses to his chief minister as a handsome reward for killing his wife.

Cromwell’s real estate empire is growing. He already owns his townhouse at Austin Friars, his country retreat at Stepney and his place of business at the Rolls House. Mortlake has a practical purpose: linking Cromwell’s estates to the king’s residences upriver at Richmond and Windsor. Symbolically, it ties him to his past. A stone's throw from Putney, it tells a story of how far he has come. And we always want a story, don’t we?

He, Lord Cromwell, is enthroned among them as Henry’s deputy, Vicegerent of the church under God and the king; where once, in Archbishop Morton’s day, he was the littlest and the lowest of the boys who scrubbed vegetables in the kitchen at Lambeth Palace.

Further reading:

6. Putting fools out of work

‘Lord Tom of Putney. You put the jesters out of occupation and make them beg a living. Let Somer watch himself. Who needs make a joke, when the jokes are walking and talking and calling themselves by the title of baron?’

William Somers is an interesting absence in the Cromwell trilogy. He is probably the most famous fool or jester at the Tudor court and we know he was very close to the king, who Will called ‘Harry’ and ‘Hal’. Mantel focuses on other fools: Anne’s dwarf who Norfolk kicks; Thomas More’s fool, Henry Patenson; and Cromwell’s own jester, Anthony.

And, of course, Patch. Like Mark Smeaton and Stephen Gardiner, he follows Cromwell’s journey from Wolsey’s service to the king’s court. Master Sexton links the story together and uses the fool’s prerogative to make fun of Master Secretary. Cromwell has a sense of humour, but he has no time for Patch, who committed the biggest sin in mocking the cardinal.

Further reading:

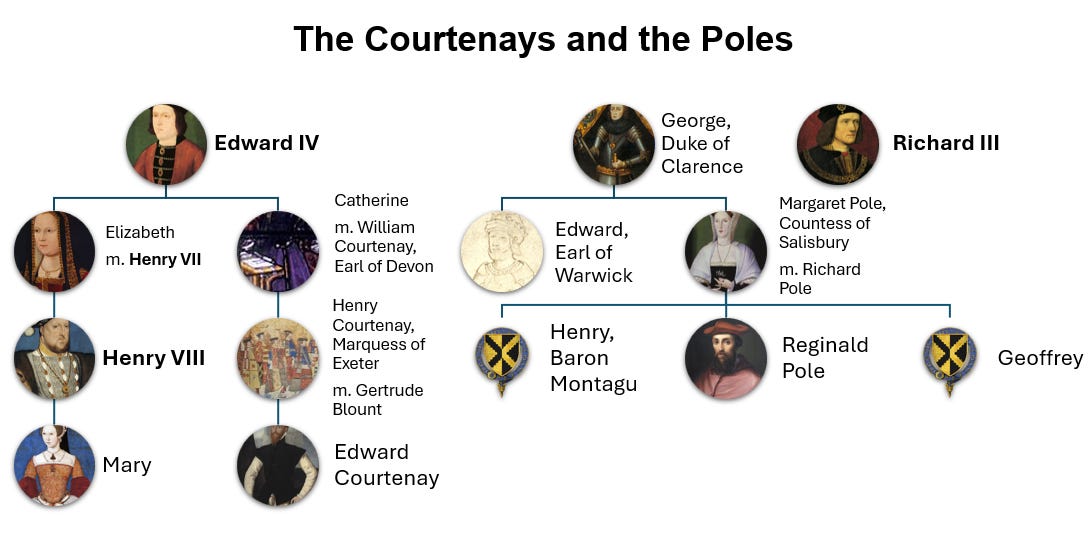

7. Old England dreams it will rule again

At the

in June, I had the pleasure of chairing a discussion on the role of the Poles and Courtenays in The Mirror and the Light. I was joined by Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch himself and the current Earl of Devon, Charles Courtenay. Charlie had, I kid you not, just come from a joust. His ancestors include Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter, who the king just banished from his council for being unable to control his wife, Gertrude. Charlie brought a lock of Gertrude’s hair, which you can see us examining here:

We will return to the Poles and Courtenays in more detail later. In brief, they are descended from the daughters of Edward IV and his brother, George. In 1485, their brother Richard III was defeated at Bosworth by Henry VIII’s father, heralding the start of the Tudor Age. But, ‘the Pole family and their allies dream of a new England: which is to say, an old one, where they rule again.’

Cromwell visits the Pole family at their townhouse, L’Erber. This house had been owned by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, also known as the Kingmaker for his influential role in the Wars of the Roses. Neville gave it to his daughter, who married George, Duke of Clarence, ancestor of the current Pole clan.

Margaret Pole appeared briefly in Wolf Hall during the Elizabeth Barton affair. Both her father and her brother died in the Tower, but Henry VIII restored their land and titles to Margaret and made her a countess in her own right. Henry only made two women peers of the realm. The other one just lost her head.

Cromwell says:

‘Who can read Margaret Pole, sir? Not I.’

The Plantagenet matriarch keeps her cards close to her chest. Five hundred years later, we may still wonder on her loyalty to the Tudor. Hilary Mantel wrote an excellent essay about how little we know about her, which I will link below.

Further reading:

The Haunting of Wolf Hall

For paying subscribers, more thoughts on the phantasmal in this week’s reading:

Quote of the week: His ink betrays him

In each novel, the king tasks Cromwell with destroying an obstruction in the royal design. Thomas More in Wolf Hall. Anne Boleyn in Bring Up the Bodies. In this third book, the king’s opponent is Reginald Pole. Unlike the previous two, he is permanently abroad, so we, Cromwell, never get to eyeball him properly. And unlike with More and Anne, we are unsuccessful in the king’s service. Pole survives and, as cardinal, returns to England under the reign of Mary to be her Archbishop of Canterbury, and England’s last Catholic archbishop.

However, thanks to Cromwell’s network of spies, we get to picture Pole in our mind’s eye:

Since then Reginald has been frightened of him. He speaks ill of him: says he is a devil, and you can't speak worse than that. And yet, when a travelling scholar calls on him, or a noble young Italian wishing to improve his English, Pole never thinks to ask, 'Could this be an emissary of Satan, alias Cromwell?' Time was, Reginald was tempted by Luther's teachings; we know how he wobbled onto that course, and wobbled off again. Time was, he doubted the Pope's authority; his doubts were recorded. Pole's folly is, that he thinks aloud. Some apprentice phrase, modelled on Cicero, trembles in the air; he believes no one hears. He writes, and he thinks no one reads; but friends of Lucifer look into his book. At dusk he locks his manuscript in a chest, but the devil has a key. Demons know every crossing-out and every blot. His ink betrays him. The fibres in his papers are spies. When he lies down at night, the horsehair in his mattress and the feathers in his bolster are eavesdropping on England's behalf, as he supplicates, in hedging, quibbling terms, whatever form of God he believes in that day.

Next week

Thank you for reading and joining me on this slow read of the Cromwell trilogy. Next week, we start the final section of ‘Salvage, London, Summer 1536’ This runs from pages 116 to 165 in the Fourth Estate paperback edition. It begins: ‘At the Tower, Francis Bryan says,’ It ends: ‘London, thou art the flower of cities all.’

And before I go, a quick reminder that this book group is entirely funded by its readers. So, if you have enjoyed this post and found it helpful, please consider a paid subscription to access the bonus episodes on The Haunting of Wolf Hall and start your own discussion threads in the chat area.

Alternatively, you can show your support with a one-off contribution by leaving me a tip over on Stripe. These always make my day and remind me that this project is worthwhile and finding a good home.

Until next week, I am your guide,

Master Simon Haisell

The real Richard Riche made these allusions, along with comparing Henry to the sun, driving away noxious vapours with his benevolent rays. Henry is indeed the light of England.

We have met Absalom before in Anne’s chamber, the day a candle set light to the tapestries, and almost fulfilled a prophecy that a queen of England will burn.

So many Henry jump scare here: '"I ask myself, what did /you/ know?" The king's eyes rest on him. "You do not seem amazed as I was amazed." It's the first overt distrust (that I remember) in the books and a dark note.

The scene with the council, too. One gets the distinct impression of being caught in a cage with the god/beast. I'm so happy nobody's offered me the position of advisor to a king, lol!

The fathers and the sons: The more I hear of Gregory, the more I like him.

While reading the paragraph where Cromwell thinks of fathers and sons, I had to think of Wolsey and Cromwell and their relationship at the end. How Wolsey so longed to see Cromwell during his last days and Cavendish had to lie to Wolsey, telling him that Cromwell will come and is just delayed. And before that, Cromwell stopped writing directly to Wolsey and communicated indirectly via his clerks to him. I know Cromwell tried to stay alive and did a lot for Wolsey, but...one last encounter would have meant so much for Wolsey on a personal level. I think he failed Wolsey there. That he is taking down everyone who was a enemy of Wolsey, is one motive and may sound better for him, but if he is honest, he is (foremost) taking out his enemies. So, end of my rant 😂