'Don't you mind? Don't you mind what we've done?' 'Perhaps I mind – but I know I'm part of it. Gabrielle, you see, she can't bear it – she thinks you've damned your soul and hers too. But for myself – I think possibly that when I first saw Camille, I was twelve then, twelve or thirteen – I thought, oh, here comes hell. It doesn't become me to start squealing now. Gabrielle married a nice young lawyer. I didn't.'

last week | main page | reading schedule | cast of characters | further resources

Hello and welcome to this slow read of A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. To get these posts in your inbox, turn on notifications for ‘2025 A Place of Greater Safety’ in your subscription settings.

This week, we are reading Part Five, Chapter I. Conspirators (1792).

Once you have read this week’s reading, you can explore this post and discuss in the comments. The reading schedule, cast of characters and further resources can be found here.

I start each post with a summary of the week’s story, followed by some background, footnotes and tangents.

And then it is over to you. In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

This week’s story

Georges Danton is now the Minister of Justice. Camille is his secretary, and delights in his father-in-law’s dismay, and relishes the thought of the news reaching Jean-Nicholas in Guise. Robespierre rejects Danton’s offer of a government job. They discuss what to do about the full prisons, and Max says the Girondins are traitors. Give me evidence, says Danton.

We consider the times we live in, the Revolution on steroids:

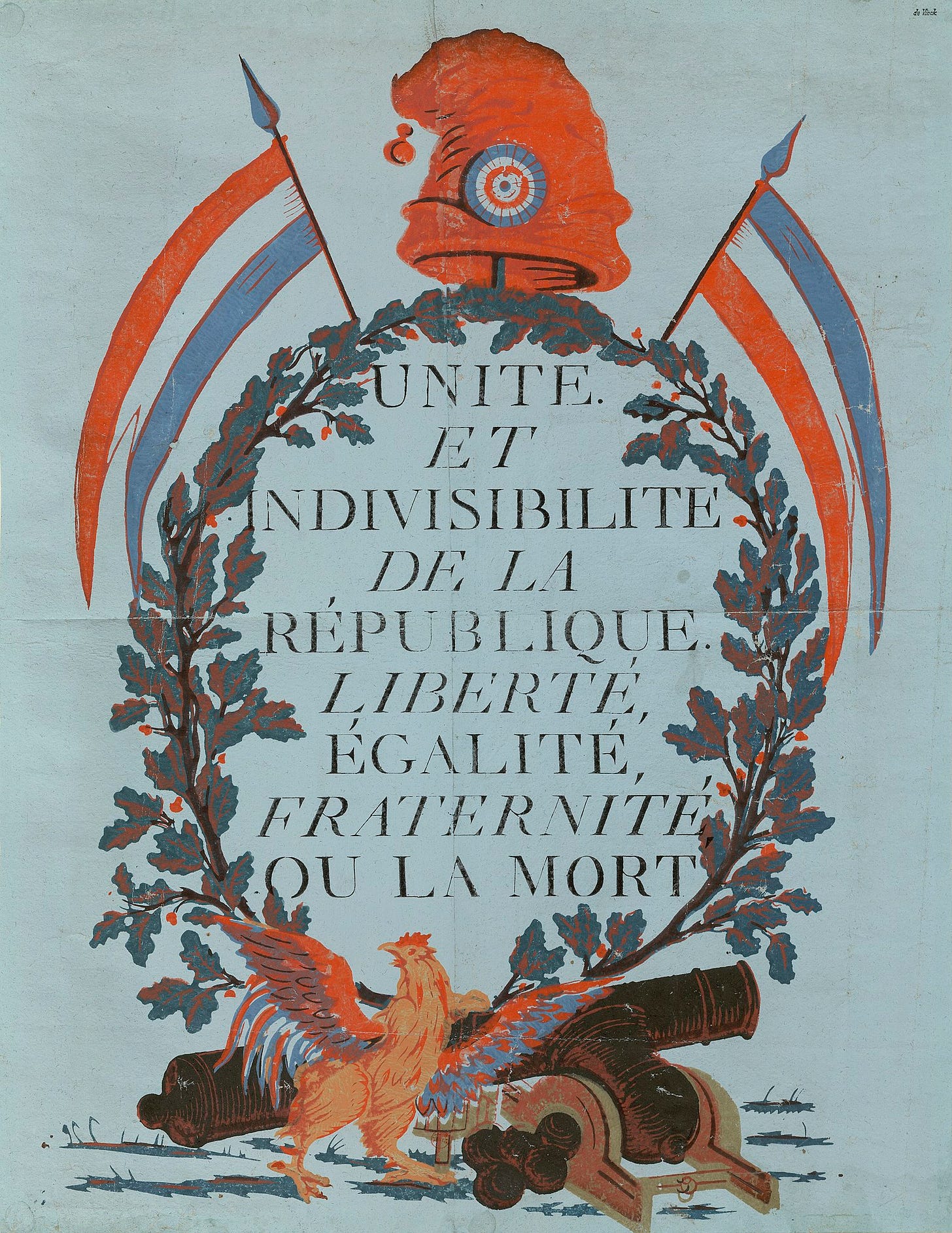

‘92, ‘93, ‘94. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death.

The Dantons move into the Place des Piques, so-named for the heads on spikes of revolutionary justice. All Danton’s mates get jobs. This, too, is justice. Lafayette is not Danton’s friend, and when news reaches the general, he deserts his post and falls into Austrian hands.

The Ministry of Justice has breakfast. The Minister plans “foreign business” with his neighbour, Lucile Desmoulins, but refuses to allow Fabre to bring his mistress to the Ministry. Meanwhile, the allies close in on Paris, and Jean-Marie Roland considers making a run for it. “I go nowhere,” says Danton.

Dr Marat comes to see Secretary Desmoulins with his plan for the prisoners: kill them. Camille says Danton will not like it. He doesn’t have to, says Marat. It is a necessity. On 1 September, Verdun falls. The enemy is two days from the capital. Robespierre broods about conspiracies, and Danton rallies Paris: “Dare, Always dare. And again, dare.”

Camille, Fabre, Marat and René Hébert scrutinise the prison lists and decide who to kill and who to save. Camille orders the release of his old principal, Father Bérardier, who married him to Lucile. The massacre begins. Danton’s official attitude: “I don’t know anything about this.”

Max goes to the Commune with warrants for the arrest of Brissot and Roland. Louvet takes them to Danton, who refuses to enact them. He goes to a horrified Gabrielle. In Camille’s rooms, he finds Lucile, who will not sleep with him – but does not seem to mind about murder.

Danton, Camille and Max are elected to the new National Convention. They sit with the old Duke of Orléans, styling himself now as Philippe Égalité. Fabre also joins the National Convention and reluctantly becomes Danton’s accomplice in a ruse to bribe the allied general, Brunswick, to lose a battle and save France.

“There’s another war on now. Either we kill Robespierre, or he will kill us.”

Background

If you are listening to Mike Duncan’s Revolutions podcast, then I recommend listening to:

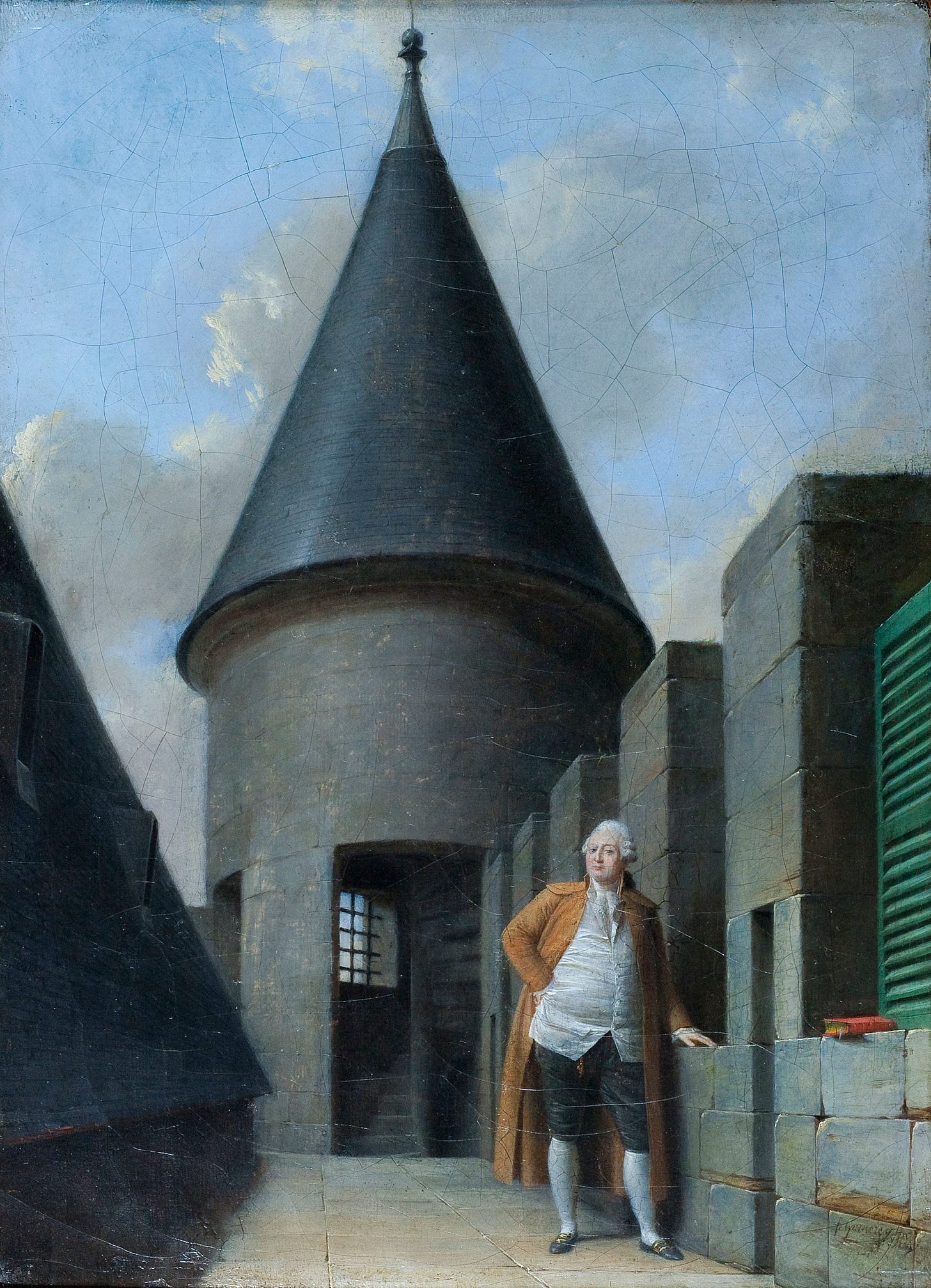

After the 10 August insurrection, the French monarchy is suspended, and elections begin for a National Convention to replace the constitution. The royal family are imprisoned, and Georges-Jacques Danton becomes Minister of Justice. Although the National Assembly continues to meet, power in Paris now lies in the Insurrectionary Commune led by Danton.

On the border, the war deteriorates further, and authorities in Paris call for the National Guard and volunteers to join the army and defend the capital. But as the men leave to fight, fears grow that counter-revolutionaries will take advantage of the situation.

Footnotes

1. Oedipal ghosts

Jean-Nicolas climbs the stairs. Camille (in ghost form) drifts up behind him. Jean-Nicolas has a letter in his hand. He peers at it; it is the familiar, semi-legible handwriting of his eldest son.

Later, the Genevan journalist Jacques Mallet du Pan will write that, “like Saturn, the Revolution devours its children.” Here, in 1792, one revolutionary is determined to haunt his parents. Camille wanted to sleep with Claude’s wife, but never got further than a kiss and the chaise longue. So he married their daughter and took over the government to wipe his boots on the desk:

‘I think I should like to collaborate on a violent and bloody revolution. Something that would give offence to my father.’

Every time he does something especially audacious in Paris, he makes sure to write home to Jean-Nicholas. The revolution delights in horrifying its parents. At the start of A Place of Greater Safety, Mantel quotes Rousseau, who says that the family is “the first model of political society. The head of the state bears the image of the father, the people, the image of his children.”

This is intergenerational warfare. Mantel asks, “What do we think about fathers? Important, or not?” They are worth writing about. The Wolf Hall trilogy explores Thomas Cromwell’s relationship with his real father, Walter and his surrogate father, Wolsey. Cromwell fosters a brood of sons, including the King of England, of whom some end up destroying him.

Mantel has written about her relationships with her father, Henry Thompson, and her stepfather, Jack Mantel. Her mother’s lover, Jack, moved into their house when Hilary was seven, and her father, Henry, remained with them in the house for the next four years. When they relocated, they left Henry behind, and Hilary took her stepfather’s name.

My father, might as well have been dead, except that the dead were more discussed. He was never mentioned after we parted: except by me, to me. We never met again.

2. The Templar curse and toy dogs

‘Yes, that’s the view of the Commune. It’s a bit grim for the children, after what they’ve been used to.’ Maximilien, Danton thought, were you once a child? ‘I’m told they’ll be made comfortable. They’ll be able to walk in the gardens. Perhaps the children would like to have a little dog they could take out?’

Marie Antoinette’s toy spaniel, Thisbe, accompanied the royal family into captivity. He had been a gift from Princess Marie-Thérèse de Lamballe, who is murdered in this chapter. According to some stories, Thisbe came with Marie Antoinette to the scaffold, and howled so much that he was killed for his pro-aristocratic sympathies.

On 13 August, the royal family were moved to the Temple, a medieval fortress built by the Knights Templar in the thirteenth century. The French crown had once been heavily in debt to the Templars. In 1307, Philip IV arrested the entire order and its Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, confiscating their property and charging them with heresy. On 18 March 1314, Molay was burned at the stake.

A story is told that Molay, dying on his pyre, cursed the French king to die within the year. Philip IV died that November, and four more kings died over the next fourteen years, leading to the collapse of the House of Capet. These events formed the basis of Maurice Druon’s historical novels, The Accursed Kings.

When Louis XVI was stripped of his title, he became Citizen Louis Capet, as the House of Bourbon was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty that began with Hugh Capet, King of the Franks, in 987. Louis Capet too is cursed and will be dead within the year.

3. The short road ahead

Life’s going to change. You thought it already had? Not nearly as much as it’s going to change now.

Mantel breaks the fourth wall again to tell the reader that “life’s going to change” now the Jacobins are in charge. This is a jarring flash-forward that gives us a glimpse of a complacently well-healed Camile Desmoulins in 1793 and Citizen Antoine Saint-Just in his high cravat on the Committee of Public Safety in the “dark and harrowing days of ‘94.”

It may only be September 1792, but time is getting on, and we will be dead two years from now.

‘92, ‘93, ‘94. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death.

4. An abattoir of a nation

‘Take your hands away from your face. Hypocrite. What do you think we did in ‘89? Murder mdae you. Murder took you out of the back streets and put you where you sit now. Murder! What is it? It’s a word.’

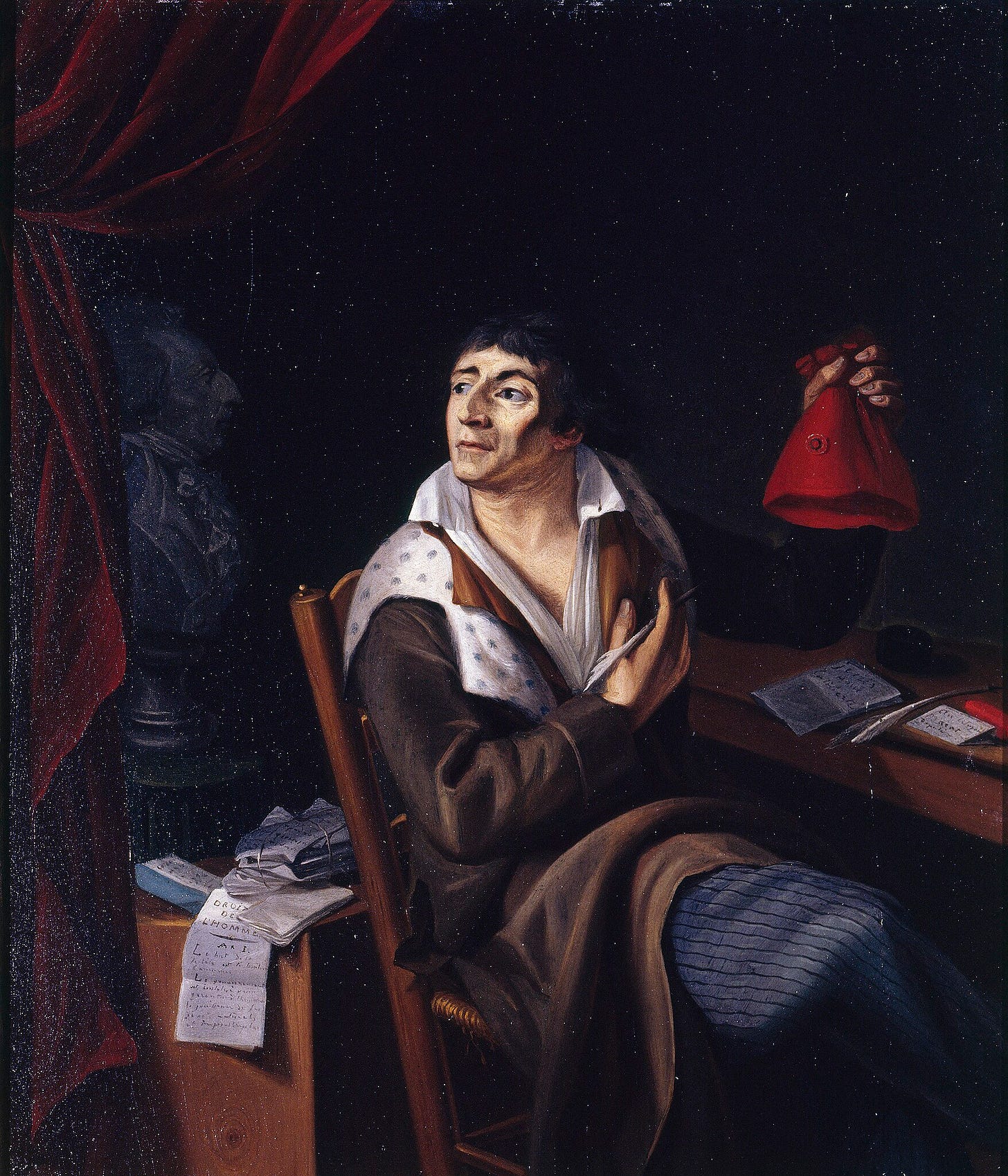

Before the 10 August insurrection, Jean-Paul Marat was a fairly marginal figure. He spent much of the period between July 1789 and August 1792 in hiding, including long periods avoiding arrest in the sewers and catacombs of Paris. His newspaper had a relatively small print run and readership, and in early 1792, he struggled to find the funds to sustain it.

After 10 August, everything changed for Marat. He was now a member of the Insurrectionary Paris Commune, and they secured for him four royal presses. His handbills were posted all over Paris:

…he was writing his opinions on wall-posters, and posting them up through the city. It was not a style to encourage subtlety, close argument; it made a man, he said, economical with his sympathies.

On 26 August, one of Marat’s posters appeared on every wall, demanding everyone mobilise to defeat the external and internal enemies of the Revolution: “from to-night on every armorer, cutler and locksmith must be ordered to engage in a public and unceasing manufacture of pikes and daggers.” It concluded:

In order to keep in check the enemies within, if will be sufficient to show them your daggers!

As we see in this chapter, Marat joins the newly formed Committee on Surveillance and is elected to the National Convention. Later this month, he will relaunch his newspaper as the Journal of the French Republic.

We are now living in the days of Jean-Paul Marat:

‘You and I, sunshine, are going to be shot.’

5. The conspirators within

These are the conspirators: why, he asked (since he is a reasonable man), does he fear conspiracy where no one else does? And answered, well, I fear what I have past cause to fear. And these are the conspirators within: the heart that flutters, the head that aches, the gut that won't digest, and eyes that, increasingly, cannot bear bright sunlight. Behind them is the master conspirator, the occult part of the mind; nightmares wake him at half-past four, and then there is nothing to do but lie in a hopeless parody of sleep until the day begins. To what end is this inner man conspiring? To take a night off and read a novel? To have more friends, to be liked a bit more? But people said, have you seen how Robespierre has taken to those tinted spectacles? It certainly gives him a sinister air.

Love this quote. Robespierre is our “reasonable man” driven to extreme paranoia. Even his own internal organs conspire against him.

Robespierre wore green-tinted spectacles to hide the “emotions of his inhuman soul”, according to one contemporary account. Perhaps it was just poor eyesight. Another account says people started calling him “the dragon”.

6. Daring Danton

Words make myths, it seems, and for their myths people fight to win.

Last week, I mentioned how Lenin held up Danton as an exemplary revolutionary. Lenin quoted Danton’s speech of 2 September, hours before the massacre began. The speech ends:

The tocsin which is about to sound is no alarm-signal but a summons to charge the foe. To conquer, gentlemen, we must dare, and dare, and dare, and so save France.

Like Marat’s posters, his “simple words” are designed to rally Paris against the invading Prusians and Austrians. But the Minister of Justice claims no responsibility for the hundreds of people killed over the next few days.

7. The massacres

‘The people are hungry and thirsty for justice.’

Between 2 and 6 September, 1,100–1,600 prisoners were killed in Paris, amounting to around half the prison population and all of the surviving Swiss Guard from the 10 August.

We will never, now, know an hour free from guilt; we will never, now, recover such reputation as we possessed; yet we neither planned nor willed the whole of it, the half of it. We simply turned away, we washed our hands, we made a list and we followed an agenda, we went home to sleep while the people did their worst and the people (Camille thinks) were translated from heroes to scavengers, to savages, to cannibals.

This week reminds me of the climax of Bring Up the Bodies, and Camille’s thoughts mirror those of Thomas Cromwell, who also recognises that this is a defining moment in his life. From heroes to cannibals, we will never be the same again.

8. Princesse de Lamballe

They put the head on a pike and hoisted it up to sway outside the high windows. ‘Come and say hallo to your friend,’ they exhorted the woman inside.

Marie Thérèse Louise of Savoy was a close friend and confidante of Marie Antoinette, having served as Superintendent of the Queen's Household. She was the target of slander and conspiracy theories, including the implication that her rooms at the Tuilleries were used for the shadowy “Austrian Committee” planning the counter-revolution.

Marie Thérèse was originally imprisoned with the royal family at the Temple, but on 19 August, she and two other noblewomen were relocated to La Force prison. On 3 September, she was brought before a tribunal and made to swear an oath to liberty and equality. She said she was happy to do so, but would not swear her hatred of the king and queen. According to the trial summary, the tribunal ordered, “Let Madame be set at liberty.”

As Mantel writes: “Freedom is the last thing they know.”

Danton to Pétion on Robespierre: “I bet he lives longer than we do.”

9. Secret Funds

‘When you add it all up,’ Camille pushed his hair back, ‘we’ve spent a lot of money over the past few weeks. It worries me to think that now we’re all deputies there’ll be new ministers soon, and they’ll want to know where the money has gone. Because really, I haven’t the least idea. I don’t suppose you have?’

This is just a heads-up that Danton, Camille and Fabre’s ministerial expenses will come back to haunt them before we’re done.

10. The Crown Jewels

‘You can’t afford to speak without thinking. No one must know the truth about his, not in a thousand years. The French are going to win a battle, that’s all. Your silence is the price of mine, and neither of us breaks the silence, even to save our own lives.’

In September 1792, over 10,000 precious stones were stolen from the royal household, including three diamonds called the "Regent", the "Sancy" and “the French Blue.” The first two diamonds were later recovered, but the whereabouts of the French Blue remained a mystery.

In 1812, an enormous blue diamond appeared in London, days after the expiry of a 20-year limit on legal proceedings. One theory suggests that the diamond reached King George IV through his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, the daughter of the allied general. Contemporaries linked the crown jewel theft and Brunswick’s unexplained defeat at the Battle of Valmy. It’s fairly far-fetched, but with so little evidence, Mantel is free to imagine it may have been true.

The diamond in London was later bought by the banker Thomas Hope and became known as the Hope Diamond. It was displayed at the Great Exhibition of London in 1851 and the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It is now held at the Smithsonian in the US.

In 2008, experts confirmed that the Hope Diamond was indeed cut from the French Blue once owned by the Sun King and stolen during the French Revolution. The diamond was formed 1.1 billion years ago and was extracted from the Kollur mine in Guntur, India, sometime before 1666.

There is a supposed curse linked to the diamond, and tragedy has befallen many of those who have worn it. One of its victims is said to be the Princess de Lamballe.

Thank you

Thank you for joining me on this slow read.

In the comments, let us know what caught your eye and ask the group any questions you may have. And if you’ve tumbled down a rabbit hole or taken your reading off on a tangent, please share where you have been and what you have found.

Next week, we will read Part Five, Chapter II. Robespirerricide & Chapter III. The Visible Exercise of Power

Until then, I wish everyone happy and adventurous reading.

Simon

Perhaps to keep me from dwelling on the extreme nastiness of this chapter, I found myself drawn to how Hilary describes Camille, and how she keeps us if not precisely on his side (where no-one of good sense would want to be, surely?), but at least wanting to hear from him again, see him again. He brightens the room. There’s the “Here comes hell” passage that Simon quotes at the start of his piece today—I don’t suppose Lucile actually said this (in French, I mean), but it’s so like her, and we know what she means. To be clear, I’m very far from being a romantic, and Camille is really not my type, but I know what Lucile means and I, we, know why she went for it, for him, the whole exciting and silly mess. I also like Danton picking up on Robespierre’s recommendation of Camille to do the government’s PR. Danton agrees: “Camille is good at versions.” Camille is so good at all sorts of things, except actually being good. (Doesn’t he say as much early on?)

And that extraordinary description of the Sea-Green Incorruptible: “Here Robespierre sat, very new, as if he had been taken out of a box and placed unruffled in a velvet armchair in Danton’s apartment.” It makes me think of a new toy, so precious that the child is not allowed to play with it: R’s honor is so precious, his conscience so tender, that he does not allow himself to do anything. Yet somehow he knows when anything happens, and always either has precise ideas as to what should happen next, or has made himself scarce. While it’s part of their attraction that neither Camille nor Lucile make excuses for themselves, Maximilian doesn’t *need* to make excuses for himself (not yet, anyway): he is careful to do nothing that needs to be excused.

I’ve found all the killing hard to read and kept looking for something to lighten the mood. I found it on pg 502 where the ‘cap of liberty’ is mentioned - “Why liberty is thought to require headgear is a mystery.” Made me smile😊 Thanks, Simon!